OGC-98-5 U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project Leader Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge

Project Leader Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge Location Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and Battle of Midway National Memorial is located 1,300 miles from the main Hawaiian Islands and is part of the Northwestern Hawaiian Island chain. In addition to being a refuge and national memorial, Midway Atoll is also a part of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, one of the largest protected areas in the world. Midway Atoll is recognized as globally important for breeding albatross and other seabirds, and for its historic and cultural significance. It is also home to Henderson Field, an FAA emergency stop airport for transpacific flights. The island is inhabited year round by a population of ~50 residents that are a mix of FWS employees, volunteers, interns, and contractors of various nationalities. It is a tight, close-knit community where residents work, live, and spend down time together. Skills/Specialized Experience The Project Leader position at Midway Atoll NWR is one of the most unique and challenging refuge management positions in the refuge system. The ideal candidate would have experience working in remote locations, managing a large and diverse group of people, and possess an ability to maintain calm and steady leadership in the face of unexpected challenges. We are looking for a leader who will prioritize the safety, security and wellness of the island residents above all else. Other exciting challenges include complicated logistics as all supplies and personnel must be flown or shipped to the island, working with a variety of partners who rely on the island for staging (Coast Guard), monitoring (NOAA, DOD, etc...) and mission critical amenities (FAA and airport), and managing an airfield, a robust biological program, and the logistics of supporting a remote community. -

5. Ecological Impacts of the 2015/16 El Niño in the Central Equatorial Pacific

5. ECOLOGICAL IMPACTS OF THE 2015/16 EL NIÑO IN THE CENTRAL EQUATORIAL PACIFIC RUSSELL E. BRAINARD, THOMAS OLIVER, MICHAEL J. MCPHADEN, ANNE COHEN, ROBErtO VENEGAS, ADEL HEENAN, BERNARDO VARGAS-ÁNGEL, RANDI ROtjAN, SANGEETA MANGUBHAI, ELIZABETH FLINT, AND SUSAN A. HUNTER Coral reef and seabird communities in the central equatorial Pacific were disrupted by record-setting sea surface temperatures, linked to an anthropogenically forced trend, during the 2015/16 El Niño. Introduction. In the equatorial Pacific Ocean, the El Niño were likely unprecedented and unlikely to El Niño–Southern Oscillation substantially affects have occurred naturally, thereby reflecting an anthro- atmospheric and oceanic conditions on interannual pogenically forced trend. Lee and McPhaden (2010) time scales. The central and eastern equatorial earlier reported increasing amplitudes of El Niño Pacific fluctuates between anomalously warm and events in Niño-4 that is also evident in our study nutrient-poor El Niño and anomalously cool and region (Figs. 5.1b,c). nutrient-rich La Niña conditions (Chavez et al. 1999; Remote islands in the CEP (Fig. 5.1a), including Jar- McPhaden et al. 2006; Gierach et al. 2012). El Niño vis Island (0°22′S, 160°01′W), Howland Island (0°48′N, events are characterized by an eastward expansion of 176°37′W), Baker Island (0°12′N, 176°29′W), and the Indo-Pacific warm pool (IPWP) and deepening Kanton Island (2°50′S, 171°40′W), support healthy, of the thermocline and nutricline in response resilient coral reef ecosystems characterized by excep- to weakening trade winds (Strutton and Chavez tionally high biomass of planktivorous and piscivorous 2000; Turk et al. -

Listing of Eligible Units of Local Government

Eligible Units of Local Government The 426 counties and cities/towns listed below had a population of more than 200,000 people in 2019 according to the Census Bureau. The name of the county or city/town is the name as it appears in the Census Bureau’s City and Town Population Subcounty Resident Population Estimates file. The list below was created using the Census Bureau’s City and Town Population Subcounty Resident Population Estimates file from the 2019 Vintage.1 The data are limited to active governments providing primary general-purpose functions and active governments that are partially consolidated with another government but with separate officials providing primary general-purpose functions.2 The list below also excludes Census summary level entities that are minor civil division place parts or county place parts as these entities are duplicative of incorporated and minor civil division places listed below. State Unit of local government with population that exceeds 200,000 Alabama Baldwin County Alabama Birmingham city Alabama Huntsville city Alabama Jefferson County Alabama Madison County Alabama Mobile County Alabama Montgomery County Alabama Shelby County Alabama Tuscaloosa County Alaska Anchorage municipality Arizona Chandler city Arizona Gilbert town Arizona Glendale city Arizona Maricopa County Arizona Mesa city Arizona Mohave County 1 The Census data file is available at https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/datasets/2010- 2019/cities/totals/sub-est2019_all.csv and was accessed on 12/30/2020. Documentation for the data file can be found at https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/technical-documentation/file-layouts/2010-2019/sub- est2019.pdf. -

