Alaska Seabird Information Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012

SCOTTISH NATURAL HERITAGE TREND NOTE Number 021, October 2012 SEABIRDS IN SCOTLAND Prepared by Simon Foster and Sue Marrs of SNH Knowledge Information Management Unit using results from the Seabird Monitoring Programme and the Joint Nature Conservation Committee Scotland has internationally important populations of several seabirds. Their conservation is assisted through a network of designated sites. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the 50 Special Protection Areas (SPA) which have seabirds listed as a feature of interest. The map shows the widespread nature of the sites and the predominance of important seabird areas on the Northern Isles (Orkney and Shetland), where some of our largest seabird colonies are present. The most recent estimate of seabird populations was obtained from Birds of Scotland (Forrester et al., 2007). Table 1 shows the population levels for all seabirds regularly breeding in Scotland. Table 1: Population Estimates for Breeding Seabirds in Scotland. Figure 1: Special Protection Areas for Seabirds Breeding in Scotland. Species* Unit** Estimate Key Points Northern fulmar 486,000 AOS Manx shearwater 126,545 AOS Trends are described for 11 of the 24 European storm-petrel 31,570+ AOS species of seabirds breeding in Leach’s storm-petrel 48,057 AOS Scotland Northern gannet 182,511 AOS Great cormorant c. 3,600 AON Nine have shown sustained declines European shag 21,500-30,000 PAIRS over the past 20 years. Two have Arctic skua 2,100 AOT remained stable. Great skua 9,650 AOT The reasons for the declines are Black headed -

High-Resolution Numerical Modeling of Near-Surface Weather Conditions Over Alaska’S Cook Inlet and Shelikof Strait

High-Resolution Numerical Modeling of Near-Surface Weather Conditions over Alaska’s Cook Inlet and Shelikof Strait Peter Q. Olsson Principal Investigator Co-principal Investigators: Haibo Liu Final Report OCS Study MMS 2007-043 October 2009 This study was funded in part by the U.S. Department of the Interior, Minerals Management Service (MMS) through Cooperative Agreement No. M08AR12675, between MMS, Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Region, and the University of Alaska Fairbanks. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. High-Resolution Numerical Modeling of Near-Surface Weather Conditions over Alaska’s Cook Inlet and Shelikof Strait Peter Q. Olsson Principal Investigator Co-principal Investigators: Haibo Liu Final Report OCS Study MMS 2007-043 October 2009 Contact information Coastal Marine Institute School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences University of Alaska Fairbanks P. O. Box 757220 Fairbanks, AK 99775-7220 email: [email protected] phone: 907.474.7208 fax: 907.474.7204 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables...................................................................................................................................ii List of Figures..................................................................................................................................ii Abstract...........................................................................................................................................1 -

OGC-98-5 U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Committee on GAO Resources, House of Representatives November 1997 U.S. INSULAR AREAS Application of the U.S. Constitution GAO/OGC-98-5 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 Office of the General Counsel B-271897 November 7, 1997 The Honorable Don Young Chairman Committee on Resources House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: More than 4 million U.S. citizens and nationals live in insular areas1 under the jurisdiction of the United States. The Territorial Clause of the Constitution authorizes the Congress to “make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property” of the United States.2 Relying on the Territorial Clause, the Congress has enacted legislation making some provisions of the Constitution explicitly applicable in the insular areas. In addition to this congressional action, courts from time to time have ruled on the application of constitutional provisions to one or more of the insular areas. You asked us to update our 1991 report to you on the applicability of provisions of the Constitution to five insular areas: Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (the CNMI), American Samoa, and Guam. You asked specifically about significant judicial and legislative developments concerning the political or tax status of these areas, as well as court decisions since our earlier report involving the applicability of constitutional provisions to these areas. We have included this information in appendix I. 1As we did in our 1991 report on this issue, Applicability of Relevant Provisions of the U.S. -

