Issue 130 (April 200

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The River Duddon (End Underline)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2007-11-29 Wordsworth's Evolving Project: Nature, the Satanic School, and (underline) The River Duddon (end underline) Kimberly Jones May Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation May, Kimberly Jones, "Wordsworth's Evolving Project: Nature, the Satanic School, and (underline) The River Duddon (end underline)" (2007). Theses and Dissertations. 1247. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/1247 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. WORDSWORTH’S EVOLVING PROJECT: NATURE, THE “SATANIC SCHOOL,” AND THE RIVER DUDDON by Kimberly Jones May A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English Brigham Young University December 2007 BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COMMITTEE APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Kimberly Jones May This thesis has been read by each member of the following graduate committee and by majority vote has been found to be satisfactory. November 16, 2007 Date Nicholas Mason, Chair November 16, 2007 Date Dan Muhlestein, Reader November 16, 2007 Date Matthew Wickman, Reader -

The Lakes Tour 2015

A survey of the status of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2015 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, D. Ciar, M. Clarke, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, P. Keenan, E.B. Mackay, M. Patel, B. Tanna, I.J. Winfield Lake Ecosystems Group and Analytical Chemistry Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Lancaster UK & K. Bell, R. Clark, A. Jackson, J. Muir, P. Ramsden, J. Thompson, H. Titterington, P. Webb Environment Agency North-West Region, North Area History & geography of the Lakes Tour °Started by FBA in an ad hoc way: some data from 1950s, 1960s & 1970s °FBA 1984 ‘Tour’ first nearly- standardised tour (but no data on Chl a & patchy Secchi depth) °Subsequent standardised Tours by IFE/CEH/EA in 1991, 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010 and most recently 2015 Seven lakes in the fortnightly CEH long-term monitoring programme The additional thirteen lakes in the Lakes Tour What the tour involves… ° 20 lake basins ° Four visits per year (Jan, Apr, Jul and Oct) ° Standardised measurements: - Profiles of temperature and oxygen - Secchi depth - pH, alkalinity and major anions and cations - Plant nutrients (TP, SRP, nitrate, ammonium, silicate) - Phytoplankton chlorophyll a, abundance & species composition - Zooplankton abundance and species composition ° Since 2010 - heavy metals - micro-organics (pesticides & herbicides) - review of fish populations Wastwater Ennerdale Water Buttermere Brothers Water Thirlmere Haweswater Crummock Water Coniston Water North Basin of Ullswater Derwent Water Windermere Rydal Water South Basin of Windermere Bassenthwaite Lake Grasmere Loweswater Loughrigg Tarn Esthwaite Water Elterwater Blelham Tarn Variable geology- variable lakes Variable lake morphometry & chemistry Lake volume (Mm 3) Max or mean depth (m) Mean retention time (day) Alkalinity (mequiv m3) Exploiting the spatial patterns across lakes for science Photo I.J. -

A Survey of the Lakes of the English Lake District: the Lakes Tour 2010

Report Maberly, S.C.; De Ville, M.M.; Thackeray, S.J.; Feuchtmayr, H.; Fletcher, J.M.; James, J.B.; Kelly, J.L.; Vincent, C.D.; Winfield, I.J.; Newton, A.; Atkinson, D.; Croft, A.; Drew, H.; Saag, M.; Taylor, S.; Titterington, H.. 2011 A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010. NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, 137pp. (CEH Project Number: C04357) (Unpublished) Copyright © 2011, NERC/Centre for Ecology & Hydrology This version available at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/14563 NERC has developed NORA to enable users to access research outputs wholly or partially funded by NERC. Copyright and other rights for material on this site are retained by the authors and/or other rights owners. Users should read the terms and conditions of use of this material at http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/policies.html#access This report is an official document prepared under contract between the customer and the Natural Environment Research Council. It should not be quoted without the permission of both the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the customer. Contact CEH NORA team at [email protected] The NERC and CEH trade marks and logos (‘the Trademarks’) are registered trademarks of NERC in the UK and other countries, and may not be used without the prior written consent of the Trademark owner. A survey of the lakes of the English Lake District: The Lakes Tour 2010 S.C. Maberly, M.M. De Ville, S.J. Thackeray, H. Feuchtmayr, J.M. Fletcher, J.B. James, J.L. Kelly, C.D. -

