Berlin Anthologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 2 the Period of the Weimar Republic Is Divided Into Three

CHAPTER 2 BERLIN DURING THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC The period of the Weimar Republic is divided into three periods, 1918 to 1923, 1924 to 1929, and 1930 to 1933, but we usually associate Weimar culture with the middle period when the post WWI revolutionary chaos had settled down and before the Nazis made their aggressive claim for power. This second period of the Weimar Republic after 1924 is considered Berlin’s most prosperous period, and is often referred to as the “Golden Twenties”. They were exciting and extremely vibrant years in the history of Berlin, as a sophisticated and innovative culture developed including architecture and design, literature, film, painting, music, criticism, philosophy, psychology, and fashion. For a short time Berlin seemed to be the center of European creativity where cinema was making huge technical and artistic strides. Like a firework display, Berlin was burning off all its energy in those five short years. A literary walk through Berlin during the Weimar period begins at the Kurfürstendamm, Berlin’s new part that came into its prime during the Weimar period. Large new movie theaters were built across from the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial church, the Capitol und Ufa-Palast, and many new cafés made the Kurfürstendamm into Berlin’s avant-garde boulevard. Max Reinhardt’s theater became a major attraction along with bars, nightclubs, wine restaurants, Russian tearooms and dance halls, providing a hangout for Weimar’s young writers. But Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm is mostly famous for its revered literary cafés, Kranzler, Schwanecke and the most renowned, the Romanische Café in the impressive looking Romanische Haus across from the Memorial church. -

Foreign Rights Autumn 2019

Foreign Rights Autumn 2019 Fiction Blanvalet ▪ Blessing ▪ btb ▪ Diana ▪ Goldmann ▪ Heyne Limes ▪ Luchterhand ▪ Penguin ▪ Wunderraum Contents Literary Fiction Abarbanell, Stephan: The Light of Those Days ............................................................................... 1 Barth, Rüdiger: House of Sharks ...................................................................................................... 2 Fatah, Sherko: Black September ..................................................................................................... 3 Henning, Peter: The Capable Ones .................................................................................................. 4 Kaminer, Wladimir: Tolstoy's Beard and Chechov's Shoes............................................................... 5 Keglevic, Peter: Wolfsegg ............................................................................................................... 6 Mora, Terézia: On the Rope.............................................................................................................. 7 Neudecker, Christiane: The God of the City ..................................................................................... 8 Ortheil, Hanns-Josef: He Who Dreamed of the Lions ...................................................................... 9 Sander, Gregor: Did Everything Just Right .....................................................................................10 Fiction Duken, Heike: When Life Gives You a Tortoise .............................................................................. -

Vorhaben 2019 Im Bezirk Marzahn-Hellersdorf Zur Verbesserung Der Barrierefreiheit

Vorhaben 2019 im Bezirk Marzahn-Hellersdorf zur Verbesserung der Barrierefreiheit Bauvorhaben, Straße Art der Arbeiten Stadtteil (Bezirksregion) Sozialraum Greifswalder Str. von Hönower Str. bis Taxusweg Neubau Gehweg Süd Mahlsdorf Mahlsdorf-Nord Bansiner Straße vor Seniorenheim Neubau Gehweg Hellersdorf-Süd Kaulsdorf Nord I Florastraße am Seniorenheim Neubau Gehweg Mahlsdorf Mahlsdorf-Nord Lübzer Str. 9 Gehweg und GWÜ Mahlsdorf Mahlsdorf-Nord Melanchthonstr. 96 Lückenschluss Mahlsdorf Mahlsdorf-Nord Terwestenstraße 11 bis Dahlwitzer Str. Gehweg Mahlsdorf Mahlsdorf-Nord Köpenicker Straße - Südbereich Gehweg Biesdorf Biesdorf-Süd Dohlengrund von Grabensprung bis Anschluss U-Bahn Neubau Gehweg Biesdorf Biesdorf-Süd Maratstraße Gehweg Biesdorf Oberfeldstraße Ringenwalder Straße 23 Gehweg Sanierung Marzahn-Mitte Marzahn-Ost Marzahner Franz-Stenzer-Straße 53-55 Gehweg Sanierung Marzahn-Mitte Promenade Kemberger Straße - Haltestelle Gehweg Sanierung Marzahn-Mitte Marzahn-Ost Alt-Mahrzahn Gehweg Sanierung Marzahn-Süd Alt-Marzahn Rudolf-Leonhardt-Str. (MUF) Gehweg Marzahn-Mitte Ringkolonnaden Straße An der Schule zwischen Zufahrt und Wendehammer Pestalozzistraße Schulweg (provisorisch in Asphalt) Mahlsdorf Alt-Mahlsdorf Hultschiner Damm Lückenschlüsse 5 Teilstücke Gehweg Mahlsdorf Mahlsdorf-Süd Wielandstr. 9-10 Gehweg Mahlsdorf Mahlsdorf-Süd Kiekemaler Str. 11-12 Gehweg Mahlsdorf Mahlsdorf-Süd Feldberger Ring 6 Gehweg barrierefreie Anbindung Hellersdorf-Süd Kaulsdorf Nord II Hellersdorfer Str. 205-207 Gehweg Hellersdorf-Süd Kaulsdorf Nord II Florastr. -

