Civilian Interaction with Armed Groups in the Syrian Conflict Wisam Elhamoui and Sinan Al-Hawat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Report Enigma of 'Baqiya Wa Tatamadad'

Report Enigma of ‘Baqiya wa Tatamadad’: The Islamic State Organization’s Military Survival Dr. Omar Ashour* 19 April 2016 Al Jazeera Centre for Studies Tel: +974-40158384 [email protected] http://studies.aljazeera.n The Islamic State (IS) organization's military survival is an enigma that has yet to be fully explained, but even defeating it militarily will only address what is just one of the symptoms of a much larger regional political crisis [Associated Press] Abstract The Islamic State organization’s motto, ‘baqiya wa tatamadad’, literally translates to ‘remaining and expanding’. Along these lines, this report examines the reality of the Islamic State organization’s continued military survival despite being targeted by much larger domestic, regional and international forces. The report is divided into three sections: the first reviews security and military studies addressing theoretical reasons for the survival of militarily weaker players against stronger parties; the second focuses on the Islamic State (IS) organisation’s military capabilities and how it uses its power tactically and strategically; and the third discusses the Arab political environment’s crisis, contradictions in the coalition’s strategy to combat IS and the implications of this. The report argues that defeating the IS organization militarily may temporarily treat a symptom of the political crisis in the region, but the crisis will remain if its roots remain unaddressed. Background After more than seven months of the US-led air campaign on the Islamic State organization and following multiple ground attacks by various (albeit at times conflicting) parties, the organisation has managed not only to survive but also to expand. -

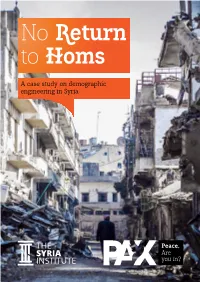

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

Pdf (2012 年 7 月 29 日にアクセス)

2014年 2 月 The 1st volume 【編集ボード】 委員長: 鈴木均 内部委員: 土屋一樹、齋藤純、ダルウィッシュ ホサム、石黒大岳、 渡邊祥子、福田安志 外部委員: 内藤正典 本誌に掲載されている論文などの内容や意見は、外部からの論稿を含め、執筆者 個人に属すものであり、日本貿易振興機構あるいはアジア経済研究所の公式見解を 示すものではありません。 中東レビュー 第 1 号 2014 年 2 月 28 日発行© 編集: 『中東レビュー』編集ボード 発行: アジア経済研究所 独立行政法人日本貿易振興機構 〒261-8545 千葉県千葉市美浜区若葉 3-2-2 URL: http://www.ide.go.jp/Japanese/Publish/Periodicals/Me_review/ ISSN: 2188-4595 ウェブ雑誌『中東レビュー』の創刊にあたって 日本貿易振興機構アジア経済研究所では 2011 年初頭に始まったいわゆる「アラブの春」と その後の中東地域の政治的変動に対応して、これまで国際シンポジウムや政策提言研究、アジ 研フォーラムなどさまざまな形で研究成果の発信と新たな研究ネットワークの形成に取り組ん できた。今回、中東地域に関するウェブ雑誌『中東レビュー』を新たな構想と装いのもとで創 刊しようとするのも、こうした取り組みの一環である。 当研究所は 1975 年 9 月刊行の『中東総合研究』第 1 号以来、中東地域に関する研究成果を 定期的に刊行される雑誌の形態で公開・提供してきた。1986 年 9 月以降は『現代の中東』およ び『中東レビュー』として年 2 回の刊行を重ねてきたが、諸般の事情により『現代の中東』は 2010 年 1 月刊行の第 48 号をもって休刊している。『中東レビュー』はこれらの過去の成果を 直接・間接に継承し、新たな環境のもとでさらに展開させていこうと企図するものである。 今回、不定期刊行のウェブ雑誌『中東レビュー』を新たに企画するにあたり、そのひとつの 核として位置づけているのが「中東政治経済レポート」の連載である。「中東政治経済レポート」 はアジ研の中東関係の若手研究者を中心に、担当する国・地域の政治・経済および社会について の情勢レポートを随時ウェブ発信し、これを年に一度再編集して年次レポートとして継続的に 提供していく予定である。 『中東レビュー』のもうひとつの核は、変動しつつある現代中東を対象とした社会科学的な 論稿の掲載である。論稿についても随時ウェブサイトに掲載していくことで、執筆から発表ま でのタイムラグを短縮し、かつこれを『中東レビュー』の総集編に収録する段階で最終的にテ キストを確定するという二段階方式を採用する。なお使用言語は当面日本語と英語の2カ国語 を想定しており、これによって従来よりも広範囲の知的交流を図っていきたいと考えている。 『中東レビュー』はアジア経済研究所内外にあって中東地域に関心を寄せる方々の、知的・ 情報的な交流のフォーラムとなることを目指している。この小さな試みが中東地域の現状につ いてのバランスの取れた理解とアジ研における中東研究の新たな深化・発展に繋がりますよう、 改めて皆様の温かいご理解とご支援をお願いいたします。 『中東レビュー』編集ボード 委員長 鈴木 均 1 目 次 ウェブ雑誌『中東レビュー』の創刊にあたって 鈴木 均 Hitoshi Suzuki・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・1 ページ 中東政治経済レポート 中東政治の変容とイスラーム主義の限界 Paradigm Shift of the Middle -

