Chapter Iii the Originals, The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emindanao Library an Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition)

eMindanao Library An Annotated Bibliography (Preliminary Edition) Published online by Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, Hawaii July 25, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii I. Articles/Books 1 II. Bibliographies 236 III. Videos/Images 240 IV. Websites 242 V. Others (Interviews/biographies/dictionaries) 248 PREFACE This project is part of eMindanao Library, an electronic, digitized collection of materials being established by the Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. At present, this annotated bibliography is a work in progress envisioned to be published online in full, with its own internal search mechanism. The list is drawn from web-based resources, mostly articles and a few books that are available or published on the internet. Some of them are born-digital with no known analog equivalent. Later, the bibliography will include printed materials such as books and journal articles, and other textual materials, images and audio-visual items. eMindanao will play host as a depository of such materials in digital form in a dedicated website. Please note that some resources listed here may have links that are “broken” at the time users search for them online. They may have been discontinued for some reason, hence are not accessible any longer. Materials are broadly categorized into the following: Articles/Books Bibliographies Videos/Images Websites, and Others (Interviews/ Biographies/ Dictionaries) Updated: July 25, 2014 Notes: This annotated bibliography has been originally published at http://www.hawaii.edu/cps/emindanao.html, and re-posted at http://www.emindanao.com. All Rights Reserved. For comments and feedbacks, write to: Center for Philippine Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa 1890 East-West Road, Moore 416 Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Email: [email protected] Phone: (808) 956-6086 Fax: (808) 956-2682 Suggested format for citation of this resource: Center for Philippine Studies, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa. -

OH-323) 482 Pgs

Processed by: EWH LEE Date: 10-13-94 LEE, WILLIAM L. (OH-323) 482 pgs. OPEN Military associate of General Eisenhower; organizer of Philippine Air Force under Douglas MacArthur, 1935-38 Interview in 3 parts: Part I: 1-211; Part II: 212-368; Part III: 369-482 DESCRIPTION: [Interview is based on diary entries and is very informal. Mrs. Lee is present and makes occasional comments.] PART I: Identification of and comments about various figures and locations in film footage taken in the Philippines during the 1930's; flying training and equipment used at Camp Murphy; Jimmy Ord; building an airstrip; planes used for training; Lee's background (including early duty assignments; volunteering for assignment to the Philippines); organizing and developing the Philippine Air Unit of the constabulary (including Filipino officer assistants; Curtis Lambert; acquiring training aircraft); arrival of General Douglas MacArthur and staff (October 26, 1935); first meeting with Major Eisenhower (December 14, 1935); purpose of the constabulary; Lee's financial situation; building Camp Murphy (including problems; plans for the air unit; aircraft); Lee's interest in a squadron of airplanes for patrol of coastline vs. MacArthur's plan for seapatrol boats; Sid Huff; establishing the air unit (including determining the kind of airplanes needed; establishing physical standards for Filipino cadets; Jesus Villamor; standards of training; Lee's assessment of the success of Filipino student pilots); "Lefty" Parker, Lee, and Eisenhower's solo flight; early stages in formation -

CHAPTER IV the JAPANESE INTERREGNUM, 1942-1945 A. The

CHAPTER IV THE JAPANESE INTERREGNUM, 1942-1945 This chapter deals with the Japanese occupation of Koronadal Valley. An alien invading force would radically change the direction of developmental process in Koronadal Valley, particularly Buayan. From an envisioned agricultural settlement serving a major function for the Commonwealth government, Koronadal Valley was transformed into a local entity whose future direction would be determined by the people no longer in accordance with the objectives for which it was established but in accordance with the dynamics of growth in response to changing times. It is ironic that an event that was calamitous in itself would provide the libertarian condition to liberate Koronadal Valley from the limiting confines of Commonwealth Act No. 441. But more than structural change, the Japanese interlude put to test the new community. The sudden departure from the scene of the two titans of the community - General Paulino Santos and Mayor Abedin - raised the urgent need for the people left behind to take stock of themselves and respond to the difficult times sans the guiding hands of its leaders. A. The Southward Thrust of Japan to Mindanao To the people of the valley, the war was received with shock, fear and trepidation. It was like a thief in the night coming when everybody was unprepared. One settler recalled: “We were afraid when we heard over the radio that the Japanese are coming. We immediately evacuated and left behind our farms and animals. We hid in the mountains of Palkan, proceeding to Glamang and then to Kiamba. Our hunger drove us to dig sweet potatoes from the farms that we passed by. -

