Trypanosome Infection Rates in Tsetse Flies in the “Silent” Sleeping Sickness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of the Evolution of Insecticide Resistance in Main Malaria Vectors in Cameroon from 1990 to 2017 Christophe Antonio-Nkondjio1,5*, N

Antonio-Nkondjio et al. Parasites & Vectors (2017) 10:472 DOI 10.1186/s13071-017-2417-9 REVIEW Open Access Review of the evolution of insecticide resistance in main malaria vectors in Cameroon from 1990 to 2017 Christophe Antonio-Nkondjio1,5*, N. Sonhafouo-Chiana2, C. S. Ngadjeu3, P. Doumbe-Belisse3, A. Talipouo3, L. Djamouko-Djonkam4, E. Kopya3, R. Bamou4, P. Awono-Ambene1 and Charles S. Wondji5 Abstract Background: Malaria remains a major public health threat in Cameroon and disease prevention is facing strong challenges due to the rapid expansion of insecticide resistance in vector populations. The present review presents an overview of published data on insecticide resistance in the main malaria vectors in Cameroon to assist in the elaboration of future and sustainable resistance management strategies. Methods: A systematic search on mosquito susceptibility to insecticides and insecticide resistance in malaria vectors in Cameroon was conducted using online bibliographic databases including PubMed, Google and Google Scholar. From each peer-reviewed paper, information on the year of the study, mosquito species, susceptibility levels, location, insecticides, data source and resistance mechanisms were extracted and inserted in a Microsoft Excel datasheet. The data collected were then analysed for assessing insecticide resistance evolution. Results: Thirty-three scientific publications were selected for the analysis. The rapid evolution of insecticide resistance across the country was reported from 2000 onward. Insecticide resistance was highly prevalent in both An. gambiae (s.l.) and An. funestus. DDT, permethrin, deltamethrin and bendiocarb appeared as the most affected compounds by resistance. From 2000 to 2017 a steady increase in the prevalence of kdr allele frequency was noted in almost all sites in An. -

GEF Prodoc TRI Cameroon 28 02 18

International Union for the Conservation of Nature Country: Cameroon PROJECT DOCUMENT Project Title: Supporting Landscape Restoration and Sustainable Use of local plant species and tree products (Bambusa ssp, Irvingia spp, etc) for Biodiversity Conservation, Sustainable Livelihoods and Emissions Reduction in Cameroon BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT The Republic of Cameroon has a diverse ecological landscape, earning her the title “Africa in Miniature”. The southern portions of Cameroon’s forests are part of the Congo Basin forest ecosystem, the second largest remaining contiguous block of rainforest on Earth, after the Amazon. In addition to extensive Mangrove belts, Cameroon also holds significant portions of the Lower Guinea Forest Ecosystems and zones of endemism extending into densely settled portions of the Western Highlands and Montagne forests. The North of the country comprising the Dry Sudano-Sahelian Savannah Zones is rich in wildlife, and home to dense human and livestock populations. Much of the population residing in these areas lives in extreme poverty. This diversity in biomes makes Cameroon one of the most important and unique hotspots for biodiversity in Africa. However, human population growth, migrations, livelihoods strategies, rudimentary technologies and unsustainable land use for agriculture and small-scale forestry, energy and livestock, are contributing to biodiversity loss and landscape degradation in Cameroon. Despite strong institutional frameworks, forest and environmental policies/legislation, and a human resource capital, Cameroon’s network of biomes that include all types of forests, tree-systems, savannahs, agricultural mosaics, drylands, etc., are progresively confronted by various forms of degradation. Degradation, which is progressive loss of ecosystem functions (food sources, water quality and availability, biodversity, soil fertility, etc), now threatens the livelihoods of millions of Cameroonians, especially vulnerable groups like women, children and indigenous populations. -

Centre Region Classifications

Centre Region Classifications Considering the World Bank list of economies (June 2020) OTHM centres have been classified into three separate regions: • Region 1: High income economies; • Region 2: Upper middle income economies; and • Region 3: Lower middle income and low income economies. Centres in the United Kingdom falls into Region 1 along with other high-income economies – (normal fees apply for all Region 1 Centres). Prospective centres and learners should visit www.othm.org.uk to find which region their centre falls into and pay the appropriate fees. Economy Income group Centre class Afghanistan Low income Region 3 Albania Upper middle income Region 2 Algeria Lower middle income Region 3 American Samoa Upper middle income Region 2 Andorra High income Region 1 Angola Lower middle income Region 3 Antigua and Barbuda High income Region 1 Argentina Upper middle income Region 2 Armenia Upper middle income Region 2 Aruba High income Region 1 Australia High income Region 1 Austria High income Region 1 Azerbaijan Upper middle income Region 2 Bahamas, The High income Region 1 Bahrain High income Region 1 Bangladesh Lower middle income Region 3 Barbados High income Region 1 Belarus Upper middle income Region 2 Belgium High income Region 1 Belize Upper middle income Region 2 Benin Lower middle income Region 3 Bermuda High income Region 1 Bhutan Lower middle income Region 3 Bolivia Lower middle income Region 3 Bosnia and Herzegovina Upper middle income Region 2 Botswana Upper middle income Region 2 Brazil Upper middle income Region 2 British -

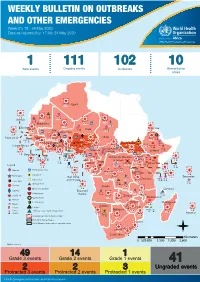

WEEKLY BULLETIN on OUTBREAKS and OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 21: 18 - 24 May 2020 Data As Reported By: 17:00; 24 May 2020

WEEKLY BULLETIN ON OUTBREAKS AND OTHER EMERGENCIES Week 21: 18 - 24 May 2020 Data as reported by: 17:00; 24 May 2020 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR Africa WHO Health Emergencies Programme 1 111 102 10 New events Ongoing events Outbreaks Humanitarian crises 8 306 600 Algeria 25 1 1 0 485 0 237 6 Gambia 7 0 675 60 945 61 Mauritania 13 0 1 030 65 Senegal 304 1 39 0Eritrea 3 047 35 Niger 7 635 37 Mali 380 3 Burkina Faso 95 4 0 3 7 0 Cabo Verdé Guinea 832 52 22 0 Chad 582 5 4 690 18 4 1 7 839 226 29 0 Nigeria 3 275 20Côte d’Ivoire South Sudan 1 873 895 15 604 1 274 3 32 0 Guinea-Bissau Ghana 987 202 4 400 159 7 551 92 381 12 139 0 2 0 4 0 Central African 25 0 Liberia 2 376 30 22 0 655 8 Benin Cameroon 4 732 26 Ethiopia 1 173 6 6 683 32 Republic 1 618 5 21 219 83 Sierra léone Togo 352 14 1 449 71 Uganda 120 18 Democratic Republic 812 3 339 3 14 0 401 3 1 214 51 of Congo 8 4 202 0 505 32 1 1 Congo 304 0 Gabon 3 463 2 280 Kenya 149 3 555 13 Legend 265 26 9 0 95 4 37 0 1 934 12 58 112 748 Rwanda Measles Humanitarian crisis 327 0 487 16 9 018 112 Burundi 299 9 11 0 Hepatitis E Monkeypox 42 1 2 305 66 Seychelles Sao Tome 5 0 Yellow fever Tanzania 857 0 70 0 Lassa fever and Principe 509 21 20 7 79 0 Dengue fever Cholera 1 441 37 1 043 12 Angola Ebola virus disease Comoros cVDPV2 Equatorial 83 4 2 0 Chikungunya Guinea 121 0 696 0 COVID-19 Malawi 69 4 Zambia Mozambique Guinea Worm 920 7 Anthrax Leishmaniasis Zimbabwe 2 305 18 Madagascar Malaria Namibia Floods Plague 286 1 Botswana 56 4 334 10 Cases Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever 236 865 226 527 2 Deaths 21 -

CAMEROON Education Environment, Water and Sanitation HIV/AIDS Project Income-Generating Activities

Health Child protection CAMEROON Education Environment, water and sanitation HIV/AIDS project Income-generating activities March 2012 – February 2015 Project overview OBJECTIVE Prevention, comprehensive care and promotion of the rights of the most vulnerable against HIV/AIDS in the health district of Okola, in the Centre Region. Project funded by the Région Ile de France and the city of Paris CONTEXT HIV/AIDS in Cameroon The 2/3 of the HIV positive people in the world live in the Sub-Saharan Africa. In Cameroon, it is estimated that they are 550,000, to which 300,000 HIV orphans must be added. The Centre is one of the most affected Region (out of the 10 Regions composing the country), as it accounts for 20% of the national HIV positive population. The most vulnerable people to the epidemic are : - Women, who for biological and social reasons (less control on their sexuality than men), make up 2/3 of the HIV positive persons in the country, -Young people (amongst the 60,000 affected people each year, half of them is from 15 to 24). The infection level is mainly due to the lack of information about HIV/AIDS. It implies a low condom use in Cameroon, while it is the most effective way to prevent HIV/AIDS. The access to HIV testing is also lacking: in 2004, 80% of women and about 90% of men in the area had never been tested for HIV. The comprehensive care services (therapeutic, psychosocial, economic support, etc.) for people living with HIV are rare, not to say missing in many rural areas. -

Cholera Outbreak

Emergency appeal final report Cameroon: Cholera outbreak Emergency appeal n° MDRCM011 GLIDE n° EP-2011-000034-CMR 31 October 2012 Period covered by this Final Report: 04 April 2011 to 30 June 2012 Appeal target (current): CHF 1,361,331. Appeal coverage: 21%; <click here to go directly to the final financial report, or here to view the contact details> Appeal history: This Emergency Appeal was initially launched on 04 April 2011 for CHF 1,249,847 for 12 months to assist 87,500 beneficiaries. CHF 150,000 was initially allocated from the Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Fund (DREF) to support the national society in responding by delivering assistance. Operations update No 1 was issued on 30 May 2011 to revise the objectives and budget of the operation. Operations update No 2 was issued on 31st May 2011 to provide financial statement against revised budget. Operations update No 3 was issued on 12 October 2011 to summarize the achievements 6 months into the operation. Operations update No 4 was issued on 29 February 2012 to extend the timeframe of the operation from 31st March to 30 June 2012 to cover the funding agreement with the American Embassy in Cameroon. PBR No M1111087 was submitted as final report of this operation to the American Embassy in Cameroon on 03 August 2012. Throughout the operation, Cameroon Red Cross volunteers sensitized the populations on PBR No M1111127 was submitted as final report of this how to avoid cholera. Photo/IFRC operation to the British Red Cross on 14 August 2012. Summary: A serious cholera epidemic affected Cameroon since 2010. -

Land Use and Land Cover Changes in the Centre Region of Cameroon

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 18 February 2020 Land Use and Land Cover changes in the Centre Region of Cameroon Tchindjang Mesmin; Saha Frédéric, Voundi Eric, Mbevo Fendoung Philippes, Ngo Makak Rose, Issan Ismaël and Tchoumbou Frédéric Sédric * Correspondence: Tchindjang Mesmin, Lecturer, University of Yaoundé 1 and scientific Coordinator of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Saha Frédéric, PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and project manager of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Voundi Eric, PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and technical manager of Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring [email protected] Mbevo Fendoung Philippes PhD student of the University of Yaoundé 1 and internship at University of Liège Belgium; [email protected] Ngo Makak Rose, MSC, GIS and remote sensing specialist at Global Mapping and Environmental Monitoring; [email protected] Issan Ismaël, MSC and GIS specialist, [email protected] Tchoumbou Kemeni Frédéric Sédric MSC, database specialist, [email protected] Abstract: Cameroon territory is experiencing significant land use and land cover (LULC) changes since its independence in 1960. But the main relevant impacts are recorded since 1990 due to intensification of agricultural activities and urbanization. LULC effects and dynamics vary from one region to another according to the type of vegetation cover and activities. Using remote sensing, GIS and subsidiary data, this paper attempted to model the land use and land cover (LULC) change in the Centre Region of Cameroon that host Yaoundé metropolis. The rapid expansion of the city of Yaoundé drives to the land conversion with farmland intensification and forest depletion accelerating the rate at which land use and land cover (LULC) transformations take place. -

Predicted Distribution and Burden of Podoconiosis in Cameroon

Predicted distribution and burden of podoconiosis in Cameroon. Supplementary file Text 1S. Formulation and validation of geostatistical model of podoconiosis prevalence Let Yi denote the number of positively tested podoconiosis cases at location xi out of ni sample individuals. We then assume that, conditionally on a zero-mean spatial Gaussian process S(x), the Yi are mutually independent Binomial variables with probability of testing positive p(xi) such that ( ) = + ( ) + ( ) + ( ) + ( ) + ( ) 1 ( ) � � 0 1 2 3 4 5 − + ( ) + ( ) 6 where the explanatory in the above equation are, in order, fraction of clay, distance (in meters) to stable light (DSTL), distance to water bodies (DSTW), elevation (E), precipitation(Prec) (in mm) and fraction of silt at location xi. We model the Gaussian process S(x) using an isotropic and stationary exponential covariance function given by { ( ), ( )} = { || ||/ } 2 ′ − − ′ Where || ||is the Euclidean distance between x and x’, is the variance of S(x) and 2 is a scale − pa′rameter that regulates how fast the spatial correlation decays to zero for increasing distance. To check the validity of the adopted exponential correlation function for the spatial random effects S(x), we carry out the following Monte Carlo algorithm. 1. Simulate a binomial geostatistical data-set at observed locations xi by plugging-in the maximum likelihood estimates from the fitted model. 2. Estimate the unstructured random effects Zi from a non-spatial binomial mixed model obtained by setting S(x) =0 for all locations x. 3. Use the estimates for Zi from the previous step to compute the empirical variogram. 4. Repeat steps 1 to 3 for 10,000 times. -

Forecasts and Dekadal Climate Alerts for the Period 1St to 10Th June 2021

REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON Paix-Travail-Patrie Peace-Work-Fatherland ----------- ----------- OBSERVATOIRE NATIONAL SUR NATIONAL OBSERVATORY LES CHANGEMENTS CLIMATIQUES ON CLIMATE CHANGE ----------------- ----------------- DIRECTION GENERALE DIRECTORATE GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- ONACC www.onacc.cm; [email protected]; Tel : (+237) 693 370 504 / 654 392 529 BULLETIN N° 82 Forecasts and Dekadal Climate Alerts for the Period 1st to 10th June 2021 st 1 June 2021 © NOCC June 2021, all rights reserved Supervision Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Eng. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC). Production Team (NOCC) Prof. Dr. Eng. AMOUGOU Joseph Armathé, Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC) and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Yaounde I, Cameroon. Eng. FORGHAB Patrick MBOMBA, Deputy Director General, National Observatory on Climate Change (NOCC). BATHA Romain Armand Soleil, PhD student and Technical staff, NOCC. ZOUH TEM Isabella, M.Sc. in GIS-Environment and Technical staff, NOCC. NDJELA MBEIH Gaston Evarice, M.Sc. in Economics and Environmental Management. MEYONG René Ramsès, M.Sc. in Physical Geography (Climatology/Biogeography). ANYE Victorine Ambo, Administrative staff, NOCC. ELONG Julien Aymar, M.Sc. in Business and Environmental law. I. Introduction -

Upstream Nachtigal Hydroelectric Project

Upstream Nachtigal Hydroelectric Project S U M M A R Y O F ENVIRONMENTAL A N D SOCIAL ACTION PLANS : - E NVIRONNEMENTAL A ND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN , - L IVELIHOOD RESTORATIO N P L A N FOR SAND MINING WO RKERS , - R ESETTLEMENT AND COMP ENSATION ACTIONS PLA NS, - L O C A L E C O N O M I C DEVELOPMENT ACTION PLAN . 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF THE ESMP The Nachtigal Project (the "Project") is to design, build and operate during the concession period (35 years) a reservoir and hydroelectric plant on the Sanaga River around the upstream Nachtigal Falls (located some 65 km north-east of Yaoundé) and a transmission line of 50 km of 225 kV in technical terms up to Nyom2 (north of Yaoundé). The total planned capacity to be installed is 420 MW, with 7 generators with an electric power unit of 60 MW, corresponding to 980 m3/s of design flow. The Project is developed by 3 partners (the State of Cameroon, EDF, IFC) under a joint development agreement signed on 8 November 2013. Construction is expected to start in 2018 and the operational implementation will spread out from 2021 to 2022. The project will engender relatively moderate environmental and social impacts as a run-of-river facility with the creation of a low surface reservoir. The main potential social impacts of the Project are: Physical and economic displacement due to the Project’s influence and its impact on: - Residential houses, - Farmlands where cash crops and vegetable crops are cultivated - Fishing grounds: - that will disappear at the level of the Nachtigal Upstream rapids through -

Agro-Industrial Investments in Cameroon Large-Scale Land Acquisitions Since 2005

Agro-industrial investments in Cameroon Large-scale land acquisitions since 2005 Samuel Nguiffo and Michelle Sonkoue Watio Land, Investment and Rights As pressures on land and natural resources increase, disadvantaged groups risk losing out, particularly where their rights are insecure, their capacity to assert these rights is limited, and major power imbalances shape relations with government and incoming investors. IIED’s Land, Investment and Rights series generates evidence around changing pressures on land, multiple investment models, applicable legal frameworks and ways for people to claim rights. Other reports in the Land, Investment and Rights series can be downloaded from www.iied.org/pubs. Recent titles include: • Understanding agricultural investment chains: Lessons to improve governance. 2014. Cotula et al. • Accountability in Africa’s land rush: what role for legal empowerment. 2013. Polack et al. Also available in French. • Long-term outcomes of agricultural investments: Lessons from Zambia. 2012. Mujenja and Wonani. • Agricultural investments and land acquisitions in Mali: Context, trends and case studies. 2013. Djiré et al. Also available in French. • Joint ventures in agriculture: Lessons from land reform projects in South Africa. 2012. Lahiff et al. Also available in French. Under IIED’s Legal Tools for Citizen Empowerment programme, we also share lessons from the innovative approaches taken by citizens’ groups to claim rights, from grassroots action and engaging in legal reform, to mobilising international human rights bodies and making use of grievance mechanisms, through to scrutinising international investment treaties, contracts and arbitration. Lessons by practitioners are available on our website at www.iied.org/pubs. Recent reports include: • Walking with villagers: How Liberia’s Land Rights Policy was shaped from the grassroots. -

Spatial Relationships Between Dominant Ants and the Cocoa Mirid Sahlbergella Singularis in Traditional Cocoa-Based Agroforestry Systems

SPATIAL RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN DOMINANT ANTS AND THE COCOA MIRID SAHLBERGELLA SINGULARIS IN TRADITIONAL COCOA-BASED AGROFORESTRY SYSTEMS Régis Babin1*, Cyril Piou1, Yédé2,3, Zéphirin Tadu2, Raymond Mahob2,3, G. Martijn ten Hoopen1,3, Leila Bagny Beilhe1,3, Champlain Djiéto-Lordon2 1 CIRAD, UPR Bioagresseurs analyse et maîtrise du risque, F-34398 Montpellier, France 2 University of Yaoundé I, Faculty of Sciences, P.O Box 812 Yaoundé, Cameroon 3 IRAD, P.O Box 2067 Yaoundé, Cameroon * Corresponding author: [email protected] SUMMARY Manipulating ant communities to control pests of cocoa has proven to be a promising strategy, especially in Asia. However, concerning African cocoa mirids, the main pests of cocoa in Africa, basic knowledge on mirid-ant relationships is still incomplete. Our study aimed to characterize the spatial relationships between dominant ant species and the mirid Sahlbergella singularis (Hemiptera: Miridae) in traditional cocoa-based agroforestry systems of Cameroon. Over two consecutive years, mirid and ant populations were assessed by a chemical knock-down sampling method in four plots of 100 cocoa trees, located in three different agroecological zones in the Centre region of Cameroon. Mapping procedures were used to display spatial distribution of mirid and ant populations. Also, we adapted spatial statistics methodologies of point pattern analysis to consider the regular tree position effects on insect positions. These techniques allow testing the statistical significance of Poisson null models, leading to the classification of the spatial patterns of insects into association vs. segregation. Our results clearly demonstrated spatial segregation between mirid and the dominant weaver ant Oecophylla longinoda, known as a key-predator in natural ecosystems.