S Jochman Thesis (769.5Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animated Stories by Beatrix Potter

The Brompton Tales Animated stories by Beatrix Potter Summary The Brompton Tales is a 14 part TV series that brings Beatrix Potter’s World of Peter Rabbit to life . Told to generations of children all over the world for the last century, these unique stories are wholesome and fun, yet they provide some valuable basic lessons for young children. Specs Over 45 millions copies of “The tale of Peter Rabbit” alone have been sold worldwide, Aspect Ratio together with numerous films and adaptations. Beatrix Potter’s stories are as loved today as 16 x 9 they were when first published over one hundred years ago. Resolution UHD Each episode is told by the enchanting voice of Perdita Avery. The story telling has been Framerate 3840 x 2160 kept true to the original text of the books with a few changes to some words that have 25fps lost their meaning over time in the modern english language. Perdita Avery’s voice is a Audio received pronunciation and very easy to understand. Bit Depth Stereo Each episode contains all of the drawings that feature in the books and are carefully brought Sample Rate 24 Bit to life with subtle animations to enhance the images and create movement all in stunning 48,000 Hz 4K. Format WAV (uncompressed) The most well known episode is of course “The Tale of Peter Rabbit”. The Tale of Peter Rabbit was first published by Frederick Warne in 1902 and endures as- Be atrix Potter’s most popular and well-loved tale. It tells the story of a very mischievous rabbit and the trouble he encounters in Mr McGregor’s vegetable garden! The series provides fourteen episodes that total run time of 145 minutes. -

The Lakes Tour 2015

A survey of the status of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2015 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, D. Ciar, M. Clarke, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, P. Keenan, E.B. Mackay, M. Patel, B. Tanna, I.J. Winfield Lake Ecosystems Group and Analytical Chemistry Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Lancaster UK & K. Bell, R. Clark, A. Jackson, J. Muir, P. Ramsden, J. Thompson, H. Titterington, P. Webb Environment Agency North-West Region, North Area History & geography of the Lakes Tour °Started by FBA in an ad hoc way: some data from 1950s, 1960s & 1970s °FBA 1984 ‘Tour’ first nearly- standardised tour (but no data on Chl a & patchy Secchi depth) °Subsequent standardised Tours by IFE/CEH/EA in 1991, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010 and most recently 2015 Seven lakes in the fortnightly CEH long-term monitoring programme The additional thirteen lakes in the Lakes Tour What the tour involves… ° 20 lake basins ° Four visits per year (Jan, Apr, Jul and Oct) ° Standardised measurements: - Profiles of temperature and oxygen - Secchi depth - pH, alkalinity and major anions and cations - Plant nutrients (TP, SRP, nitrate, ammonium, silicate) - Phytoplankton chlorophyll a, abundance & species composition - Zooplankton abundance and species composition ° Since 2010 - heavy metals - micro-organics (pesticides & herbicides) - review of fish populations Wastwater Ennerdale Water Buttermere Brothers Water Thirlmere Haweswater Crummock Water Coniston Water North Basin of Ullswater Derwent Water Windermere Rydal Water South Basin of Windermere Bassenthwaite Lake Grasmere Loweswater Loughrigg Tarn Esthwaite Water Elterwater Blelham Tarn Variable geology- variable lakes Variable lake morphometry & chemistry Lake volume (Mm 3) Max or mean depth (m) Mean retention time (day) Alkalinity (mequiv m3) Exploiting the spatial patterns across lakes for science Photo I.J. -

