Recent Decisions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Download a PDF of an Interview with Frédéric De Narp, President and Chief

A Brilliant Beginning An Interview with Frédéric de Narp, President and Chief Executive Offi cer, Harry Winston, Inc. EDITORS’ NOTE Frédéric de Narp currently have eight salons. our next visits harry winston. we are currently working assumed his current post at Harry largest market is in Japan, but the rest on a new salon concept that will celebrate the Winston in January of 2010. Prior of the world is yet to be developed for tradition and aesthetics of harry winston in a to this, he served as the President harry winston. we have plans to fur- warmer and more welcoming environment. this and CEO of Cartier North America. ther develop in europe where we see fall, we will unveil two new salons under this He began his career in luxury re- some strong potential. over the next concept: a Las vegas salon and our renovated tail nearly 20 years ago at Cartier in few years, we will also look to expand fl agship salon on Fifth avenue, designed with ar- Japan, and worked in various po- our presence in and around china, chitect, william sofi eld, who just won the cooper sitions with the company in Tokyo, where the brand continues to perform hewitt national design award. Switzerland, Italy, and Greece be- well. harry winston currently has a The brand has been focused on giving fore moving to New York in 2005 to network of 20 retail salons worldwide, back from the beginning. How critical is oversee Cartier North America. so there is tremendous opportunity for that to the culture of Harry Winston, and Frédéric de Narp the brand to grow, while remaining how important is it going forward to main- COMPANY BRIEF Harry Winston exclusive. -

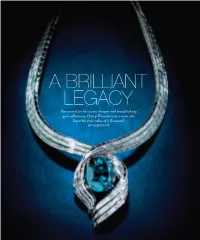

Renowned for His Iconic Designs and Breathtaking Gem Collections, Harry Winston Was a Man Who Knew the True Value of a Diamond

A BRILLIANT LEGACY Renowned for his iconic designs and breathtaking gem collections, Harry Winston was a man who knew the true value of a diamond. BY ALLISON HATA 54 A diamond is anything but just another stone. Highly coveted, precious and exceedingly rare, diamonds can take on different meanings: a symbol of status, a statement of love or a sign of purity. “Diamonds are a physical connection to [the earth] other than our feet on the ground,” says Russell Shor, a senior industry analyst for the Gemologist Institute of America. “When the earth was young and there was volcanic mass seething inside—this is how diamonds were formed. Diamonds connect us to that.” One man understood this intrinsic connection and dedicated his life to bringing the world closer to the precious gem through his jewelry designs and generous gifts to national institu- tions. Known as the “king of dia- monds,” the late Harry Winston was the first American jeweler to own and cut some of the most iconic stones in history, in addi- tion to setting a new standard for jewelry that showcases a gem’s natural beauty. Born more than a century ago, the young Winston—the son of a small jewelry shop owner—demonstrated a natural instinct for examining diamonds and precious gems. In subsequent years, he cultivated this talent to become one of the most prominent diamond merchants and designers of his time. His legacy lives on through the house of Harry Winston, which pairs his classic vision with a contemporary sensi- bility to create modern pieces that still grace the red carpet today. -

Star of the South: a Historic 128 Ct Diamond

STAR OF THE SOUTH: A HISTORIC 128 CT DIAMOND By Christopher P. Smith and George Bosshart The Star of the South is one of the world’s most famous diamonds. Discovered in 1853, it became the first Brazilian diamond to receive international acclaim. This article presents the first complete gemological characterization of this historic 128.48 ct diamond. The clarity grade was deter- mined to be VS2 and the color grade, Fancy Light pinkish brown. Overall, the gemological and spectroscopic characteristics of this nominal type IIa diamond—including graining and strain pat- terns, UV-Vis-NIR and mid- to near-infrared absorption spectra, and Raman photolumines- cence—are consistent with those of other natural type IIa diamonds of similar color. arely do gemological laboratories have the from approximately 1730 to 1870, during which opportunity to perform and publish a full ana- time Brazil was the world’s principal source of dia- Rlytical study of historic diamonds or colored mond. This era ended with the discovery of more stones. However, such was the case recently when significant quantities of diamonds in South Africa. the Gübelin Gem Lab was given the chance to ana- According to Levinson (1998), it has been esti- lyze the Star of the South diamond (figure 1). This mated that prior to the Brazilian finds only about remarkable diamond is not only of historical signifi- 2,000–5,000 carats of diamonds arrived in Europe cance, but it is also of known provenance—cut from annually from the mines of India. In contrast, the a piece of rough found in the state of Minas Gerais, Brazilian finds supplied an estimated 25,000 to Brazil, almost 150 years ago. -

