The Life and Writings of Harriett Mulford (Stone) Lothrop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University M crct. rrs it'terrjt onai A Be" 4 Howe1 ir”?r'"a! Cor"ear-, J00 Norte CeeD Road App Artjor mi 4 6 ‘Og ' 346 USA 3 13 761-4’00 600 sC -0600 Order Number 9238197 Selected literary letters of Sophia Peabody Hawthorne, 1842-1853 Hurst, Nancy Luanne Jenkins, Ph.D. -

Wayside, Minute Man National Historical Park, Historic Structure Report Part II, Historical Data Section

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2013 Wayside Minute Man National Historical Park Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Wayside Minute Man National Historical Park Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI) is an evaluated inventory of all significant landscapes in units of the national park system in which the National Park Service has, or plans to acquire any enforceable legal interest. Landscapes documented through the CLI are those that individually meet criteria set forth in the National Register of Historic Places such as historic sites, historic designed landscapes, and historic vernacular landscapes or those that are contributing elements of properties that meet the criteria. In addition, landscapes that are managed as cultural resources because of law, policy, or decisions reached through the park planning process even though they do not meet the National Register criteria, are also included in the CLI. The CLI serves three major purposes. First, it provides the means to describe cultural landscapes on an individual or collective basis at the park, regional, or service-wide level. Secondly, it provides a platform to share information about cultural landscapes across programmatic areas and concerns and to integrate related data about these resources into park management. Thirdly, it provides an analytical tool to judge accomplishment and accountability. The legislative, regulatory, and policy direction for conducting the CLI include: National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (16 USC 470h-2(a)(1)). -

Minute Man National Historic Park Case Study, Massachusetts Agriculture Experiment Station

NPS Form 10-900 ' KtUtlVED 2280 / ^-*QMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Int National Park Service National Register of Histc Registration Form ^"" fc This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete _^ National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable.: For functions, architectural classifications, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to compete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________^^^^^^ historic name Minute Man National Historical Park other names/site number n/a 2. Location street and number jyarious^__ _________ not for publication city or town Lexington, Lincoln, Concord___ _ (SI/A] vicinity state _ Massachusetts code MA county Middlesex code 017 zp 01742 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historjc Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ^ meets ____ does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant v" nationally _____ statewide ____ locally. -

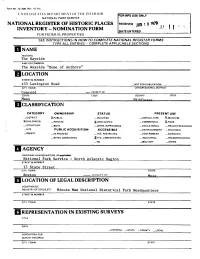

The Wayside ______AND/OR COMMON the Wayside "Home of Authors"______LOCATION

Form No 10-306 I Rev 10-74) UNITLDSTAThS DbPARTMbNT OHHMNItRlOR [FOR NFS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED JUJJ 1 9 1979 INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS__________ | NAME HISTORIC The Wayside _____________________________________ AND/OR COMMON The Wayside "Home of Authors"______________________________ LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 455 Lexington Road _ NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Concord — VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Mass M-iH^looo-u- Q CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _OISTRICT XPUBLIC _ OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE ?_MUSEUM X-BUILOING(S) _ PRIVATE XUNOCCUPIED _ COMMERCIAL X.PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT _ RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _|N PROCESS _YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED .gYES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _!NO _ MILITARY _ OTHER AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS National Park Service - North Atlantic Region STREET* NUMBER 15 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE BOStOn ———— VICINITY OF [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION Mace COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC Minute Man National Historical Park Headquarters STREET* NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE DATE —FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY TOWN i DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _ EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE .XGDOD RUINS JCALTERED _ FAIR _UNEX POSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Wayside, located on the north side of Route 2A, also known as "Battle Road," is part of Minute Man National Historical Park. The Wayside and its grounds extend just over four and a half acres and include the house, the barn, a well, a monument commemorating the centenary of Hawthorne's birth, and the remains of a slave's quarters. -

The Alcott Family

THE PATHETIC FAMILY • Mr. Amos Bronson Alcott born November 29, 1799 as Amos Bronson Alcox in Wolcott, Connecticut married May 23, 1830 in Boston to Abigail May, daughter of Colonel Joseph May died March 4, 1888 in Boston • Mrs. Abigail (May) “Abba” Alcott born October 8, 1800 in Boston, Massachusetts died November 25, 1877 in Concord, Massachusetts • Miss Anna Bronson Alcott born March 16, 1831 in Germantown, Pennsylvania married May 23, 1860 in Concord to John Bridge Pratt of Concord, Massachusetts died July 17, 1893 in Concord • Miss Louisa May Alcott born November 29, 1832 in Germantown, Pennsylvania died March 6, 1888 in Roxbury, Massachusetts • Miss Elizabeth Sewall Alcott born June 24, 1835 in Boston, Massachusetts died March 14, 1858 in Concord, Massachusetts • Abby May Alcott (Mrs. Ernest Niericker), born July 26, 1840 in Concord, married March 22, 1878 in London, England to Ernest Niericker, died December 29, 1879 in Paris “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project The Alcotts HDT WHAT? INDEX THE ALCOTTS THE PATHETIC FAMILY 1616 A family coat of arms was granted to Thomas Alcocke,1 made up of the device “three cocks emblematic of watchfulness,” and the motto “Semper vigilans”2 — which is an interesting aside on Thoreau’s use of Chanticleer in the epigraph for WALDEN; OR, LIFE IN THE WOODS, and his original desire to use a drawing of a rooster on the title page rather than a drawing of the cabin, for Amos Bronson Alcox would among others be a descendant of this Alcocke family and as the text makes clear, this older man had been a frequent visitor at the cabin and during this period had been a great influence upon Henry Thoreau. -

"Little Women" and "Five Little Peppers and How They Grew"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 Beneath the Umbrellas of Benevolent Men: Validation of the Middle-Class Woman in "Little Women" and "Five Little Peppers and How They Grew" Sandra Burr College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Burr, Sandra, "Beneath the Umbrellas of Benevolent Men: Validation of the Middle-Class Woman in "Little Women" and "Five Little Peppers and How They Grew"" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625669. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-m629-mw54 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BENEATH THE UMBRELLAS OF BENEVOLENT MENs VALIDATION OF THE MIDDLE-CLASS WOMAN IN LITTLE WOMEN AND FIVE LITTLE PEPPERS AND HOW THEY GREW A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Sandra Jeanne Burr 1991 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Sandra Jeanne Burr Approved r December 1991 Richard Lowry, Chair cj \n)Jh P.UW£ Walter P. Wenska Robert A. Gross 1 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am deeply grateful to Professor Rich Lowry for his acute perception and consistent good humor during the course of this study, and to Professors Walt Wenska and Bob Gross for their thoughtful observations and criticism. -

S Jochman Thesis (769.5Kb)

SCOPE FOR THE IMAGINATION: A LITERARY PILGRIMAGE TO THE LANDS OF LAURA INGALLS, PETER RABBIT, ANNE SHIRLEY, AND JO MARCH by Stefanie A. Jochman A Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts-English at The University of Wisconsin Oshkosh Oshkosh WI 54901-8621 May 2014 COMMITIEE APPROVAL DEAN OF GRADUATE STUDIES _~Ulti-Vl ~Vl1lU.. "-' _--=5~··-=.8_.. ..:.-1tt-'--__ Date Approved Date Approved -~---=~::::::~~~=.~~r==----- Member FORMAT APPROVAL <; ,t. \~ Date Approved ~~~,~S--'--~~~-=--Member- C;;. Z. i 4 Date Approved For my godparents, who introduced me to Laura, Peter, Anne, and Jo. For my mother, who always believed in her woman of words. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS On my journey from proposal to completed thesis I encountered many traveling companions worthy of thanks and recognition. First, I would like to thank my thesis director, Prof. Laura Jean Baker, a true kindred spirit, for making me a better, braver writer. I would also like to thank the other members of my thesis committee: Dr. Christine Roth, who shared an article on the serendipity of ―on location‖ research that inspired my project four years ago, and Prof. Douglas Haynes, whose Creative Nonfiction class offered an opportunity to explore the significance of place and nostalgia in my life. Simon Lloyd and the Special Collections staff at the Robertson Library of the University of Prince Edward Island were integral to my research on Anne of Green Gables tourism. Jan Turnquist and Lis Adams of Orchard House museum in Concord, Massachusetts, were warm and welcoming hosts for the 2013 Conversational Series. -

The American Novel Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture

A Companion to the American Novel Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture This series offers comprehensive, newly written surveys of key periods and movements and certain major authors, in English literary culture and history. Extensive volumes provide new perspectives and positions on contexts and on canonical and post-canonical texts, orientating the beginning student in new fields of study and providing the experienced undergraduate and new graduate with current and new directions, as pioneered and developed by leading scholars in the field. Published Recently 61. A Companion to Thomas Hardy Edited by Keith Wilson 62. A Companion to T. S. Eliot Edited by David E. Chinitz 63. A Companion to Samuel Beckett Edited by S. E. Gontarski 64. A Companion to Twentieth-Century United States Fiction Edited by David Seed 65. A Companion to Tudor Literature Edited by Kent Cartwright 66. A Companion to Crime Fiction Edited by Charles Rzepka and Lee Horsley 67. A Companion to Medieval Poetry Edited by Corinne Saunders 68. A New Companion to English Renaissance Literature and Culture Edited by Michael Hattaway 69. A Companion to the American Short Story Edited by Alfred Bendixen and James Nagel 70. A Companion to American Literature and Culture Edited by Paul Lauter 71. A Companion to African American Literature Edited by Gene Jarrett 72. A Companion to Irish Literature Edited by Julia M. Wright 73. A Companion to Romantic Poetry Edited by Charles Mahoney 74. A Companion to the Literature and Culture of the American West Edited by Nicolas S. Witschi 75. A Companion to Sensation Fiction Edited by Pamela K. -

Margaret Sidney and How She Grew

11-L6 164-H1)5v-11 O Margaret Sidney and How She Grew • Lisa M. Stepal3ki Professor Schrader Bibliography 9 Dec 1983 American children searching for interesting and entertain- ing literature in the mid 1800's were often confronted by dismal prospects. There was a surfeit of so-called "Sunday school books"— books distributed through Sunday schools--on the postiCivil Aai- marIcet. Yet these books were widely condemned for their gener- ally poor quality. One editor labelled them a "mass of trashy, diluted, unnatural books." It was not until the 1860's and 70's ,) that authors began writing realistic stories for children. One such author was Harriett Mulford Lothrop, better known as "Margaret Sidrie5i." She created the famous "Pepper" family--Ben, Polly, Joel, Davie, Phronsie, and Mrs. Pepper, or "Mamsie" as she was affection- ately called. Like the March family of Louisa May Alcott's beloved and highly successful Little Women (published 1868-9), the Peppers were a poor but stalwart family struggling to stay together. Per- haps inspired by Alcott's realism and energy, and aided by her own deep understanding of childrens' natures, matronly, patriotic Harriett Lothrop would write some of the most popular children's books of her day. p. 2 Stepanski She was born Harriett Mulford-Stone in New Haven,Connecticut ) on 22 June 1844. Young Harriett's lineage was indeed impressive-- on the paternal side she was an eighth generation descendant of Thomas Hooker, founder of Connecticut, whereas her mother, the daughter of a prominent New Haven shipowner and merchant, numbered Pilgrims of the Mayflower in her ancestry. -

Simon5, John4, Ebenezer3, John2

6-1 Sixth Generation Descendants of Simon5 & Mary (Wooley) Hartwell 6.1 JOHN6 HARTWELL (Simon5, John4, Ebenezer3, John2, William1) was born in Carlisle, Massachusetts 10 April 1753 (CVR 18) and died in Hillsborough, New Hampshire 17 October 1849, age 96 (Gs:Hillsborough Center Cemetery). He married 24 May 1774, SUSANNA FOSTER (HOA), who was born in Acton, Massachusetts 17 September 1753 (AVR 48) and died probably in Hills- borough 7 November 1815 (HOA), daughter of Hugh and Mary (Laws) Foster. In 1777, John bought of Jeremiah Green of Boston, Massachusetts for 18 pounds, a hundred acre tract in the northeast part of Hillsborough. He made annual trips to it on foot, as much as sixty miles, staying some weeks at a time, to clear a small field and build a log house. In 1780, with Thaddeus Monroe and Andrew Wilkins, he removed to the new home. The influx of many Concord, Massachusetts families gave the settlement the name of Concord End. According to Densmore, who remembered him as a 91 year old man still able to touch his chin with his toe, John was a man of cheerful disposition and sunny temperament, who retained his faculties almost unimpaired to the end. John is listed on the 1790 census as the head of a family in Hillsborough, consisting of one male over 16, two males under 16, and six females, which matches well with his known family at the time. Children, first two born in Concord, Massachusetts, rest in Hillsborough, New Hampshire: + 7.1 i. JOHN7 HARTWELL, b. 7 Nov 1774 (CBMD 243); m. -

BULLETIN, July, 2020

BULLETIN, July, 2020 UPCOMING IN THE LEXINGTON LEAGUE CARY LIBRARY PRESENTATIONS The physical re-opening date of Cary Memorial Library remains uncertain. However, the Library has arranged for virtual presentation of scheduled speakers of particular interest to League members, and the Lexington League will be co-sponsoring the following events: * > Victoria A. Budson: "The Essential Role of Women in Politics." Virginia Budson is the founder and Executive Director of the Women and Public Policy Program at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. She originated a training program which prepares women to run for public office and has trained graduate students from across the world. Institutions in many countries consult her training methodology to increase gender equity in their political leadership. Ms. Budson has provided consulting to the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development and Department of State, the White House Council on Women and Girls, and the U.S. Military, among others. This presentation, co-sponsored by the Lexington League and the Cary Library Foundation, will compare the level of participation of women and girls in the political process in the United States with that in other nations, and address the serious ramifications when women do not have "a seat at the table." The online program is scheduled for Thursday, July 23, from 7:00 pm to 8:30 pm, and requires advance registration, as space is limited. The Library will send out a program link by email on July 22. For more information contact [email protected]. -

Oric Houses Still in Concord

HISTORIC HOUSES STILL IN CONCORD October 21, Sunday: Henry Thoreau and his father John Thoreau had just had a conversation about the old houses in Concord: October 21: ... I have been thinking over with father the old houses in this street— There was the Hubbard (?) house at the fork of the roads—The Thayer (Bo house— (now Garrisons) The Sam Jones’s now Channings— Willoughby Prescots (a bevel roof— which I do not remember) where Lorings is— (Hoars was built by a Prescott)— Ma’m Bond’s. The Jones Tavern (Bigelow’s) The old Hurd (or Cumming’s?) house— The Dr Hurd House— The Old Mill—& The Richardson Tavern (which I do not remember— On this side— The Monroe house in which we lived —The Parkman House in which Wm Heywood 20 years ago told me^that he helped raise the rear of 60 years before—(it then sloping to one story behind) & that then it was called an old house Dr Ripley said that a Bond built it. The Merrick house— A rough-cast house where Bates’ is Betty—& all the S side of the mill dam— Still further from the center—the old houses & sites are about as numerous as above— Most of these houses— slanted to one story behind. OLD HOUSES “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY Traveling Much in Concord “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX TRAVELING MUCH IN CONCORD OLD HOMES 1644 The “Elisha Jones” house (also known as the home of Judge John Shepard Keyes) was being constructed as a two-story frame house with a side gable with triangular pediment entry portico.