My County Works Activity Book

My County Works A County Government Activity Book Dear Educators and Parents, The National Association of Counties, in partnership with iCivics, is proud to present “My County Works,” a county government activity book for children. It is designed to introduce students to counties’ vast responsibilities and the important role counties play in our lives every day. Counties are one of America’s oldest forms of government, dating back to 1634 when the first county governments (known as shires) were established in Virginia. The organization and structure of today’s 3,069 county governments are chartered under state constitutions or laws and are tailored to fit the needs and characteristics of states and local areas. No two counties are exactly the same. In Alaska, counties are called boroughs; in Louisiana, they’re known as parishes. But in every state, county governments are on the front lines of serving the public and helping our communities thrive. We hope that this activity book can bring to life the leadership and fundamental duties of county government. We encourage students, parents and educators to invite your county officials to participate first-hand in these lessons–to discuss specifically how your county works. It’s never too early for children to start learning about civics and how they can help make our communities better places to live, work and play. Please visit www.naco.org for more information about why counties matter and our efforts to advance healthy, vibrant, safe counties across the United States. Matthew Chase Executive Director National Association of Counties Partnering with iCivics The National Association of Counties and iCivics have developed a collection of civic education resources to help young people learn about county government. -

5 (Lql"~ (T~I ~ Fl'u<Y

~-----" (t~i ~ fl'U<y 5 (lql"~ MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT AMONG THE STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES AND THE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE AND THE u.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION NATIONAL OCEAN SERVICE AND NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE FOR PROMOTING COORDINATED MANAGEMENT IN THE NORTHWESTERN HAWAIIAN ISLANDS University Of Hawaii School of Law Library - Jon Van Dyke Archives Collection I. BACKGROUND A. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) include a vast and remote chain of islands that are a part of the Hawaiian archipelago and provide habitat to numerous species found nowhere else on earth. These islands represent a nearly pristine ecosystem where habitats upon which marine species depend include both land and water. This area represents the majority of the coral reefs found in the United States' jurisdiction and supports more than 7,000 marine species, of which half are unique to the Hawaiian Islands chain. The area is rich in history and represents a place ofciilturaI-sfgnificahcelotheHtlativeHawaiians:lt is an-area that must be carefully managed to ensure that the resources are not diminished for future generations. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are also the most remote archipelago in the world. This isolation has resulted in need for integrated resource management of this vast and exceptional marine environment. There is a need for coordinated management in this unique and special pl~ce where various State and Federal agencies and advisory councils have a variety of authorities and jurisdiction. B. The area subject to this Agreement is the lands and waters of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands out to 50 nautical miles and includes all atolls, reefs, shoals, banks, and islands from Nihoa Island in the Southeast to Kure Atoll in the Northwest. -

Agroforestry: Enhancing Resiliency in U.S

Southeast and Caribbean Sarah Workman, Becky Barlow, and John Fike Sarah Workman is the associate director of the Highlands Biological Station, University of North Carolina; Becky Barlow is an associate professor, School of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences, Auburn University; John Fike is an associate professor, College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Virginia Tech. Description of the Region (fig. A.15). All of these land uses provide significant produc- tivity and income. The Southeast encompasses physiographic Cropland and pastureland occupy significant portions of land provinces, or ecoregions (Wear and Greis 2012), that have area in the Southeastern United States. Forests occupy from 50 unique climate, fire history, and composition of vegetation. to 69 percent of the land within each State in the region From the physiographic province of the Appalachian Mountains Figure A.15. Acres of landuse categories of the 11 Southeastern States. (Map and table prepared by William M. Christie, Eastern Forest Environmental Threat Assessment Center, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Asheville, NC). Agroforestry: Enhancing Resiliency in U.S. Agricultural Landscapes Under Changing Conditions 189 to the alluvial plains of the Mis sissippi River Basin, within land use outside developed zones is perhaps best viewed in deciduous forests of Kentucky and Tennessee and the Interior terms of the nature of woody plant cover and whether animals Highlands of the Ozarks, to the Piedmont, Flatwoods, and are excluded or allowed access. Both Puerto Rico and the U.S. Coastal Plains, a large portion of the land area is appropriate Virgin Islands are experiencing a trend toward an increase in for implementing several types of agroforestry, integrating woody cover with the loss of agricultural land and pastureland either crops or livestock, or both, with trees and woody (Brandeis and Turner 2013a, 2013b; Brandeis et al. -

