Burma: the Quiet Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar Business Guide for Brazilian Businesses

2019 Myanmar Business Guide for Brazilian Businesses An Introduction of Business Opportunities and Challenges in Myanmar Prepared by Myanmar Research | Consulting | Capital Markets Contents Introduction 8 Basic Information 9 1. General Characteristics 10 1.1. Geography 10 1.2. Population, Urban Centers and Indicators 17 1.3. Key Socioeconomic Indicators 21 1.4. Historical, Political and Administrative Organization 23 1.5. Participation in International Organizations and Agreements 37 2. Economy, Currency and Finances 38 2.1. Economy 38 2.1.1. Overview 38 2.1.2. Key Economic Developments and Highlights 39 2.1.3. Key Economic Indicators 44 2.1.4. Exchange Rate 45 2.1.5. Key Legislation Developments and Reforms 49 2.2. Key Economic Sectors 51 2.2.1. Manufacturing 51 2.2.2. Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry 54 2.2.3. Construction and Infrastructure 59 2.2.4. Energy and Mining 65 2.2.5. Tourism 73 2.2.6. Services 76 2.2.7. Telecom 77 2.2.8. Consumer Goods 77 2.3. Currency and Finances 79 2.3.1. Exchange Rate Regime 79 2.3.2. Balance of Payments and International Reserves 80 2.3.3. Banking System 81 2.3.4. Major Reforms of the Financial and Banking System 82 Page | 2 3. Overview of Myanmar’s Foreign Trade 84 3.1. Recent Developments and General Considerations 84 3.2. Trade with Major Countries 85 3.3. Annual Comparison of Myanmar Import of Principal Commodities 86 3.4. Myanmar’s Trade Balance 88 3.5. Origin and Destination of Trade 89 3.6. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

Acts Adopted Under Title V of the Treaty on European Union)

L 108/88EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2005 (Acts adopted under Title V of the Treaty on European Union) COUNCIL COMMON POSITION 2005/340/CFSP of 25 April 2005 extending restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Common Position 2004/423/CFSP THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, (8) In the event of a substantial improvement in the overall political situation in Burma/Myanmar, the suspension of Having regard to the Treaty on European Union, and in these restrictive measures and a gradual resumption of particular Article 15 thereof, cooperation with Burma/Myanmar will be considered, after the Council has assessed developments. Whereas: (9) Action by the Community is needed in order to (1) On 26 April 2004, the Council adopted Common implement some of these measures, Position 2004/423/CFSP renewing restrictive measures 1 against Burma/Myanmar ( ). HAS ADOPTED THIS COMMON POSITION: (2) On 25 October 2004, the Council adopted Common Position 2004/730/CFSP on additional restrictive Article 1 measures against Burma/Myanmar and amending Annexes I and II to Common Position 2004/423/CFSP shall be Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (2). replaced by Annexes I and II to this Common Position. (3) On 21 February 2005, the Council adopted Common Position 2005/149/CFSP amending Annex II to Article 2 Common Position 2004/423/CFSP (3). Common Position 2004/423/CFSP is hereby renewed for a period of 12 months. (4) The Council would recall its position on the political situation in Burma/Myanmar and considers that recent developments do not justify suspension of the restrictive Article 3 measures. -

The Generals Loosen Their Grip

The Generals Loosen Their Grip Mary Callahan Journal of Democracy, Volume 23, Number 4, October 2012, pp. 120-131 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/jod.2012.0072 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/jod/summary/v023/23.4.callahan.html Access provided by Stanford University (9 Jul 2013 18:03 GMT) The Opening in Burma the generals loosen their grip Mary Callahan Mary Callahan is associate professor in the Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies at the University of Washington. She is the author of Making Enemies: War and State Building in Burma (2003) and Political Authority in Burma’s Ethnic Minority States: Devolution, Occupation and Coexistence (2007). Burma1 is in the midst of a political transition whose contours suggest that the country’s political future is “up for grabs” to a greater degree than has been so for at least the last half-century. Direct rule by the mili- tary as an institution is over, at least for now. Although there has been no major shift in the characteristics of those who hold top government posts (they remain male, ethnically Burman, retired or active-duty mili- tary officers), there exists a new political fluidity that has changed how they rule. Quite unexpectedly, the last eighteen months have seen the retrenchment of the military’s prerogatives under decades-old draconian “national-security” mandates as well as the emergence of a realm of open political life that is no longer considered ipso facto nation-threat- ening. Leaders of the Tatmadaw (Defense Services) have defined and con- trolled the process. -