Status Report on Yarmouk Camp November 14, 2017

Status Report on Yarmouk Camp November 14, 2017 Executive Summary Following the capture of the Syria-Iraq border crossing near Abu Kamal, the Syrian government announced victory over ISIS in Syria. This announcement was made at a time when the Syrian government, supported by Hezbollah, Afghani Fatemiyoun, Iraqi Hezbollah al-Nujaba, and others, appeared poised to capture the border town of Abu Kamal – the last major population center held by ISIS in eastern Syria. However, the announcement ignored substantial ISIS strongholds elsewhere in Syria – including within the capital city of Damascus itself. ISIS entered Damascus city in April 2015, when it advanced against Free Syrian Army (FSA) aligned opposition groups and pro-government paramilitary groups in the Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp on the southern edge of the city. Since then, Yarmouk Camp has been home to a ISIS, al-Qaeda aligned Jabhat al-Nusra (now known as Hai’yat Tahrir al-Sham), FSA factions, local Palestinian factions, pro-government paramilitary fighters, and government troops, making it a microcosm of the broader conflict. This report provides a brief overview of major events affecting Yarmouk Camp and profiles the major armed groups involved throughout. Brief History The Damascus neighborhood known as Yarmouk Camp hosted a thriving Palestinian community of approximately 160,000 Palestinian refugees until the FSA and Jabhat al-Nusra captured the area in December 2012. Since then, clashes between various groups, air campaigns, and sieges have decimated the Camp’s community and infrastructure. Less than 5% of the original population remains. Civilians suffer from severe food and water shortages even as they endure the constant threat of violence and displacement at the hands of the armed actors in the area. -

Syria Regional Crisis Emergency Appeal Progress Report

syria regional crisis emergency appeal progress report for the reporting period 01 January – 30 June 2020 syria regional crisis emergency appeal progress report for the reporting period 01 January – 30 June 2020 © UNRWA 2020 The development of the 2020 Syria emergency appeal progress report was facilitated by the Department of Planning, UNRWA. About UNRWA UNRWA is a United Nations agency established by the General Assembly in 1949 and is mandated to provide assistance and protection to a population of over 5.7 million registered Palestine refugees. Its mission is to help Palestine refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, West Bank and the Gaza Strip to achieve their full potential in human development, pending a just solution to their plight. UNRWA’s services encompass education, health care, relief and social services, camp infrastructure and improvement, microfinance and emergency assistance. UNRWA is funded almost entirely by voluntary contributions. UNRWA communications division P.O. Box 19149, 91191 East Jerusalem t: Jerusalem (+972 2) 589 0224 f: Jerusalem (+972 2) 589 0274 t: Gaza (+972 8) 677 7533/7527 f: Gaza (+972 8) 677 7697 [email protected] www.unrwa.org Cover photo: UNRWA is implementing COVID-19 preventative measures in its schools across Syria to keep students, teachers and their communities safe while providing quality education. ©2020 UNRWA photo by Taghrid Mohammad. table of contents Acronyms and abbreviations 7 Executive summary 8 Funding summary: 2020 Syria emergency appeal progress report 10 Syria 11 Political, -

