Democratic Crises in Latin America from 1990-2012: Explaining the Variation in Responses from Regional Intergovernmental Organizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claimants' Supplemental Memorial on the Merits

IN THE MATTER OF AN ARBITRATION UNDER THE RULES OF THE UNITED NATIONS COMMISSION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE LAW ________________________________________________________________________ CHEVRON CORPORATION and TEXACO PETROLEUM COMPANY, CLAIMANTS, v. THE REPUBLIC OF ECUADOR, RESPONDENT. ________________________________________________________________________ CLAIMANTS’ SUPPLEMENTAL MEMORIAL ON THE MERITS ________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................1 II. FACTUAL BACKGROUND .....................................................................................................3 A. The Lago Agrio Judgment is Fraudulent ............................................................3 1. The Plaintiffs Colluded With the Court to Draft the Judgment................4 2. The Judgment’s Legal Analysis Evidences Bias and Bad Faith ............12 a. Petroecuador’s Operations, Liability, and Remediation..........12 b. The Court’s Lack of Jurisdiction ...............................................18 c. The Res Judicata Effect of the Settlement and Release Agreements ...................................................................................20 3. The Judgment’s Determination of Damages Is Arbitrary, Biased, and Based on the Fraudulent Cabrera Reports.......................................24 a. Extra Petita Damages (Nearly US$ 1 Billion) ............................25 b. Soil Remediation -

Un País Entrampado (Del Plan Patriota Al TLC Con Enroque Presidencial Incluido)

Un país entrampado (Del Plan Patriota al TLC con enroque presidencial incluido) Kintto Lucas Un país entrampado (Del Plan Patriota al TLC con enroque presidencial incluido) 2006 Un país entrampado (Del Plan Patriota al TLC con enroque presidencial incluido) Kintto Lucas 1ra. Edición: Ediciones ABYA-YALA 12 de Octubre 14-30 y Wilson Casilla: 17-12-719 Teléfono: 2506-247/ 2506-251 Fax: (593-2) 2506-267 E-mail: [email protected] Sitio Web: www.abyayala.org Quito-Ecuador Los libros de TINTAJÍ El Espectador E8-13 y Shyris Teléfono: 2443-402 E-mail: [email protected] Sitio Web: www.tintaji.org Quito - Ecuador Diseño de Portada: Raúl Yépez Impresión: Docutech Quito - Ecuador ISBN: 9978-22-595-1 © Kintto Lucas © Editorial Abya-Yala - Los libros de Tintají, 2006 Impreso en Quito-Ecuador, febrero 2006. A San Cono... A Carlitos Núñez, maestro de periodistas latinoamericanos, donde esté... ÍNDICE Introducción ........................................................................... 11 La segunda fase del Plan Colombia se inició en Quito: El retrete ................................................................. 13 Una democracia -¿y unas fuerzas armadas?- muerta a puntapiés................................................................. 19 ¿El retorno de los ponchos?.................................................... 23 ¿Adónde van las fuerzas armadas?......................................... 27 Del Plan Colombia a la Guerra Global.................................. 29 Gutiérrez y los cuarenta “conspiradores” Atrapados sin salida............................................................... -

Descargar Edición #1132

26 EL SEMANARIO DE LA COMUNIDAD ECUATORIANA EN EL EXTERIOR FUNDADO EL 1O DE MARZO DE 1996 WWW.ECUADORNEWS.COM.EC EDICION NACIONAL > NUEVA YORK - NUEVA JERSEY - CONNECTICUT - CHICAGO - MINNEAPOLIS - LOS ANGELES - MIAMI - TAMPA - NY. EDICION 1132> - NY. MAYO 26-JUNIO 1º, 2021 - 50 ¢ EDICION 1132> - NY. MAYO 26-JUNIO 1º, 2021 2 WWW.ECUADORNEWS.COM.EC EDICION 1132> - NY. MAYO 26-JUNIO 1º, 2021 WWW.ECUADORNEWS.COM.EC 3 n obrero hispano que que fabrican y diseñan equipos y perdió un brazo traba- maquinarias industriales, tienen la jando en una fábrica, obligación de proveer medidas de Urecibió más de 10 seguridad para prevenir este tipo millones de dólares en una deman- de accidentes." da legal, según su abogado, el Finalmente, el señor Lavin aña- Licenciado José A. Ginarte. dió: "Tengo que agradecer mucho Efraín Lavin, de 62 años de a la firma legal de Ginarte por todo edad, nativo de Guayaquil, ganó el esfuerzo y dedicación que hicie- así una lucha legal de más de un ron posible ganar mi caso." año contra la compañía fabricante El abogado Ginarte fue el pre- de la máquina que él operaba cuan- sidente del Colegio de Abogados do sufrió el accidente. Latinoamericanos, y por más de El evento que dio comienzo a treinta y ocho (38) años representa esta demanda ocurrió cuando el a víctimas de todo tipo de acciden- señor Lavin trabajaba en una fábri- causado por defectos en la máquina en efectivo y piens retirarse en La tes en el trabajo y en la ca. Desafortunadamente el Sr. que operaba el señor Lavin. -