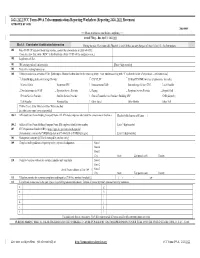

2021 2022 FCC Form 499-A Telecommunications Reporting

2021 2022 FCC Form 499-A Telecommunications Reporting Worksheet (Reporting 2020 2021 Revenues) APPROVED BY OMB 3060-0855 >>> Please read instructions before completing.<<< Annual Filing -- due April 1, 20212022 Block 1: Contributor Identification Information During the year, filers must refile Blocks 1, 2 and 6 if there are any changes in Lines 104 or 112. See Instructions. 101 Filer 499 ID [If you don't know your number, contact the administrator at (888) 641-8722. If you are a new filer, write “NEW” in this block and a Filer 499 ID will be assigned to you.] 102 Legal name of filer 103 IRS employer identification number [Enter 9 digit number] 104 Name filer is doing business as 105 Telecommunications activities of filer [Select up to 5 boxes that best describe the reporting entity. Enter numbers starting with “1” to show the order of importance -- see instructions.] Audio Bridging (teleconferencing) Provider CAP/CLEC Cellular/PCS/SMR (wireless telephony inc. by resale) Coaxial Cable Incumbent LEC Interconnected VoIP Interexchange Carrier (IXC) Local Reseller Non-Interconnected VoIP Operator Service Provider Paging Payphone Service Provider Prepaid Card Private Service Provider Satellite Service Provider Shared-Tenant Service Provider / Building LEC SMR (dispatch) Toll Reseller Wireless Data Other Local Other Mobile Other Toll If Other Local, Other Mobile or Other Toll is checked describe carrier type / services provided: 106.1 Affiliated Filers Name/Holding Company Name (All affiliated companies must show the same -

Breeding Status and Population Trends of Seabirds in Alaska, 2014

BREEDING STATUS AND POPULATION TRENDS OF SEABIRDS IN ALASKA, 2014 U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE AMNWR 2015/03 BREEDING STATUS AND POPULATION TRENDS OF SEABIRDS IN ALASKA, 2014 Compiled By: Donald E. Dragoo, Heather M. Renner and David B. Ironsa Key words: Aethia, Alaska, Aleutian Islands, ancient murrelet, Bering Sea, black-legged kittiwake, Cepphus, Cerorhinca, Chukchi Sea, common murre, crested auklet, fork-tailed storm-petrel, Fratercula, Fulmarus, glaucous-winged gull, Gulf of Alaska, hatching chronology, horned puffin, Larus, Leach’s storm-petrel, least auklet, long-term monitoring, northern fulmar, Oceanodroma, parakeet auklet, pelagic cormorant, Phalacrocorax, pigeon guillemot, Prince William Sound, productivity, red-faced cormorant, red-legged kittiwake, rhinoceros auklet, Rissa, seabirds, Synthliboramphus, thick-billed murre, tufted puffin, Uria, whiskered auklet. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge 95 Sterling Highway, Suite 1 Homer, Alaska, USA 99603 February 2015 Cite as: Dragoo, D. E., H. M. Renner, and D. B. Irons. 2015. Breeding status and population trends of seabirds in Alaska, 2014. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Report AMNWR 2015/03. Homer, Alaska. aDragoo ([email protected]) and Renner ([email protected]), Alaska Maritime NWR, Homer; Irons ([email protected]), U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Migratory Bird Management, 1011 East Tudor Road, Anchorage, Alaska USA 99503 When using information from this report, data, results, or conclusions specific to a location(s) should not be used in other publications without first obtaining permission from the original contributor(s). Results and conclusions general to large geographic areas may be cited without permission. This report updates previous reports. -

Breeding Ecology and Extinction of the Great Auk (Pinguinus Impennis): Anecdotal Evidence and Conjectures

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VOL. 101 JANUARY1984 No. 1 BREEDING ECOLOGY AND EXTINCTION OF THE GREAT AUK (PINGUINUS IMPENNIS): ANECDOTAL EVIDENCE AND CONJECTURES SVEN-AXEL BENGTSON Museumof Zoology,University of Lund,Helgonavi•en 3, S-223 62 Lund,Sweden The Garefowl, or Great Auk (Pinguinusimpen- Thus, the sad history of this grand, flightless nis)(Frontispiece), met its final fate in 1844 (or auk has received considerable attention and has shortly thereafter), before anyone versed in often been told. Still, the final episodeof the natural history had endeavoured to study the epilogue deservesto be repeated.Probably al- living bird in the field. In fact, no naturalist ready before the beginning of the 19th centu- ever reported having met with a Great Auk in ry, the GreatAuk wasgone on the westernside its natural environment, although specimens of the Atlantic, and in Europe it was on the were occasionallykept in captivity for short verge of extinction. The last few pairs were periods of time. For instance, the Danish nat- known to breed on some isolated skerries and uralist Ole Worm (Worm 1655) obtained a live rocks off the southwesternpeninsula of Ice- bird from the Faroe Islands and observed it for land. One day between 2 and 5 June 1844, a several months, and Fleming (1824) had the party of Icelanderslanded on Eldey, a stackof opportunity to study a Great Auk that had been volcanic tuff with precipitouscliffs and a flat caught on the island of St. Kilda, Outer Heb- top, now harbouring one of the largestsgan- rides, in 1821. nettles in the world. -

Resource Utilization in Atka, Aleutian Islands, Alaska

RESOURCEUTILIZATION IN ATKA, ALEUTIAN ISLANDS, ALASKA Douglas W. Veltre, Ph.D. and Mary J. Veltre, B.A. Technical Paper Number 88 Prepared for State of Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Subsistence Contract 83-0496 December 1983 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS To the people of Atka, who have shared so much with us over the years, go our sincere thanks for making this report possible. A number of individuals gave generously of their time and knowledge, and the Atx^am Corporation and the Atka Village Council, who assisted us in many ways, deserve particular appreciation. Mr. Moses Dirks, an Aleut language specialist from Atka, kindly helped us with Atkan Aleut terminology and place names, and these contributions are noted throughout this report. Finally, thanks go to Dr. Linda Ellanna, Deputy Director of the Division of Subsistence, for her support for this project, and to her and other individuals who offered valuable comments on an earlier draft of this report. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . e . a . ii Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION . e . 1 Purpose ........................ Research objectives .................. Research methods Discussion of rese~r~h*m~t~odoio~y .................... Organization of the report .............. 2 THE NATURAL SETTING . 10 Introduction ........... 10 Location, geog;aih;,' &d*&oio&’ ........... 10 Climate ........................ 16 Flora ......................... 22 Terrestrial fauna ................... 22 Marine fauna ..................... 23 Birds ......................... 31 Conclusions ...................... 32 3 LITERATURE REVIEW AND HISTORY OF RESEARCH ON ATKA . e . 37 Introduction ..................... 37 Netsvetov .............. ......... 37 Jochelson and HrdliEka ................ 38 Bank ....................... 39 Bergslind . 40 Veltre and'Vll;r;! .................................... 41 Taniisif. ....................... 41 Bilingual materials .................. 41 Conclusions ...................... 42 iii 4 OVERVIEW OF ALEUT RESOURCE UTILIZATION . 43 Introduction ............ -

Biological Monitoring at Aiktak Island, Alaska in 2016

AMNWR 2017/02 BIOLOGICAL MONITORING AT AIKTAK ISLAND, ALASKA IN 2016 Sarah M. Youngren, Daniel C. Rapp, and Nora A. Rojek Key words: Aiktak Island, Alaska, Aleutian Islands, ancient murrelet, Cepphus columba, common murre, double-crested cormorant, fork-tailed storm-petrel, Fratercula cirrhata, Fratercula corniculata, glaucous-winged gull, horned puffin, Larus glaucescens, Leach’s storm-petrel, Oceanodroma furcata, Oceanodroma leucorhoa, pelagic cormorant, Phalacrocorax auritus, Phalacrocorax pelagicus, Phalacrocorax urile, pigeon guillemot, population trends, productivity, red-faced cormorant, Synthliboramphus antiquus, thick-billed murre, tufted puffin, Uria aalge, Uria lomvia. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge 95 Sterling Highway, Suite 1 Homer, AK 99603 January 2017 Cite as: Youngren, S. M., D. C. Rapp, and N. A. Rojek. 2017. Biological monitoring at Aiktak Island, Alaska in 2016. U.S. Fish and Wildl. Serv. Rep., AMNWR 2017/02. Homer, Alaska. Tufted puffins flying along the southern coast of Aiktak Island, Alaska. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 1 STUDY AREA ............................................................................................................................................... 1 METHODS ................................................................................................................................................... -

Sea of Okhotsk: Seals, Seabirds and a Legacy of Sorrow

SEA OF OKHOTSK: SEALS, SEABIRDS AND A LEGACY OF SORROW Little known outside of Russia and seldom visited by westerners, Russia's Sea of Okhotsk dominates the Northwest Pacific. Bounded to the north and west by the Russian continent and the Kamchatka Peninsula to the east, with the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin Island guarding the southern border, it is almost landlocked. Its coasts were once home to a number of groups of indigenous people: the Nivkhi, Oroki, Even and Itelmen. Their name for this sea simply translates as something like the ‘Sea of Hunters' or ‘Hunters Sea', perhaps a clue to the abundance of wildlife found here. In 1725, and again in 1733, the Russian explorer Vitus Bering launched two expeditions from the town of Okhotsk on the western shores of this sea in order to explore the eastern coasts of the Russian Empire. For a long time this town was the gateway to Kamchatka and beyond. The modern make it an inhospitable place. However the lure of a rich fishery town of Okhotsk is built near the site of the old town, and little and, more recently, oil and gas discoveries means this sea is has changed over the centuries. Inhabitants now have an air still being exploited, so nothing has changed. In 1854, no fewer service, but their lives are still dominated by the sea. Perhaps than 160 American and British whaling ships were there hunting no other sea in the world has witnessed as much human whales. Despite this seemingly relentless exploitation the suffering and misery as the Sea of Okhotsk. -

Introduction

AMNWR 08/13 BIOLOGICAL MONITORING AT AIKTAK ISLAND, ALASKA IN 2008: SUMMARY APPENDICES Brie A. Drummond Key words: Aiktak Island, Alaska, Aleutian Islands, ancient murrelet, Cepphus columba, common murre, double-crested cormorant, fork-tailed storm-petrel, Fratercula cirrhata, Fratercula corniculata, glaucous-winged gull, horned puffin, Larus glaucescens, Leach’s storm-petrel, Oceanodroma leucorhoa, Oceanodroma furcata, pelagic cormorant, Phalacrocorax auritus, Phalacrocorax pelagicus, Phalacrocorax urile, pigeon guillemot, population trends, productivity, red-faced cormorant, Synthliboramphus antiquus, thick-billed murre, tufted puffin, Uria aalge, Uria lomvia U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Aleutian Islands Unit 95 Sterling Hwy, Suite 1 Homer, Alaska 99603 September 2008 Cite as: Drummond, B. A. Biological monitoring at Aiktak Island, Alaska in 2008: summary appendices. U.S. Fish and Wildl. Serv. Rep., AMNWR 08/13. Homer, Alaska. 139 pp. Southern coast of Aiktak Island, Alaska, in early June. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................................... 1 STUDY AREA............................................................................................................................................. ..1 METHODS.................................................................................................................................................. ..2 INTERESTING OBSERVATIONS.............................................................................................................. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

1••I Haras São Miguel

r L 1 :1 .4 1••I HARAS SÃO MIGUEL CAMPINAS - S. P. Proprietário: SR. ANTONIO ALVES DE MORAES 5/ 1 Pharos Nearo N.,ara Nasrulla h Blenhes m Mumtaz Begun Mumtaz Mahal [ CAMPANHA Truculentr Flag of Truce Respite I Conco dia A campanha dos 2 anos de Capitain Kidd foi bastante D,ophon expressiva, tendo vencido o "Stechworth Stakes" e o importante 1 Orama Cantelupe "National Breeders Procluce Stakes" (lb. 6.623) e colocando-se em 2.0 no "Gimcrack Stakes". CAPITUN KI1)D II Alazão - Inglaterra 1956 Aos 3 anos correu os "2.000 Guineus", tendo se colocado em Phalaris lugar, sendo depois vendido para os U.S.A. Prosseguindo sua Falrway Scapa Flow 5.0 campanha nesse Pais, ganhou 7 corridas, entre elas o "Fort Lau- Stephan the Great Blue Peter derdale Handicap" (sôbre Polylad e Petare. 1 milha e 1/16 em Fancy Free Celiba 102 s. e o "Broaclway Handicap" (Aqueduct. 1 milha e 1/16 em Hurry On J Marcovil 102. 8 a.) e colocando-se no "I{ollywood Premiere Handicap" Jy 1 Tout Suíte (Hollywood Park, ganho por Fleet Nasrullah) e no "Coronado Juniata í Junior Handicap" (Hollywood Park), totalizando USS 44.190. Samphre ALGUMAS REPRODUTORAS IMPORTADAS Branding IÂLY IRON LA PAT'l'I Enchanted Forest V.T(HF/R SuperlorI1 Solonaway BI( BÂMB()() CANI)ELl1'.' (.-1RN()R\I [ (IRCÊ 1 Selim Hassan 1)rPI'ElI Grie FIRF CHO' 4 Tucior Castle Citronade Desajiada 1 Foolish Falrel Propriedade de Revista Turf e Fomento Ltda. órgão Oficial das Comissões de Fomento e Turf do Jockey Club de São Paulo IniCliatíva ) Redator Responsável ANTERO DE CASTRO Já se disse que o Posto de Fomento Agropecuário do Jockey Club de São Paulo teria o seu lado negativo, repre- sentado pelo arrefecimento da iniciativa particular no setor das importações, çue provocaria como conseqüência de ofe- recer aos criadores os serviços de garanhões de primeira categoria.