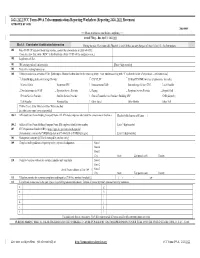

2021 2022 FCC Form 499-A Telecommunications Reporting

2021 2022 FCC Form 499-A Telecommunications Reporting Worksheet (Reporting 2020 2021 Revenues) APPROVED BY OMB 3060-0855 >>> Please read instructions before completing.<<< Annual Filing -- due April 1, 20212022 Block 1: Contributor Identification Information During the year, filers must refile Blocks 1, 2 and 6 if there are any changes in Lines 104 or 112. See Instructions. 101 Filer 499 ID [If you don't know your number, contact the administrator at (888) 641-8722. If you are a new filer, write “NEW” in this block and a Filer 499 ID will be assigned to you.] 102 Legal name of filer 103 IRS employer identification number [Enter 9 digit number] 104 Name filer is doing business as 105 Telecommunications activities of filer [Select up to 5 boxes that best describe the reporting entity. Enter numbers starting with “1” to show the order of importance -- see instructions.] Audio Bridging (teleconferencing) Provider CAP/CLEC Cellular/PCS/SMR (wireless telephony inc. by resale) Coaxial Cable Incumbent LEC Interconnected VoIP Interexchange Carrier (IXC) Local Reseller Non-Interconnected VoIP Operator Service Provider Paging Payphone Service Provider Prepaid Card Private Service Provider Satellite Service Provider Shared-Tenant Service Provider / Building LEC SMR (dispatch) Toll Reseller Wireless Data Other Local Other Mobile Other Toll If Other Local, Other Mobile or Other Toll is checked describe carrier type / services provided: 106.1 Affiliated Filers Name/Holding Company Name (All affiliated companies must show the same -

Northern Mariana Islands

NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS CUSTOMS REGULATIONS AND INFORMATION FOR IMPORTS HOUSEHOLD GOODS AND PERSONAL EFFECTS Note: American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI), the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Baker Island, Howland Islands, Jarvis Island, Johnston Island, Kingman Reef, Midway Islands, Palmyra, and Wake Island are all territories / possessions of the United States and as such are subject to the importation rules of the United States. They may have additional requirements to import into each territory as each one has a delicate ecosystem they are trying to protect. An individual is generally considered a bona fide resident of a territory / possession if he or she is physically present in the territory for 183 days during the taxable year, does not have a tax home outside the territory during the tax year, and does not have a closer connection to the U.S. or a foreign country. However, U.S. citizens and resident aliens are permitted certain exceptions to the 183-day rule. Documents Required Copy of Passport (some ports require Passports for all family members listed on the 3299) Form CF-3299 Supplemental Declaration (required by most ports) Detailed inventory in English Copy of Visa (if non-US citizen / permanent resident) / copy of Permanent Resident Card I-94 Stamp / Card Copy of Bill of Lading (OBL) / Air Waybill (AWB) Form DS-1504 (Diplomats) A-1 Visa (Diplomats) Importers Security Filing (ISF) Specific Information The shipper must be present during Customs clearance. All shipments are subject to inspection. Do not indicate “packed by owner” (PBO) or miscellaneous descriptions on the detailed inventory. -

Veterinarian Shortage Situation Nomination Form

Shortage ID VMLRP USE ONLY NIFA Veterinary Medicine National Institute of Food and Agriculture Loan Repayment Program (VMLRP) US Department of Agriculture Form NIFA 2009‐0001 OMB Control No. 0524‐0050 Veterinarian Shortage Situation Expiration Date: 9/30/2019 Nomination Form To be submitted under the authority of the chief State or Insular Area Animal Health Official Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program (VMLRP) This form must be used for Nomination of Veterinarian Shortage Situations to the Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program (VMLRP), Authorized Under the National Veterinary Medical Service Act (NVMSA) Note: Please submit one separate nomination form for each shortage situation. See the State Animal Health Official (SAHO) section of the VMLRP web site (www.nifa.usda.gov/vmlrp) for the number of nominations permitted for your state or insular area. Location of Veterinary Shortage Area for this Nomination Location of Veterinary Shortage: (e.g., County, State/Insular Area; must be a logistically feasible veterinary practice service area) Approximate Center of Shortage Area (or Location of Position if Type III): (e.g., Address or Cross Street, Town/City, and Zip Code) Overall Priority of Shortage: ______________ Type of Veterinary Practice Area/Discipline/Specialty (select one) : ________________________________________________________________________________ For Type I or II Private Practice: Must cover(check at least one) May cover Beef Cattle Beef Cattle Dairy Cattle Dairy Cattle Swine Swine Poultry Poultry Small -

