Case 3:16-Cv-01574-VC Document 198 Filed 04/25/19 Page 1 of 39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to . Commission File Number: 001-36042 INTREXON CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 26-0084895 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 20374 Seneca Meadows Parkway Germantown, Maryland 20876 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code (301) 556-9900 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Intrexon Corporation Common Stock, No Par Value Nasdaq Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

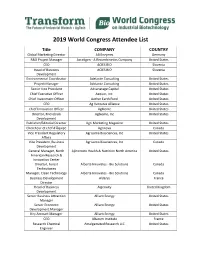

2019 World Congress Attendee List

2019 World Congress Attendee List Title COMPANY COUNTRY Global Marketing Director AB Enzymes Germany R&D Project Manager Acceligen - A Recombinetics Company United States CEO ACIES BIO Slovenia Head of Business ACIES BIO Slovenia Development Environmental Coordinator Adelante Consulting United States Project Manager Adelante Consulting United States Senior Vice President Advanatage Capital United States Chief Executive Officer Aequor, Inc. United States Chief Investment Officer Aether Earth Fund United States CEO Ag Ventures Alliance United States Chief Innovation Officer AgBiome United States Director, Microbials Agbiome, Inc United States Development Publisher/Editorial Director Agri Marketing Magazine United States Chercheur et chef d'Ãquipe Agrinova Canada Vice President Regulatory Agrisoma Biosciences, Inc United States Affairs Vice President, Business Agrisoma Biosciences, Inc Canada Development General Manager, North Ajinomoto Health & Nutrition North America United States American Research & Innovation Center Director, Forest Alberta Innovates - Bio Solutions Canada Technologies Manager, Clean Technology Alberta Innovates - Bio Solutions Canada Business Development Alderys France Director Head of Business Algenuity United Kingdom Development Senior Business Attraction Alliant Energy United States Manager Senior Economic Alliant Energy United States Development Manager Key Account Manager Alliant Energy United States CEO Altarum Institute France Research Chemical Amalgamated Research LLC United States Engineer Chemical Engineer -

STUDY on RISK ASSESSMENT: APPLICATION of ANNEX I of DECISION CP 9/13 to LIVING MODIFIED FISH Note by the Executive Secretary INTRODUCTION 1

CBD Distr. GENERAL CBD/CP/RA/AHTEG/2020/1/3 19 February 2020 ENGLISH ONLY AD HOC TECHNICAL EXPERT GROUP ON RISK ASSESSMENT AND RISK MANAGEMENT Montreal, Canada, 31 March to 3 April 2020 Item 3 of the provisional agenda* STUDY ON RISK ASSESSMENT: APPLICATION OF ANNEX I OF DECISION CP 9/13 TO LIVING MODIFIED FISH Note by the Executive Secretary INTRODUCTION 1. In decision CP-9/13, the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety decided to establish the Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group (AHTEG) on Risk Assessment and Risk Management, which would work in accordance with the terms of reference contained in annex II to that decision. In the same decision, the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Protocol requested the Executive Secretary to commission a study informing the application of annex I of the decision to (a) living modified organisms containing engineered gene drives and (b) living modified fish and present it to the online forum and the AHTEG. 2. Pursuant to the above, and with the financial support of the Government of the Netherlands, the Secretariat commissioned a study informing the application of annex I to living modified fish to facilitate the process referred to in paragraph 6 of decision CP-9/13. The study was presented to the Open-Ended Online Forum on Risk Assessment and Risk Management, which was held from 20 January to 1 February 2020, during which registered participants provided feedback and comments.1 3. -

Genetically Engineered Fish: an Unnecessary Risk to the Environment, Public Health and Fishing Communities

