Children in Burma (Myanmar)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myanmar Business Guide for Brazilian Businesses

2019 Myanmar Business Guide for Brazilian Businesses An Introduction of Business Opportunities and Challenges in Myanmar Prepared by Myanmar Research | Consulting | Capital Markets Contents Introduction 8 Basic Information 9 1. General Characteristics 10 1.1. Geography 10 1.2. Population, Urban Centers and Indicators 17 1.3. Key Socioeconomic Indicators 21 1.4. Historical, Political and Administrative Organization 23 1.5. Participation in International Organizations and Agreements 37 2. Economy, Currency and Finances 38 2.1. Economy 38 2.1.1. Overview 38 2.1.2. Key Economic Developments and Highlights 39 2.1.3. Key Economic Indicators 44 2.1.4. Exchange Rate 45 2.1.5. Key Legislation Developments and Reforms 49 2.2. Key Economic Sectors 51 2.2.1. Manufacturing 51 2.2.2. Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry 54 2.2.3. Construction and Infrastructure 59 2.2.4. Energy and Mining 65 2.2.5. Tourism 73 2.2.6. Services 76 2.2.7. Telecom 77 2.2.8. Consumer Goods 77 2.3. Currency and Finances 79 2.3.1. Exchange Rate Regime 79 2.3.2. Balance of Payments and International Reserves 80 2.3.3. Banking System 81 2.3.4. Major Reforms of the Financial and Banking System 82 Page | 2 3. Overview of Myanmar’s Foreign Trade 84 3.1. Recent Developments and General Considerations 84 3.2. Trade with Major Countries 85 3.3. Annual Comparison of Myanmar Import of Principal Commodities 86 3.4. Myanmar’s Trade Balance 88 3.5. Origin and Destination of Trade 89 3.6. -

Burma Coup Watch

This publication is produced in cooperation with Burma Human Rights Network (BHRN), Burmese Rohingya Organisation UK (BROUK), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), Progressive Voice (PV), US Campaign for Burma (USCB), and Women Peace Network (WPN). BN 2021/2031: 1 Mar 2021 BURMA COUP WATCH: URGENT ACTION REQUIRED TO PREVENT DESTABILIZING VIOLENCE A month after its 1 February 2021 coup, the military junta’s escalation of disproportionate violence and terror tactics, backed by deployment of notorious military units to repress peaceful demonstrations, underlines the urgent need for substantive international action to prevent massive, destabilizing violence. The junta’s refusal to receive UN diplomatic and CONTENTS human rights missions indicates a refusal to consider a peaceful resolution to the crisis and 2 Movement calls for action confrontation sparked by the coup. 2 Coup timeline 3 Illegal even under the 2008 In order to avert worse violence and create the Constitution space for dialogue and negotiations, the 4 Information warfare movement in Burma and their allies urge that: 5 Min Aung Hlaing’s promises o International Financial Institutions (IFIs) 6 Nationwide opposition immediately freeze existing loans, recall prior 6 CDM loans and reassess the post-coup situation; 7 CRPH o Foreign states and bodies enact targeted 7 Junta’s violent crackdown sanctions on the military (Tatmadaw), 8 Brutal LIDs deployed Tatmadaw-affiliated companies and partners, 9 Ongoing armed conflict including a global arms embargo; and 10 New laws, amendments threaten human rights o The UN Security Council immediately send a 11 International condemnation delegation to prevent further violence and 12 Economy destabilized ensure the situation is peacefully resolved. -

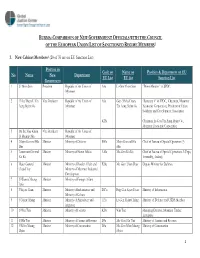

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

Burma: the Quiet Violence

Burma: The Quiet Violence Political Paintings by Myint Swe Text by Shireen Naziree 98 BURMA: THE QUIET VIOLENCE Burma: The Quiet Violence Political Paintings by Myint Swe Text by Shireen Naziree Published 2009 by Thavibu Gallery Co., Ltd Silom Galleria, Suite 308 919/1 Silom Road, Bangkok 10500, Thailand Tel. 66 (0)2 266 5454, Fax. 66 (0)2 266 5455 Email. [email protected], www.thavibu.com Language Editor, James Pruess Layout by Wanee Tipchindachaikul, Copydesk, Thailand Copyright Thavibu Gallery All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. CONTENTS Foreword 6 Burma: The Quiet Violence - Introduction 7 The Quiet Violence 9 My Outlook and Attitudes Towards Art and Life by Myint Swe 18 PLATES: Paintings of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi 19 PLATES: Other Paintings 41 Myint Swe’s Biography 98 FOREWORD Jørn Middelborg Thavibu Gallery Thavibu Gallery is pleased to present the collection of political paintings, “Burma: The Quiet Violence,” by Myint Swe. The collection features 38 paintings that reflect the artist’s concerns about the detention of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the discouraging socio-political environment in Burma. The paintings were executed in Rangoon between 1997 and 2005 and secretly transported to Bangkok where they have been stored for some years. However, due to the worsening situation in Burma, it has become necessary to remind a wider audience of the atrocities of the military junta. And while the paintings of artists such as Myint Swe will not change the political climate of Burma, we applaud his courage as he and other artists risk their lives and the future of their families by commenting on their country’s grave and tragic state. -

Burma's 2015 Parliamentary Elections: Issues for Congress

Burma’s 2015 Parliamentary Elections: Issues for Congress Michael F. Martin Specialist in Asian Affairs March 28, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R44436 Burma’s 2015 Parliamentary Elections: Issues for Congress Summary The landslide victory of Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) in Burma’s November 2015 parliamentary elections may prove to be a major step in the nation’s potential transition to a more democratic government. Having won nearly 80% of the contested seats in the election, the NLD has a majority in both chambers of the Union Parliament, which gave it the ability to select the President-elect, as well as control of most of the nation’s Regional and State Parliaments. Burma’s 2008 constitution, however, grants the Burmese military, or Tatmadaw, widespread powers in the governance of the nation, and nearly complete autonomy from civilian control. One quarter of the seats in each chamber of the Union Parliament are reserved for military officers appointed by the Tatmadaw’s Commander-in-Chief, giving them the ability to block any constitutional amendments. Military officers constitute a majority of the National Defence and Security Council, an 11-member body with some oversight authority over the President. The constitution also grants the Tatmadaw “the right to independently administer and adjudicate all affairs of the armed services,” and designates the Commander-in-Chief of Defence Services as “the ‘Supreme Commander’ of all armed forces,” which could have serious implications for efforts to end the nation’s six-decade-long, low-grade civil war. -

YCDC Planning to Build 50 Mln Euro Worth Waste to Energy Plant in Htainpin Dump Site

NEED TO ENCOURAGE LITERARY ARENA AND LITERATI TO CREATE BETTER WORKS PAGE-8 (OPINION) Vol. VIII, No. 56, 5th Waxing of Nayon 1383 ME www.gnlm.com.mm Monday, 14 June 2021 Press Statement from Ministry of Foreign Affairs MYANMAR categorically rejects the statement of the who support unlawful associations and terrorist The United Nations High Commissioner for Hu- United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights groups such as the so-called National Unity Govern- man Rights has been mandated to promote and pro- Ms. Michelle Bachelet pertaining to the situation in ment and the People’s Defence Forces do not want tect all human rights for all in an impartial manner Myanmar issued on 11 June 2021. It is learnt that the teachers and civil servants to perform their assigned in line with the United Nations General Assembly’s facts mentioned in the statement are lack of accuracy duties and has committed arson and bomb attacks Resolution A/RES/48/141 dated 7 January 1994. Thus, and impartiality. against schools which caused killings of innocent in accordance with her mandate, she needs to be fair The report mentioned the attacks on schools and civilians including administrative and educational and impartial while performing her duties, particularly religious bulidings and the uses of public housing by personnel. addressing the situation of the country. the Tatmadaw which leads to misunderstanding to In carrying out public safety duties, the Tatmadaw Myanmar wishes her to conduct her works in an the public. However, the report neither mentioned has been paying special attention to ensure the safety impartial, objective and constructive manner while nor condemned the acts of sabotage and terrorism of innocent people, the law enforcement and the rule of upholding the provisions of the Charter of the United committed by the unlawful associations and terrorist law within the existing legal framework. -

VP U Myint Swe Holds Meeting on Completion of Renovation Works of Bagan, Nyaung-U Temples

VACCINATION: VICTORY AGAINST PANDEMIC PAGE-8 (OPINION) NATIONAL NATIONAL Union Minister for Defence receives Land administration central committee UNHCR Representative holds 32nd coordination meeting PAGE-3 PAGE-4 Vol. VII, No. 286, Fullmoon of Pyatho 1382 ME www.gnlm.com.mm, www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Wednesday, 27 January 2021 VP U Myint Swe holds meeting on completion of renovation works of Bagan, Nyaung-U temples ICE-President U Myint Swe chaired the 5th coor- Vdination meeting yester- day on the completion of renova- tion works at ancient temples, pagodas and religious buildings in the earthquake-stricken Ba- gan and Nyaung-U areas. In his opening speech, the Vice-President explained the works of the steering commit- tee, the formation of two work committees and five sub-com- mittees, as well as consultant and expert teams which are working with the international cooperation committees, reno- vating the sacred sites hit by a major quake on 24 August 2016. He also said that a total of 388 damaged temples and stupas have been renovated in the past four years and that the exten- sive renovation to Thatbinnyu temple will be carried out under the nine-year project with assis- Vice-President U Myint Swe presides over the fifth meeting on the completion of renovation works of Bagan, Nyaung-U Temples, on 26 January tance from the People’s Republic 2021. PHOTO : MNA of China. Some restoration works advised on the proper manage- against future disasters, and to tions concerned for their partic- steering committee, reported on were also conducted at the other ment of funds donated by local strengthen security measures in ipation in the renovation efforts. -

Recent Arrests List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 8 of the Export and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Import Law and S: 25 Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and of the Natural Disaster Lin of Special Branch regions were also detained. Management law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 25 of the Natural President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and Naing law regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and parliament regions were also detained. -

President U Win Myint Cultivates Mahogany Plant to Launch 2020

FOCUS ON MENTAL HEALTH IN NEW NORMAL PAGE-8 (OPINION) PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT Pyithu Hluttaw raises questions to Nay Pyi Taw Council, Amyotha Hluttaw raises queries to ministries, approves Central Provident Fund Bill, three ministries, hears bill, report Underwater Management Bill PAGE-2 PAGE-2 Vol. VII, No. 113, 4th Waning of Second Waso 1382 ME www.globalnewlightofmyanmar.com Friday, 7 August 2020 President U Win Myint cultivates State Counsellor remarks Mahogany plant to launch 2020 “nation is strong and sturdy only Greening Campaign when the smallest areas are strong” President U Win Myint is cultivating a Mahogany plant at monsoon plantation ceremony in State Counsellor holds meeting with local officials in Cocogyun Township on 6 August. Nay Pyi Taw on 6 August. PHOTO: MNA PHOTO: MNA RESIDENT U Win Myint took part in the monsoon plantation ceremony for TATE Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, in her capacity as Chairperson conducting 2020 greening campaign, organized in Phoe Zaung Taung Reserved of the Central Committee for Development of Border Areas and National PForest beside Nay Pyi Taw-Tatkon No.1 road in Ottarathiri Township in Nay SRaces, visited Cocogyun Township yesterday. She held talks on development Pyi Taw yesterday morning. programmes of the township with departmental officials and viewed the high school Vice Presidents U Myint Swe and U Henry Van Thio, the Union Ministers, the and the people’s hospital. Deputy Minister for Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation, permanent secretaries and officials. SEE PAGE-3 -

Community Directory People from Burma/Myanmar

Community Directory People from Burma/Myanmar Project Initiative Burmese Advisory Committee Creative editor & compilation Aung Thu Consultancy Mark Caruana Administrative assistance Elizabeth Philpsz Cover design Ye Win This Community Directory is an updated publication of the Baulkham Hills Holroyd Parramatta Migrant Resource Center Inc. 15 Hunter St, Parramatta NSW 2150 Tel: (02) 9687 9901 Fax: (02) 9687 9990 E-mail [email protected] Disclaimer Every effort has been made to ensure that the information provided is correct. However, BHHP MRC will not bear any responsibility for information that has changed after the publication of this document. Printed by: Click Printing Shop 2, Ground Floor, 34 Campbell St, Blacktown NSW 2148 Tel: (02) 9831 1993 Fax: (02) 9831 3174 Copyright: BHHP MRC All material is copyright and cannot be reproduced in full or part without the written permission of the publisher. ISSN 1832-7974 2006 Reprint Table of Contents Foreword a Acknowledgement b About Australia Migration from Burma 1 Census 1-3 Information for new arrivals 4-11 Media 12-13 Religion & Associations 14-19 Periodical Publications & Health 19 Projects for Students 20 Businesses Medical Doctors, Dentists, Optometrists 21-24 Lawyers, Interpreters 25 Businesses Export & Import 26 On Line Businesses, Dine in & Take away 27 Finance 28 Design & Construction, Electricians 29 Mixed Businesses, Finance 30 Activities Social and Welfare Groups 31 Community Organizations 32-34 Sports & Entertainment 34 Burmese in New Zealand Religion 36 Media 36 Education & Training 37 Social & Welfare Groups 37 About Burma Map, Geography and History 38-40 Facts about Burma 41 Ethnic Map, Heritage, Burmese culture 42-50 National Anthem & State Seals 51-54 Burmese Embassies Abroad 54-55 Australian Embassies Abroad 56-57 How to Find Related Websites for Burma 58-60 FOREWORD For a long time, migrants from Burma in Australia have felt the need for a Community Directory. -

ASG Analysis: Myanmar Military Seizes Power February 2, 2021

ASG Analysis: Myanmar Military Seizes Power February 2, 2021 Key Takeaways • The Tatmadaw (Myanmar military) arrested the leaders of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in coordinated early morning raids February 1, bringing to conclusion a month of escalating tensions and overthrowing Myanmar’s government 10 years after the country returned to democracy. • The coup thus far has been bloodless, but there have been reports of military supporters harassing journalists and NLD sympathizers, and many analysts fear violence could erupt in major cities such as Yangon and Mandalay, where resentment of the military runs deep. The Tatmadaw’s justification for the coup was alleged voter fraud in the 2020 general election. • While the Tatmadaw has announced it intends to hold “free and fair elections” and hand over power to the winner, it will likely attempt to reform electoral rules further in order to have more control over the outcome. • ASG expects the Biden administration to place sanctions on Myanmar’s military government, likely through the Global Magnitsky Act rather than any new structure. Military holding companies such as Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC) and Myanma Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL) are likely targets. Those two entities are so significant within the country’s economy that renewed sanctions on them would make U.S. investment in the country extremely difficult. Democratically elected government overthrown in first coup since 1988 The Tatmadaw (Myanmar military) arrested the leaders of the National League for Democracy (NLD) in coordinated early morning raids February 1, bringing to conclusion a month of escalating tensions and overthrowing Myanmar’s government 10 years after the country returned to democracy. -

A History of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964)

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2008 A history of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964) Kyaw Zaw Win University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Win, Kyaw Z, A history of the Burma Socialist Party (1930-1964), PhD thesis, School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2008.