Sagittarius Mines, Inc

SAGITTARIUS MINES, INC. 16 April 2013 Bobbie Santa Maria Researcher and Representative Business and Human Rights Resource Centre Christopher Avery Director Business and Human Rights Resource Centre Dear Ms Santa Maria and Mr Avery Thank you for the opportunity to respond to concerns regarding Sagittarius Mines Inc.’s (SMI) Tampakan Copper-Gold Project raised in the article ‘Anti-mining protest marks International Women’s Day’, published in the Business Mirror on 9 March 2013. It is important to note that our proposed Tampakan Project, located in southern Mindanao in the Philippines, is currently in the approvals phase and, as such, is not an operating mine. SMI is developing the project in line with the industry-leading sustainable development practices of our managing shareholder, Xstrata Copper, which are aligned with international standards including the United Nations (UN) Declaration of Human Rights, the International Labor Organization Conventions, the UN Global Compact, and the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights (VPSHR). Through the Tampakan Project, we aim to establish a blueprint for modern, large-scale mineral development in the Philippines. Environmental management SMI understands that water quality, security of water supply, waste management, biodiversity, and land clearing are important concerns for many of our stakeholders and we have invested significant resources to understand the potential impact of our proposed mining activities. As part of our world-class Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), we have undertaken extensive technical studies and an unprecedented level of consultation to develop rigorous environmental and social management plans to ensure that potential impacts are mitigated or avoided. During the EIA process, we consulted more than 17,000 stakeholders including our host communities, tribal leaders and councils, municipal and national government, farmers and water users, industry and business groups, and church and faith-based organizations, who had input into our project designs and environmental management plans. -

Map of Region XII – SOCCSKSARGEN Xxi

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population Report No. 1 – P REGION XII – SOCCSKSARGEN Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay August 2016 ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 1 – P 2015 Census of Population Population by Province, City, Municipality, and Barangay REGION XII - SOCCSKSARGEN Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 Philippine Statistics Authority TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword v Presidential Proclamation No. 1269 vii List of Abbreviations and Acronyms xi Explanatory Text xiii Map of Region XII – SOCCSKSARGEN xxi Highlights of the Philippine Population xxiii Highlights of the Population: Region XII – SOCCSKSARGEN xxvii Summary Tables Table A. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates for the Philippines and Its Regions, Provinces, and Highly Urbanized Cities: 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxii Table B. Population and Annual Population Growth Rates by Province, City, and Municipality in Region XII – SOCCSKSARGEN: 2000, 2010, and 2015 xxxv Table C. Total Population, Household Population, Number of Households, and Average Household Size by Region, Province, and Highly Urbanized City as of August 1, 2015: Philippines xxxvii Statistical Tables Table 1. Total Population, Household Population, Number of Households, and Average Household Size by Province, City, and Municipality as of August 1, 2015: Region XII – SOCCSKSARGEN 1 Table 2. -

Tampakan Copper-Gold Project

Preface by the Editors ✁ ✂ ✄ ♦ Tampakan Copper-Gold Project Brigitte Hamm · Anne Schax · Christian Scheper Institute for Development and Peace (INEF), commissioned by MISEREOR (German Catholic Bishops’ Organization for Development Cooperation) and Fastenopfer (Swiss Catholic Lenten Fund), in collaboration with Bread for All Imprint ■☎✆✝✞✝ ✟✠✡☛ ☞✌ 978-3-939218-42-5 Published by: Bischöfl iches Hilfswerk MISEREOR e.V. Mozartstraße 9 · 52064 Aachen · Germany Phone: +49 (0)241 442 0 www.misereor.org Contact: Armin Paasch ([email protected]) und Elisabeth Strohscheidt ([email protected]) and Katholisches Hilfswerk FASTENOPFER Alpenquai 4 · 6002 Luzern · Switzerland Phone +41 (0)41 227 59 59 www.fastenopfer.ch Contact: Daniel Hostettler ([email protected]) Authors: Brigitte Hamm, Anne Schax, Christian Scheper (Institute for Development and Peace (INEF), University of Duisburg-Essen) Photos: Elmar Noé, Armin Paasch, Elisabeth Strohscheidt, Bobby Timonera Cover photo: Paasch/MISEREOR Photos included in this study show the everyday life and present natural environment of people likely to be affected by the proposed Tampakan mine. Graphic Design: VISUELL Büro für visuelle Kommunikation, Aachen Published: July 2013 (updated version) Human Rights Impact Assessment of the Tampakan Copper-Gold Project Brigitte Hamm · Anne Schax · Christian Scheper ✍ Study Human Rights Impact Assessment of the Tampakan Copper-Gold Project Preface by the Editors ✥ ✏ ✏✑✒ ✏✓ ✔✒ ✕ ✖ ✗✘ ✓ ✏✓ ✙ ✚ ✏✑✓ ✛ ✒ ✜✓ ✏ ✕✘✓ ✢ ✣ ✤ ✢ ✛ ✢ ✜ May 2013. Partners have raised severe human rights concerns related “accident” has gained world-wide public attention: the col- to the Tampakan Copper-Gold Mine proposed by Sagitta- lapse of another garment factory in Bangladesh. Hundreds rius Mines Inc. (SMI) and its shareholders Xstrata Copper, of workers lost their lives, and many more were serious- Indophil Resources NL and Tampakan Group of Companies. -

WEDNESDAY Philippines

WEDNESDAY M 6.6 EARTHQUAKE IN COTABATO, PHILIPPINES 29 OCT 2019 FLASH UPDATE #1 1100 HRS UTC +7 The estimated population exposure by PDC REPORTED INTENSITIES: Intensity VII TulunananTulunan & Makilala, Cotabato; Kidapawan City; Malungon, Sarangani endured intensity level VII, or strong shaking. Intensity VI Davao City; Koronadal City; Cagayan de Oro City, Intensity V Tampakan, Surallah and Tupi, South Cotabato; Alabel, Sarangani. Intensity IV General Santos City; Kalilangan, Bukidnon. Intensity III was felt in Sergio Osmeña Sr., Zamboanga del Norte; Zamboanga City; Dipolog City; Molave, Zamboanga del Norte and Talakag, Bukidnon. Philippines • The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) reported that a strong M 6.4 earthquake with 7-km depth struck North Cotabato Province, Mindanao island in the Philippines on Tuesday, 29 October 2019, at 08:04 (UTC+7). The earthquake is of tectonic in origin and was located 6.92°N,125.05°E (26 km East of Tulunan, Cotabato). • About half an hour later, the earthquake has been followed by M 6.1 aftershock with 9-km depth, at 09:42 (UTC+7) and was located on 6.84°N, 125.04°E (23 km East of Tulunan, Cotabato). • PHIVOLCS advised the public to be cautious and prepare as possible damages and succeeding aftershocks are expected. • The Philippine’s National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC) immediately released an advisory on the earthquake information to several regions through facsimile, SMS, and website for further dissemination to their respective local DMO from the provincial down to the municipal levels. • There were no immediate reports of casualties or damage yet, the local DMO and the local government of North Cotabato province are conducting initial assessments and gathering information from the ground due to the expecting damages from the shallow quake. -

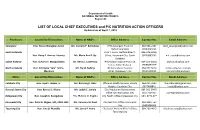

LIST of LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVES and P/C NUTRITION ACTION OFFICERS Updated As of April 7, 2016