The City Anthology: Definition of a Type

Marven, L 2020 The City Anthology: Definition of a Type. Modern Languages Open, 2020(1): 52 pp. 1–30. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.279 ARTICLE The City Anthology: Definition of a Type Lyn Marven University of Liverpool, GB [email protected] This article uses a corpus of over one hundred and fifty Berlin literary anthologies from 1885 to the present to set out the concept of a ‘city anthology’. The city anthology encompasses writing from as well as about the city, and defines itself through a broad sense of connection to the city rather than thematic subject matter as such. This article uses the example of Berlin to set out the unique traits of the city anthology form: the affective connection between authors, editors, readers, texts and the city; diversity of contributors and literary content; and a tendency towards reportage. It further uses the corpus to identify four key types of city anthology – survey, snapshot, retrospective and memory anthology – and to argue for a functional rather than formal definition of the anthology. Finally, Berlin anthologies challenge precepts of that city’s literary history in two key ways: in mapping different historical trajectories across the nineteenth to twenty-first centuries, and in particular countering the focus on the much better known city novel. The often-overlooked city anthology thus constitutes a specific form of city literature as well as anthology. As a literary manifestation – not just a representation – of the city, city anthologies inhabit a border space between literary geographies and urban imaginaries with the potential to open up an affective dimension in urban studies. -

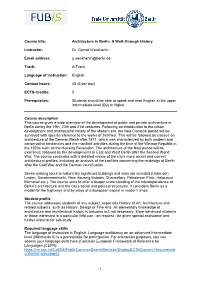

Architecture in Berlin. a Walk Through History Instructor

Course title: Architecture in Berlin. A Walk through History Instructor: Dr. Gernot Weckherlin Email address: [email protected] Track: A-Track Language of instruction: English Contact hours: 48 (6 per day) ECTS-Credits: 5 Prerequisites: Students should be able to speak and read English at the upper intermediate level (B2) or higher. Course description This course gives a wide overview of the development of public and private architecture in Berlin during the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries. Following an introduction to the urban development and architectural history of the Modern era, the Neo-Classical period will be surveyed with special reference to the works of Schinkel. This will be followed by classes on architecture of the German Reich after 1871, which was characterized by both modern and conservative tendencies and the manifold activities during the time of the Weimar Republic in the 1920s such as the Housing Revolution. The architecture of the Nazi period will be examined, followed by the developments in East and West Berlin after the Second World War. The course concludes with a detailed review of the city’s more recent and current architectural profiles, including an analysis of the conflicts concerning the re-design of Berlin after the Cold War and the German reunification. Seven walking tours to historically significant buildings and sites are included (Unter den Linden, Gendarmenmarkt, New Housing Estates, Chancellory, Potsdamer Platz, Holocaust Memorial etc.). The course aims to offer a deeper understanding of the interdependence of Berlin’s architecture and the city’s social and political structures. It considers Berlin as a model for the highways and by-ways of a European capital in modern times. -

UWE G. BACHMANN, Müggelheim: Stadtvilla Im Bauhausstil Auf Wassergrundstück Mit Bootssteg- Erstbezug