UNRWA-Weekly-Syria-Crisis-Report

UNRWA Weekly Syria Crisis Report, 15 July 2013 REGIONAL OVERVIEW Conflict is increasingly encroaching on UNRWA camps with shelling and clashes continuing to take place near to and within a number of camps. A reported 8 Palestine Refugees (PR) were killed in Syria this week as a result including 1 UNRWA staff member, highlighting their unique vulnerability, with refugee camps often theatres of war. At least 44,000 PR homes have been damaged by conflict and over 50% of all registered PR are now displaced, either within Syria or to neighbouring countries. Approximately 235,000 refugees are displaced in Syria with over 200,000 in Damascus, around 6600 in Aleppo, 4500 in Latakia, 3050 in Hama, 6400 in Homs and 13,100 in Dera’a. 71,000 PR from Syria (PRS) have approached UNRWA for assistance in Lebanon and 8057 (+120 from last week) in Jordan. UNRWA tracks reports of PRS in Egypt, Turkey, Gaza and UNHCR reports up to 1000 fled to Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia. 1. SYRIA Displacement UNRWA is sheltering over 8317 Syrians (+157 from last week) in 19 Agency facilities with a near identical increase with the previous week. Of this 6986 (84%, +132 from last week and nearly triple the increase of the previous week) are PR (see table 1). This follows a fairly constant trend since April ranging from 8005 to a high of 8400 in May. The number of IDPs in UNRWA facilities has not varied greatly since the beginning of the year with the lowest figure 7571 recorded in early January. A further 4294 PR (+75 from last week whereas the week before was ‐3) are being sheltered in 10 non‐ UNRWA facilities in Aleppo, Latakia and Damascus. -

REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA Received Little Or No Humanitarian Assistance in More Than 10 Months

currently estimated to be living in hard to reach or besieged areas, having REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA received little or no humanitarian assistance in more than 10 months. 07 February 2014 Humanitarian conditions in Yarmouk camp continued to worsen with 70 reported deaths in the last 4 months due to the shortage of food and medical supplies. Local negotiations succeeded in facilitating limited amounts of humanitarian Part I – Syria assistance to besieged areas, including Yarmouk, Modamiyet Elsham and Content Part I Barzeh neighbourhoods in Damascus although the aid provided was deeply This Regional Analysis of the Syria conflict (RAS) is an update of the December RAS and seeks to Overview inadequate. How to use the RAS? bring together information from all sources in the The spread of polio remains a major concern. Since first confirmed in October region and provide holistic analysis of the overall Possible developments Syria crisis. In addition, this report highlights the Map - Latest developments 2013, a total of 93 polio cases have been reported; the most recent case in Al key humanitarian developments in 2013. While Key events 2013 Hasakeh in January. In January 2014 1.2 million children across Aleppo, Al Part I focuses on the situation within Syria, Part II Information gaps and data limitations Hasakeh, Ar-Raqqa, Deir-ez-Zor, Hama, Idleb and Lattakia were vaccinated covers the impact of the crisis on neighbouring Operational constraints achieving an estimated 88% coverage. The overall health situation is one of the countries. More information on how to use this Humanitarian profile document can be found on page 2. -

Syrian Arab Republic

Humanitarian Bulletin Syrian Arab Republic Issue 43 | 13 – 26 February 2014 In this issue Truces enable delivery of some aid P.1 UNSC Resolution on humanitarian issues P.2 HIGHLIGHTS Escalation of fighting causes displacement P.2 Protection monitoring for Homs Old City evacuees P.2 Ceasefires enable delivery of Dar’a schools hit by explosions P.3 humanitarian assistance and New shelter guidelines address majority of IDPs P.3 return of civilians. SG report on children in armed conflict P.3 UN Security Council Overview of coordinated response resolution on humanitarian P.4 issues in Syria calls on UNICEF/ RRashidi Funding overview P.10 parties to the conflict to protect civilians and enable aid to reach all areas. Ceasefires enable some delivery of aid FIGURES Military truces and ceasefires have been implemented in some hard to access and Population 21.4 m besieged areas, with varying degrees of adherence, allowing partial and sporadic # of PIN 9.3 m humanitarian access. The ceasefire in Barzeh (Damascus) brokered earlier this month, has enabled the reported return of more than 1,000 people back to their homes. A UN # of IDPs 6.5 m inter-agency mission took place to the area on 25 February to conduct sectoral # of Syrian 2.5 m assessments and identify residual needs and gaps. While there the UN team met with a refugees in neighbouring representative from the countries and Governor’s office and North Africa community leaders and witnessed the mass FUNDING destruction of most parts of Barzeh, in particular the Old $ 2.3 billion City. -

"Al-Assad" and "Al Qaeda" (Day of CBS Interview)

This Document is Approved for Public Release A multi-disciplinary, multi-method approach to leader assessment at a distance: The case of Bashar al-Assad A Quick Look Assessment by the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA)1 Part II: Analytical Approaches2 February 2014 Contributors: Dr. Peter Suedfeld (University of British Columbia), Mr. Bradford H. Morrison (University of British Columbia), Mr. Ryan W. Cross (University of British Columbia) Dr. Larry Kuznar (Indiana University – Purdue University, Fort Wayne), Maj Jason Spitaletta (Joint Staff J-7 & Johns Hopkins University), Dr. Kathleen Egan (CTTSO), Mr. Sean Colbath (BBN), Mr. Paul Brewer (SDL), Ms. Martha Lillie (BBN), Mr. Dana Rafter (CSIS), Dr. Randy Kluver (Texas A&M), Ms. Jacquelyn Chinn (Texas A&M), Mr. Patrick Issa (Texas A&M) Edited by: Dr. Hriar Cabayan (JS/J-38) and Dr. Nicholas Wright, MRCP PhD (Carnegie Endowment for International Peace) Copy Editor: Mr. Sam Rhem (SRC) 1 SMA provides planning support to Combatant Commands (CCMD) with complex operational imperatives requiring multi-agency, multi-disciplinary solutions that are not within core Service/Agency competency. SMA is accepted and synchronized by Joint Staff, J3, DDSAO and executed by OSD/ASD (R&E)/RSD/RRTO. 2 This is a document submitted to provide timely support to ongoing concerns as of February 2014. 1 This Document is Approved for Public Release 1 ABSTRACT This report suggests potential types of actions and messages most likely to influence and deter Bashar al-Assad from using force in the ongoing Syrian civil war. This study is based on multidisciplinary analyses of Bashar al-Assad’s speeches, and how he reacts to real events and verbal messages from external sources. -

The Plight of Palestinian Refugees in Syria in the Camps South of Damascus by Metwaly Abo Naser, with the Support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill

Expert Analysis January 2017 Syrian voices on the Syrian conflict: The plight of Palestinian refugees in Syria in the camps south of Damascus By Metwaly Abo Naser, with the support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill Introduction: the historical role of Palestinians the Oslo Accords in 1992 and the resulting loss by both the in Syria Palestinian diaspora in general and the inhabitants of the After they took refuge in Syria after the 1948 war, al-Yarmouk refugee camp in particular of their position as Palestinians refugees were treated in the same way as a key source of both material and ideological support for other Syrian citizens. Their numbers eventually reached the Palestinian armed revolution in the diaspora. This was 450,000, living mostly in 11 refugee camps throughout Syria due in part to the failure of the various Palestinian national (UNRWA, 2006). Permitted to fully participate in the liberation factions to identify new ways of engaging the economic and social life of Syrian society, they had the diaspora – including the half million Palestinians living in same civic and economic rights and duties as Syrians, Syria – in the Palestinian struggle for the liberation of the except that they could neither be nominated for political land occupied by Israel. office nor participate in elections. This helped them to feel that they were part of Syrian society, despite their refugee This process happened slowly. After the Israeli blockade of status and active role in the global Palestinian liberation Lebanon in 1982, the Palestinian militant struggle declined. struggle against the Israeli occupation of their homeland. -

Safe Havens in Syria: Missions and Requirements for an Air Campaign

SSP Working Paper July 2012 Safe Havens in Syria: Missions and Requirements for an Air Campaign Brian T. Haggerty Security Studies Program Department of Political Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology [email protected] Copyright © July 15, 2012 by Brian T. Haggerty. This working paper is in draft form and intended for the purposes of discussion and comment. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies are available from the author at [email protected]. Thanks to Noel Anderson, Mark Bell, Christopher Clary, Owen Cote, Col. Phil Haun, USAF, Col. Lance A. Kildron, USAF, Barry Posen, Lt. Col. Karl Schloer, USAF, Sidharth Shah, Josh Itzkowitz Shifrinson, Alec Worsnop and members of MIT’s Strategic Use of Force Working Group for their comments and suggestions. All errors are my own. This is a working draft: comments and suggestions are welcome. Introduction Air power remains the arm of choice for Western policymakers contemplating humanitarian military intervention. Although the early 1990s witnessed ground forces deployed to northern Iraq, Somalia, and Haiti to protect civilians and ensure the provision of humanitarian aid, interveners soon embraced air power for humanitarian contingencies. In Bosnia, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO’s) success in combining air power with local ground forces to coerce the Serbs to the negotiating table at Dayton in 1995 suggested air power could help provide an effective response to humanitarian crises that minimized the risks of armed intervention.1 And though NATO’s