Estate Jewelry Their Signed Work Consistently Fetches a Premium—Sometimes up to Three Times the ESTATE JEWELRY Only Reliable Source

HOW TO BUY Most estate dealers insist that the finest pieces never go on display. In addition JAR workshop at Place Vendôme turns out heirloom pieces that regularly earn two to Deco-era Cartier, the market is perpetually starved for natural (as opposed to cul- to three times their estimates at auction. Other designers to watch include Munich- tured) pearls and über-rare gemstones: Kashmir sapphires, “pigeon’s blood” Burmese based Hemmerle and New York’s Taffin, by James de Givenchy, a nephew of the cel- rubies from the fabled tracts of Mogok, Golconda diamonds. Most of the mines that ebrated couturier Hubert de Givenchy. produce these treasured gems have long since closed, making estate jewelry their Signed work consistently fetches a premium—sometimes up to three times the ESTATE JEWELRY only reliable source. value of a similar but unsigned piece. Greg Kwiat, the new CEO of Fred Leighton, says BY VICTORIA GOMELSKY “We have about a half-dozen people we call” when something special turns up, he recently inspected an important 1930s diamond necklace by Van Cleef & Arpels: says Walter McTeigue, co-founder of high-end jeweler McTeigue & McClelland, citing “On the strength of that signature, we increased our offer by 50 percent.” The provenance of a major piece of jewelry can often add to its allure and its retail value. an oil-shipping magnate, a publish- Add a well-documented prove- ing heiress, and a star hedge-fund M.S. Rau Antiques nance to the mix, and all bets are off. manager as clients who make his Jacques-Charles “A Cartier bandeau that was once But be sure you get the story straight before you hand over the cash Mongenot Louis XVI short list. -

Calm Down NEW YORK — East Met West at Tiffany on Sunday Morning in a Smart, Chic Collection by Behnaz Sarafpour

WINSTON MINES GROWTH/10 GUCCI’S GIANNINI TALKS TEAM/22 WWDWomen’s Wear Daily • The Retailers’MONDAY Daily Newspaper • September 13, 2004 • $2.00 Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear Calm Down NEW YORK — East met West at Tiffany on Sunday morning in a smart, chic collection by Behnaz Sarafpour. And in the midst of the cross-cultural current inspired by the designer’s recent trip to Japan, she gave ample play to the new calm percolating through fashion, one likely to gain momentum as the season progresses. Here, Sarafpour’s sleek dress secured with an obi sash. For more on the season, see pages 12 to 18. Hip-Hop’s Rising Heat: As Firms Chase Deals, Is Rocawear in Play? By Lauren DeCarlo NEW YORK — The bling-bling world of hip- hop is clearly more than a flash in the pan, with more conglomerates than ever eager to get a piece of it. The latest brand J.Lo Plans Show for Sweetface, Sells $15,000 Of Fragrance at Macy’s Appearance. Page 2. said to be entertaining suitors is none other than one that helped pioneer the sector: Rocawear. Sources said Rocawear may be ready to consider offers for a sale of the company, which is said to generate more than $125 million in wholesale volume. See Rocawear, Page4 PHOTO BY GEORGE CHINSEE PHOTO BY 2 WWD, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 13, 2004 WWW.WWD.COM WWDMONDAY J.Lo Talks Scents, Shows at Macy’s Accessories/Innerwear/Legwear By Julie Naughton and Pete Born FASHION The spring collections kicked into high gear over the weekend with shows Jennifer Lopez in Jennifer Lopez in from Behnaz Sarafpour, DKNY, Baby Phat and Zac Posen. -