10571 ESP.Pdf

Universidad del Azuay Facultad de Ciencias Jurídicas Escuela de Estudios Internacionales DESARROLLO DE UN MODELO DE NEGOCIACIÓN DE LA INICIATIVA YASUNÍ ITT Tesis previa la obtención del título de Licenciada en Estudios Internacionales con mención bilingüe en Comercio Exterior Autora: Tanya Roxana Torres Castillo Director: Dr. Javier Cordero Co - Director: Ing. Antonio Torres Cuenca – Ecuador 2014 Dedicatoria Con mucho cariño dedico el presente trabajo investigativo, a mis padres y hermanos, quienes son el pilar fundamental de mi vida. A mi querida Universidad del Azuay, en cuya alma máter me eduqué no solo profesionalmente sino humana, ética y moralmente. ii Agradecimientos Dejo constancia de mis más sinceros agradecimientos a mi Director de Tesis, Dr. Javier Cordero y Co – Director Ing. Antonio Torres, por su paciencia y dirección en la realización de la presente investigación. A los profesores de la Escuela de Estudios Internacionales quienes durante 4 años guiaron mi formación académica y forjaron mi camino profesional. iii Tabla de Contenidos Dedicatoria........................................................................................................................ ii Agradecimientos .............................................................................................................. iii Índice de Ilustraciones y Tablas ...................................................................................... vi Resumen ........................................................................................................................ -

Latin American Environmental Thinking Revisited: the Polyphony of Buen Vivir

DOI 10.15517/dre.v21i2.39433 LATIN AMERICAN ENVIRONMENTAL THINKING REVISITED: THE POLYPHONY OF BUEN VIVIR Pedro Alarcón Abstract Following the guiding thread of recent Ecuadorian economic history, this paper aims to mirror the evolution of environmental discourses across the Latin American region. During the last decades of the twentieth century, increasing social environmental awareness added up to the penetration of environmental thinking into the states’ developmental policymaking. For Ecuador, this cocktail resulted in the long-run in a particular discourse: Buen vivir. Central to rationalize buen vivir was its socioecological dimension, founded on a harmonic relationship between society and nature. Buen vivir was meant to materialize in a plan to save part of the Ecuadorian Amazonia from oil drilling by leaving a significant portion of the country’s reserves under the ground in exchange for an international monetary compensation: The Yasuní-ITT initiative. Despite the fact that the plan mobilized state and society, it succumbed to forty-years of oil dependence of Ecuadorian economy, politics, and society. The termination of the initiative unveiled two antagonist environmental discourses. Whereas the state held the notion of natural resources available for commodification in the global market, society bet on alternative meanings of nature such as natural heritage and ancient peoples’ habitat and means of existence. As outcomes of the foreseeable divorce between the environmental discourses, buen vivir turned into a polyphonic concept and the struggle over a hegemonic environmental discourse resumed. It is argued that during the twenty-first century, one of the consequences of such a struggle is the construction of different meanings of development alike. -

Perspectivas Ciudadanas Del Petrã³leo En Ecuador: Variaciones

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2013 Perspectivas ciudadanas del petróleo en Ecuador: Variaciones de opiniones del desarrollo del Yasuní- ITT por barreras socioeconómicas y geográficas / Citizen Perspectives on Petroleum in Ecuador: Variances in Opinion on Yasuní-ITT evelopmeD nt across Socioeconomic and Geographic Barriers Megan Tokunaga SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Natural Resource Economics Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Oil, Gas, and Energy Commons Recommended Citation Tokunaga, Megan, "Perspectivas ciudadanas del petróleo en Ecuador: Variaciones de opiniones del desarrollo del Yasuní-ITT por barreras socioeconómicas y geográficas / itC izen Perspectives on Petroleum in Ecuador: Variances in Opinion on Yasuní-ITT Development across Socioeconomic and Geographic Barriers" (2013). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1659. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1659 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Perspectivas ciudadanas del petróleo en Ecuador: Variaciones de opiniones del desarrollo del Yasuní-ITT por barreras socioeconómicas -

Pronunciam XXXIII Perordin PARLANDINO

PRONUNCIAMIENTOS APROBADOS POR LA MESA DIRECTIVA DEL PARLANDINO EN EL MARCO DEL XXXIII PERIODO ORDINARIO DE SESIONES DECISIONES 1.- DECISIÌN 1222. POR MEDIO DE LA CUAL SE NIEGA EL LEVANTAMIENTO DE LA INMUNIDAD PARLAMENTARIA A LA HONORABLE PARLAMENTARIA ANDINA ELSA MALPARTIDA JARA. 2.- DECISION 1223. POR MEDIO DE LA CUAL SE INSTA A LA ARMONIZACIÌN DE LEGISLACIONES NACIONALES PARA LOS ESTADOS MIEMBROS DE LA CAN EN LO RELACIONADO CON LA DEFENSA DEL AMBIENTE, CONSERVACIÌN DE LA BIODIVERSIDAD Y USO SOSTENIBLE DE LOS RECURSOS NATURALES. 3.- DECISIÌN 1224. POR MEDIO DE LA CUAL SE EXALTA A LAS AUTORIDADES ANDINAS LA REGULACIÌN DEL COMPORTAMIENTO EN LOS ESTADOS ANDINOS POR MEDIO DE UNA NORMATIVIDAD COMN 4.- DECISIÌN 1225. DEL PROYECTO PARTICIPACIÌN DEMOCRÊTICA DE LOS JÌVENES EN LA INTEGRACIÌN ANDINA Y SURAMERICANA 5.- DECISIÌN 1226. MEDIANTE LA CUAL SE DECLARA AL LAGO TITICACA MARAVILLA NATURAL POR SU HISTORIA Y SUS SITIOS ARQUELOGICOS. 6.- DECISIÌN 1227. DECLARAR AREA NATURAL PROTEGIDA NACIONAL A LOS ECOSISTEMAS PARAMOS DE LA REGION PIURA œ PERU 7.- DECISIÌN 1228. IMPLEMENTACIÌN Y FUNCIONAMIIENTO DE LA RED ANDINA DE TELEVISIÌN 8.- DECISIÌN 1229. INVITACION DEL PARLAMENTO ANDINO A LAS AUTORIDADES DE TURISMO DE LOS PAÈSES ANDINOS A DESARROOLLAR Y PROMOVER PROYECTOS DE TURISMO SOCIAL EN LA REGION ANDINA. 9.- DECISIÌN 1230. EL DERECHO DE LOS ADOPTADOS A CONOCER SUS ORÈGENES BIOLÌGICOS. 10.- DECISIÌN 1231. DERECHO A DESCUENTOS Y TARIFAS ESPECIALES AL ADULTO MAYOR EN LA COMUNIDAD ANDINA. 11.- DECISIÌN 1232. SE CONDENA EN LA REGION ANDINA LOS FEMINICIDIOS COMO EXPRESIÌN EXTREMA DE LA DISCRIMINACIÌN DE LAS MUJERES. 12.-DECISIÌN 1233. POR MEDIO DE LA CUAL EL PARLAMENTO ANDINO SE PRONUNCIA AL RESPECTO DE LAS NEGOCIACIONES CAN- UNION EUROPEA. -

Auditoría Integral Ciudadana De Los Tratados De Protección Recíproca De Inversiones Y Del Sistema De Arbitraje En Materia De Inversiones En Ecuador

INFORME EJECUTIVO Auditoría integral ciudadana de los tratados de protección recíproca de inversiones y del sistema de arbitraje en materia de inversiones en Ecuador Auditoría integral ciudadana de los tratados de protección recíproca de inversiones y del sistema de arbitraje en materia de inversiones en Ecuador INFORME EJECUTIVO Mayo 2017 Quito - Ecuador COMISIONADOS Carlos Gaviria, Presidente hasta noviembre 2014 Cecilia Olivet, Vicepresidenta, asume presidencia desde diciembre 2014 Alberto Arroyo (México)x Xavier Echaide (Argentina) Osvaldo Gügliemino (Argentina) Piedad Mancero (Ecuador) Alejandro Olmos (Argentina) Hugo Ruiz (Paraguay) M. Sornarajah (Singapur) MINISTROS COMISIONADOS Pabel Muñoz, Secretario Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo Alexis Mera, Secretario Jurídico de la Presidencia Ricardo Patiño, Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores y Movilidad Beatriz Tola, Ministra Coordinadora de la Política SECRETARÍA EJECUTIVA Christian Pino EQUIPO ASESOR Guillermo Moro (Argentina) Federico Suárez (Colombia) Laura Rangel (Colombia) Luciana Ghiotto (Argentina) EQUIPO TÉCNICO (Ecuador) Adrian Cornejo Romel Tejada Diego Ramos Rafael Paredes Sebastian Espinoza Veleria Iannoti Milton Gavilanes Verónica Changoluisa Nataly Torres Rafael Pupiales Fredy Trujillo Jorge Almeida Carla Pino Geovanni Espinosa. Diseño e impresión: IAEN Tiraje: 150 ejemplares Quito, mayo 2017 Contenido INTRODUCCIÓN ........................................................................................................................ 7 RESULTADOS DE LA AUDITORÍA ............................................................................................... -