Myanmar Military Should End Its Use of Violence and Respect Democracy

2021-02-01 MYANMAR MILITARY SHOULD END ITS USE OF VIOLENCE AND RESPECT DEMOCRACY The undersigned groups today denounced an apparent coup in Myanmar, and associated violence, which has suspended civilian government and effectively returned full power to the military. On 1 February, the military arbitrarily detained State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and other leaders of the National League for Democracy. A year-long state of emergency was declared, installing Vice-President and former lieutenant-general Myint Swe as the acting President. Myint Swe immediately handed over power to commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing (Section 418 of Myanmar’s 2008 Constitution enables transfer of legislative, executive, and judicial powers to the Commander in Chief). Internet connections and phone lines throughout the country were disrupted, pro-democracy activists have been arbitrarily arrested, with incoming reports of increased detentions. Soldiers in armoured cars have been visibly roaming Naypyitaw and Yangon, raising fears of lethal violence. “The military should immediately and unconditionally release all detained and return to Parliament to reach a peaceful resolution with all relevant parties,” said the groups. The military and its aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) had disputed the results of the November elections, which saw the majority of the seats won by the NLD. The arrests of the leaders came just before the Parliament was due to convene for the first time in order to pick the President and Vice-Presidents. Among the key leaders arrested, aside from Aung San Suu Kyi, are: President U Win Myint and Chief Ministers U Phyo Min Thein, Dr Zaw Myint Maung, Dr Aung Moe Nyo, Daw Nan Khin Htwe Myint, and U Nyi Pu. -

Children in Burma (Myanmar)

Children as Beneficiaries and Participants in Development Programs: A Case Study in Burma (Myanmar) Karl Goodwin-Doming Faculty of Arts Department of Social Inquiry & Community Studies Victoria University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2007 Abstract This study seeks to understand the dynamics and processes of community development programs for children in Burma (Myanmar). It examines the ethical dimensions of children's participation, critiques the extent of participation of young people in community development activity, explores the barriers and avenues for increased participation and presents recommendations based on lived experience which can be used to formulate policies that will enable/encourage greater participation. The development industry reaches to almost all areas of the globe and is not confined by national boundaries, ethnicity, age, gender or other social stratification. One of the most topical issues in contemporary development regards the rights of the child. It is an area of increasing interest to United Nations agencies and to human rights groups such as Amnesty International and the International Labour Organisation. In addition, a number of international programs have been created to focus upon improving the global situation of children, such as the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and Mandela and Machel's "Global Movement for Children." Such interest in the situation of children, however, rarely includes discussion of the ethical issues involved in the construction of children as appropriate subjects of development. Even rarer is examination or discussion of the culturally and historically contingent nature of assumptions about children and childhood that are built into many programs that focus upon children. -

CHAPTER 3 Myanmar Security Trend and Outlook:Tatmadaw in a New

CHAPTER 3 Myanmar Security Trend and Outlook: Tatmadaw in a New Political Environment Tin Maung Maung Than Introduction In March 2016, the Myanmar Armed Forces (MAF), or Myanmar Defence Services (MDS) which goes by the name “Tatmadaw (Royal Force),” supported the smooth transfer of power from President Thein Sein (whose Union Solidarity and Development Party lost the election) to President Htin Kyaw (nominated by the National League for Democracy that won the election).1 Despite speculations that the winning party and the Tatmadaw would lock horns as the former challenges the constitutionally-guaranteed political role of the military, the two protagonists seemed to have arrived at a modus vivendi that allowed for peaceful coexistence throughout the year. On the other hand, the last quarter of 2016 saw two seriously difficult security challenges that took the MDS by surprise both in terms of ferocity and suddenness. The consequences of the two violent attacks initiated by Muslim insurgents in the western Rakhine State, and an alliance of ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in the northern Shan State, have gone beyond purely military challenges in view of their sheer complexity involving complicated issues of identity, ethnicity, and historical baggage as well as socio-economic and political grievances. Occurring at the border fo Bangladesh, the Rakhine conflagration, with religious and racial undertones, invited unwanted attention from Muslim countries while the fighting in the north bordering China raised concerns over potential Chinese reaction to serve its national interest. As such, Tatmadaw’s massive response to these challenges came under great scrutiny from the international community in general and human rights advocacy groups in particular. -

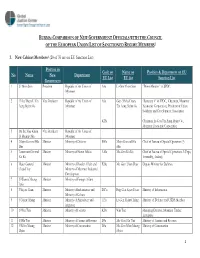

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

Burma's 2015 Parliamentary Elections: Issues for Congress

Burma’s 2015 Parliamentary Elections: Issues for Congress Michael F. Martin Specialist in Asian Affairs March 28, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44436 Burma’s 2015 Parliamentary Elections: Issues for Congress Summary The landslide victory of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) in Burma’s November 2015 parliamentary elections may prove to be a major step in the nation’s potential transition to a more democratic government. Having won nearly 80% of the contested seats in the election, the NLD has a majority in both chambers of the Union Parliament, which gave it the ability to select the President-elect, as well as control of most of the nation’s Regional and State Parliaments. Burma’s 2008 constitution, however, grants the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw, widespread powers in the governance of the nation, and nearly complete autonomy from civilian control. One quarter of the seats in each chamber of the Union Parliament are reserved for military officers appointed by the Tatmadaw’s Commander-in-Chief, giving them the ability to block any constitutional amendments. Military officers constitute a majority of the National Defence and Security Council, an 11-member body with some oversight authority over the President. The constitution also grants the Tatmadaw “the right to independently administer and adjudicate all affairs of the armed services,” and designates the Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services as “the ‘Supreme Commander’ of all armed forces,” which could have serious implications for efforts to end the nation’s six-decade-long, low-grade civil war. -