100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators

Page i 100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators Page ii POPULAR AUTHORS SERIES The 100 Most Popular Young Adult Authors: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. Revised First Edition. By Bernard A. Drew. Popular Nonfiction Authors for Children: A Biographical and Thematic Guide. By Flora R. Wyatt, Margaret Coggins, and Jane Hunter Imber. 100 Most Popular Children's Authors: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. By Sharron L. McElmeel. 100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators: Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies. By Sharron L. McElmeel. Page iii 100 Most Popular Picture Book Authors and Illustrators Biographical Sketches and Bibliographies Sharron L. McElmeel Page iv Copyright © 2000 Sharron L. McElmeel All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Libraries Unlimited, Inc. P.O. Box 6633 Englewood, CO 801556633 18002376124 www.lu.com Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data McElmeel, Sharron L. 100 most popular picture book authors and illustrators : biographical sketches and bibliographies / Sharron L. McElmeel. p. cm. — (Popular authors series) Includes index. ISBN 1563086476 (cloth : hardbound) 1. Children's literature, American—Biobibliography—Dictionaries. 2. Authors, American—20th century—Biography—Dictionaries. 3. Illustrators—United States—Biography—Dictionaries. 4. Illustration of books—Biobibliography—Dictionaries. 5. Illustrated children's books—Bibliography. 6. Picture books for children—Bibliography. I. Title: One hundred most popular picture book authors and illustrators. -

A Survey of the Lakes of the English Lake District: the Lakes Tour 2010

Report Maberly, S.C.; De Ville, M.M.; Thackeray, S.J.; Feuchtmayr, H.; Fletcher, J.M.; James, J.B.; Kelly, J.L.; Vincent, C.D.; Winfield, I.J.; Newton, A.; Atkinson, D.; Croft, A.; Drew, H.; Saag, M.; Taylor, S.; Titterington, H.. 2011 A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010. NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, 137pp. (CEH Project Number: C04357) (Unpublished) Copyright © 2011, NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology This version available at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/14563 NERC has developed NORA to enable users to access research outputs wholly or partially funded by NERC. Copyright and other rights for material on this site are retained by the authors and/or other rights owners. Users should read the terms and conditions of use of this material at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/policies.html#access This report is an official document prepared under contract between the customer and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without the permission of both the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the customer. Contact CEH NORA team at [email protected] The NERC and CEH trade marks and logos (‘the Trademarks’) are registered trademarks of NERC in the UK and other countries, and may not be used without the prior written consent of the Trademark owner. A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, H. Feuchtmayr, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, J.L. Kelly, C.D. -

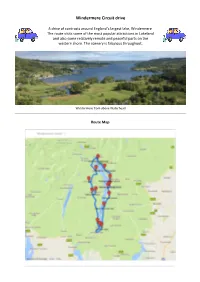

Windermere Circuit Drive

Windermere Circuit drive A drive of contrasts around England’s largest lake, Windermere. The route visits some of the most popular attractions in Lakeland and also some relatively remote and peaceful parts on the western shore. The scenery is fabulous throughout. Windermere from above Waterhead Route Map Summary of main attractions on route (click on name for detail) Distance Attraction Car Park Coordinates 0 miles Waterhead, Ambleside N 54.42116, W 2.96284 2.1 miles Brockhole Visitor Centre N 54.40120, W 2.93914 4.3 miles Rayrigg Meadow picnic site N 54.37897, W 2.91924 5.3 miles Bowness-on-Windermere N 54.36591, W 2.91993 7.6 miles Blackwell House N 54.34286, W 2.92214 9.5 miles Beech Hill picnic site N 54.32014, W 2.94117 12.5 miles Fell Foot park N 54.27621, W 2.94987 15.1 miles Lakeside, Windermere N 54.27882, W 2.95697 15.9 miles Stott Park Bobbin Mill N 54.28541, W 2.96517 21.0 miles Esthwaite Water N 54.35029, W 2.98460 21.9 miles Hill Top, Near Sawrey N 54.35247, W 2.97133 24.1 miles Hawkshead Village N 54.37410, W 2.99679 27.1 miles Wray Castle N 54.39822, W 2.96968 30.8 miles Waterhead, Ambleside N 54.42116, W 2.96284 The Drive Distance: 0 miles Location: Waterhead car park, Ambleside Coordinates: N 54.42116, W 2.96284 Slightly south of Ambleside town, Waterhead has a lovely lakeside setting with plenty of attractions. Windermere lake cruises call at the jetty here and it is well worth taking a trip down the lake to Bowness or even Lakeside at the opposite end of the lake. -

