Analysis Selection for JCC January 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Please Copy and Paste the Following Text Into Your E-Mail

Please copy and paste the following text into your e-mail To: UN Human Rights Council Member States’ foreign ministers and their country missions in Geneva On 1 February, the Myanmar military seized power in a military coup d'etat and arbitrarily detained President Win Myint, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and other civilian leaders. A year-long state of emergency was declared, installing Vice-President and former lieutenant- general Myint Swe as the acting President, who immediately handed over power to commander- in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. The coup has been met with nationwide peaceful demonstrations by the people of Myanmar demanding that the Military respects the outcomes of the November 2020 elections, restores the elected civilian government and releases all those who are arbitrarily detained, and that the Military be held accountable for its atrocities. The junta has responded to these protests with systematic and violent crackdowns. The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar has described the junta’s crackdown on peaceful protestors as crimes against humanity. Since the coup, over 755 people, including at least 43 children, women and medical workers have been killed so far in the junta’s violence. Also, over 4,496 people, including human rights defenders and journalists documenting the military’s atrocities, civil society and political activists, and civilian political leaders have been arbitrarily arrested and detained and raided their offices and homes. Whereabouts of many who have been arrested remain unknown while several others have reported torture, sexual violence and ill treatment in detention. -

India-Myanmar Joint Statement During State Visit of President to Myanmar (10-14 December 2018)

Media Center Media Center India-Myanmar Joint Statement during State Visit of President to Myanmar (10-14 December 2018) December 13, 2018 1. At the invitation of the President of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, His Excellency U Win Myint and the First Lady Daw Cho Cho, the President of the Republic of India, His Excellency Shri Ram Nath Kovind and the First Lady Smt. Savita Kovind paid a State Visit to Myanmar from 10 to 14 December 2018. The visit reinforces the tradition of high-level interaction between the leaders of the two countries in recent years. 2. A ceremonial welcome was accorded to President Kovind at the Presidential Palace in Nay Pyi Taw on 11 December, 2018. President U Win Myint and President Kovind held a bilateral meeting and President U Win Myint hosted a State Banquet for the visiting President in his honour. President Kovind also met with State Counsellor, Her Excellency Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. The discussions between the leaders were held in a cordial and constructive atmosphere that is the hallmark of the close and friendly relations between the two countries. President U Win Myint and President Kovind also witnessed the signing of MoUs between the two sides in the areas of judicial and educational cooperation. The Indian side also handed over the first 50 units of prefabricated houses built in Rakhine State under the Rakhine State Development Programme funded by the Government of India. Furthermore, both sides agreed to sign at the earliest the MoU for Cooperation on Combating Timber Trafficking and Conservation of Tigers and Other Wildlife and the MoU on Bilateral Cooperation for Prevention of Trafficking in Persons; Rescue, Recovery, Repatriation and Re-integration of Victims of Trafficking, on which negotiations are nearing completion. -

New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State?

CRS INSIGHT New Crisis Brewing in Burma's Rakhine State? February 15, 2019 (IN11046) | Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) Approximately 250 Chin and Rakhine refugees entered into Bangladesh's Bandarban district in the first week of February, trying to escape the fighting between Burma's military, or Tatmadaw, and one of Burma's newest ethnic armed organizations (EAOs), the Arakan Army (AA). Bangladesh's Foreign Minister Abdul Momen summoned Burma's ambassador Lwin Oo to protest the arrival of the Rakhine refugees and the military clampdown in Rakhine State. Bangladesh has reportedly closed its border to Rakhine State. U.N. Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in Myanmar Yanghee Lee released a press statement on January 18, 2019, indicating that heavy fighting between the AA and the Tatmadaw had displaced at least 5,000 people. She also called on the Rakhine State government to reinstate the access for international humanitarian organizations. The Conflict Between the Arakan Army and the Tatmadaw The AA was formed in Kachin State in 2009, with the support of the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). In 2015, the AA moved some of its soldiers from Kachin State to southwestern Chin State, and began attacking Tatmadaw security bases in Chin State and northern Rakhine State (see Figure 1). In late 2017, the AA shifted more of its operations into northeastern Rakhine State. According to some estimates, the AA has approximately 3,000 soldiers based in Chin and Rakhine States. Figure 1. Reported Clashes between Arakan Army and Tatmadaw Source: CRS, utilizing data provided by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED). -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 20 August 2001