Issue brief Genetically engineered fish: An unnecessary risk to the environment, public health and fishing communities On November 19, 2015, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration announced its approval of the “AquAdvantage Salmon,” an Atlantic salmon that has been genetically engineered to supposedly be faster-growing than other farmed salmon. This is the first-ever genetically engineered animal allowed to enter the food supply by any regulatory agency in the world. At least 35 other species of genetically engineered fish are currently under development, including trout, tilapia, striped bass, flounder and other salmon species — all modified with genes from a variety of organisms, including other fish, coral, mice, bacteria and even humans.1 The FDA’s decision on the AquAdvantage genetically engineered salmon sets a precedent and could open the floodgates for other genetically engineered fish and animals (including cows, pigs and chickens) to enter the U.S. market. Genetically engineered salmon approved by FDA Despite insufficient food safety or environmental studies, the FDA announced its approval of the AquAdvantage Salmon, a genetically engineered Atlantic salmon produced by AquaBounty Technologies. The company originally submitted its application to the FDA in 2001 and the FDA announced in the summer of 2010 it was considering approval of this genetically engineered fish — the first genetically engineered animal intended for human consumption. In December 2012, the FDA released its draft Environmental Assessment of this genetically engineered salmon, and approved it in November 2015. This approval was made despite the 1.8 million people who sent letters to FDA opposing approval of the so-called “frankenfish,” and the 75 percent of respondents to a New York Times poll who said they would not eat genetically engineered salmon.2 The FDA said it would probably not require labeling of the fish; however Alaska, a top wild salmon producer, requires labeling of genetically engineered salmon and momentum is growing for GMO labeling in a number of states across the U.S. -

Problems in Gene Therapy and Transgenesis

Problems in Gene Therapy and Transgenesis Prof. Dr. Oliver Kayser Technische Biochemie TU Dortmund 16.03.2015 Chapter 5 - Transgenesis and Gene 1 Therapy Producing transgenic animals Purpose: Production of heterolog proteins in transgenic animals Principle: Integration of heterolog DNA with selected genetic information in fertilised eggs Methods: Mikroinjektion (-) Retrovirus vectors (-) Genetically modified embryonic stem cells (++) 16.03.2015 Chapter 5 - Transgenesis and Gene Therapy 2 16.03.2015 Chapter 5 - Transgenesis and Gene Therapy 3 Dolly 16.03.2015 Chapter 5 - Transgenesis and Gene 4 Therapy Telomers 16.03.2015 Chapter 5 - Transgenesis and Gene 5 Therapy klausurrelevant 16.03.2015 Chapter 5 - Transgenesis and Gene Therapy 6 16.03.2015 Chapter 5 - Transgenesis and Gene Therapy 7 Advantage of sheeps and goats as transgenic animals • high milk production capacity (2-3 l/ day) • short gestation period and quick maturation • low capital investment • easy handling and breeding • high expression level of proteins (35g protein/ l milk) • easy downstream processing • ongoing supply of product is guaranteed by breeding 16.03.2015 Chapter 5 - Transgenesis and Gene 8 Therapy Drug safety • Genetic stability from animal to anmial • Variation in produktion und purity during lactation • Microbial, varial, and mykoplasm contamination • TSE, Scrapie • Age and general conditions of animals 16.03.2015 Chapter 5 - Transgenesis and Gene 9 Therapy Atryn • First recombinant therapeutic protein approved in 2009 • Anticoagulant for treatment of antithrombin -

Putting the Cartel Before the Horse ...And Farm, Seeds, Soil, Peasants, Etc

Communiqué www.etcgroup.org September 2013 No. 111 Putting the Cartel before the Horse ...and Farm, Seeds, Soil, Peasants, etc. Who Will Control Agricultural Inputs, 2013? In this Communiqué, ETC Group identifies the major corporate players that control industrial farm inputs. Together with our companion poster, Who will feed us? The industrial food chain or the peasant food web?, ETC Group aims to de-construct the myths surrounding the effectiveness of the industrial food system. Table of contents Introduction: 3 Messages 3 Seeds 6 Commercial Seeds 7 Pesticides and Fertilizers 10 Animal pharma 15 Livestock Genetics 17 Aquaculture Genetics Industry 26 Conclusions and Policy Recommendations 31 Introduction: 3 Messages ETC Group has been monitoring the power and global reach of agro-industrial corporations for several decades – including the increasingly consolidated control of agricultural inputs for the industrial food chain: proprietary seeds and livestock genetics, chemical pesticides and fertilizers and animal pharmaceu- ticals. Collectively, these inputs are the chemical and biological engines that drive industrial agriculture. This update documents the continuing concentration (surprise, surprise), but it also brings us to three conclusions important to both peasant producers and policymakers… 1. Cartels are commonplace. Regulators have lost sight of the well-accepted economic principle that the market is neither free nor healthy whenever 4 companies control more than 50% of sales in any commercial sector. In this report, we show that the 4 firms / 50% line in the sand has been substan- tially surpassed by all but the complex fertilizer sector. Four firms control 58.2% of seeds; 61.9% of agrochemicals; 24.3% of fertilizers; 53.4% of animal pharmaceuticals; and, in livestock genetics, 97% of poultry and two-thirds of swine and cattle research. -