Department of Health NATIONAL NUTRITION COUNCIL Region XII LIST OF LOCAL CHIEF EXECUTIVES and P/C NUTRITION ACTION OFFICERS Updated as of April 7, 2016 Provinces Local Chief Executives Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. Email Address Sarangani Hon. Steve Chiongbian-Solon Ms. Cornelia P. Baldelovar IPHO-Sarangani Province 083-508-2167 [email protected] Alabel, Sarangani 09393045621 South Cotabato Prov’ l. Social Welfare &Dev’t. 083-228-2184/ Hon. Daisy P. Avance- Fuentes Ms. Maria Ana D. Uy Office, Koronadal City, South 09266885635 [email protected] Cotabato Sultan Kudarat Hon. Suharto T. Mangudadatu Dr. Henry L. Lastimoso IPHO-Sultan Kudarat Province, 064-201-3032/ [email protected] Isulan, Sultan Kudarat 09088490729 North Cotabato Hon. Emmylou ”Lala” Taliño- Mr. Ely M. Nebrija IPHO-Cotabato Province 064-572-5014 [email protected] Mendoza Amas, Kidapawan City 09155119911 [email protected] Cities Local Chief Executives Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. Email Address Cotabato City Hon. Japal J. Guiani, Jr. Ms. BailinangC. Abas Office on Health Services, Rosary 064-421-3140 [email protected] Heights, Cotabato City 0917448816 [email protected] General Santos City Hon. Ronnel C. Rivera Ms. Judith C. Janiola City Population Management 083-302-3947/ Office, General Santos City 09177314457 [email protected] Kidapawan City Hon. Joseph A. Evangelista Ms. Melanie S. Espina City Health Office, Kidapawan City 064- 5771-377 Koronadal City Hon. Peter B. Miguel, MD, FPSO-HNS Ms. Veronica M. Daut City Nutrition Office, Koronadal 083-228-1763 City 09498494864 Tacurong City Hon. Lina O. Montilla Ms. Lorna P. Pama City Social Welfare &Dev’t Office, 064-200-4915 [email protected] Tacurong City List of Local Chief Executives & Municipal Nutrition Action Officers (SOUTH COTABATO) Municipality Mayor Name of NAO’s Office Address Contact No. -

American Colonial Culture in the Islamic Philippines, 1899-1942

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 2-1-2016 12:00 AM Civilizational Imperatives: American Colonial Culture in the Islamic Philippines, 1899-1942 Oliver Charbonneau The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Frank Schumacher The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Oliver Charbonneau 2016 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Asian History Commons, Cultural History Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Charbonneau, Oliver, "Civilizational Imperatives: American Colonial Culture in the Islamic Philippines, 1899-1942" (2016). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3508. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3508 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Abstract and Keywords This dissertation examines the colonial experience in the Islamic Philippines between 1899 and 1942. Occupying Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago in 1899, U.S. Army officials assumed sovereignty over a series of Muslim populations collectively referred to as ‘Moros.’ Beholden to pre-existing notions of Moro ungovernability, for two decades military and civilian administrators ruled the Southern Philippines separately from the Christian regions of the North. In the 1920s, Islamic areas of Mindanao and Sulu were ‘normalized’ and haphazardly assimilated into the emergent Philippine nation-state. -

