By Anne Twomey∗ Introduction in Australia, the Scope of the Reserve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The AWA Microphone for Harbour Bridge 75Th

..The Microphone used for the Sydney Harbour Bridge Opening ceremony. Compiled by David Burger, March 2007 with material from: - Phil Burgess Telstra, - Ted Miles – ex AWA technician. Press Release No. 94 (14/03/07) – Telstra's Sydney Harbour Bridge 75th birthday gift Phil Burgess, GMD, Public Policy and Communication, Telstra. Telstra has donated a rare microphone from its historical collection used to open the Sydney Harbour Bridge 75 years ago to the Sydney Powerhouse Museum - and it has created a bit of excitement. The Reisz microphone is a rare example of Australian technology manufactured in 1930 and was used to broadcast the 1932 opening ceremony of the Sydney Harbour Bridge to thousands of people. What has made the microphone especially significant is the signatures of all 10 dignitaries at the opening ceremony, including the NSW Premier John T Lang, NSW Governor Philip Game and the Bridge's Chief Engineer, JJC Bradfield. Speaking at the official donation event, Telstra's Group Managing Director PP&C Phil Burgess said that Telstra was proud to share this wonderful piece of Australian history with the community on the 75th birthday of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. "Every good piece of history has a story behind it and this microphone is no exception," Dr Burgess said. "Thanks to the Powerhouse Museum, many more people will be able to see and understand the role it played in unveiling a great Aussie icon." Why did Telstra have the microphone in its historical collection? The microphone became one of a collection of microphones owned by Mr Philip Geeves who was announcing for AWA (Amalgamated Wireless Australia Ltd) on the day of the Sydney Harbour Bridge opening. -

An Examination of Trinity Grammar School, Sydney, 1913 to 1976

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1989 An evangelical school in an evangelical diocese: an examination of Trinity Grammar School, Sydney, 1913 to 1976 Phillip J. Heath University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Heath, Phillip J., An evangelical school in an evangelical diocese: an examination of Trinity Grammar School, Sydney, 1913 to 1976, Master of Arts (Hons.) thesis, Faculty of Education, University of Wollongong, 1989. -

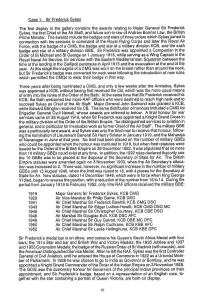

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes the First Display in the Gallery Contains

Case 1: Sir Frederick Sykes The first display in the gallery contains the awards relating to Major General Sir Frederick Sykes, the first Chief of the Air Staff, and future son-in-law of Andrew Bonnar Law, the British Prime Minister. The awards include the badges and stars of three orders which Sykes joined in connection with his services in command of the Royal Flying Corps and later the Royal Air Force, with the badge of a CMG, the badge and star of a military division KCB, and the sash badge and star of a military division GBE. Sir Frederick was appointed a Companion in the Order of St Michael and St George on 1 January 1916, while serving as a Wing Captain in the Royal Naval Air Service, for services with the Eastern Mediterranean Squadron between the time of the landing in the Gallipoli peninsula in April 1915 and the evacuation at the end of the year. At this stage the insignia of a CMG was worn on the breast rather than around the neck, but Sir Frederick’s badge was converted for neck wear following the introduction of new rules which permitted the CMGs to wear their badge in that way. Three years after being nominated a CMG, and only a few weeks after the Armistice, Sykes was appointed a KCB, without having first received the CB, which was the more usual means of entry into the ranks of the Order of the Bath. At the same time that Sir Frederick received his KCB, the Bath welcomed two more RAF officers who were destined to reach high rank and to succeed Sykes as Chief of the Air Staff: Major General John Salmond was granted a KCB, while Edward Ellington received his CB. -