Jewellery Collectors

Diamonds Diamond collectors The most mesmerising rock of them all, the diamond, transcends fashion, era and cultures, with new-age and yesteryear celebrities alike coming back for more and more f course, collecting is Beyoncé’s blast at the 2014 a game won by those who Grammys followed Carrie Ohave been at it the longest, Underwood rocking a $31 million but hot on the diamond-encrusted necklace designed by Jonathan heels of luminaries Queen Elizabeth Arndt the year before. II, Elizabeth Taylor and Madonna South Africa is a world leader are Lady Gaga, Beyoncé and in diamond mining and Charlize Charlize Theron. Theron is never afraid to fly her Lady Gaga is regularly lighting flag. She made a statement at the up red carpets in one way or 2014 Academy Awards with another, but the $30m Tiffany & a 21-carat emerald-cut stone Harry Co. 128.54-carat Tiffany Yellow Winston necklace that she paired Diamond necklace she wore at with diamond earrings for a total the 2019 Academy Awards was of $15.8m worth on Hollywood’s perfectly aligned to her A Star is biggest night. Born reincarnation. It was, in fact, Other notable sparklers the very necklace Audrey Hepburn include Cate Blanchett who wore wore when she promoted Breakfast $18m-worth of Chopard diamonds at Tiffany’s. Just a month before, at the 2014 Academy Awards, Gaga had dazzled at the Golden including opal earrings, a diamond Globes with a Tiffany & Co. bracelet and a pear-shaped necklace featuring a 20-carat pear- diamond ring. shaped center stone accompanied Look no further than the classic by 300 other diamonds and a fashionistas to see where these hot price tag of $5m. -

D Lesson 14.Pdf

The Mystique of Diamonds The Diamond Course Diamond Council of America © 2015 The Mystique of Diamonds In This Lesson: • Magic and Romance • Nature’s Inspirations • Adding to the Spell • Diamonds and Time • Diamond Occasions • Diamond Personalities MAGIC AND ROMANCE In most diamond presentations, it’s important to cover the 4Cs. A little information about topics such as formation, sources, mining, or cutting can often help, too. In every pre- sentation, however, it’s essential to identify and reinforce the factors that make diamonds valuable and important – in other words, truly precious – to each customer. After all, purchase decisions involve the head, but the desire to own or give a diamond almost always springs from the heart. That’s the realm of magic and romance. The emotional meanings of diamonds have many origins and they have evolved over thou- sands of years. Diamond’s unique beauty and remarkable properties have helped create some of the deepest meanings. Others have come from cultural traditions, the glamour of celebrities, and the events of individual lives. In a sales presentation, you need to The desire to own or give diamond determine which of these elements will resonate for the cus- jewelry springs from the heart, not from the head. tomer you’re serving. Photo courtesy Andrew Meyer Jewelry. The Diamond Course 14 Diamond Council of America © 1 The Mystique of Diamonds It’s important to remember that people most often buy diamonds to symbolize love or to celebrate personal mile- stones. Sometimes the motivation for buying is obvious – for example, with an engagement ring. -

Record Setters Rarity, Provenance and Authenticity, Along with Global Economic Conditions, Are Driving Record Prices at Auction

Record Setters Rarity, provenance and authenticity, along with global economic conditions, are driving record prices at auction. BY Ettagale Blauer February 2012 It seems record-breaking prices have become the norm at every major jewelry auction, but a look back shows that the highest prices paid for certain gems and jewels were set more than 20 years ago. That these records have held up is all the more remarkable considering the tremendous increase in appreciation for rare and fine, unique gems and jewels in recent years. The potential audience for these treasures is dramatically more global than it was barely a quarter-century ago. This is partly due to the sophisticated and aggressive marketing by the top auction houses, but also to the new wealth being amassed in parts of the world that were not even on the radar until recently. Stir in a limited number of available pieces and records are bound to be set. While rarity, provenance and authenticity are the usual hallmarks behind record-setting results, economic conditions can play just as big a role. The Night of the Iguana Brooch, sold at Christie’s Elizabeth A rush to hard goods, considered a safer haven Taylor auction. Diamond-set beast was described as a dolphin by its designer, Jean Schlumberger for than cash, has been evident in the current global Tiffany & Co. It was given to Taylor by Richard Burton for the turmoil. These new collectors have become premiere of the film of the same name on August 11, 1964. highly sophisticated consumers of gems and Photo courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd. -