Should Genetically Modified Salmon Be Part of the Human Food Chain? Todd Biddle Cumberland Valley High School July 2011

Should Genetically Modified salmon be part of the Human Food Chain? Todd Biddle Cumberland Valley High School July 2011 Authors note: This case study is based on a real and current political upheaval amongst the United States House of Representatives, the Senate, the FDA, the consumer, and AquaBountyTechnologies®. Photo courtesy of Living in a Modern World. Modernest. Photo courtesy of AquaBounty Technologies. Aqu Advantage Fish. AquaBounty September 2010. Technologies 2011. http://www.aquabounty.com/PressRoom/ http://blog.modernest.com/2010/09/21/an-upstream- swim-to-stop-ge-salmon/ Introduction: What is for dinner? The choices for our dinner plate continue to evolve due to modern technologies and new information about human health. One way the “undesirable” genetics of edible plants and animals can be changed over time is through the process of artificial selection, a form of selective breeding. Artificial selection involves agriculturists selecting plants and animals that have the most desirable traits for producing our food. These plants and animals become the parent stock of future generations. In recent years, creating genetically modified crops and now animals has become an alternative to artificial selection. Even though genetically modified crops have been part of the human diet since the 1990s, genetically modified foods are often met with criticism from global consumers (Note: the European Commission has received responses from some European countries who wish to ban genetically modified organisms). There is a lack of public trust in their safety and they flag a number of environmental concerns. Genetically modified salmon, AquAdvantage® Salmon, engineered by the company AquaBounty Technologies may become the first genetically modified animal protein approved by the Food and Drug Administration, FDA. -

Transgenic Animals

IQP-43-DSA-4208 IQP-43-DSA-6270 TRANSGENIC ANIMALS An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science By: _________________________ _________________________ William Caproni Erik Dahlinghaus August 24, 2012 APPROVED: _________________________ Prof. David S. Adams, PhD WPI Project Advisor ABSTRACT A transgenic animal contains genes not native to its species. The use of these animals in research and medicine has dramatically increased our understanding of genetics and disease modeling. This IQP aims to provide an overview of the technical development and applications of transgenic animals, as well as the ethical, legal, and societal ramifications of creating these animals. Finally, this IQP will draw conclusions from the research performed and the information gathered. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page …………………………………………..…………………………….. 1 Abstract …………………………………………………..……………………………. 2 Table of Contents ………………………………………..…………………………….. 3 Project Objective ……………………………………….....…………………………… 4 Chapter-1: Transgenic Animal Technology …….……….…………………………… 5 Chapter-2: Applications of Transgenics in Animals …………..…………………….. 19 Chapter-3: Transgenic Ethics ………………………………………………………... 32 Chapter-4: Transgenic Legalities ……………………..………………………………. 43 Project Conclusions...…………………………………..….…………………………… 53 3 PROJECT OBJECTIVES The objective of this project was to research and present a multifaceted view of transgenics, including the technology itself and its effects on mankind. Chapter one offers an overview of the different methods for creating and testing transgenic animals. Chapter two provides information on how the different types of transgenic animals are used, and how they affect our daily lives. Chapter three presents the many ethical issues surrounding this controversial technology, and its impact on society. Chapter four describes the legal issues regarding this emerging technology and the patenting of life. -

Aquabounty Technologies, Inc. (Exact Name of the Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 _____________________________ Form 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ________________ to ________________ Commission file number: 001-36426 _____________________________ AquaBounty Technologies, Inc. (Exact name of the registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 04-3156167 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. employer incorporation or organization) identification no.) 2 Mill & Main Place, Suite 395 Maynard, Massachusetts 01754 (978) 648-6000 (Address and telephone number of the registrant’s principal executive offices) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (the “Exchange Act”): Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of exchange on which registered Common Stock, par value $0.001 per share AQB The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act of 1933. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Exchange Act during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Swimming Upstream: the Eedn to Resolve Inconsistency in the FDA's Fishy Regulatory Scheme Kelsie Kelly

Journal of Law and Policy Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 5 Fall 10-1-2018 Swimming Upstream: The eedN to Resolve Inconsistency in the FDA's Fishy Regulatory Scheme Kelsie Kelly Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/jlp Part of the Agriculture Law Commons, Food and Drug Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Kelsie Kelly, Swimming Upstream: The Need to Resolve Inconsistency in the FDA's Fishy Regulatory Scheme, 27 J. L. & Pol'y 185 (2018). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/jlp/vol27/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Policy by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. S"I11IN4 $PS%&6,17 %36 N66) %( &6S(L#6 IN*(NSIS%6N*0 IN %36 5),'S 5IS30 &64$L,%(&0 S*3616 Kelsie Kelly* The citizens of the United States rely on the federal government to maintain the safety of their food through effective regulation. As the technology used to develop food has advanced, the outermost limits of the current regulatory framework are being tested. The result has been a circuitous and ineffective attempt to regulate transgenic organisms, intended for human consumption, using multiple agencies and a patchwork of laws. The ability to incorporate DNA from nearly any organism into the genome of another provides immense potential for innovative new food products, but may also allow for unintended health and environmental consequences. Proper regulation of genetically engineered organisms is necessary in order to safely and effectively utilize biotechnology to benefit the American people. -

The Aquadvantage Salmon Controversy – a Tale of Aquaculture, Genetically Engineered Fish and Regulatory Uncertainty

The AquAdvantage Salmon Controversy – A Tale of Aquaculture, Genetically Engineered Fish and Regulatory Uncertainty The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Alain Goubau, The AquAdvantage Salmon Controversy – A Tale of Aquaculture, Genetically Engineered Fish and Regulatory Uncertainty (May 2011). Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:8789564 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The AquAdvantage Salmon Controversy – A Tale of Aquaculture, Genetically Engineered Fish and Regulatory Uncertainty Alain Goubau J.D. 2011 May 11, 2011 Paper submitted in satisfaction of course requirement only Abstract This paper discusses the controversy around the potentially imminent commercialization of the first genetically engineered animal for human food consumption in the United States. The industrialization of commercial fishing in the wake of growing demand has led to a rapid decline in wild fish stocks. Over the last 50 years, modern aquaculture has developed into an important industry, to the point that it now supplies nearly half of all the fish humans consume. Yet modern aquaculture, including its two main commercial products, shrimp and salmon, is also associated with significant environmental problems, as well as other health, social and economic ones. Partially in response to these problems, several companies and countries have turned to genetic engineering as a possible means to improve the efficiency of fish farming. -

Aquadvantage Salmon: Climate-Smart Aquaculture Climate Change Is Real

AquaBounty AquAdvantage salmon: climate-smart aquaculture Climate change is real. The impacts on wild harvest fisheries and marine aquaculture are already being felt. Little did the scientists creating a faster growing Atlantic salmon in 1989 realize that their innovative work using the new tools of molecular genetics enabling gene transfer would lead to a potential solution for enhanced seafood production in a rapidly changing and increasingly unpredictable climate. By Dave Conley, MSc, Director, Corporate Communications AquaBounty Technologies and Laura Braden, PhD, Fish Farming Expert. In the beginning the production cycle and reduce the risk to threats associated with farming in the Ironically, the early research focused marine environment. Using what had on antifreeze protein genes to solve a been learned, the scientists succeeded far different problem than warming sea on their first attempt of microinjecting temperatures. Superchill, when the ocean a growth hormone gene from Chinook water temperature falls below the freezing salmon, coupled to a promoter sequence point of salmon blood (-0.7°C), was killing from an antifreeze protein gene from salmon farmed in Atlantic Canada. ocean pout, into fertilized Atlantic salmon Researchers at Memorial University in St eggs. Of the resulting fish, several grew John’s, NL experimented with inserting much faster than their siblings. Testing an antifreeze protein gene from winter confirmed that these fish had integrated flounder into fertilized Atlantic salmon the transgene into their genomes. eggs with the goal of creating a fish that could survive superchill events in sea Named AquAdvantage® Salmon (AAS), the farms. When this line of research failed to fish is an Atlantic salmon that grows to produce the desired result, the scientists market size (4-5kg) from eyed-egg stage in turned their attention to producing a 16-20 months compared to 28-32 months faster growing Atlantic salmon to shorten for conventionally farmed Atlantic salmon.