UWE G. BACHMANN, Müggelheim: Stadtvilla im Bauhausstil auf Wassergrundstück mit Bootssteg- Erstbezug Villa in 12559 Berlin / Köpenick Sie möchten sofort und online die Objektanschrift zu dieser Immobilie erfahren? Bachmann Immobilien GmbH · Hultschiner Damm 40 · 12623 Berlin-Mahlsdorf Tel.: 030 56545455 · Fax: 030 56545459 · email: [email protected] Amtsgericht Charlottenburg · Handelsregister-Nr.: 75510 · Ust-IdNr.: DE208291974 Geschäftsführer: Uwe G. Bachmann Daten im Überblick Objektart: Haus Objekttyp: Villa Nutzungsart: Wohnen Vermarktungsart: Kauf Wohnfläche: 222,00 m² Kaufpreis: 930000,00 EUR Baujahr: 2016 Provision: 7,14 % Käuferprovision inkl. MwSt. Energieausweistyp: Endenergiebedarf Energieausweis gültig bis: 2026-07-17 Endenergiebedarf: 57,30 Energieeffizienzklasse: B Bachmann Immobilien GmbH · Hultschiner Damm 40 · 12623 Berlin-Mahlsdorf Tel.: 030 56545455 · Fax: 030 56545459 · email: [email protected] Amtsgericht Charlottenburg · Handelsregister-Nr.: 75510 · Ust-IdNr.: DE208291974 Geschäftsführer: Uwe G. Bachmann 2 Objektbeschreibung: Dieses Objekt wird über BACHMANN Immobilien im Alleinauftrag angeboten. Die im Bauhausstil erbaute Architekten-Villa bietet Ihnen auf drei Wohnebenen (Halbgeschoss-Versatz) ca. 222 m² Wohnfläche mit Wohn-Essbereich, großzügiger Diele, 3 Schlafzimmern, großer Galerie als Arbeitszimmer, Wintergarten, 2 Dachterrassen, 2 Ankleideräumen, Gästebad, Masterbad, Abstell- / Vorratsraum, Hauswirtschaftsraum, offenen Vorkeller und Hausanschlussraum. Die Doppelgarage mit zwei anliegenden -

Unternehmensservice Lichtenberg

Standortvorteile: Unternehmensservice · Citynähe und kurze Wege ins Umland Lichtenberg · Schnelle Anbindung an Autobahnen · Gewerbeareal Berlin eastside (gemeinsam mit Marzahn- Hellersdorf) · 10 gut erschlossene Gewerbegebiete mit über 400 ha Fläche · Mix aus Traditionsunternehmen, Hidden Champions, Zwischen Tradition und Moderne spezialisierten Industriezulieferern sowie innovativen Der Bezirk Lichtenberg ist ein in Teilen historisch gewachsener Industrie- Dienstleistungen und Handwerk standort. Er verfügt über eine ausgezeichnete Infrastruktur und sehr · Büroflächen für jeden Bedarf gute Verkehrsverbindungen. Für Gewerbe, Dienstleistungen und Handel · Vielfältiges Angebot an Wohnraum in unterschiedlichen Lagen bietet Lichtenberg günstige Standortbedingungen. Lichtenberg gehört · Kindertagesstätten und Schulen für jeden Anspruch mit seinen 5.229 ha zu den kleineren Bezirken der Hauptstadt. Lichtenberg bietet · Rummelsburger Bucht als Wohn- und Freizeitquartier · Tierpark Friedrichsfelde – Europas größter Landschaftstierpark Ihre Ansprechpartner zum Unternehmensservice · Hochschule für Wirtschaft und Recht Berlin in Lichtenberg · Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin · Dong Xuan Center – asiatisches Handels- und Kulturzentrum Bezirksamt Lichtenberg Berlin Partner für Wirtschaft · Sportforum und Olympiastützpunkt von Berlin und Technologie · Urbanes und dörfliches Flair, Freiräume Marion Nüske Tomasz Pawlowski · Gedenkstätte Hohenschönhausen Tel +49 30 90296-4338 Tel +49 30 90296-4334 · Parks, Gärten, Natur- und Landschaftsschutzgebiete -