Abbreviations Used in the Notes

ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE NOTES The following list is for use in connection with the short-form citations in Notes to the Introduction (beginning at p. 148 below) and Notes to the Poems (beginning at p. 150 below). BL S. T. Coleridge, Biographia Literaria, 2 vols (London, 1817); ed. J. Shawcross, 2 vols (Oxford, 1907). EY The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth: The Early Years, 1787-1805, ed. Ernest de Selincourt (Oxford, 1935); 2nd edn rev. Chester L. Shaver (Oxford, 1967). See also LY and MY, below. HD William Wordsworth, Poems in Two Volumes, ed. Helen Darbishire (Oxford, 1914; 2nd edn, 1952). Hutchinson William Wordsworth, Poems in Two Volumes, ed. Thomas Hutchinson, 2 vols (London, 1897). IF Notes dictated by Wordsworth to Isabella Fenwick. JDW Journals of Dorothy Wordsworth, ed. Mary Moorman (Oxford, 1971) - notably the Alfoxden and Grasmere Journals. LSTC Collected Letters of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. E. L. Griggs, 6 vols (Oxford, 1956-71). LY I, II The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth: The Later Years, 1821-1834, ed. Ernest de Selincourt (Oxford, 1938-9); 2nd edn rev. Alan G. Hill (Oxford, 1978-9). See also EY above, and MY below. MS.L. Longman MS, British Library Add. MS. 47864. [Cf. A Description of the Wordsworth and Coleridge Manuscripts in the Possession of Mr T. Norton Longman, ed. W. Hale White (London, 1897).] MYI The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth: The Middle Years, Part I, 1806-1811, ed. Ernest de Selincourt (Oxford, 1936); 2nd edn rev. Mary Moorman (Oxford, 1969). MY II The Letters of William and Dorothy Wordsworth: The Middle Years, Part II, 1812-1820, ed. -

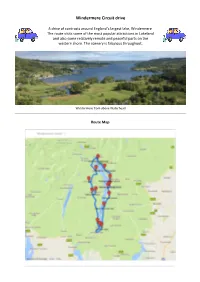

Windermere Circuit Drive

Windermere Circuit drive A drive of contrasts around England’s largest lake, Windermere. The route visits some of the most popular attractions in Lakeland and also some relatively remote and peaceful parts on the western shore. The scenery is fabulous throughout. Windermere from above Waterhead Route Map Summary of main attractions on route (click on name for detail) Distance Attraction Car Park Coordinates 0 miles Waterhead, Ambleside N 54.42116, W 2.96284 2.1 miles Brockhole Visitor Centre N 54.40120, W 2.93914 4.3 miles Rayrigg Meadow picnic site N 54.37897, W 2.91924 5.3 miles Bowness-on-Windermere N 54.36591, W 2.91993 7.6 miles Blackwell House N 54.34286, W 2.92214 9.5 miles Beech Hill picnic site N 54.32014, W 2.94117 12.5 miles Fell Foot park N 54.27621, W 2.94987 15.1 miles Lakeside, Windermere N 54.27882, W 2.95697 15.9 miles Stott Park Bobbin Mill N 54.28541, W 2.96517 21.0 miles Esthwaite Water N 54.35029, W 2.98460 21.9 miles Hill Top, Near Sawrey N 54.35247, W 2.97133 24.1 miles Hawkshead Village N 54.37410, W 2.99679 27.1 miles Wray Castle N 54.39822, W 2.96968 30.8 miles Waterhead, Ambleside N 54.42116, W 2.96284 The Drive Distance: 0 miles Location: Waterhead car park, Ambleside Coordinates: N 54.42116, W 2.96284 Slightly south of Ambleside town, Waterhead has a lovely lakeside setting with plenty of attractions. Windermere lake cruises call at the jetty here and it is well worth taking a trip down the lake to Bowness or even Lakeside at the opposite end of the lake. -