EN PAZ Y EN DESARROLLO Revista Conmemorativa Por El Vigésimo Aniversario De La Firma De Los Acuerdos De Paz Entre Ecuador Y Perú

VEINTE AÑOS: EN PAZ Y EN DESARROLLO Revista conmemorativa por el vigésimo aniversario de la firma de los acuerdos de paz entre Ecuador y Perú. Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Movilidad Humana Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores y Movilidad Humana José Valencia Director de Desarrollo Profesional del Servicio Exterior Embajador Alejandro Suárez Dirección de Relaciones Vecinales y Soberanías María Soledad Castro Equipo editorial Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Movilidad Humana VEINTE AÑOS: EN PAZ Y EN DESARROLLO Revista conmemorativa por el vigésimo aniversario de la firma de los acuerdos de paz entre Ecuador y Perú. Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Movilidad Humana VEINTE AÑOS: EN PAZ Y EN DESARROLLO Revista conmemorativa por el vigésimo aniversario de la firma de los acuerdos de paz entre Ecuador y Perú. Las opiniones expresadas en los artículos de esta publicación son responsabilidad exclusiva de sus autores y no representan la posición oficial del Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores y Movilidad Humana. Coordinador: Embajador Alejandro Suárez Equipo editorial: Mateo Bonilla y Andrea Angulo PORTADA: Medalla de reconocimiento entregada por el Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores José Ayala Lasso a las personas que participaron en el proceso de negociaciones con el Perú 1995-1998. El diseño y la leyenda corresponden al Embajador Gustavo Ruales Viel, jefe de la Misión Diplomática ecuatoriana en el Perú durante el conflicto del Cenepa, Asesor del Ministro de Relaciones Exteriores y miembro del equipo negociador ecuatoriano. CONTRAPORTADA “Paz Emblemática”, escultura en metal del artista ecuatoriano Es- tuardo Maldonado. Elaborada en 1998 con motivo de la suscripción de los acuerdos de paz con el Perú. -

Saberes Waorani Y Parque Nacional Yasuní: Plantas, Salud Y Bienestar En La Amazonía Del Ecuador

SABERES WAORANI Y PARQUE NACIONAL YASUNÍ: PLANTAS, SALUD Y BIENESTAR EN LA AMAZONÍA DEL ECUADOR i www.yasunisupport.org SABERES WAORANI Y PARQUE NACIONAL YASUNÍ: PLANTAS, SALUD Y BIENESTAR EN LA AMAZONÍA DEL ECUADOR Manuela Omari Ima Omene QUITO - ECUADOR Rafael Correa Delgado Presidente Constitucional de la República del Ecuador Ivonne Baki Secretaria de Estado para la Iniciativa Yasuní-ITT María Fernanda Espinosa Garcés Ministra Coordinadora de Patrimonio Saberes Waorani y Parque Nacional Yasuní: plantas, salud y bienestar en la Amazonía del Ecuador ISBN: 978-9942-07-339-6 Registro Nacional de Derechos de Autores: Nº 040222 Autora: Manuela Omari Ima Omene Editores: Montserrat Rios y Juan Ignacio Ramírez Segunda edición: Quito, diciembre de 2012 (500 ejemplares). Ilustraciones científicas de las plantas: María Cecilia Brito Primera edición: Quito, noviembre de 2012 (1500 ejemplares). ** El papel utilizado en la impresión proviene de bosques manejados de Indonesia y cumple con las certificaciones: Certified Quality System ISO 9001 y Long Life - Archival USE ISO 9706. ** Todos los derechos reservados. No está permitida la reproducción total o parcial de este libro por ningún medio, ni bajo ninguna forma, sin el permiso previo por escrito de la autora y la Presidencia de la República del Ecuador. Fotografías: ©Ana María Aldana, ©Heike Betz, ©Mauro Burzio, ©Iñigo de la Cerda, ©Fernando Figueiredo, ©Joe Fosse, ©Robin Foster, ©Pietro Graziani, ©Patricio Hidalgo, ©Manuela Omari Ima Omene, ©The Field Museum, ©Rutilio Paredes, ©Tim Plowman, ©Alois Speck Ferber, ©John Vandermeer y ©Laura Watson. Diseño gráfico: Montserrat Rios. Foto portada: Rostros Waorani, jaguar y danta; ©Patricio Hidalgo 2012. Foto contraportada: Parque Nacional Yasuní: ©Manuela Omari Ima Omene 2012. -