Issue 130 (April 200

26 The 2005 Elian Birthday Toast By DICK WATSON The 2005 Elian Birthday Toast was held on Saturday, 19 February at the Royal College of General Practitioners, South Kensington, London ON AN OCCASION SUCH AS A BIRTHDAY LUNCH, it is natural to think of anniversaries. It is this which was in my mind when I reflected that exactly two hundred years ago, to the day, on 19 February 1805, Charles Lamb was writing to William Wordsworth. It was the second letter in two days, referring to the death of Wordsworth’s brother John in the shipwreck of the Earl of Abergavenny off Portland. It was an event which affected the poet, and indeed the whole family, very deeply, and which was only partially resolved in the ‘Elegiac Stanzas’ which Wordsworth wrote after seeing Sir George Beaumont’s picture of Peele Castle in a Storm. As Richard E. Matlak has shown in Deep Distresses, John Wordsworth had, by dint of hard work and good conduct, risen to become the captain of an East Indiaman. A captain in such a position stood to gain much from a voyage, and John had hoped to get enough money to set the family up in comfort. He required capital from the venture, and both William and Dorothy invested money in it. The ship set sail from Portsmouth on 1 February, and ran into bad weather. The pilot tried to run for shelter, but the ship struck a rock at four o’clock in the afternoon of 5 February. According to one account, John Wordsworth is supposed to have said, ‘Oh Pilot! Pilot! You have ruined me!’ Some of the crew and passengers got ashore in boats, but of the 402 passengers on board only 100 were saved. -

Find Book ^ the Tale of Two Bad Mice (Hardback)

OOCPF6VPGWW0 PDF > The Tale of Two Bad Mice (Hardback) Th e Tale of Two Bad Mice (Hardback) Filesize: 1.49 MB Reviews This is the very best pdf i actually have study right up until now. I could possibly comprehended almost everything using this created e book. Your daily life span will be enhance as soon as you total looking over this publication. (Prof. Johnson Rutherford) DISCLAIMER | DMCA PWATJDBHJ5Y3 ~ Kindle « The Tale of Two Bad Mice (Hardback) THE TALE OF TWO BAD MICE (HARDBACK) Penguin Books Ltd, United Kingdom, 2012. Hardback. Condition: New. 110th Anniversary ed.. Language: English . Brand New Book. It s been 110 years since Frederick Warne published Beatrix Potter s very first book, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, and in celebration, we are delighted to be publishing special editions of her entire body of work. Unlike the traditional little white books, these editions have delightful colourful covers and specially designed endpapers. And to make them extra special, we have included a publisher s note to tell you all about the history of how each book came to be. When two naughty little mice discover the door to the beautiful doll s house ajar, they just have to tiptoe inside and have a look. The temptation to try the delicious looking food in the dining room proves too great however, and chaos ensues when they discover that it will not come o the plates!The Tale of Two Bad Mice is number five in Beatrix Potter s series of 23 little books. Read The Tale of Two Bad Mice (Hardback) Online Download PDF The Tale of Two Bad Mice (Hardback) 7BXBEIZAZMJQ \\ eBook ~ The Tale of Two Bad Mice (Hardback) Relevant PDFs The Country of the Pointed Firs and Other Stories (Hardscrabble Books-Fiction of New England) New Hampshire. -

