Burma's Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remaking Rakhine State

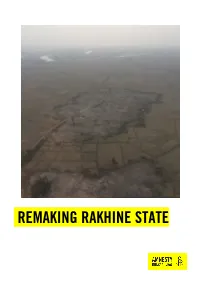

REMAKING RAKHINE STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Aerial photograph showing the clearance of a burnt village in northern Rakhine State (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Private https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 16/8018/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org INTRODUCTION Six months after the start of a brutal military campaign which forced hundreds of thousands of Rohingya women, men and children from their homes and left hundreds of Rohingya villages burned the ground, Myanmar’s authorities are remaking northern Rakhine State in their absence.1 Since October 2017, but in particular since the start of 2018, Myanmar’s authorities have embarked on a major operation to clear burned villages and to build new homes, security force bases and infrastructure in the region. -

Senate TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2018

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2018 No. 155 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Thursday, September 20, 2018, at 9:30 a.m. Senate TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2018 The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, until they leaked it to the press on the called to order by the Honorable CINDY PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, eve of the scheduled committee vote. Washington, DC, September 18, 2018. HYDE-SMITH, a Senator from the State But as my colleague, the senior Sen- of Mississippi. To the Senate. ator from Texas, said yesterday, the f Under the provisions of rule I, para- graph 3, of the Standing Rules of the blatant malpractice demonstrated by PRAYER Senate, I hereby appoint the Honorable our colleagues across the aisle will not The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- CINDY HYDE-SMITH, a Senator from the stop the Senate from moving forward fered the following prayer: State of Mississippi, to perform the du- in a responsible manner. Let us pray. ties of the Chair. As I said yesterday, I have full con- Eternal God, whose mercy is great ORRIN G. HATCH, unto the Heavens, help us to do what is President pro tempore. fidence in Chairman GRASSLEY to lead right. May we not forget that You are Mrs. HYDE-SMITH thereupon as- the committee through the sensitive the judge of the Earth and that we are sumed the Chair as Acting President and highly irregular situation in which accountable to You. -

The Sentinel Period Ending 27 Oct 2018

The Sentinel Human Rights Action :: Humanitarian Response :: Health :: Education :: Heritage Stewardship :: Sustainable Development __________________________________________________ Period ending 27 October 2018 This weekly digest is intended to aggregate and distill key content from a broad spectrum of practice domains and organization types including key agencies/IGOs, NGOs, governments, academic and research institutions, consortiums and collaborations, foundations, and commercial organizations. We also monitor a spectrum of peer- reviewed journals and general media channels. The Sentinel’s geographic scope is global/regional but selected country-level content is included. We recognize that this spectrum/scope yields an indicative and not an exhaustive product. The Sentinel is a service of the Center for Governance, Evidence, Ethics, Policy & Practice, a program of the GE2P2 Global Foundation, which is solely responsible for its content. Comments and suggestions should be directed to: David R. Curry Editor, The Sentinel President. GE2P2 Global Foundation [email protected] The Sentinel is also available as a pdf document linked from this page: http://ge2p2-center.net/ Support this knowledge-sharing service: Your financial support helps us cover our costs and address a current shortfall in our annual operating budget. Click here to donate and thank you in advance for your contribution. _____________________________________________ Contents [click on link below to move to associated content] :: Week in Review :: Key Agency/IGO/Governments Watch - Selected Updates from 30+ entities :: INGO/Consortia/Joint Initiatives Watch - Media Releases, Major Initiatives, Research :: Foundation/Major Donor Watch -Selected Updates :: Journal Watch - Key articles and abstracts from 100+ peer-reviewed journals :: Week in Review A highly selective capture of strategic developments, research, commentary, analysis and announcements spanning Human Rights Action, Humanitarian Response, Health, Education, Holistic Development, Heritage Stewardship, Sustainable Resilience. -