LIST of ELEMENTARY TEACHER APPLICANTS for DEMONSTRATION TEACHING and BEHAVIORAL EVENT INTERVIEWING (Bel)

~~~' l\epnblic of t!Je ~bilippinc 1JBepartment of ~l:Juration SCHOOLS DIVISION OF SOUTH COTABATO LIST OF ELEMENTARY TEACHER APPLICANTS FOR DEMONSTRATION TEACHING AND BEHAVIORAL EVENT INTERVIEWING (BEl) DAY 1 Page 1 of3 MARCH 16, 2020 BANGA CENTRAL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL AddreSs No. Name Street I Barangay Municipality 1 ALEGRE CLAIRE S. LAMB A BANGA 2 ALVAREZ, JAY ANN A. YANGCO BANGA 3 AMARILA ANGEL IAN S. MALAYA BANGA 4 AMARILA, MARY GRACE D. YANGCO BANGA 5 ANDATUAN JOHRA A. LAMBA BANGA 6 ANDRES, MICHELLE V. LAMPARI BANGA 7 AQUINO EVA JOY P. MALAYA BANGA 8 ARTIEDA HANNAH MAE F. REYES BANGA 9 BADI JEAN D. REYES BANGA 10 BALQUIN, EMIL PATRICK N. CABULING BANGA 11 BANSALAO, RICA JANEY. SAN JOSE BANGA 12 BARNIEGO, CAREN-JOY LAMBING! BANGA 13 BLAS, ADYNA D. BENITEZ BANGA 14 BULBEQUE, CHARITY MAE L. MALAYA BANGA 15 ALAM, RUFINO M. BAKDULONG LAKE SEBU 16 APACIBLE, KRISTINE JOY T. LAMDALAG LAKE SEBU 17 AQUINO, VANESSA JANE P. POBLACION LAKE SEBU 18 AWEY, JOSEPH MARLON M. KLUBI LAKE SEBU 19 AZUELO, ELIZABETH G. TALISAY LAKE SEBU 20 BEBING, GERALDINE P. LAMDALAG LAKESEBU 21 BINATAC, CHONA N. LAMDALAG LAKESEBU 22 BLOGO, ANALYN M. LAMDALAG LAKESEBU 23 CATEL, LAILYN B. UPPER MACULAN LAKE SEBU 24 COLING, JOEMAR L. POBLACION LAKE SEBU 25 ALUTAYA, JESSA MAE B. KIBID NORALA 26 ALVAREZ, ROSEBELLE M. POBLACION NORALA 27 AMELODIN, NASSER S. PUTI NORALA 28 AMIGOS, ZULAIKA S. LAPUZ NORALA 29 ANAS, ANAB. PUTI NORALA 30 ARDA, ANN CAMILLE J. SAN MIGUEL NORALA 31 ARENGA, APRIL R. DUMAGUIL NORALA 32 ABRAGAN, IRENE G. GLAMANG POLOMOLOK 33 ALI, NADJI ROSE ANNE M. -

Tampakan Copper and Gold Mine Project Philippines

Tampakan Copper and Gold Mine project Philippines Sectors: Mining On record This profile is no longer actively maintained, with the information now possibly out of date Send feedback on this profile By: BankTrack Created before Nov 2016 Last update: Nov 1 2015 Contact: Profile owner: Evert Hassink, Milieudefensie [email protected], +31 20 5507300 Project website Sectors Mining Location About Tampakan Copper and Gold Mine project The proposed Tampakan project is a copper and gold mine in the south east of the southern Island of Mindanao, Philippines. Glencore (previously Glencore Xstrata) was the main company behind the project, until its exit in August 2015. Its local subsidiary Sagittarius Mining International (SMI) has ploughed $350 million into the $5.9 billion Tampakan project, which it describes as one of the world's largest undeveloped copper-gold deposits. The Tampakan project area contains 15 million tons of copper and nearly 18 million ounces of gold according to SMI/Glencore Xstrata. From the mining site in Tampakan, SMI planned to build a 100 km underground pipeline to ferry the minerals towards Maasim for loading to the ships. Alongside the pipeline, will be the transmission lines to a dedicated 500MW power plant. The third element of the master plan is a coal mine, not managed by SMI, near famous tourist destination Lake Sebu, that might be connected to the power plant by a 50km conveyor belt. The company claims the copper and gold mine project will generate $7.2 billion in tax and royalty revenue for the government over its 20-year mining life. -

'Gensan Is Halu-Halo': a Study of Muslim/Christian Social Relations In

‘Gensan is halu-halo’: a study of Muslim/Christian social relations in a regional city of the southern Philippines Lois Ann Hall B.A. (Hons) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Western Australia, School of Social and Cultural Studies, Discipline of Anthropology and Sociology 2010 i Abstract This thesis is set in General Santos City (Gensan), a regional city in southern Mindanao, on the geographic fringe of, but largely removed from, the secessionist conflict which has continued to blight the lives of people in the South for over four decades. The land on which the city is located was originally considered to be the homeland of both lumad (originally indigenous animist peoples) and Muslim groups. However, government- sponsored migration programmes to Mindanao, post World War II, have seen the Christian population outnumber the Muslims many times over. In the years 2001-2002, the Muslims comprised just five percent of the city‟s population. While the conflict between armed Muslim separatists and government soldiers in the hinterlands provided an everyday backdrop to life, my challenge was to discover how „ordinary‟ Muslims and Christians - neither elites nor combatants - dealt with the social reality of living in close proximity to each other in an urban setting on the edge of the main conflict zone. Through interviews I investigated the various class positions of individuals as they articulated their dreams for themselves and their families and the manner in which they went about achieving them. At the same time, I recorded the ways in which they viewed themselves, and their near neighbours, in order to elicit how social boundaries were constructed, and maintained, between the two religiously defined groups.