T-PUCE-5610.Pdf

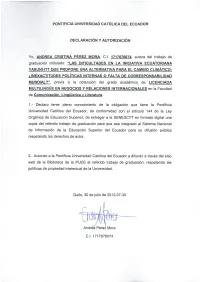

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATOLICA DEL ECUADOR FACULTAD DE COMUNICACIÓN LINGÜÍSTICA Y LITERATURA ESCUELA MULTILINGÜE DE NEGOCIOS Y RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES DISERTACIÓN DE GRADO PREVIA A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADA MULTILINGÜE EN NEGOCIOS Y RELACIONES INTERNACIONALES LAS DIFICULTADES EN LA INICIATIVA ECUATORIANA YASUNÍ-ITT QUE PROPONE UNA ALTERNATIVA PARA EL CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO: ¿INEXACTITUDES POLÍTICAS INTERNAS O FALTA DE CORRESPONSABILIDAD MUNDIAL? ANDREA CRISTINA PÉREZ MORA AGOSTO, 2012 QUITO – ECUADOR DEDICATORIA Me gustaría dedicar este esfuerzo a la naturaleza y a los pueblos no contactados del Parque Nacional Yasuní, que sin saberlo luchan por sobrevivir frente al modelo de “civilización” que amenaza su riqueza. También, a la población Huaorani que día a día busca progresar en un escenario sin rumbo fijo y escaso de oportunidades, en medio de la nostalgia. De igual manera, quiero dedicar este trabajo a todas las personas alrededor del mundo que de una u otra forma han creído en la esencia de la Iniciativa Yasuní ITT y siguen creyendo positivamente en la posibilidad y necesidad de salvar este rincón natural tan único e importante. Andrea Cristina Pérez Mora AGRADECIMIENTO Agradezco a mis padres Mery, René, Verena y Martin por siempre creer en mí y apoyarme en todo sentido, por su ayuda y confianza incondicional. A mi maestro y Director de Tesis, Paul Voerkel, por su confianza, dedicación y tiempo durante la realización de este trabajo, así como también por su interés en un buen resultado final. De igual manera, a mis maestras lectoras, Schoele Ahouraiyan y Ulla Barnickel, por sus acertadas observaciones y tiempo. A mi amigo Marian Blasberg que, sin pensarlo, me introdujo en el mundo de la Iniciativa Yasuní ITT. -

Wirtschaftsbericht 2020

Département fédéral des affaires étrangères DFAE Formulaire CH@WORLD: A754 Représentation suisse à: Quito Pays: l’Équateur Date de la dernière mise à jour: 30.07.2021 Wirtschaftsbericht 2020 0 Zusammenfassung Das Jahr 2020 war für Ecuador aus wirtschaftlicher und gesellschaftlicher Sicht ein kompliziertes und schwieriges Jahr. Während das Haushaltsdefizit, die Staatsverschuldung, der Mangel an fiskalischen Reserven, die schwache Wettbewerbsfähigkeit, das rückläufige Wirtschaftswachstum sowie die Korruption Ecuador bereits vor der Pandemie Kopfschmerzen bereiteten, kamen 2020 weitere Herausforderungen hinzu: Durch die Covid-Pandemie hat die Arbeitslosigkeit, die Informalität und somit auch die Delinquenz im Land bedeutend zugenommen. Insgesamt sind rund 22 Tausend Unternehmen zu Grunde gegangen und es wird von einer der grössten Beschäftigungskrisen in der Geschichte Ecuadors gesprochen, da momentan nur rund 30% der arbeitsfähigen Bevölkerung einer ‘angemessenen’ Beschäftigung nachgeht. Der seit Mai 2021 amtierende Präsident Guillermo Lasso verspricht jedoch eine Besserung der aktuellen Lage, die er durch wirtschaftliche, soziale und institutionelle Reformen herbeiführen will. Dabei spielen seine Impfkampagne, seine Steuerreformen, seine wirtschaftliche Öffnung (diverse Handels- und Investitionsabkommen in Sicht) sowie seine Beschäftigungsreformen eine zentrale Rolle. Eine gute Nachricht aus dem Jahre 2020 ist die die Verbesserung der Handelsbilanz Ecuadors von über 1’000%, die den Nicht-Erdölexporten zu verdanken ist und als historischer