Cumulative Index 91-100

Cumulative Index to The Beatrix Potter Society Newsletters, Numbers 91 – 100 Compiled by Rowena Godfrey In this index, Beatrix Potter’s name has been abbreviated to BP, apart from the entry Potter, Helen Beatrix. For individual manufacturers of merchandise, see under Merchandise. Adult BP programs 93:15; see also Introducing BP project Akester, Jenny (Committee, Membership; Conference Organiser) 93:2; 94:7, 12, 16 ‘Adopt-a-Potter!’ 98:27 ‘A week in the life of a volunteer’ 100:40 Report on the Eleventh International Study Conference 94:11 ‘Skink!! For dinner? Surely not!’ 95:30 Alderson, Brian (President) 91:27 Review of Cotsen Occasional Press books 98:23 Alderson, Valerie (President’s wife) 94:37; 97:39 Angel, Marie (illustrator) 100:33, 34 Annual General Meetings reports on – 2004 92:Appendix, 5; 2005 96:Appendix, 6; 2006 100:Appendix, 7 ‘Antiques Roadshow’ (BBC television programme) 91:12; 92:20; 96:17 Antiques Trade Gazette (UK trade magazine) 95:31 Appleby (headquarters of the Heelis firm) 95:26 Appley Dapply’s Nursery Rhymes (BP) 98:25 Aris, Ernest A. (artist, writer and illustrator) 94:38 Armitt Trust; see also Exhibitions ‘BP: Gardener’; Lakes Discovery Museum @ the Armitt, The Museum and Library 92:23, 33; 93:2; 94:4; 100:38 Art of BP, The (L. Linder) 92:32; 95:21; 98:4 Art Nouveau 95:10 Arts and Crafts Movement 99:6 Arundel Castle (Sussex) 100:25 Ashyburn Farm (Bertram Potter’s home in Scotland) 94:26 Austin, Mike (Sales Manager and Committee, Treasurer) C.V. 93:3 Austin, Patricia (Sales Manager) ‘Collectors’ Corner’ (with -

Historical Places of Peace in British Literature Erin Kayla Choate Harding University, [email protected]

Tenor of Our Times Volume 4 Article 7 Spring 2015 "My Own Little omeH ": Historical Places of Peace in British Literature Erin Kayla Choate Harding University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, History Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Choate, Erin Kayla (Spring 2015) ""My Own Little omeH ": Historical Places of Peace in British Literature," Tenor of Our Times: Vol. 4, Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor/vol4/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Scholar Works at Harding. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tenor of Our Times by an authorized editor of Scholar Works at Harding. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “MY OWN LITTLE HOME”: HISTORICAL PLACES OF PEACE IN BRITISH LITERATURE By Erin Kayla Choate Kenneth Grahame, Beatrix Potter, and Alan Alexander Milne were three children’s authors living between 1859 and 1956 who wrote stories revolving around a sense of what can be called a place of peace. Each one’s concept of peace was similar to the others. Grahame voiced it as “my own little home” through his character Mole in The Wind in the Willows.1 Potter expressed it through the words “at home in his peaceful nest in a sunny bank” in her book The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse.2 Finally, Milne described it in The House at Pooh Corner as “that enchanted -

Gifts for Book Lovers HAPPY NEW YEAR to ALL OUR LOVELY

By Appointment To H.R.H. The Duke Of Edinburgh Booksellers Est. 1978 www.bibliophilebooks.com ISSN 1478-064X CATALOGUE NO. 338 JAN 2016 78920 ART GLASS OF LOUIS COMFORT TIFFANY Inside this issue... ○○○○○○○○○○ by Paul Doros ○○○○○○○○○○ WAR AND MILITARIA The Favrile ‘Aquamarine’ vase of • Cosy & Warm Knits page 10 1914 and the ‘Dragonfly’ table lamp are some of the tallest and most War is not an adventure. It is a disease. It is astonishingly beautiful examples of • Pet Owner’s Manuals page 15 like typhus. ‘Aquamarine’ glass ever produced. - Antoine de Saint-Exupery The sinuous seaweed, the • numerous trapped air bubbles, the Fascinating Lives page 16 varying depths and poses of the fish heighten the underwater effect. See pages 154 to 55 of this • Science & Invention page 13 78981 AIR ARSENAL NORTH glamorous heavyweight tome, which makes full use of AMERICA: Aircraft for the black backgrounds to highlight the luminescent effects of 79025 THE HOLY BIBLE WITH Allies 1938-1945 this exceptional glassware. It is a definitive account of ILLUSTRATIONS FROM THE VATICAN Gifts For Book by Phil Butler with Dan Louis Comfort Tiffany’s highly collectable art glass, Hagedorn which he considered his signature artistic achievement, LIBRARY $599.99 NOW £150 Lovers Britain ran short of munitions in produced between the 1890s and 1920s. Called Favrile See more spectacular images on back page World War II and lacked the dollar glass, every piece was blown and decorated by hand. see page 11 funds to buy American and The book presents the full range of styles and shapes Canadian aircraft outright, so from the exquisite delicacy of the Flowerforms to the President Roosevelt came up with dramatically dripping golden flow of the Lava vases, the idea of Lend-Lease to assist the from the dazzling iridescence of the Cypriote vases to JANUARY CLEARANCE SALE - First Come, First Served Pg 18 Allies. -

THE BEATRIX POTTER COLLECTION Tracks

Helen Beatrix Potter was born on 28 July, 1866 to a comfortable upper middle- class British family. She grew up isolated from other children. She rarely saw her brother, who was sent to boarding school, while Beatrix was educated at home, by governesses. Although she was quite shy, she was a very creative girl, encouraged by her parents and governesses who taught her to paint and draw. In 1902, at the age of 36, Beatrix Potter published The Tale of Peter Rabbit , and became secretly engaged to her publisher, Norman Warne. This caused a breach with her parents, who disapproved of her marrying someone they believed was of lower social status. Warne died before the wedding could take place. The success of her children's books allowed her to become financially independent of her parents. She purchased a farm, Hill Top, near Sawry in England's Lake District. Over time, she extended her land holdings. Beatrix Potter died on 22 December 1943. ______________________________ ______________________________ THE BEATRIX POTTER Tracks COLLECTION Shorter tales for younger listeners Longer tales for older listeners The Tale of Peter Rabbit a01 The Tailor of Gloucester c01a – c The Tale of Two Bad Mice a02 The Tale of Samuel Whiskers or c02a – c The Roly-Poly Pudding The Tale of Mr Jeremy Fisher a03 The Story of a Fierce Bad Rabbit a04 The Tale of Pigling Bland c03a – d The Story of Miss Moppett a05 The Tale of Mr Tod c04a – e The Tale of Tom Kitten a06 Total running time: 4 hours The Tale of Benjamin Bunny a07 The Tale of the Flopsy Bunnies a08 Apply Dappley’s Nursery Rhymes a09 Cecily Parsley’s Nursery Rhymes a10 The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin b01 The Tale of Mrs Tiggy-Winkle b02 www.sodyaudio.com The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck b03 Ginger and Pickles b04 The Tale of Mrs Tittlemouse b05 Narrated and produced by Shane Sody The Tale of Timmy Tiptoes b06 Recordings 2009 Shane Sody The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse b07 (Sody Audio Books) The Pie and the Patty-Pan b08a & b . -

Heterogeneity in Esthwaite Water, a Small, Temperate Lake: Consequences for Phosphorus Budgets

Heterogeneity in Esthwaite Water, a Small, Temperate Lake: Consequences for Phosphorus Budgets Eleanor B. Mackay BSc. MSc. Lancaster Environment Centre Lancaster University Submitted to Lancaster University for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2011 ProQuest Number: 11003693 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003693 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Declaration I declare that this thesis is entirely my own work and has not been submitted for a higher degree at another institution or university. < Signed Date. \3rA\../2pi Abstract Eutrophication through phosphorus enrichment of lakes is potentially damaging to lake ecosystems, water quality and the ecosystem services which they provide. Traditional approaches to managing eutrophication involve quantifying phosphorus budgets. An important shortcoming of these approaches is that they take little account of the inherent heterogeneity of lakes. Furthermore, most studies of lake heterogeneity have been carried out in large lakes, a situation which reflects neither small lakes’ importance in biogeochemical cycling nor their significant contribution to the global sum of lake environments.