Historical Places of Peace in British Literature Erin Kayla Choate Harding University, [email protected]

Tenor of Our Times Volume 4 Article 7 Spring 2015 "My Own Little omeH ": Historical Places of Peace in British Literature Erin Kayla Choate Harding University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, History Commons, and the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Choate, Erin Kayla (Spring 2015) ""My Own Little omeH ": Historical Places of Peace in British Literature," Tenor of Our Times: Vol. 4, Article 7. Available at: https://scholarworks.harding.edu/tenor/vol4/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Humanities at Scholar Works at Harding. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tenor of Our Times by an authorized editor of Scholar Works at Harding. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “MY OWN LITTLE HOME”: HISTORICAL PLACES OF PEACE IN BRITISH LITERATURE By Erin Kayla Choate Kenneth Grahame, Beatrix Potter, and Alan Alexander Milne were three children’s authors living between 1859 and 1956 who wrote stories revolving around a sense of what can be called a place of peace. Each one’s concept of peace was similar to the others. Grahame voiced it as “my own little home” through his character Mole in The Wind in the Willows.1 Potter expressed it through the words “at home in his peaceful nest in a sunny bank” in her book The Tale of Johnny Town-Mouse.2 Finally, Milne described it in The House at Pooh Corner as “that enchanted -

William Wordsworth (7 A;뼈 1770 - 23 Ap벼 1850)

William Wordsworth (7 A;뼈 1770 - 23 Ap벼 1850) Judith W. Page Millsaps College BOOKS: AnEv’e1’↑따r Peter Bell, A Tale in Verse (London: Printed by dressed to a young Lady, [rom the Lakes o[ the Strahan & Spottiswoode for Longman, North o[ Englaηd (London: Printed for J. Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1819); johnson, 1793); The Waggoner, A Poem. To Which are added, Sonnets Descriptive Sketches. ln Verse. Take'ft 4t띠ng a Pedes (London: Printed by Strahan & Spot trian Tour in the ltalian, G:매:son, Swi:ss, and Sa tiswoode for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme voyard Aφ's (London: Printed for J. johnson, & Brown, 1819); 1793); M강cellaη eous Poems o[ William Word:sworth, 4 vol Lyrical Ballad:s, with a [ew other Poems (Bristol: umes (London: Printed for Longman, Printed by Biggs & Cottle for T. N. Long Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1820); man, London, 1798; London: Printed for J. The River Dμddoη, A se얘es o[ Sonnets: Vaudracmιr & A. Arch 1798; enlarged edition 2 vol , , q,nd Jμ lia: and Other Poems. To which 강 aη umes, London: Printed for T. N. Longman nexed, A Topographical Desc얘 tioη o[ the Coun & Rees by Biggs &. Co., Bristol, 1800; Phil o. tη, o[ the Lakes, in the North o[ Eη.glaηd (Lon adelphia: Printed & s이d by james Hum don: Printed for Longman, Hursì:, Rees, phreys, 1802); Orme & Brown, 1820); Poems, in two Volumes (London: Printed for Long ADαcπÖ:þ tioη o[ the Sceη ery o[ the Lakes in The N orth man, Hurst, Rees & Orm~ , 1807); o[ Eη.glaηd. Third Editioη, (Now [irst publi:shed Concerning the Convention o[ Cintra (London: separately) (London: Printed for Longman, Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees & Orme Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1822; revised 1809); and enlarged, 1823); revised and enlarged TheEχ:cursion, being a portion o[ The Recluse, a Poem again as A Gμide through the Di:strict o[ the (London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Lakes in The N orth o[ Eηgland (Kendal: Pub Rees, Orme & Brown, 1814; New York: C. -