Qatar, Italy Sign Pacts on a Wide Range of Areas

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Infantino, Thawadi confi dent Qatar among leading of a great countries in business continuity, resilience World Cup published in QATAR since 1978 WEDNESDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 11009 November 21, 2018 Rabia I 13, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals In brief MbS may have QATAR | Reaction Qatar condemns Kabul known of celebration hall blast Qatar expressed its strong condemnation of the explosion that took place in a celebration hall Khashoggi in Kabul and left several people killed and injured. In a statement issued yesterday, the Ministry of Foreign Aff airs reiterated the Qatar’s firm stance in rejecting violence murder: Trump and terrorism regardless of the motives and causes. The statement expressed Qatar’s condolences to the families of victims as well z US president vows unstinting as the government and people of Afghanistan, wishing the injured a support to Saudi Arabia speedy recovery. zKhashoggi killing a terrible crime, UNITED NATIONS | Diplomacy His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani with Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte during the off icial says White House but prefers Saudi UN chief hails reception ceremony accorded to him at Villa Doria Pamphili in Rome yesterday. Page 3 al-Nasser’s leadership UN Secretary-General Antonio position over CIA fi ndings Guterres underlined that the UN Alliance of Civilizations has been Agencies tal of offers since Trump took office is ably led by HE Nassir Abdulaziz Washington less than $15bn, and the value of ac- al-Nasser over the past six years, tual signed contracts is significantly during a period of unprecedented lower than that, a Guardian report challenges to peace and security. -

B U R M a B U L L E T

B U R M A B U L L E T I N ∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞A month-in-review of events in Burma∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞ A L T E R N A T I V E A S E A N N E T W O R K O N B U R M A campaigns, advocacy & capacity-building for human rights & democracy Issue 20 August 2008 • Fearing a wave of demonstrations commemorating th IN THIS ISSUE the 20 anniversary of the nationwide uprising, the SPDC embarks on a massive crackdown on political KEY STORY activists. The regime arrests 71 activists, including 1 August crackdown eight NLD members, two elected MPs, and three 2 Activists arrested Buddhist monks. 2 Prison sentences • Despite the regime’s crackdown, students, workers, 3 Monks targeted and ordinary citizens across Burma carry out INSIDE BURMA peaceful demonstrations, activities, and acts of 3 8-8-8 Demonstrations defiance against the SPDC to commemorate 8-8-88. 4 Daw Aung San Suu Kyi 4 Cyclone Nargis aid • Daw Aung San Suu Kyi is allowed to meet with her 5 Cyclone camps close lawyer for the first time in five years. She also 5 SPDC aid windfall receives a visit from her doctor. Daw Suu is rumored 5 Floods to have started a hunger strike. 5 More trucks from China • UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Burma HUMAN RIGHTS 5 Ojea Quintana goes to Burma Tomás Ojea Quintana makes his first visit to the 6 Rape of ethnic women country. The SPDC controls his meeting agenda and restricts his freedom of movement. -

Yangon Region Gov't, HK-Taiwan Consortium Ink Industrial Zone Deal

Business Yangon Region Gov’t, HK-Taiwan Consortium Ink Industrial Zone Deal Yangon Region Minister for Planning and Finance U Myint Thaung delivers the opening speech at a press conference at the Yangon Investment Forum 2019. / The Global New Light of Myanmar By THE IRRAWADDY 29 April 2019 YANGON—The Yangon regional government will sign a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with a consortium of Hong Kong and Taiwan companies next month to develop an international-standard industrial zone in Htantabin Township in the west of the commercial capital. Worth an estimated US$500 million (761.2 billion kyats) the Htantabin Industrial Zone will be implemented on more than 1,000 acres and is expected to create more than 150,000 job opportunities, said Naw Pan Thinzar Myo, Yangon Region Karen ethnic affairs minister, at a press conference on Friday. The regional government and the Hong Kong-Taiwan consortium, Golden Myanmar Investment Co., are scheduled to sign the MoU at the 2nd Yangon Investment Fair on May 10, which will showcase about 80 projects across Yangon Region in an effort to drum up local and foreign investment. It is expected to take about nine years to fully implement the Htantabin Industrial Zone. The MoU is the first to be implemented among 11 industrial zones planned by the Yangon regional government in undeveloped areas on the outskirts of Yangon. A map of the Htantabin Industrial Zone / Invest Myanmar Summit website At the country’s first Investment Fair in late January, the Yangon government showcased planned international-standard industrial zones in 11 townships: Kungyangon, Kawhmu, Twantay, Thingyan, Kyauktan, Khayan, Thongwa, Taikkyi, Hmawbi, Hlegu and Htantabin. -

Please Copy and Paste the Following Text Into Your E-Mail

Please copy and paste the following text into your e-mail To: UN Human Rights Council Member States’ foreign ministers and their country missions in Geneva On 1 February, the Myanmar military seized power in a military coup d'etat and arbitrarily detained President Win Myint, State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and other civilian leaders. A year-long state of emergency was declared, installing Vice-President and former lieutenant- general Myint Swe as the acting President, who immediately handed over power to commander- in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing. The coup has been met with nationwide peaceful demonstrations by the people of Myanmar demanding that the Military respects the outcomes of the November 2020 elections, restores the elected civilian government and releases all those who are arbitrarily detained, and that the Military be held accountable for its atrocities. The junta has responded to these protests with systematic and violent crackdowns. The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar has described the junta’s crackdown on peaceful protestors as crimes against humanity. Since the coup, over 755 people, including at least 43 children, women and medical workers have been killed so far in the junta’s violence. Also, over 4,496 people, including human rights defenders and journalists documenting the military’s atrocities, civil society and political activists, and civilian political leaders have been arbitrarily arrested and detained and raided their offices and homes. Whereabouts of many who have been arrested remain unknown while several others have reported torture, sexual violence and ill treatment in detention. -

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25

2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (OJ L 66, 10.3.2008, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 L 116 5 30.4.2008 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 L 108 20 29.4.2009 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 747/2009 of 14 August 2009 L 212 10 15.8.2009 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1267/2009 of 18 December 2009 L 339 24 22.12.2009 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 198, 26.7.2008, p. 74 (385/2008) 2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Articles 60 and 301 thereof, Having regard to Common Position 2007/750/CFSP of 19 November 2007 amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar (1), Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, Whereas: (1) On 28 October 1996, the Council, concerned at the absence of progress towards democratisation and at the continuing violation of human rights in Burma/Myanmar, imposed certain restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar by Common Position 1996/635/CFSP (2). -

Burma's Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy

Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy Updated May 17, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44804 Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy Summary Despite a campaign pledge that they “would not arrest anyone as political prisoners,” Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) have failed to fulfil this promise since they took control of Burma’s Union Parliament and the government’s executive branch in April 2016. While presidential pardons have been granted for some political prisoners, people continue to be arrested, detained, tried, and imprisoned for alleged violations of Burmese laws. According to the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma), or AAPP(B), a Thailand-based, nonprofit human rights organization formed in 2000 by former Burmese political prisoners, there were 331 political prisoners in Burma as of the end of April 2019. During its three years in power, the NLD government has provided pardons for Burma’s political prisoners on six occasions. Soon after assuming office in April 2016, former President Htin Kyaw and State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi took steps to secure the release of nearly 235 political prisoners. On May 23, 2017, former President Htin Kyaw granted pardons to 259 prisoners, including 89 political prisoners. On April 17, 2018, current President Win Myint pardoned 8,541 prisoners, including 36 political prisoners. In April and May 2019, he pardoned more than 23,000 prisoners, of which the AAPP(B) considered 20 as political prisoners. Aung San Suu Kyi and her government, as well as the Burmese military, however, also have demonstrated a willingness to use Burma’s laws to suppress the opinions of its political opponents and restrict press freedoms. -