1 German (Div I)

GERMAN (DIV I) Chair: Professor JULIE CASSIDAY Professors: H. DRUXES**, G. NEWMAN. Assistant Professor: C. KONÉ. Visiting Assistant Professor: C. MANDT. Lecturer: E. KIEFFER§. Teaching Associates: T. HADLEY, T. LEIKAM. STUDY OF GERMAN LANGUAGE AND GERMAN-LANGUAGE CULTURE The department provides language instruction to enable the student to acquire all four linguistic skills: understanding, speaking, reading, and writing. German 101-W-102 stresses communicative competence and covers German grammar in full. German 103 combines a review of grammar with extensive practice in reading and conversation. German 104 aims to develop facility in speaking, writing, and reading. German 120 is a compactintensive communicative German course that strives to cover two semesters of the language in one. German 201 emphasizes accuracy and idiomatic expression in speaking and writing. German 202 combines advanced language study with the examination of topics in German-speaking cultures. Each year the department offers upper-level courses treating various topics from the German-language intellectual, cultural, and social world in which reading, discussion and writing are in German. Students who have studied German in secondary school should take the placement test given during First Days in September to determine which course to take. STUDY ABROAD The department strongly encourages students who wish to attain fluency in German to spend a semester or year studying in Germany or Austria, either independently or in one of several approved foreign study programs. German 104 or the equivalent is the minimum requirement for junior-year abroad programs sponsored by American institutions. Students who wish to enroll directly in a German-speaking university should complete at least 201 or the equivalent. -

Standort Berlin Florastraße

DB Systel GmbH 12623 Berlin-Mahlsdorf | Florastraße 133 – 136 | Germany How to reach us: By public transport: From all major central S-Bahn stations (Zoologischer Garten, Hauptbahnhof, Friedrichstraße, Ostbahnhof, Alexanderplatz, Ostkreuz, Lichtenberg) take S-Bahn line S5 (for Strausberg) to Mahlsdorf. Exit Mahlsdorf station and cross over Hönower Straße, then continue parallel to the S-Bahn along the railway embankment path. This path takes you directly to DB Systel on Florastraße. From Tegel Airport take the TXL transfer bus to the central station (Hauptbahnhof) and from there Stettin continue as described above. A11 /Rostock g A10 AB-Dr. Havelland From Schönefeld Airport take bus 171 to Schönefeld Hambur AB-Dr. Pankow AB-Dr. Schwanebeck S-Bahn station and from there take the S9 to Ostkreuz, A114 then change to the S5 (for Strausberg) and travel to A10 Abf. Berlin Marzahn Mahlsdorf S-Bahn station. Take the embankment path to Florastraße as described A10 Abf. Berlin DB Systel Hellersdorf A100 Fr above. B1/B5 ankfurt/Oder B1/B5 AB-Dr. A115 Funkturm By car: Travel on the A10 Berliner Ring to Berlin's north- AB-Kreuz A10 Zehlendorf A113 eastern periphery, exiting at either the Berlin-Marzahn AB-Dr. or the Berlin-Hellersdorf junction. From the Berlin- Werde A10 AB-Dr. AB-Dr. Schönefelder Potsdam Drewitz AB-Dr. Marzahn junction take Altlandsberger Chaussee A9 Kreuz Spreeau A13 towards Zentrum and after about 3 km turn left for Hannover/Frankfurt/Nürnberg Dresden Dahlwitz/Hoppegarten, being careful not to follow the second sign, but staying in the righthand lane on Mahlsdorfer Straße, continuing along here for about Stettin 3.6 km. -

The East German Writers Union and the Role of Literary Intellectuals In

Writing in Red: The East German Writers Union and the Role of Literary Intellectuals in the German Democratic Republic, 1971-90 Thomas William Goldstein A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Konrad H. Jarausch Christopher Browning Chad Bryant Karen Hagemann Lloyd Kramer ©2010 Thomas William Goldstein ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Thomas William Goldstein Writing in Red The East German Writers Union and the Role of Literary Intellectuals in the German Democratic Republic, 1971-90 (Under the direction of Konrad H. Jarausch) Since its creation in 1950 as a subsidiary of the Cultural League, the East German Writers Union embodied a fundamental tension, one that was never resolved during the course of its forty-year existence. The union served two masters – the state and its members – and as such, often found it difficult fulfilling the expectations of both. In this way, the union was an expression of a basic contradiction in the relationship between writers and the state: the ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED) demanded ideological compliance, yet these writers also claimed to be critical, engaged intellectuals. This dissertation examines how literary intellectuals and SED cultural officials contested and debated the differing and sometimes contradictory functions of the Writers Union and how each utilized it to shape relationships and identities within the literary community and beyond it. The union was a crucial site for constructing a group image for writers, both in terms of external characteristics (values and goals for participation in wider society) and internal characteristics (norms and acceptable behavioral patterns guiding interactions with other union members). -

“The Double Bind” of 1989: Reinterpreting Space, Place, and Identity in Postcommunist Women’S Literature

“THE DOUBLE BIND” OF 1989: REINTERPRETING SPACE, PLACE, AND IDENTITY IN POSTCOMMUNIST WOMEN’S LITERATURE BY JESSICA LYNN WIENHOLD-BROKISH DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctorial Committee: Associate Professor Lilya Kaganovsky, Chair; Director of Research Professor Nancy Blake Professor Harriet Murav Associate Professor Anke Pinkert Abstract This dissertation is a comparative, cross-cultural exploration of identity construction after 1989 as it pertains to narrative setting and the creation of literary place in postcommunist women’s literature. Through spatial analysis the negotiation between the unresolvable bind of a stable national and personal identity and of a flexible transnational identity are discussed. Russian, German, and Croatian writers, specifically Olga Mukhina, Nina Sadur, Monika Maron, Barbara Honigmann, Angela Krauß, Vedrana Rudan, Dubravka Ugrešić, and Slavenka Drakulić, provide the material for an examination of the proliferation of female writers and the potential for recuperative literary techniques after 1989. The project is organized thematically with chapters dedicated to apartments, cities, and foreign lands, focusing on strategies of identity reconstruction after the fall of socialism. ii To My Family, especially Mom, Dad, Jeffrey, and Finnegan iii Table of Contents Chapter One: Introduction: “We are, from this perspective, -

70 Jahre I 70 Künstler I 70 Ateliers

anders - 70 jahre I 70 künstler I 70 ateliers 20.10.2018 bis 11.11.2018 galerie des bbk rheinland-pfalz am judensand 57b, 55122 mainz 6.12.2018 bis 6.1.2019 vertretung des landes rheinland-pfalz beim bund und bei der europäischen union in den ministergärten 6, 10117 berlin für die unterstützung danken wir der stiftung rheinland-pfalz für kultur 70 jahre und kein bisschen weise leise der berufsverband bildender künstlerinnen und künstler rheinland-pfalz wird 70 jahre alt. feiern sie mit uns – wir laden sie herzlich dazu ein! in einer fotoausstellung zeigen wir dazu einblicke in die ateliers von 70 unserer mitglieder. Sylvia Richter-Kundel 1. Vorsitzende des BBK Rheinland-Pfalz im Bundesverband e.V. Die Künstlerinnen und Künstler: Ader, Reinhard │ Albert, Roland │ Balbach, Petra │ Barth, Rolf Olma, Veronika │ Pasieka, Manfred │ Pauly, Monica Beck, Wolfgang │ Bendel, Gregor │ Bitzigeio, Werner Peters, Nicole │ Quast, Ulrike von │ Quednau, Usch Blanke, Wolfgang │ Bozem, Artur │ Brandstifter Reindell, Ursula │ Reinmann, Christian │ Richter-Kundel, Sylvia Daubländer, Rita │ │DeePee │ Ehrnsperger, Petra Roller, Mathilde │ Ropertz, Dagmar C. │ Rousin, Karol Eller, Rita │ Faber, Ulla │ Helmy, Birgid │ Hermann, Christel Rump, Alois │ Schalenberg, Sven │ Schindler, Anja Christian Heuchel + Gunter Klag │ Hülsewig, Ursula Schöneich, Martin │ Schreiber, Ulrich │ Sprenger, Anne-Marie Huth, Karin │ Kemper-Herlet, Cornelia │ Klein, Sylvia Stäglich, Alice │ Steier, Horst │Steimer, Sabine │ Steiner, Elke Klinger, Gabi │ Köcher, Peter │Krell, Susanne │ Kühn,