Fine Jewelry

FINE JEWELRY HA.COM/JEWELRY FINE JEWELRY Offering a wide selection of expertly catalogued fine jewelry to the world’s ostm discerning collectors, Heritage Auctions’ Fine Jewelry department specializes in Contemporary, Vintage and Estate Jewelry, along with designer pieces from exclusive brands such as Cartier, Tiffany and Harry Winston. Diamond, Emerald, White Gold Brooch, Cartier Sold For: $21,250 HA.com/Jewelry | [email protected] 1 SELECT HALL OF FAME Kashmir Sapphire, Diamond, Diamond, White Gold Ring Colombian Emerald, Diamond, Platinum Ring Sold For: $425,000 Platinum Ring Sold For: $527,500 Sold For: $302,500 Fancy Light Yellow Diamond, Fancy Yellow Diamond, Diamond, Gold Ring Diamond, Platinum, Gold Ring Sold for: $324,500 Sold for: $365,000 Colombian Emerald, Diamond, Gold Ring, Unmounted Emerald-cut Diamond, Kashmir Sapphire, Diamond, Kurt Wayne Type IIa, 9.26 carats Platinum Ring Sold for: $100,000 Sold For: $902,500 Sold for: $670,000 2 HA.com/Jewelry | [email protected] CONSIGNMENT DECISION Whether you’re consigning an entire collection or a single valuable piece, we are happy to assess, answer your questions, and aid in curating your precious goods. From estimating and researching your pieces to presenting them to the right buyers, we create an approach focused on the Fine Jewelry market to garner the highest results possible. • Heritage Auctions has presented more than 8,500+ successful auctions, selling more than $10 billion since 1976 • More than 308,000+ individual consignments have been sold successfully, with full, timely payment to every consignor • 72,938 bidders have used HERITAGE Live!®1, winning more than 1,042,918 lots valued well in excess of $1.5 billion in recent years 1. -

VINTAGE JEWELS & DIAMONDS SPARKLE at CHRISTIE's LONDON in JUNE • Exceptional Diamonds • Jewellery from the Collection

For Immediate Release Friday, 11 April 2008 Contact: Hannah Schmidt +44 (0) 207 389 2964 [email protected] Alexandra Kindermann + 44 (0) 207 389 2289 [email protected] VINTAGE JEWELS & DIAMONDS SPARKLE AT CHRISTIE’S LONDON IN JUNE • Exceptional Diamonds • Jewellery from the Collection of Christina Onassis (1950-1987) Jewels: The London Sale Christie’s London 11 June 2008 at 11am London – A spectacular selection of diamonds and Jewellery from the Collection of Christina Onassis (1950-1987) highlight Christie’s Jewels: The London Sale on 11 June 2008. Featuring 230 beautiful rings, bracelets, necklaces, pearls, single stones together with pieces from some of the most sought-after jewellers including Cartier, Chaumet, Harry Winston and Van Cleef & Arpels, estimates range from £2,000 to £2,200,000. The sale is expected to realise in excess of £8 million. DIAMONDS Amongst the spectacular selection of diamonds is a beautiful crossover ring by Graff with a fancy vivid yellow pear-shaped diamond of 4.15 carats, internally flawless clarity contrasting with the pear-shaped diamond of 4.79 carats, E colour and VVS1 clarity (estimate: £100,000-120,000), illustrated left. More colour is provided by a 7.12 carats cushion-shaped fancy light greenish-blue diamond ring (estimate: £180,000-220,000) and a 30.81 fancy yellow diamond (estimate: £250,000-350,000). Colourless diamonds are well represented by one of the largest, most exceptional 19th century diamond rivieres to be offered at auction in many years, with 55 collets ranging from 1 carat to 10 carats (estimate:£400,000-500,000), an impressive 15.02 carats heart-shaped diamond pendant (estimate: £600,000-800,000) and a pair of ear pendants, the pear-shaped drops weighing 5.89 and 5.84 carats (estimate: £100,000-150,000), illustrated right. -

Magnificent Jewels

PRESS RELEASE | NEW Y O R K | 23 MARCH 202 1 | F O R IMMEDIATE RELEASE CHRISTIE'S NEW YORK MAGNIFICENT JEWELS LIVE AUCTION: 13 APRIL 2021 ONLINE AUCTION: 8-20 APRIL 2021 ‘THE PERFECT PALETTE’ Fancy Vivid Blue Diamond Ring of 2.13 carats $2,000,000-3,000,000 Fancy Vivid Orange Diamond Ring of 2.34 carats $1,500,000-2,500,000 Fancy Vivid Purplish Pink Diamond Ring of 2.17 carats $1,500,000-2,500,000 New York – Christie’s New York announces the April 13 auction of Magnificent Jewels and the concurrent Jewels Online sale from April 8-20. The auction includes a significant selection of colorless diamonds, colored diamonds, and gemstones, along with signed pieces by Belperron, Bvlgari, Cartier, Graff, Harry Winston, Hemmerle, JAR, Lacloche, Tiffany & Co., and Van Cleef & Arpels. The sale will offer 217 lots, with estimates ranging from $10,000 to $2,500,000. An exhibition by appointment will be held at Christie’s New York by appointment from April 9-12. The April 13th auction is led by ‘The Perfect Palette,’ a trio of sensational colored diamonds being offered as separate lots, which include a fancy vivid blue diamond ring of 2.13 carats ($2,000,000-3,000,000); a fancy vivid orange diamond ring of 2.34 carats ($1,500,000- 2,500,000); and a fancy vivid purplish pink diamond ring of 2.17 carats ($1,500,000-2,500,000). Additional significant colored diamonds include a fancy intense orangy pink diamond of 6.56 carats ($700,000-1,000,000); a fancy vivid yellow diamond ring of 25.55 carats ($925,000-1,225,000); and a fancy vivid purplish pink diamond ring of 3.02 carats being offered without reserve ($1,000,000- 1,500,000). -

Harry Winston Diamond Corp., Which Owns 100 Percent of the Shares in Harry Winston, Inc

Harry Winston Diamond Corporation Alexis He & Tatiana Matthews Legendary DiamondsPorter Rhodes The Hope The Jonker The Crown of Charlemagne Industry Background Rough diamond prices down 40%-50% last year, but 10% increase since beginning of 09 Polished diamonds down only 15%-20% Pricing gap between rough & polished diamonds Rough diamond prices rose 10% in 09 Industry is heavily internally connected and exclusive, especially at the highest end Diamond availability stably and slowly rising, but not so much that it’ll affect pricing negatively Industry Background Few big companies control most of the mines Control over supply=ability to manipulate prices Online diamond retailers have been unsuccessful Middle class retailers most impacted • Tiffany’s, Jared, or even De Beers Temporary shutdowns • save operations cost • keeping underground diamond savings • Boost up prices Mining method improvement likely to cut cost Industry Background Cheapest product available: $125,000 – 16.60 carats $4,000 – 0.45 carats Industry Background Jared, Tiffany both around same level De Beers can’t match either Sell mostly G grade diamonds “Blue Nile” Most expensive: $6,000 Priceless – literally (not listed) Industry Trends “If not a bottom, then a plateau” – HW CEO Robert Gannicott on pricing and demand of rough diamonds. “The fact that the people who are buying rough diamonds for polishing are coming back to the market again and are prepared to pay a bit more indicates that they, at least, have some confidence that this is probably a bottom,” he commented. Competitors share positive opinions – De Beers: Q1 2009 has been tough, but "We have begun to see signs of improvement in the market and expect this to continue as the year unfolds,” stated Stephen Lussier, chairman of De Beers Botswana.