Unlocking Civil Society and Peace in Myanmar

UNLOCKING CIVIL SOCIETY AND PEACE IN MYANMAR Opportunities, obstacles and undercurrents ABOUT THE COVER DESIGN: The cover design is a reflection of the dynamism of civil society in Myanmar, which is inherently complex, fluid, and interconnected. The bar charted along the outer circumference of the circle depicts the number of people working in each organisation. The inner lines meet when one of those people is engaged or connected with another organisation. The many crossings show how civil society interacts, networks, grows and expands. Alone they are each significant but together they make broad, impactful strokes. This visualisation was created using primary data collected throughout the research process for this Discussion Paper. CIVIL SOCIETY: A BRIDGE BETWEEN THE FAMILY & THE STATE FAMILY STATE RAPID GROWTH TRIGGERED BY TRANSITION & KEY EVENTS Cyclone Nargis 8888 Political Uprising 1980s 1990s 2000s 2010s EFFECTIVENESS IN KEY PEACEBUILDING FUNCTIONS Social Service Facilitation/ Socialisation Advocacy Protection Cohesion Monitoring Delivery Mediation Low Medium High ✁ CIVIL SOCIETY IN MYANMAR: TRENDS 1 2 3 NEW ORGANISATIONS REGISTRATION POLICY CSOs A boom in new CSOs More groups are Want to engage ocially registering more in policy 6 5 4 YOUTH GENDER NETWORKS Youth organisations are Women’s organisations are CSO’s build networks becoming more prominent advocating for gender participation 7 8 9 CEASEFIRES CROSSBORDER LITERATURE AND CULTURE Bi-lateral ceasefires Cross-border Groups that preserve transform relations organisations are -

Burma's Political Prisoners and US Policy: in Brief

Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy: In Brief name redacted Specialist in Asian Affairs June 6, 2017 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R44804 Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Policy: In Brief Summary With Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy (NLD) in control of Burma’s Union Parliament and the government’s executive branch, prospects may have improved for ending the arrest, detention, prosecution, and imprisonment of political prisoners in Burma, a reality which has overshadowed U.S. policy toward Burma for more than 25 years. Burma’s military, or Tatmadaw, however, may not support the unconditional release of all political prisoners in Burma, and potentially has the power to block such an effort. The 115th Congress may have an opportunity to influence Burma’s future efforts to address political prisoner issues. Whether by providing technical or other forms of assistance to address the underlying causes of political imprisonment, or by restricting relations with Burma until political prisoners have been released, Congress potentially could influence the behavior of the NLD-led government and the Tatmadaw with respect to political prisoners. According to the Assistance Association of Political Prisoners (Burma), or AAPP(B), a Thailand- based, nonprofit human rights organization formed in 2000 by former Burmese political prisoners, there were 305 political prisoners in Burma as of the end of April 2017. On the eve of Burma’s second “21st Century Peace Conference,” which brought together representatives of Aung San Suu Kyi’s government, the Burmese military and some of the nation’s ethnic armed groups in Naypiytaw, on May 24-29, 2017, President Htin Kyaw granted pardons to 259 prisoners, including 80 political prisoners. -

Surviving Sharks and Socialists

SURVIVING SHARKS AND SOCIALISTS SEPTEMBER 29, 2018 BLURRED IDENTITY Donor-conceived children wonder who their fathers are, and DNA testing is helping them find out OUTSOURCING LOVE LIVES CHINA’S CHRISTIAN SCHOOLS TO NORTH KOREA AND BACK A Biblical, non-insurance approach to health care Monthly costs: As believers in Christ, we are called to glorify God in all that we do. (Ranges based on age, household size, and membership level) Samaritan members bear each other’s burdens by sharing the cost of medical bills while praying for and encouraging one another. Members Individuals $100-$220 can choose between two membership options for sharing their medical 2 Person $200-$440 needs: Samaritan Classic and Samaritan Basic. 3+ People $250-$495 As of August 2018 Find more information at: samaritanministries.org/world CONTENTS | September 29, 2018 • Volume 33 • Number 18 30 17 38 42 50 FEATURES DISPATCHES 5 News Analysis • Human Race 30 Dear Anonymous Dad Quotables • Quick Takes Tens of thousands of children conceived by donors are grown up now and wondering who their fathers are. Advances in DNA CULTURE testing are helping them find out 17 Movies & TV • Books Children’s Books • Q&A • Music 38 Socialist seeds A socialist revolution may not be imminent in the United States, but NOTEBOOK the ideology is getting a surprising boost ahead of midterm elections 55 Lifestyle • Technology Science • Religion 42 Love life, outsourced As modern dating fails them, some singles are turning to VOICES professional matchmakers 3 Joel Belz 46 Hard tests for China’s