Discretion and the Reserve Powers of the Crown

Discretion and the Reserve Powers of the Crown Peter H. Russell The decision of Governor General Michaëlle Jean to grant prorogation when requested by Prime Minister Harper in 2008 and 2009 led to considerable debate among students of Parliament as to the discretionary power of a governor general to reject advice of a prime minister. This article agrees with those who believe that Mme Jean did not err in acting on those specific requests but rejects the idea that it would violate constitutional convention for a governor general to ever refuse such a request from a prime minister. It further argues that in the Westminster system the monarch or her representative, in exercising any of the Crown’s legal powers in relation to Parliament, retains the right to reject a prime minister’s advice if following that advice would be highly detrimental to parliamentary democracy. That rationale applies equally to prorogation and to dissolution. recent article by Nicholas MacDonald and scholars, that “in this democratic age, the head of state James Bowden1 quite rightly stressed that or her representative should reject a prime minister’s Ain the democratic age the reserve powers advice only when doing so is necessary to protect of the Crown should be rarely used. They say that parliamentary democracy.” Those words of mine are “most scholars” agree that it is only under the “most quoted, with what I take to be approval, by MacDonald exceptional circumstances” that the governor general and Bowden in their article. The justification for the may reject the prime minister’s advice. -

The Intermittent Sovereign

THE INTERMITTENT SOVEREIGN I MAX RADIN It is impossible to escape from Austin, or rather from Aristotle, for the whole history of Western civilization is saturated with the concept of the state or community as composed of one part which gives commands and another which obeys them. Few people have held that all states were in fact so organized or that the existing states were developed in order to effectuate this concept. But most of those who have seriously thought about state organization have thought about it in these terms and a good deal of our state machinery has been formed under the influence of people who were trained to think so. And again since Aristotle, a favorite way of classifying states has been on a quantitative basis in respect of those who issued commands. This power might be wielded by one person or a few persons or a great many persons and the state was in con- sequence a monarchy, an oligarchy, or a democracy. Plainly that is not the only way in which classification might be made. Instead of how many wielded this power, we might first of all ask what kind of persons, where they came from, and how they were selected. Or we might have in mind the purposes for which the power was exercised. All these classifications have in fact been used to some extent at different times. But however classified, the prevailing idea has nearly always been that the state is based on authority, that .its essential characteristic is the fact that, somewhere, some place, there are people who give orders and others who obey them. -

The English Constitution: Walter Bagehot

The English Constitution: Walter Bagehot MILES TAYLOR Editor OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS ’ THE ENGLISH CONSTITUTION W B was born in Langport, Somerset, in , the son of a banker. After taking BA and MA degrees from University College London he studied for the bar, and was called in . However, he decided to return home and join his father’s bank, devoting his leisure to contributing literary, historical and political reviews to the leading periodicals of the s. In he returned to London, succeeding his father-in-law as editor and director of the Economist. Three books ensured Bagehot’s reputation as one of the most distinguished and influential Victorian men-of-letters: The English Constitution (), published at the height of the debate over parliamentary reform; Physics and Politics (), his application of Darwinian ideas to political science; and Lombard Street (), a study of the City of London. Walter Bagehot died in . M T is a Lecturer in Modern History at King’s College, London. He is the author of The Decline of British Radicalism, – (Clarendon Press, ) and is currently completing a biography of the last Chartist leader, Ernest Jones. ’ For almost years Oxford World’s Classics have brought readers closer to the world’s great literature. Now with over titles–– from the ,-year-old myths of Mesopotamia to the twentieth century’s greatest novels–– the series makes available lesser-known as well as celebrated writing. The pocket-sized hardbacks of the early years contained introductions by Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Graham Greene, and other literary figures which enriched the experience of reading. -