1 Essay Title: Romantic Poetry and Victorian

Essay title: Romantic Poetry and Victorian Nonsense Poetry: Some Directions of Travel Name: Peter Swaab Email: [email protected] Postal address: Dept of English, UCL, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT Abstract: This essay explores links between Victorian nonsense poetry and poetry of the Romantic period, with a focus on narratives of quest, voyaging and escape. It discusses brief instances from various writers of the two periods and moves on to a more developed comparison between Wordsworth and Edward Lear, centring on ‘The Blind Highland Boy’. The comparison between periods leads to an argument that self- critique and scepticism were quite robustly in place from the start in the romantic period, and that obstacles to sense could at times be experienced not just as perplexity but as enjoyment shared with an audience. It also points to a further appreciation of some of the less canonical works by the most canonical writers, and suggests a tradition in which romantic aspiration was often coolly linked to a sense of absurdity. Keywords: romanticism, nonsense poetry, quests, voyages, romantic Victorianism 1 Romantic Poetry and Victorian Nonsense Poetry: Some Directions of Travel Peter Swaab We are used to asking what was Victorian about nonsense writing, but this essay takes the slightly different approach of asking what was Romantic about it. Various thematic and generic links suggest themselves as possible approaches. First, we might say that nonsense brings a cooling comic self-consciousness to many of the dramas of romanticism – for instance those involving childhood, isolation, utopian dreams, travel and imperialism. In exploring sublimity, nonsense always grounds it in absurdity, chiefly the absurdity of love in Edward Lear, and of meaning in Lewis Carroll. -

Arnold, Matthew, 99 Barrett Browning, Elizabeth, 99 Battle of Waterloo, 30

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-89668-9 - The Cambridge Introduction to William Wordsworth Emma Mason Index More information Index Arnold, Matthew, 99 ecopoetics, 110 elegy, 57–60 Barrett Browning, Elizabeth, 99 Eliot, George, 99 Battle of Waterloo, 30 Emerson, Ralph Waldo, 20 Beaumont, George, 11, 21 emotion, 23, 37, 39, 43, 45, 47, 68, 77, Beaupuy, Michael, 4 79, 110 Bible, 40, 41, 54, 100, 102 enclosure, 29 Ecclesiastes, 92 Enlightenment, the 24 Genesis, 81 environmentalism, 110 Gospel of Luke, 83 epitaphs, 59 Gospel of Mark, 92 ethical criticism, 109–10 Psalms, 77, 92 Evangelical Revival, 40, 41 Revelation, 54 Blake, William, 99 Fenwick, Isabella, 21, 52, 86, 105 blank verse, 49–52 formalism, 107–8 Bonaparte, Napoleon, 32 Fox, Charles James, 34, 36, 51, 82 Burke, Edmund, 4, 26, 28, 32, 36 French Revolution, 4, 30, 37 capitalism, 27 Gaskell, Elizabeth, 99 Church of England, 18, 19, 41, gender, 103–6 42, 43, 93 Godwin, William, 6, 33, 66 Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, xi, xii, xv, 7, Gordon Riots, 30 11, 14, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21, 25, 33, Grasmere, 9 34, 38, 41, 51, 53, 70, 71, 78, 89, graveyard poets, 57 92, 105, 124 Greenwell, Dora, 100 ‘Christabel’, 71 fancy, 90 Habermas, Jürgen, 26 ‘The Rime of the Ancyent Hartley, David, 24 Marinere’, 70, 71 Hawkshead, 2, 58 community, 37, 47, 109 Hazlitt, William, 46, 99 Hemans, Felicia, 19, 54, De Quincey, Thomas,13 , 14, 68 99, 104 deconstruction, 103 historicism, 106 dissenting academies, 25 Hopkins, Gerard Manley, 100 dissenting religion, 41 Hume, David, 26 131 © in this web service Cambridge -

Heterogeneity in Esthwaite Water, a Small, Temperate Lake: Consequences for Phosphorus Budgets