B: Other U.S. Island Possessions in the Tropical Pacific

Appendix B Other U.S. Island Possessions in the Tropical Pacific1 Introduction Howland, Jarvis, and Baker Islands There are eight isolated and unincorporated is- Howland, Jarvis and Baker are arid coral islands lands and reefs under U.S. control and sovereignty in the southern Line Island group (figure B-l). Aside in the tropical Pacific Basin. Included in this cate- from American Samoa, Jarvis Island is the only gory are: Kingman Reef, Palmyra and Johnston other U.S.-affiliated island in the Southern Hemi- Atolls in the northern Line Island group; Howland, sphere. These islands lie within one-half degree Baker and Jarvis Islands in the southern Line Is- from the equator, in the equatorial climatic zone. land group; Midway Atoll at the northwest end of During the 19th century the United States and the Hawaiian archipelago; and Wake Island north Britain actively exploited the significant guano de- of the Marshall Islands. Evidence indicates that posits found on these three islands. Jarvis Island some of these islands were not inhabited prior to was claimed by the United States in 1857, and sub- “Western” discovery; and today some remain unin- sequently annexed by Britain in 1889. Jarvis, Howland, habited. and Baker Islands were made territories of the These islands range from less than 1 degree south United States in 1936, and placed under the juris- latitude to nearly 29 degrees north latitude and from diction of the Department of the Interior. The is- 162 degrees west to 167 east longitude. The climate lands currently are uninhabited. regimes range from arid to wet and equatorial to These atolls were used as weather stations and subtropical. -

Veterinarian Shortage Situation Nomination Form

4IPSUBHF*% AK163 7.-3164&0/-: NIFAVeterinaryMedicine NationalInstituteofFoodandAgriculture LoanRepaymentProgram(VMLRP) USDepartmentofAgriculture FormNIFA2009Ͳ0001 OMBControlNo.0524Ͳ0046 VeterinarianShortageSituation ExpirationDate:11/30/2016 NominationForm Tobesubmitted undertheauthorityofthechiefStateorInsularAreaAnimalHealthOfficial VeterinaryMedicineLoanRepaymentProgram(VMLRP) ThisformmustbeusedforNominationofVeterinarianShortageSituationstotheVeterinaryMedicineLoanRepaymentProgram (VMLRP),AuthorizedUndertheNationalVeterinaryMedicalServiceAct(NVMSA) Note:Pleasesubmitoneseparatenominationformforeachshortagesituation.SeetheStateAnimalHealthOfficial(SAHO)sectionof theVMLRPwebsite(www.nifa.usda.gov/vmlrp)forthenumberofnominationspermittedforyourstateorinsulararea. LocationofVeterinaryShortageAreaforthisNomination Kenai Peninsula, Alaska LocationofVeterinaryShortage: (e.g.,County,State/InsularArea;mustbealogisticallyfeasibleveterinarypracticeservicearea) ApproximateCenterofShortageArea Kenai or Soldotna: area extends from Portage (just south of Anchorage down to (orLocationofPositionifTypeIII): Homer at the tip of the Kenai Peninsula) (e.g.,AddressorCrossStreet,Town/City,andZipCode) OverallPriorityofShortage: @@@@@@@@@@@@@@Critical Priority TypeofVeterinaryPracticeArea/Discipline/Specialty;ƐĞůĞĐƚŽŶĞͿ͗ @@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@Type II: Private Practice - Rural Area, Food Animal Medicine (awardee obligation: at least 30%@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ FTE or 12hr/week) &ŽƌdLJƉĞ/Žƌ//WƌŝǀĂƚĞWƌĂĐƚŝĐĞ͗ Musƚcover(checkĂtleastone) -

MINERAL INVESTIGATIONS in SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA by A. F

MINERAL INVESTIGATIONS IN SOUTHEASTERN ALASKA By A. F. BUDDINGTON INTRODUCTION In the Sitka district the continued operation of the Chicagoff and Hirst-Chicagof gold mines and the installation and operation of a new mill at the Apex-El Nido property in 1924, all on Chichagof Island, have stimulated a renewed interest in prospecting for gold ores. In the Juneau district a belt of metamorphic rock, which extends from Funter Bay to Hawk Inlet on Admiralty Island and con tains a great number of large, well-defined quartz fissure veins, was being prospected on the properties of the Admiralty-Alaska Gold Mining Co. and the Alaska-Dano Co. on Funter Bay and of Charles Williams and others on Hawk Inlet. The Admiralty-Alaska Co. Avas driving a long tunnel which is designed to cut at depth several large quartz veins. On the Charles Williams property a long shoot of ore has been proved on one vein and a large quantity of quartz that assays low in gold. In the Wrangell district the only property being prospected dur ing 1924 to an extent greater tihan that required for assessment work was the silver-lead vein on the Lake claims, east of Wrangell. In the Ketchikan district, as reported, the Dunton gold mine, near Hollis, was operated during 1924 by the Kasaan Gold Co. and the Salt Chuck palladium-copper mine by the Alaskan Palladium Co., and development work on a copper prospect was being carried on at Lake Bay. In the Hyder district the outstanding feature for 1924 has been the development of ore shoots at the Riverside property to the stage which has been deemed sufficient to warrant construction of a 50-ton mill to treat the ore by a combination of tables and flotation.