United Nations A/56/312 General Assembly Distr.: General 20 August 2001 Original: English Fifty-sixth session Item 131 (c) of the provisional agenda* Human rights questions: human rights situations and reports of special rapporteurs and representatives Situation of human rights in Myanmar Note by the Secretary-General** The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the members of the General Assembly, the interim report prepared by Paulo Sergio Pinheiro, Special Rapporteur of the Commission on Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, in accordance with Commission resolution 2001/15 and Economic and Social Council decision 2001/251. * A/56/150. ** In accordance with General Assembly resolution 54/248, sect. C, para. 1, this report is being submitted on 20 August 2001 so as to include as much updated information as possible. 01-51752 (E) 260901 *0151752* A/56/312 Interim report of the Special Rapporteur of the Commission on Human Rights on the situation of human rights in Myanmar Summary The present report is the first report of the present Special Rapporteur, appointed to this mandate on 28 December 2000. The report refers to his activities and developments relating to the situation of human rights in Myanmar between 1 January and 14 August 2001. In view of the brevity and exploratory nature of the Special Rapporteur’s initial visit to Myanmar in April and pending a proper fact-finding mission to take place at the end of September 2001, this report addresses only a limited number of areas. In the Special Rapporteur’s assessment as presented in this report, political transition in Myanmar is a work in progress and, as in many countries, to move ahead incrementally will be a complex process. -

Acts Adopted Under Title V of the Treaty on European Union)

L 108/88EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2005 (Acts adopted under Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2005/340/CFSP of 25 April 2005 extending restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Common Position 2004/423/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, (8) In the event of a substantial improvement in the overall political situation in Burma/Myanmar, the suspension of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in these restrictive measures and a gradual resumption of particular Article 15 thereof, cooperation with Burma/Myanmar will be considered, after the Council has assessed developments. Whereas: (9) Action by the Community is needed in order to (1) On 26 April 2004, the Council adopted Common implement some of these measures, Position 2004/423/CFSP renewing restrictive measures 1 against Burma/Myanmar ( ). HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: (2) On 25 October 2004, the Council adopted Common Position 2004/730/CFSP on additional restrictive Article 1 measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Annexes I and II to Common Position 2004/423/CFSP shall be Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (2). replaced by Annexes I and II to this Common Position. (3) On 21 February 2005, the Council adopted Common Position 2005/149/CFSP amending Annex II to Article 2 Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (3). Common Position 2004/423/CFSP is hereby renewed for a period of 12 months. (4) The Council would recall its position on the political situation in Burma/Myanmar and considers that recent developments do not justify suspension of the restrictive Article 3 measures. -

The Generals Loosen Their Grip

The Generals Loosen Their Grip Mary Callahan Journal of Democracy, Volume 23, Number 4, October 2012, pp. 120-131 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/jod.2012.0072 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jod/summary/v023/23.4.callahan.html Access provided by Stanford University (9 Jul 2013 18:03 GMT) The Opening in Burma the generals loosen their grip Mary Callahan Mary Callahan is associate professor in the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. She is the author of Making Enemies: War and State Building in Burma (2003) and Political Authority in Burma’s Ethnic Minority States: Devolution, Occupation and Coexistence (2007). Burma1 is in the midst of a political transition whose contours suggest that the country’s political future is “up for grabs” to a greater degree than has been so for at least the last half-century. Direct rule by the mili- tary as an institution is over, at least for now. Although there has been no major shift in the characteristics of those who hold top government posts (they remain male, ethnically Burman, retired or active-duty mili- tary officers), there exists a new political fluidity that has changed how they rule. Quite unexpectedly, the last eighteen months have seen the retrenchment of the military’s prerogatives under decades-old draconian “national-security” mandates as well as the emergence of a realm of open political life that is no longer considered ipso facto nation-threat- ening. Leaders of the Tatmadaw (Defense Services) have defined and con- trolled the process. -

Myanmar Military Should End Its Use of Violence and Respect Democracy

2021-02-01 MYANMAR MILITARY SHOULD END ITS USE OF VIOLENCE AND RESPECT DEMOCRACY The undersigned groups today denounced an apparent coup in Myanmar, and associated violence, which has suspended civilian government and effectively returned full power to the military. On 1 February, the military arbitrarily detained State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and other leaders of the National League for Democracy. A year-long state of emergency was declared, installing Vice-President and former lieutenant-general Myint Swe as the acting President. Myint Swe immediately handed over power to commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing (Section 418 of Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution enables transfer of legislative, executive, and judicial powers to the Commander in Chief). Internet connections and phone lines throughout the country were disrupted, pro-democracy activists have been arbitrarily arrested, with incoming reports of increased detentions. Soldiers in armoured cars have been visibly roaming Naypyitaw and Yangon, raising fears of lethal violence. “The military should immediately and unconditionally release all detained and return to Parliament to reach a peaceful resolution with all relevant parties,” said the groups. The military and its aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) had disputed the results of the November elections, which saw the majority of the seats won by the NLD. The arrests of the leaders came just before the Parliament was due to convene for the first time in order to pick the President and Vice-Presidents. Among the key leaders arrested, aside from Aung San Suu Kyi, are: President U Win Myint and Chief Ministers U Phyo Min Thein, Dr Zaw Myint Maung, Dr Aung Moe Nyo, Daw Nan Khin Htwe Myint, and U Nyi Pu. -