Heterogeneity in Esthwaite Water, a Small, Temperate Lake: Consequences for Phosphorus Budgets Eleanor B. Mackay BSc. MSc. Lancaster Environment Centre Lancaster University Submitted to Lancaster University for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2011 ProQuest Number: 11003693 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003693 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Declaration I declare that this thesis is entirely my own work and has not been submitted for a higher degree at another institution or university. < Signed Date. \3rA\../2pi Abstract Eutrophication through phosphorus enrichment of lakes is potentially damaging to lake ecosystems, water quality and the ecosystem services which they provide. Traditional approaches to managing eutrophication involve quantifying phosphorus budgets. An important shortcoming of these approaches is that they take little account of the inherent heterogeneity of lakes. Furthermore, most studies of lake heterogeneity have been carried out in large lakes, a situation which reflects neither small lakes’ importance in biogeochemical cycling nor their significant contribution to the global sum of lake environments. -

FRESHWATER BIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION the Ferry House, Ambleside, Cumbria, LA22 OLP UK Bassenthwaite Lake

Bassenthwaite Lake: a general assessment of environmental and biological features and their susceptibility to change Item Type monograph Authors Atkinson, K.M.; Heaney, S.I.; Elliott, J.M.; Mills, C.A. Publisher Freshwater Biological Association Download date 26/09/2021 22:37:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/22763 FRESHWATER BIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION The Ferry House, Ambleside, Cumbria, LA22 OLP UK Bassenthwaite Lake: a general assessment of environmental and biological features and their susceptibility to change K.M. Atkinson S.I. Heaney J.M. Elliott C.A. Mills J.F. Talling (editor) Project Leader: C . A . Mills Contract No: T04040-5A Report Date: March 1989 FBA Report Ref. No: WI/T04040/1 Report To: North West Water TFS Project No: T04040-5A This is an unpublished report and should not be cited without permission. Publication rights to original data are reserved by the F.B.A. The Freshwater Biological Association is part of the Terrestrial and Freshwater Sciences Directorate of the Natural Environment Research Council. CONTENTS Page 1 . Introduction (J.F. Talling) 1 2 . Physical features (J.F. Talling) 2 3 . Chemical information (J.F. Talling) 4 3.1 Historical 4 3.2 Detailed study of 1987-8 5 3.3 Implications 8 4. Phytoplankton (S.I. Heaney) 9 4.1 Historical 9 4.2 Study of 1987-8 10 4.3 Implications 11 5. Zooplankton (S.I. Heaney) 12 5.1 Historical 12 5. 2 Study of 1986-8 12 5.3 Implications 13 6. Bottom fauna (J.M. Elliott) 13 6.1 Historical 13 6.2 Study of 1987-8 14 6.3 Implications 15 7. -

The Poems of William Wordsworth Collected Reading Texts from the Cornell Wordsworth

The Poems of William Wordsworth Collected Reading Texts from The Cornell Wordsworth Edited by Jared Curtis In Three Volumes A Complimentary Addendum HEB ☼ Humanities-Ebooks For advice on use of this ebook please scroll to page 2 Using this Ebook t * This book is designed to be read in single page view, using the ‘fit page’ command. * To navigate through the contents use the hyperlinked ‘Bookmarks’ at the left of the screen. * To search, click the search symbol. * For ease of reading, use <CTRL+L> to enlarge the page to full screen, and return to normal view using < Esc >. * Hyperlinks (if any) appear in Blue Underlined Text. Permissions You may print a copy of the book for your own use but copy and paste functions are disabled. No part of this publication may be otherwise reproduced or transmitted or distributed without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher. Making or distributing copies of this book would constitute copyright infringement and would be liable to prosecution. Thank you for respecting the rights of the author. An Addendum to The Poems of William Wordsworth Collected Reading Texts from The Cornell Wordsworth Series In Three Volumes Edited by Jared Curtis HEB ☼ Humanities-Ebooks, LLP © Jared Curtis, 2012 The Author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published by Humanities-Ebooks, LLP, Tirril Hall, Tirril, Penrith CA10 2JE. Cover image, Sunburst over Martindale © Richard Gravil The reading texts of Wordsworth’s poems used in this volume are from the Cornell Wordsworth series, published by Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, NY 14850.