The Cratered Earth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The High-Pressure Mineral Inventory of Shock Veins from the Steen River Impact Structure

46th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2015) 2512.pdf The high-pressure mineral inventory of shock veins from the Steen River impact structure. Walton E.L., Sharp T. G. and Hu J. 1MacEwan University, Department of Physical Sciences, 10700 104 Ave, Edmonton, AB, T5J 2S2, Canada ([email protected] / [email protected] ), 2University of Alberta, Department of Earth & Atmospheric Sciences, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2E3, Canada. 3Arizona State University, School of Earth & Space Ex- ploration,Tempe, AZ 85287-1404, USA. Introduction: The Steen River impact struc- equipped with five WDS spectrometers. Raw data ture (SRIS; 59o31'N, 117o39’W) is a buried complex were corrected using the ZAF procedure. The excel crater with an apparent diameter of ~25 km [1]. The spreadsheets of [6,7] where used to recast chemical SRIS is the largest known impact structure in the analyses of amphiboles and garnets following the IMA Western Canada Sedimentary Basin and is a producer reccomentations. Micro-Raman spectra of various and host of oil and gas reservoirs [1]. The target rocks phases were obtained with point measurements, using comprise a 70 m layer of Missippian calcareous shale a Bruker SENTERRA instrument. The 100X objective underlain by a thick (1530 m) sequence of Devonian of a petrographic microscope was used to focus the marine sedimentary rocks including carbonates and excitation laser beam (532 nm line of Ar+ laser) to a evaporates. This ~1.6 km thick sedimentary cover focal spot size of ~1 µm. TEM sections will be pre- overlies Precambrian basement rocks (primarily gran- pared using an FEI Nova200 NanoFab dual-beam FIB, ite / gneiss / granodiorite). -

Remove This Report from Blc8. 25

.:WO _______CUfe\J-&£sSU -ILtXJZ-.__________ T REMOVE THIS REPORT FROM BLC8. 25 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY This report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey standards and nomenclature. Prepared by the Geological Survey for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration U )L Interagency Report: 43 GUIDE TO THE GEOLOGY OF SUDBURY BASIN, ONTARIO, CANADA (Apollo 17 Training Exercise, 5/23/72-5/25/72) by I/ 2/ Michael R. Dence , Eugene L. Boudette 2/ and Ivo Lucchitta May 1972 Earth Physics Branch Dept. of Energy, Mines & Resources Ottawa, Canada 21 Center of Astrogeology U. S. Geological Survey Flagstaff, Arizona 86001 ERRATA Guide to the geology of Sudbury Basin, Ontario, Canada by Michael R. Dence, Eugene L. Boudette, and Ivo Lucchitta Page ii. Add "(photograph by G. Mac G. Boone) 11 to caption. iii. P. 2, line 5; delete "the" before "data", iv. P. 1, line 3; add "of Canada, Ltd." after "Company", iv. P. 1, line 7; delete "of Canada" after "Company". v. Move entire section "aerial reconnaissance....etc..." 5 spaces to left margin. 1. P. 2, line 6; add "moderate to" after "dips are". 1. P. 2, line 13; change "strike" to "striking". 2. P. 1, line 2; change "there" to "these". 2. P. 2, line 7; change "(1) breccias" to "breccias (1)". 2. P. 3, line 3; add "slate" after "Onwatin". 4. P. 1, line 7; change "which JLs" to "which are". 7. P. 1, line 9; add "(fig. 3)" after "surveys". 7. P. -

The Subsurface Structure of Oblique Impact Craters

The subsurface structure of oblique impact craters Dissertation vorgelegt von Dipl.-Geol. Michael H. Poelchau vom Fachbereich Geowissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) Berlin, 2010 The subsurface structure of oblique impact craters Dissertation vorgelegt von Dipl.-Geol. Michael H. Poelchau vom Fachbereich Geowissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat.) Berlin, 2010 Gutachter: 1. PD Dr. Thomas Kenkmann 2. Prof. Wolf-Uwe Reimold Tag der Disputation: 23.02.2010 Statement regarding the contributions of the author and others to this thesis This thesis is comprised of three published, peer-reviewed articles and one submitted manuscript, which each form separate chapters within this thesis. The chapters “Introduction” and “General Conclusions” were written especially for this thesis. The PhD candidate is the first author of two of these articles, and the second author of the third article. The PhD candidate is also the first author of a manuscript currently submitted to Earth and Planetary Science Letters. Therefore, these four chapters have their own introduction, methodology, discussion, conclusions and references. The articles and manuscripts used in this thesis are the following: Poelchau, M. H., and T. Kenkmann, 2008. Asymmetric signatures in simple craters as an indicator for an oblique impact direction, Meteoritcal and Planetary Science, 43, 2059-2072. Poelchau M. H., Kenkmann T. and Kring D. A., 2009. Rim uplift and crater shape in Meteor Crater: the effects of target heterogeneities and trajectory obliquity. Journal of Geophysical Research, 114, E01006, doi:10.1029/2008JE003235. Kenkmann, T. -

A New Chronology for the Moon and Mercury

A new chronology for the Moon and Mercury Simone Marchi German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Planetary Research, Rutherfordstr. 2, D-12489 Berlin Dipartimento di Astronomia, Universit`adi Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 2, I-35122 Padova [email protected] Stefano Mottola German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Planetary Research, Rutherfordstr. 2, D-12489 Berlin Gabriele Cremonese INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 3, I-35122 Padova Matteo Massironi Dipartimento di Geoscienze, Universit`adi Padova, via Giotto 1, I-35137, Padova and Elena Martellato INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 3, I-35122 Padova ABSTRACT In this paper we present a new method for dating the surface of the Moon, obtained by modeling the incoming flux of impactors and converting it into a size distribution of resulting craters. We compare the results from this model with the standard chronology for the Moon showing their similarities and discrepancies. In particular, we find indications of a non-constant impactor flux in the last 500 Myr and also discuss the implications of our findings for the Late Heavy Bombardment hypothesis. We also show the potential of our model for accurate dating of other inner Solar System bodies, by applying it to Mercury. arXiv:0903.5137v1 [astro-ph.EP] 30 Mar 2009 Subject headings: solar system: general — planets and satellites: Earth, Mercury, Moon 1. Introduction the evolution of the Solar System and in particu- lar of our own planet, the Earth. Recently, thanks Craters are among the most spectacular surface to a fleet of new space missions (Mars Express features of the solid bodies of the Solar System. -

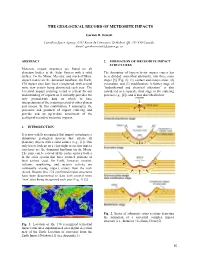

The Geological Record of Meteorite Impacts

THE GEOLOGICAL RECORD OF METEORITE IMPACTS Gordon R. Osinski Canadian Space Agency, 6767 Route de l'Aeroport, St-Hubert, QC J3Y 8Y9 Canada, Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT 2. FORMATION OF METEORITE IMPACT STRUCTURES Meteorite impact structures are found on all planetary bodies in the Solar System with a solid The formation of hypervelocity impact craters has surface. On the Moon, Mercury, and much of Mars, been divided, somewhat arbitrarily, into three main impact craters are the dominant landform. On Earth, stages [3] (Fig. 2): (1) contact and compression, (2) 174 impact sites have been recognized, with several excavation, and (3) modification. A further stage of more new craters being discovered each year. The “hydrothermal and chemical alteration” is also terrestrial impact cratering record is critical for our considered as a separate, final stage in the cratering understanding of impacts as it currently provides the process (e.g., [4]), and is also described below. only ground-truth data on which to base interpretations of the cratering record of other planets and moons. In this contribution, I summarize the processes and products of impact cratering and provide and an up-to-date assessment of the geological record of meteorite impacts. 1. INTRODUCTION It is now widely recognized that impact cratering is a ubiquitous geological process that affects all planetary objects with a solid surface (e.g., [1]). One only has to look up on a clear night to see that impact structures are the dominant landform on the Moon. The same can be said of all the rocky and icy bodies in the solar system that have retained portions of their earliest crust. -

Earth, Solar System, Milky

PAA Novice Astronomy Curriculum 1. An Introduction to Astronomy – June 7, 2019 Our Cosmic Address : Earth, Solar System, Milky Way, Local Group, Virgo Supercluster, Universe Overview of visible objects Sampling of exotic objects: black holes, dark energy, dark matter 2. Stars – September 6, 2019 Sun: birth, nuclear fusion, parts, Sun spots, atmosphere, space weather, death Colour & Temperature: OBAFGKM Size comparison: include link to YouTube video Distance H/R diagram Variable stars Life cycle of stars smaller and larger than our Sun Take Away: Plans to build a sundial 3. The Solar System – October 4, 2019 Sun and 8 planets: size (use scale model), distance (use scale model), physical characteristics Moons Origins of life Best possibilities of life in our solar system: Mars, Europa, Enceladus Dwarf Planets Comets Asteroids Meteoroid, Meteor, Meteorite 4. The Sun, Earth, Moon System – November 1, 2019 Day & Night Solar eclipse (use model) Lunar eclipse (use model) Lunar phases Influence of Moon on Earth: tides, stabilizing influence, retreating Seasons 5. The Moon – December 6, 2019 Birth: “Big Splat” Theory Evolution of Luna Historical exploration: Russian, American (Apollo 8-17) Current exploration: Chinese, ESA, etc. Discoveries: water ice, etc. Future? : Space station, habitation 6. The Electromagnetic Spectrum – January 3, 2020 Image of EMS Visible light 400-700 nm Infrared Microwave Radio Ultraviolet X-rays Gamma rays 7. Constellations-- -February 7, 2020 What is a constellation? What is an asterism? Historical significance: mythology (include story from more than Greek & Roman), agriculture, navigation and sea faring Seasonal Change Constellations as pointers 8. Eyepieces – March 6, 2020 eye relief 1 1/4” 2” Barlows Neutral Density filters Photographic filters Nebula filters: UHC, Skyglow, OIII, H alpha 9. -

LIST of ASTROBLEMS/IMPATC STRUCTURES IDENTIFIED on EARTH SURFACE Third Edition of the Geological Map of the World, Sheet 1 Physi

LIST OF ASTROBLEMS/IMPATC STRUCTURES IDENTIFIED ON EARTH SURFACE Third edition of the Geological Map of the World, sheet 1 Physiography, volcanoes, astroblemes, at 1:50 000 000 - Compilator: Philippe Bouysse, 2006 Sources: 1. (Roman type) Site: <http://www.unb.ca/passc/ImpactDatabase>, April 2006 By John Spray & Jason Hines, Planetary And Space Science Centre (PASSC) University of New Brunswick, Canada (174 structures: number 1 to 174), 2. (Italics) Site: <http://www.somerikko.net/old/geo/imp/impacts.htm>, April 2006 By Jarmo Moilanen (Finland): Impact Structures of the World (since Nov. 1996) (21 structures: a to u) 3. (Bold) In addition: Velingara (Master, Diallo, Kande, Wade, 1999, South Africa/Senegal), Iturralde (T. J. Killeen, Missouri Botanical Garden, Saint Louis, 1995-2006) astroblems and Gilf Kebir impact crater field (Paillou et al., C. R. Géoscience, Paris, vol. 335, 2003). (3 structures) 4. (In red) Tunguska airblast TOTAL: 198 IMPACT STRUCTURES Nota: * = approximate central position DIAMETER N° CRATER NAME LOCATION LATITUDE LONGITUDE Age (Ma)* EXPOSED DRILLED (km) South Australia, 1 Acraman Australia S 32° 1' E 135° 27' 90 ~ 590 Y N a Alamo USA N 37°30' W 116°30' 190 367 - - 2 Ames Oklahoma, U.S.A. N 36° 15' W 98° 12' 16 470 ± 30 N Y 3 Amelia Creek Australia S 20° 55' E 134 ° 50' ~20 1640 - 600 Y N 4 Amguid Algeria N 26° 5' E 4° 23' 0.45 < 0.1 Y N 5 Aorounga Chad, Africa N 19° 6' E 19° 15' 12.6 < 345 Y N 6 Aouelloul Mauritania N 20° 15' W 12° 41' 0.39 3.0 ± 0.3 Y N 7 Araguainha Brazil S 16° 47' W 52° 59' 40 244.40 ± 3.25 Y N 8 Arkenu 1 Libya N 22° 4' E 23° 45' 6.8 < 140 Y N 9 Arkenu 2 Libya N 22° 4' E 23° 45' 10,3 < 140 Y N 10 Avak Alaska, U.S.A. -

Terrestrial Impact Structures- a Bibliography 1965-68

Terrestrial Impact Structures- A Bibliography 1965-68 By JACQUELYN H. FREEBERG GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1320 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1969 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director Library of Congress catalog-card No. 74-650225 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 30 cents paper cover CONTENTS Page Abstract--------------------------------------------------------- 1 Introduction______________________________________________________ 1 Seria~----------------------------------------------------------- 2 Bibliography______________________________________________________ 3· Distribution and general characteristics of impact structures_________ 3: Impact sites___________________________________________________ 12: Agnak Island Oraters _ _ __ _ __ _ __ __ _ __ __ _ _ _ __ __ _ _ __ _ _ _ __ _ _ _ __ 1Z Aouelloul Crater___________________________________________ 12 Arn Valley Craters________________________________________ 12 Barringer Crater__________________________________________ 12 Bass Strait_______________________________________________ 13 Boxhole Crater____________________________________________ 14 Brent Crater______________________________________________ 14 Butare Crater_______________________________________ ------ 14 Campo del Cielo Craters----------------------------------- 14 Carswell Lake structure _________________________ . _ _ _ __ _ _ __ _ 15 Chassenon -

Australian Aboriginal Geomythology: Eyewitness Accounts of Cosmic Impacts?

Preprint: Submitted to Archaeoastronomy – The Journal of Astronomy in Culture Australian Aboriginal Geomythology: Eyewitness Accounts of Cosmic Impacts? Duane W. Hamacher1 and Ray P. Norris2 Abstract Descriptions of cosmic impacts and meteorite falls are found throughout Australian Aboriginal oral traditions. In some cases, these texts describe the impact event in detail, suggesting that the events were witnessed, sometimes citing the location. We explore whether cosmic impacts and meteorite falls may have been witnessed by Aboriginal Australians and incorporated into their oral traditions. We discuss the complications and bias in recording and analysing oral texts but suggest that these texts may be used both to locate new impact structures or meteorites and model observed impact events. We find that, while detailed Aboriginal descriptions of cosmic impacts and meteorite falls are abundant in the literature, there is currently no physical evidence connecting any of these accounts to impact events currently known to Western science. Notice to Aboriginal Readers This paper gives the names of, or references to, Aboriginal people that have passed away throughout, and to information that may be considered sacred to some groups. It also contains information published in Nomads of the Australian Desert by Charles P. Mountford (1976). This book was banned from sale in the Northern Territory in 1976 as it contained sacred/secret knowledge of the Pitjantjatjara (see Brown 2004:33-35; Neate 1982). No information about the Pitjantjatjara from Mountford’s book is presented in this paper. 1 Department of Indigenous Studies, Macquarie University, NSW, 2109, Australia [email protected] | Office: (+61) 2 9850 8671 Duane Hamacher is a PhD candidate in the Department of Indigenous Studies at Macquarie University in Sydney, Australia. -

Science Article on Fast-Breaking Items Or Current Topics of General Inter- Some Errors

Vol. 5, No. 10 October 1995 INSIDE • Aerial Photos by Washburn, p. 200 • Call for Award Nominations, p. 203 • Rocky Mountain Section Meeting, GSA TODAY p. 206 A Publication of the Geological Society of America • Cordilleran Section Meeting, p. 207 Figure 2. Topography of the Manicouagan complex impact The Record of Terrestrial structure, Quebec, Canada. The original diameter of this Impact Cratering 214 ± 1 Ma structure is esti- mated to have been 100 km. Richard Grieve, James Rupert, Janice Smith, Ann Therriault Erosion, however, has removed the rim, and the structure Continental Geoscience Division. Geological Survey of Canada appears as a series of circular Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0Y3, Canada features with positive and nega- tive relief, beginning with a 150-km-diameter outer fracture zone, seen most easily in the western and southern sectors, ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION and culminating in slightly off- center topographic peaks. The Approximately 150 terrestrial The first studies of a terrestrial annular Manicouagan reservoir impact structures are currently impact structure, of the now famous (dark green area slightly left of known, representing a small, biased Meteor or Barringer Crater, Arizona, in center) is ˜65 km in diameter sample of a much larger population. the early 1900s by D. M. Barringer and and at ˜360 m elevation. Eleva- The spatial distribution indicates colleagues, produced more controversy tions in the center are as much as 1100 m (brown). concentrations in cratonic areas— than acceptance. There was, however, a ˜ in particular, ones where there have gradual increase in the number of rec- been active search programs. The ognized small craters with meteorite majority of the known impact struc- fragments until the 1960s, when so- tures are <200 m.y. -

Subsurface of Overburden for Possible Meteorite Impact Crater at Bukit Bunuh, Malaysia Using 2-D Electrical Resistivity Imaging

Subsurface of Overburden for Possible Meteorite Impact Crater at Bukit Bunuh, Malaysia using 2-D Electrical Resistivity Imaging Mark Jinmin Postgradute Student, Geophysics Section, School of Physics, 11800 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia e-mail: [email protected] Dr. Rosli Saad Senior Lecturer Geophysics Section, School of Physics, 11800 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia e-mail:[email protected] Dr. M. Mokhtar Saidin Assoc. Prof., Centre for Global Archeological Research Malaysia, 11800 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia e-mail:[email protected] Y.C. Kiu Postgradute Student, Geophysics Section, School of Physics, 11800 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia e-mail: [email protected] Nur Azwin Ismail Postgradute Student, Geophysics Section, School of Physics, 11800 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Bukit Bunuh is situated in Lengggong, Perak one of Peninsular Malaysia’s most important areas for archeology that revealed many traces of Malaysia’s prehistory. Geophysical method especially 2-D resistivity imaging method is non-destructive which applied in geo-subsurface study for meteorite impact. The study consists of three stages that are regional study and detail study. Total of fourteen survey lines, which include parallel to Sungai Perak and two mountains ranges, Bintang Range and Titiwangsa Range. Survey lines were executed using Pole-dipole array with 5 m minimum electrode spacing. From every stage, the results show the area consists of two main layers which are alluvium and granitic bedrock. The first zone is alluvium with boulders with resistivity value of 10-800 Ωm while the second zone is granitic bedrock with resistivity value of >1500 Ωm. -

The Central Uplift of Spider Crater, Western Australia

Large Meteorite Impacts and Planetary Evolution V (2013) 3025.pdf THE CENTRAL UPLIFT OF SPIDER CRATER, WESTERN AUSTRALIA. T. Kenkmann1 and M. H. Poelchau1, 1Institute of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Albert-Ludwigs Universität Freiburg, Albertstraße 23-B, 79104 Freiburg, Germany, [email protected]. Introduction: The Spider impact crater, Australia (13 Macrostructures and kinematic model: The central x 11 km Ø, N16°44’27’’, E126°05’21’’) named after uplift consists of two imbricate thrust stacks that sur- the peculiar appearance of its central uplift, is situated round the core of the structure, indicating N-S shorten- on the Kimberley-Plateau in Western Australia. J. E. ing with a preferred material transport top to southerly Harms was the first who recognized the structure direction (Fig. 1). Dipping of beds within the imbricate around 1960, but twenty years later a cryptovolcanic stacks ranges between 20-80° (40° mean dip) and origin was still favored [1]. Shoemaker and Shoemaker shows no systematic change from N to S. The traces of [2, 3] mapped the site in 1984-85. McHone [4, 5] and each thrust are bent and their strike gradually shifts Abels [6, 7] investigated the structure by means of from N to S. To explain the change in orientation of remote sensing analyses. While most authors favored the thrust slices from up range to downrange a very an oblique impact from N to NW to explain the nor- simple approach of vector summation in a horizontal therly dipping thrust stacks [2, 3], Abels [6, 7] argued plane might be helpful: An idealized flow field during that pre-impact topography and the (very) gently dip- crater collapse at a vertical incidence is represented by ping limbs of the broad Mt.