YCDC Planning to Build 50 Mln Euro Worth Waste to Energy Plant in Htainpin Dump Site

NEED TO ENCOURAGE LITERARY ARENA AND LITERATI TO CREATE BETTER WORKS PAGE-8 (OPINION) Vol. VIII, No. 56, 5th Waxing of Nayon 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Monday, 14 June 2021 Press Statement from Ministry of Foreign Affairs MYANMAR categorically rejects the statement of the who support unlawful associations and terrorist The United Nations High Commissioner for Hu- United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights groups such as the so-called National Unity Govern- man Rights has been mandated to promote and pro- Ms. Michelle Bachelet pertaining to the situation in ment and the People’s Defence Forces do not want tect all human rights for all in an impartial manner Myanmar issued on 11 June 2021. It is learnt that the teachers and civil servants to perform their assigned in line with the United Nations General Assembly’s facts mentioned in the statement are lack of accuracy duties and has committed arson and bomb attacks Resolution A/RES/48/141 dated 7 January 1994. Thus, and impartiality. against schools which caused killings of innocent in accordance with her mandate, she needs to be fair The report mentioned the attacks on schools and civilians including administrative and educational and impartial while performing her duties, particularly religious bulidings and the uses of public housing by personnel. addressing the situation of the country. the Tatmadaw which leads to misunderstanding to In carrying out public safety duties, the Tatmadaw Myanmar wishes her to conduct her works in an the public. However, the report neither mentioned has been paying special attention to ensure the safety impartial, objective and constructive manner while nor condemned the acts of sabotage and terrorism of innocent people, the law enforcement and the rule of upholding the provisions of the Charter of the United committed by the unlawful associations and terrorist law within the existing legal framework. -

Burma's Union Parliament Selects New President

CRS INSIGHT Burma's Union Parliament Selects New President March 18, 2016 (IN10464) | Related Policy Issue Southeast Asia, Australasia, and the Pacific Islands Related Author Michael F. Martin | Michael F. Martin, Specialist in Asian Affairs ([email protected], 7-2199) On March 15, 2016, Burma's Union Parliament selected Htin Kyaw, childhood friend and close advisor to Aung San Suu Kyi, to serve as the nation's first President since 1962 who has not served in the military. His selection as President-Elect completes another step in the nation's five-month-long transition from a largely military-controlled government to one led by the National League for Democracy (NLD). In addition, it also marks at least a temporary end to Aung San Suu Kyi's efforts to become Burma's President and may reveal signs of growing tensions between the NLD and the Burmese military. Htin Kyaw received the support of 360 of the 652 Members of Parliament (MPs), defeating retired Lt. General Myint Swe (who received 213 votes, of which 166 were from military MPs) and Henry Na Thio (who received 79 votes). The 69-year-old President-Elect is expected to be sworn into office on March 30, 2016. Myint Swe and Henry Van Thio will serve as 1st and 2nd Vice President, respectively. On November 8, 2015, Aung San Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy (NLD) won a landslide victory in nationwide parliamentary elections (see CRS Insight IN10397, Burma's Parliamentary Elections, by Michael F. Martin) that gave the party a majority of the seats in both chambers of Burma's Union Parliament. -

VP U Myint Swe Holds Meeting on Completion of Renovation Works of Bagan, Nyaung-U Temples

VACCINATION: VICTORY AGAINST PANDEMIC PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Union Minister for Defence receives Land administration central committee UNHCR Representative holds 32nd coordination meeting PAGE-3 PAGE-4 Vol. VII, No. 286, Fullmoon of Pyatho 1382 ME www.gnlm.com.mm, www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Wednesday, 27 January 2021 VP U Myint Swe holds meeting on completion of renovation works of Bagan, Nyaung-U temples ICE-President U Myint Swe chaired the 5th coor- Vdination meeting yester- day on the completion of renova- tion works at ancient temples, pagodas and religious buildings in the earthquake-stricken Ba- gan and Nyaung-U areas. In his opening speech, the Vice-President explained the works of the steering commit- tee, the formation of two work committees and five sub-com- mittees, as well as consultant and expert teams which are working with the international cooperation committees, reno- vating the sacred sites hit by a major quake on 24 August 2016. He also said that a total of 388 damaged temples and stupas have been renovated in the past four years and that the exten- sive renovation to Thatbinnyu temple will be carried out under the nine-year project with assis- Vice-President U Myint Swe presides over the fifth meeting on the completion of renovation works of Bagan, Nyaung-U Temples, on 26 January tance from the People’s Republic 2021. PHOTO : MNA of China. Some restoration works advised on the proper manage- against future disasters, and to tions concerned for their partic- steering committee, reported on were also conducted at the other ment of funds donated by local strengthen security measures in ipation in the renovation efforts.