Commission Regulation (EC)

L 108/20 EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2009 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (3) Common Position 2009/351/CFSP of 27 April 2009 ( 2 ) amends Annexes II and III to Common Position 2006/318/CFSP of 27 April 2006. Annexes VI and VII Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 should, therefore, be Community, amended accordingly. Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 of (4) In order to ensure that the measures provided for in this 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive Regulation are effective, this Regulation should enter into measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regu- force immediately, lation (EC) No 817/2006 ( 1), and in particular Article 18(1)(b) thereof, HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Whereas: Article 1 1. Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby (1) Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists the replaced by the text of Annex I to this Regulation. persons, groups and entities covered by the freezing of funds and economic resources under that Regulation. 2. Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby replaced by the text of Annex II to this Regulation. (2) Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists enter- prises owned or controlled by the Government of Article 2 Burma/Myanmar or its members or persons associated with them, subject to restrictions on investment under This Regulation shall enter into force on the day of its publi- that Regulation. -

Burma's Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy

Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy Michael F. Martin Specialist in Asian Affairs Updated May 17, 2019 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44804 Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy Summary Despite a campaign pledge that they “would not arrest anyone as political prisoners,” Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) have failed to fulfil this promise since they took control of Burma’s Union Parliament and the government’s executive branch in April 2016. While presidential pardons have been granted for some political prisoners, people continue to be arrested, detained, tried, and imprisoned for alleged violations of Burmese laws. According to the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma), or AAPP(B), a Thailand-based, nonprofit human rights organization formed in 2000 by former Burmese political prisoners, there were 331 political prisoners in Burma as of the end of April 2019. During its three years in power, the NLD government has provided pardons for Burma’s political prisoners on six occasions. Soon after assuming office in April 2016, former President Htin Kyaw and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi took steps to secure the release of nearly 235 political prisoners. On May 23, 2017, former President Htin Kyaw granted pardons to 259 prisoners, including 89 political prisoners. On April 17, 2018, current President Win Myint pardoned 8,541 prisoners, including 36 political prisoners. In April and May 2019, he pardoned more than 23,000 prisoners, of which the AAPP(B) considered 20 as political prisoners. Aung San Suu Kyi and her government, as well as the Burmese military, however, also have demonstrated a willingness to use Burma’s laws to suppress the opinions of its political opponents and restrict press freedoms. -

CHAPTER 3 Myanmar Security Trend and Outlook:Tatmadaw in a New

CHAPTER 3 Myanmar Security Trend and Outlook: Tatmadaw in a New Political Environment Tin Maung Maung Than Introduction In March 2016, the Myanmar Armed Forces (MAF), or Myanmar Defence Services (MDS) which goes by the name “Tatmadaw (Royal Force),” supported the smooth transfer of power from President Thein Sein (whose Union Solidarity and Development Party lost the election) to President Htin Kyaw (nominated by the National League for Democracy that won the election).1 Despite speculations that the winning party and the Tatmadaw would lock horns as the former challenges the constitutionally-guaranteed political role of the military, the two protagonists seemed to have arrived at a modus vivendi that allowed for peaceful coexistence throughout the year. On the other hand, the last quarter of 2016 saw two seriously difficult security challenges that took the MDS by surprise both in terms of ferocity and suddenness. The consequences of the two violent attacks initiated by Muslim insurgents in the western Rakhine State, and an alliance of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in the northern Shan State, have gone beyond purely military challenges in view of their sheer complexity involving complicated issues of identity, ethnicity, and historical baggage as well as socio-economic and political grievances. Occurring at the border fo Bangladesh, the Rakhine conflagration, with religious and racial undertones, invited unwanted attention from Muslim countries while the fighting in the north bordering China raised concerns over potential Chinese reaction to serve its national interest. As such, Tatmadaw’s massive response to these challenges came under great scrutiny from the international community in general and human rights advocacy groups in particular. -

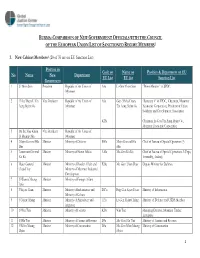

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry