Gazetteer of Historic Ironwork in Abingdon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kemble Church Before 1876 and the Restoration: As Seen in Images by John Buckler, HE Relton, Henry Taunt and an Anonymous 19Thc Watercolourist

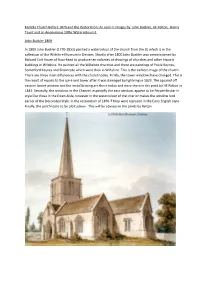

Kemble Church Before 1876 and the Restoration: As seen in images by John Buckler, HE Relton, Henry Taunt and an Anonymous 19thc Watercolourist. John Buckler 1809 In 1809 John Buckler (1770-1851) painted a watercolour of the church from the SE which is in the collection of the Wiltshire Museum in Devizes. Shortly after 1800 John Buckler was commissioned by Richard Colt Hoare of Stourhead to produce ten volumes of drawings of churches and other historic buildings in Wiltshire. He painted all the Wiltshire churches and there are paintings of Poole Keynes, Somerford Keynes and Shorncote which were then in Wiltshire. This is the earliest image of the church. There are three main differences with the church today. Firstly, the tower windows have changed. This is the result of repairs to the spire and tower after it was damaged by lightning in 1823. The squared off eastern lancet window and the metal bracing are there today and were there in the print by HE Relton in 1843. Secondly, the windows in the Chancel, especially the east window, appear to be Perpendicular in style like those in the Ewen Aisle, however in the watercolour of the interior makes the window look earlier of the Decorated Style. In the restoration of 1876-7 they were replaced in the Early English style. Finally, the porch looks to be a bit askew. This will be obvious in the prints by Relton. H. E. Relton 1843 These two prints are from ‘Sketches of Churches, with Short Descriptions’ by H. E. Relton; London (1843). He visited quite a few churches in Wiltshire, Gloucestershire and Berkshire and he wrote a few notes on each of the churches. -

Oxfordshire Local History News

OXFORDSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY NEWS The Newsletter of the Oxfordshire Local History Association Issue 128 Spring 2014 ISSN 1465-469 Chairman’s Musings gaining not only On the night of 31 March 1974, the inhabitants of the Henley but also south north-western part of the Royal County of Berkshire Buckinghamshire, went to bed as usual. When they awoke the following including High morning, which happened to be April Fools’ Day, they Wycombe, Marlow found themselves in Oxfordshire. It was no joke and, and Slough. forty years later, ‘occupied North Berkshire’ is still firmly part of Oxfordshire. The Royal Commission’s report Today, many of the people who live there have was soon followed by probably forgotten that it was ever part of Berkshire. a Labour government Those under forty years of age, or who moved in after white paper. This the changes, may never have known this. Most broadly accepted the probably don’t care either. But to local historians it is, recommendations of course, important to know about boundaries and apart from deferring a decision on provincial councils. how they have changed and developed. But in the 1970 general election, the Conservatives were elected. Prime Minister Edward Heath appointed The manner in which the 1974 county boundary Peter Walker as the minister responsible for sorting the changes came about is little known but rather matter out. He produced another but very different interesting. Reform of local government had been on white paper. It also deferred a decision on provincial the political agenda since the end of World War II. -

Floreat Domus 2013

ISSUE NO.19 MAY 2013 Floreat Domus BALLIOL COLLEGE NEWS THE ANNIVERSARY YEAR Contents Welcome to the 2013 edition of Floreat Domus. News PAGE 1 College news PAGE 32 Educate, inform, entertain Student news PAGE 13 Phoebe Braithwaite speaks to two Page 7 Page 1 alumni in the world of television Features and sheds light on the realities of the industry COLLEGE FEATURES: Page 17 A lasting legacy This Week at the PAGE 34 PAGE 19 in cosmochemistry Cinema Alice Lighton shows how Grenville Tim Adamo’s winning entry in Turner has contributed to our Balliol’s satire writing competition understanding of the solar system PAGE 20 Science and progress: and the universe growing synthetic graphene PAGE 36 Olympic reflections Jamie Warner explains how growing Richard Wheadon remembers the a synthetic version has allowed Melbourne Olympic Games and an Oxford team to study the other rowing triumphs fundamental atomic structure of a material PAGE 38 Sustainability at the Olympic Park OTHER FEATURES: Featuring sustainability expert Dorte PAGE 22 Domus Scolarium de Rich Jørgensen, who helped make Balliolo 1263–2013 the London 2012 Olympic and As we celebrate the College’s 750th Paralympics Games the greenest anniversary, John Jones reflects on Games ever changes since 1263 PAGE 41 Facing the 2020s: Pages 36–37 Pages 22–25 PAGE 26 Global Balliol: Sydney adventures in resilience Two Old Members tell us why Alan Heeks describes a project Sydney is a great place to live aimed at achieving systemic change and work by developing ‘community resilience’ PAGE 28 The ethics of narrative PAGE 42 Bookshelf non-fiction A round-up of recently published Jonny Steinberg talks about what books by Old Members readers expect from an author when the subject of the book is a real, Development news living person PAGE 44 Ghosts, gorillas and PAGE 30 Memories of a Gaudies, as the Development Romanian childhood Office takes to Twitter Alexandru Popescu talks to Carmen Bugan about her relationship with PAGE 46 Benefactors to Balliol her native country involved. -

Historic Camera

Historic Camera Newsletter © HistoricCamera.com Volume 14 No. 04 photographic dealer advertised itself as the sole wholesale agents for "Usener Portrait Lenses". Other references show that as early as 1873 and late as 1905, Usener lenses were sold at retail photographic supply houses such as Willards (The Thayer deal did Mr. Charles F. Usener was born on the 2nd of not last long), Edward Anthony, Charles July in 1823. He was a native of the German Cooper & Co. and Andrew H. Baldwin. state of Wurttemberg. Mr. Usener immigrated to America in the 1850s, where he was listed Mr. Charles F. Usener died on the 17th of in New York directories as a Daguerreian and April 1900 and is buried in Green wood Optics manufacturer. cemetery Brooklyn New York. Although he was not as well known as his lenses that In approximately 1853 Usener began making carry the names of Holmes, Booth and lens for the newly formed company Holmes, Haydens and Willards Mfg Co., Charles F. Booth and Haydens. Usener was mentioned Usener has made an important contribution to in an HB&H advertisement as the American photographic history with his lifes superintendence over the manufacture of work of producing high quality lenses. cameras ( ie. Lenses). This business relationship lasted until about 1865, just prior to the sale of Usener's company. Usener became a naturalized US citizen on October 12th, 1860. In April 1866 Willard Manufacturing Company acquired the entire business of Charles F. Usener. At that time Usener was described as the "oldest and most talented optician in the country". -

Illustrated Books

ILLUSTRATED GIFT BOOKS JONKERS RARE BOOKS 1 CATALOGUE 73 Rare Books as Gifts Contents Books make perfect gifts. Whether or not the recipient is a keen reader or collector, a History p.1 well chosen book can rarely fail to please. In an age of continuous upgrades and con- trolled obsolescence, a book has a reassuring durability and permanence and yet can be Natural History p.2 as diverse as human imagination allows. There are few gifts which are as original or convey as much thought as a rare book. Who would not be thrilled by opening a first Food & Drink p.3 edition of their favourite novel, a beautifully illustrated classic or an enthralling tale of travel or exploration, which one can return to over and over again? Angling p.3 This catalogue offers a selection of books suitable as gifts, be it as a Christmas or birth- Cricket p.5 day present for a loved one, a Christening present, a thank you present for a friend or colleague, or simply that most self indulgent of purchases, a gift for yourself. All the Rowing p.8 books have been carefully chosen and meticulously checked and researched so we can be sure that we are only offering the best copies available and priced so that they rep- River Thames p.10 resent good value. Travel p.14 The catalogue contains only a small section of our stock. Our complete stock is avail- able to be browsed in the comfortable surroundings of our new shop which is open Literature p.17 from Monday to Saturday, 10am-5.30pm, or at any time of the day or night on our website, www.jonkers.co.uk. -

THE RIVER THAMES by HENRY W TAUNT, 1873

14/09/2020 'Thames 1873 Taunt'- WHERE THAMES SMOOTH WATERS GLIDE Edited from link THE RIVER THAMES by HENRY W TAUNT, 1873 CONTENTS in this version Upstream from Oxford to Lechlade Downstream from Oxford to Putney Camping Out in a Tent by R.W.S Camping Out in a Boat How to Prepare a Watertight Sheet A Week down the Thames Scene On The Thames, A Sketch, By Greville Fennel Though Henry Taunt entitles his book as from Oxford to London, he includes a description of the Thames above Oxford which is in the centre of the book. I have moved it here. THE THAMES ABOVE OXFORD. BY THE EDITOR. OXFORD TO CRICKLADE NB: going upstream Oxford LEAVING Folly Bridge, winding along the river past the Oxford Gas-works, and passing under the line of the G.W.R., we soon come to Osney Lock (falls ft. 6 in.), close by which was the once-famous Abbey. There is nothing left to attest its former magnificence and arrest our progress, so we soon come to Botley Bridge, over which passes the western road fro Oxford to Cheltenham , Bath , &c.; and a little higher are four streams, the bathing-place of "Tumbling bay" being on the westward one. Keeping straight on, Medley Weir is reached (falls 2 ft.), and then a long stretch of shallow water succeeds, Godstow Lock until we reach Godstow Lock. Godstow Lock (falls 3 ft. 6 in., pay at Medley Weir) has been rebuilt, and the cut above deepened, the weeds and mud banks cleared out, so as to leave th river good and navigable up to King's Weir. -

List of Publications in Society's Library

OXFORD ARCHITECTURAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY RICHMOND ROOM, ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM Classified Shelf-List (Brought up-to-date by Tony Hawkins 1992-93) Note (2010): The collection is now stored in the Sackler Library CLASSIFICATION SCHEME A Architecture A1 General A2 Domestic A3 Military A4 Town Planning A5 Architects, biographies & memoirs A6 Periodicals B Gothic architecture B1 Theory B2 Handbooks B3 Renaissance architecture B4 Church restoration B5 Symbolism: crosses &c. C Continental and foreign architecture C1 General C2 France, Switzerland C3 Germany, Scandinavia C4 Italy, Greece C5 Asia D Church architecture: special features D1 General D2 Glass D3 Memorials, tombs D4 Brasses and incised slabs D5 Woodwork: roofs, screens &c. D6 Mural paintings D7 Miscellaneous fittings D8 Bells E Ecclesiology E1 Churches - England, by county E2 Churches - Scotland, Wales E3 Cathedrals, abbeys &c. F Oxford, county F1 Gazetteers, directories, maps &c. F2 Topography, general F3 Topography, special areas F4 Special subjects F5 Oxford diocese and churches, incl RC and non-conformist F6 Individual parishes, alphabetically G Oxford, city and university G1 Guidebooks G2 Oxford city, official publications, records G3 Industry, commerce G4 Education and social sciences G5 Town planning G6 Exhibitions, pageants &c H Oxford, history, descriptions & memoirs H1 Architecture, incl. church guides H2 General history and memoirs H3 Memoirs, academic J Oxford university J1 History J2 University departments & societies J3 Degree ceremonies J4 University institutions -

The History of Photography: the Research Library of the Mack Lee

THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY The Research Library of the Mack Lee Gallery 2,633 titles in circa 3,140 volumes Lee Gallery Photography Research Library Comprising over 3,100 volumes of monographs, exhibition catalogues and periodicals, the Lee Gallery Photography Research Library provides an overview of the history of photography, with a focus on the nineteenth century, in particular on the first three decades after the invention photography. Strengths of the Lee Library include American, British, and French photography and photographers. The publications on French 19th- century material (numbering well over 100), include many uncommon specialized catalogues from French regional museums and galleries, on the major photographers of the time, such as Eugène Atget, Daguerre, Gustave Le Gray, Charles Marville, Félix Nadar, Charles Nègre, and others. In addition, it is noteworthy that the library includes many small exhibition catalogues, which are often the only publication on specific photographers’ work, providing invaluable research material. The major developments and evolutions in the history of photography are covered, including numerous titles on the pioneers of photography and photographic processes such as daguerreotypes, calotypes, and the invention of negative-positive photography. The Lee Gallery Library has great depth in the Pictorialist Photography aesthetic movement, the Photo- Secession and the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, as evidenced by the numerous titles on American photography of the early 20th-century. This is supplemented by concentrations of books on the photography of the American Civil War and the exploration of the American West. Photojournalism is also well represented, from war documentary to Farm Security Administration and LIFE photography. -

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 2

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 2 On foot from Broad Street by Malcolm Graham (illustrated by Edith Gollnast, cartography by Alun Jones) Chapter 1 – Broad Street to Ship Street The walk begins at the western end of Broad Street, outside the Fisher Buildings of Balliol College (1767, Henry Keene; refaced 1870).1 ‘The Broad’ enjoyably combines grand College and University buildings with humbler shops and houses, reflecting the mix of Town and Gown elements that has produced some of the loveliest townscapes in central Oxford. While you savour the views, it is worth considering how Broad Street came into being. Archaeological evidence suggests that the street was part of the suburban expansion of Oxford in the 12th century. Outside the town wall, there was less pressure on space and the street is first recorded as Horsemonger Street in c.1230 because its width had encouraged the sale of horses. Development began on the north side of the street and the curving south side echoes the shape of the ditch outside the town wall, which, like the land inside it, was not built upon until c. 1600. Broad Street was named Canditch after this ditch by the 14th century but the present name was established by 1751.2 Broad Street features in national history as the place where the Protestant Oxford Martyrs were burned: Bishops Latimer and Ridley in 1555 and Archbishop Cranmer in 1556.3 A paved cross in the centre of Broad Street and a plaque on Balliol College commemorate these tragic events. In 1839, the committee formed to set up a memorial considered building a church near the spot but, after failing to find an eligible site, it opted instead for the Martyrs’ Memorial (1841, Sir George Gilbert Scott) in St Giles’ and a Martyrs’ aisle to St. -

The England of Henry Taunt: Victorian Photographer: His Thames. His

ROUTLEDGE LIBRARY EDITIONS: THE VICTORIAN WORLD Volume 5 THE ENGLAND OF HENRY TAUNT This page intentionally left blank THE ENGLAND OF HENRY TAUNT Victorian Photographer: his Thames. his Oxford. his Home Counties and Travels. his Portraits. Times and Ephemera Edited by BRYAN BROWN First published in 1973 by Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd This edition first published in 2016 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OXI4 4RN and by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 1973 Bryan Brown All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-1-138-66565-1 (Set) ISBN: 978-1-315-61965-1 (Set) (ebk) ISBN: 978-1-138-65929-2 (Volume 5) (hbk) ISBN: 978-1-138-65932-2 (Volume 5) (Pbk) ISBN: 978-1-315-62030-5 (Volume 5) (ebk) Publisher's Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. Disclaimer The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace. -

Of Conflict the Archaeology

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF CONFLICT Introduction by Richard Morris There can hardly be an English field that does still left with a question: why have the prosaic not contain some martial debris – an earthwork, traces of structures which were often stereotyped There is more to war than a splinter of shrapnel, a Tommy’s button. A and mass-produced become so interesting? weapons and fighting.The substantial part of our archaeological inheritance growth of interest in 20th- has to do with war or defence – hillforts, Roman Part of the answer, I think, is that there is more to century military remains is marching camps, castles, coastal forts, martello war than weapons and fighting. One reason for part of a wider span of social towers, fortified houses – and it is not just sites the growth of interest in 20th-century military evoking ancient conflict for which nations now remains is that it is not a stand-alone movement archaeology care.The 20th century’s two great wars, and the but part of the wider span of social archaeology. tense Cold War that followed, have become It encompasses the everyday lives of ordinary archaeological projects. Amid a spate of public- people and families, and hence themes which ation, heritage agencies seek military installations archaeology has hitherto not been accustomed to of all kinds for protection and display. approach, such as housing, bereavement, mourning, expectations.This wider span has Why do we study such remains? Indeed, should extended archaeology’s range from the nationally we study them? We should ask, for there are important and monumental to the routine and some who have qualms. -

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 2

Oxford Heritage Walks Book 2 On foot from Broad Street by Malcolm Graham © Oxford Preservation Trust, 2014 This is a fully referenced text of the book, illustrated by Edith Gollnast with cartography by Alun Jones, which was first published in 2014. Also included are a further reading list and a list of common abbreviations used in the footnotes. The published book is available from Oxford Preservation Trust, 10 Turn Again Lane, Oxford, OX1 1QL – tel 01865 242918 Contents: Broad Street to Ship Street 1 – 8 Cornmarket Street 8 – 14 Carfax to the Covered Market 14 – 20 Turl Street to St Mary’s Passage 20 – 25 Radcliffe Square and Bodleian Library 25 – 29 Catte Street to Broad Street 29 - 35 Abbreviations 36 Further Reading 36-37 Chapter 1 – Broad Street to Ship Street The walk begins at the western end of Broad Street, outside the Fisher Buildings of Balliol College (1767, Henry Keene; refaced 1870).1 ‘The Broad’ enjoyably combines grand College and University buildings with humbler shops and houses, reflecting the mix of Town and Gown elements that has produced some of the loveliest townscapes in central Oxford. While you savour the views, it is worth considering how Broad Street came into being. Archaeological evidence suggests that the street was part of the suburban expansion of Oxford in the 12th century. Outside the town wall, there was less pressure on space and the street is first recorded as Horsemonger Street in c.1230 because its width had encouraged the sale of horses. Development began on the north side of the street and the curving south side echoes the shape of the ditch outside the town wall, which, like the land inside it, was not built upon until c.