1 the Right to Refuse Cabinet Advice As a Democratic Reform1 Tyler

1 The Right to Refuse Cabinet Advice as a Democratic Reform1 Tyler Chamberlain Trinity Western University, Langley BC [email protected] Prepared for delivery at the 2018 Canadian Political Science Association Conference in Regina, SK This is a draft. Please do not cite without permission of the author. 1 Note: This is a slightly different title than that in the 2018 CPSA program. 2 Abstract Recent years have seen a rise in interest and concern over the centralization of power in the Canadian Prime Minister’s Office. Politicians, journalists, and academics alike have decried the “elected” or “friendly” dictatorship into which the office of First Minister has transformed. This paper will review several of the solutions on offer before proposing and defending an alternative solution, namely strengthening the Crown’s right to refuse advice of First Ministers, under particular circumstances. This solution will be presented via the Constitutional Traditionalism of Eugene Forsey and John Farthing, two Canadian political thinkers whose arguments have been, I suggest, vindicated by recent experience. The final section will reflect on, and hopefully clarify, the tension between strengthening the power of unelected Governors General and the project of democratic reform. It will do this by reviewing some of the relevant literature on the potential conflict between the logic of electoral competition and the logic of good governance, including, but not limited to the work of Fukuyama (2014), Zakaria (1997, 2007), and Achen & Bartels (2016). I will conclude by suggesting that a proper conception of democratic reform in a Westminster system must not be reduced to merely increasing voter input, but must balance responsiveness to voters with the ability of the House of Commons to hold the Prime Minister and Cabinet to account. -

Australian Journal of Biography and History: No

Contents Preface iii Malcolm Allbrook ARTICLES Chinese women in colonial New South Wales: From absence to presence 3 Kate Bagnall Heroines and their ‘moments of folly’: Reflections on writing the biography of a woman composer 21 Suzanne Robinson Building, celebrating, participating: A Macdougall mini-dynasty in Australia, with some thoughts on multigenerational biography 39 Pat Buckridge ‘Splendid opportunities’: Women traders in postwar Hong Kong and Australia, 1946–1949 63 Jackie Dickenson John Augustus Hux (1826–1864): A colonial goldfields reporter 79 Peter Crabb ‘I am proud of them all & we all have suffered’: World War I, the Australian War Memorial and a family in war and peace 103 Alexandra McKinnon By their words and their deeds, you shall know them: Writing live biographical subjects—A memoir 117 Nichola Garvey REVIEW ARTICLES Margy Burn, ‘Overwhelmed by the archive? Considering the biographies of Germaine Greer’ 139 Josh Black, ‘(Re)making history: Kevin Rudd’s approach to political autobiography and memoir’ 149 BOOK REVIEWS Kim Sterelny review of Billy Griffiths, Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia 163 Anne Pender review of Paul Genoni and Tanya Dalziell, Half the Perfect World: Writers, Dreamers and Drifters on Hydra, 1955–1964 167 Susan Priestley review of Eleanor Robin, Swanston: Merchant Statesman 173 Alexandra McKinnon review of Heather Sheard and Ruth Lee, Women to the Front: The Extraordinary Australian Women Doctors of the Great War 179 Christine Wallace review of Tom D. C. Roberts, Before Rupert: Keith Murdoch and the Birth of a Dynasty and Paul Strangio, Paul ‘t Hart and James Walter, The Pivot of Power: Australian Prime Ministers and Political Leadership, 1949–2016 185 Sophie Scott-Brown review of Georgina Arnott, The Unknown Judith Wright 191 Wilbert W. -

Ten Journeys to Cameron's Farm

Ten Journeys to Cameron’s Farm An Australian Tragedy Ten Journeys to Cameron’s Farm An Australian Tragedy Cameron Hazlehurst Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Hazlehurst, Cameron, 1941- author. Title: Ten Journeys to Cameron’s Farm / Cameron Hazlehurst. ISBN: 9781925021004 (paperback) 9781925021011 (ebook) Subjects: Menzies, Robert, Sir, 1894-1978. Aircraft accidents--Australian Capital Territory--Canberra. World War, 1939-1945--Australia--History. Australia--Politics and government--1901-1945. Australia--Biography. Australia--History--1901-1945. Dewey Number: 320.994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press © Flaxton Mill House Pty Ltd 2013 and 2015 Cover design and layout © 2013 ANU E Press Cover design and layout © 2015 ANU Press Contents Part 1 Prologue 13 August 1940 . ix 1 . Augury . 1 2 . Leadership, politics, and war . 3 Part 2 The Journeys 3 . A crew assembles: Charlie Crosdale and Jack Palmer . 29 4 . Second seat: Dick Wiesener . 53 5 . His father’s son: Bob Hitchcock . 71 6 . ‘A very sound pilot’?: Bob Hitchcock (II) . 99 7 . Passenger complement . 131 8 . The General: Brudenell White (I) . 139 9 . Call and recall: Brudenell White (II) . 161 10 . The Brigadier: Geoff Street . 187 11 . -

Earle Page and the Imagining of Australia

‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA ‘NOW IS THE PSYCHOLOGICAL MOMENT’ EARLE PAGE AND THE IMAGINING OF AUSTRALIA STEPHEN WILKS Ah, but a man’s reach should exceed his grasp, Or what’s a heaven for? Robert Browning, ‘Andrea del Sarto’ The man who makes no mistakes does not usually make anything. Edward John Phelps Earle Page as seen by L.F. Reynolds in Table Talk, 21 October 1926. Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760463670 ISBN (online): 9781760463687 WorldCat (print): 1198529303 WorldCat (online): 1198529152 DOI: 10.22459/NPM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This publication was awarded a College of Arts and Social Sciences PhD Publication Prize in 2018. The prize contributes to the cost of professional copyediting. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Earle Page strikes a pose in early Canberra. Mildenhall Collection, NAA, A3560, 6053, undated. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Illustrations . ix Acknowledgements . xi Abbreviations . xiii Prologue: ‘How Many Germans Did You Kill, Doc?’ . xv Introduction: ‘A Dreamer of Dreams’ . 1 1 . Family, Community and Methodism: The Forging of Page’s World View . .. 17 2 . ‘We Were Determined to Use Our Opportunities to the Full’: Page’s Rise to National Prominence . -

Volume 14 Federalism-E

Volume 14 Federalism-e Canada’s Constitutional Monarchy VERONIKA REICHERT Canadian institution.”2 Does the monarchy play University of Alberta an important, positive role in Canada today? Those who would answer “no” to its importance or its being positive have argued Anytime a royal makes an appearance at that we should abolish the Crown in Canada. an event, great public interest in royalty is However, by looking at the constitutional generated, and with that the monarchy as an structures of Canadian institutions, the design institution is brought to the attention of of our federalist democracy, and aspects of the Canadians and the Commonwealth. There is a Canadian identity, I will show that the popular opinion that the monarchy no longer monarchy does play an important, and positive, plays, and should no longer play, an important role in contemporary Canada. Further, the role in contemporary Canada, and with that a criticisms of the monarchy would be better view that the monarchy is a useless addressed through reform of the role of the appropriation of tradition, or even a harmful Crown, in terms of preserving the important symbol of oppression, the latter view taken by function the monarchy plays as well as being a Marc Chevrier who writes that “the Canadian much more accomplishable task. neomonarchy feeds illusions of false grandeur that have no meaning in America and distract One argument against the monarchy is the people from thinking that they can be that it is viewed as an archaic institution, and sovereign.”1 Others, however, see the thus it should have no place in today’s world, monarchy as an important part of modern and especially not in a federalist democracy. -

Early Scouting in New South Wales

Early Scouting in New South Wales J.X. Coutts file notes. Transcriptions (where provided) from the original (all errors intact) are included for searchability. THE GAME OF SCOUTING It was in 1907 that Baden-Powell held an experimental camp on Brownsea to test his ideas which he incorporated in his book “Scouting for Boys”, and it was in 1908 that the book first appeared to fire the imagination of boys and unintentionally start a movement which spread in a few years to all corners of the earth. Today there are eight million Scouts in over one hundred countries of the world, and the number continues to grow. Scouting grew spontaneously. B.-P. intended “Scouting for Boys” to provide programme suggestions and material for existing boys’ organisations. But as a result of the book, boys all over the country formed themselves into Scout Patrols and chose Scoutmasters from adults of their acquaintance. In that way the Scout Movement came into being and Baden-Powell became its Chief Scout. How can we account for this phenomenal spread of the game of Scouting? What is there about it that attracts like a magnet, boys of all classes, colours, languages and religions? It is because the whole scheme of Scouting is based on the normal desires of the boy. It provides a natural outlet for his bubbling energy, which is harnessed to good purpose. To the boy, Scouting is fun; it is a great game played with his comrades, as campers, pioneers and frontiermen. The aim of Scouting is to produce better citizens. It provides opportunities for developing those qualities of character which make the good citizen – honour, self-discipline and self-reliance, sense of duty and of respect for others.