Tamaira, 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawaiian Volcanoes: from Source to Surface Site Waikolao, Hawaii 20 - 24 August 2012

AGU Chapman Conference on Hawaiian Volcanoes: From Source to Surface Site Waikolao, Hawaii 20 - 24 August 2012 Conveners Michael Poland, USGS – Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, USA Paul Okubo, USGS – Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, USA Ken Hon, University of Hawai'i at Hilo, USA Program Committee Rebecca Carey, University of California, Berkeley, USA Simon Carn, Michigan Technological University, USA Valerie Cayol, Obs. de Physique du Globe de Clermont-Ferrand Helge Gonnermann, Rice University, USA Scott Rowland, SOEST, University of Hawai'i at M noa, USA Financial Support 2 AGU Chapman Conference on Hawaiian Volcanoes: From Source to Surface Site Meeting At A Glance Sunday, 19 August 2012 1600h – 1700h Welcome Reception 1700h – 1800h Introduction and Highlights of Kilauea’s Recent Eruption Activity Monday, 20 August 2012 0830h – 0900h Welcome and Logistics 0900h – 0945h Introduction – Hawaiian Volcano Observatory: Its First 100 Years of Advancing Volcanism 0945h – 1215h Magma Origin and Ascent I 1030h – 1045h Coffee Break 1215h – 1330h Lunch on Your Own 1330h – 1430h Magma Origin and Ascent II 1430h – 1445h Coffee Break 1445h – 1600h Magma Origin and Ascent Breakout Sessions I, II, III, IV, and V 1600h – 1645h Magma Origin and Ascent III 1645h – 1900h Poster Session Tuesday, 21 August 2012 0900h – 1215h Magma Storage and Island Evolution I 1215h – 1330h Lunch on Your Own 1330h – 1445h Magma Storage and Island Evolution II 1445h – 1600h Magma Storage and Island Evolution Breakout Sessions I, II, III, IV, and V 1600h – 1645h Magma Storage -

Chapter 2 the Evolution of Seismic Monitoring Systems at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory

Characteristics of Hawaiian Volcanoes Editors: Michael P. Poland, Taeko Jane Takahashi, and Claire M. Landowski U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1801, 2014 Chapter 2 The Evolution of Seismic Monitoring Systems at the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory By Paul G. Okubo1, Jennifer S. Nakata1, and Robert Y. Koyanagi1 Abstract the Island of Hawai‘i. Over the past century, thousands of sci- entific reports and articles have been published in connection In the century since the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory with Hawaiian volcanism, and an extensive bibliography has (HVO) put its first seismographs into operation at the edge of accumulated, including numerous discussions of the history of Kīlauea Volcano’s summit caldera, seismic monitoring at HVO HVO and its seismic monitoring operations, as well as research (now administered by the U.S. Geological Survey [USGS]) has results. From among these references, we point to Klein and evolved considerably. The HVO seismic network extends across Koyanagi (1980), Apple (1987), Eaton (1996), and Klein and the entire Island of Hawai‘i and is complemented by stations Wright (2000) for details of the early growth of HVO’s seismic installed and operated by monitoring partners in both the USGS network. In particular, the work of Klein and Wright stands and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The out because their compilation uses newspaper accounts and seismic data stream that is available to HVO for its monitoring other reports of the effects of historical earthquakes to extend of volcanic and seismic activity in Hawai‘i, therefore, is built Hawai‘i’s detailed seismic history to nearly a century before from hundreds of data channels from a diverse collection of instrumental monitoring began at HVO. -

The Cavernicolous Fauna of Hawaiian Lava Tubes, 1

Pacific Insects 15 (1): 139-151 20 May 1973 THE CAVERNICOLOUS FAUNA OF HAWAIIAN LAVA TUBES, 1. INTRODUCTION By Francis G. Howarth2 Abstract: The Hawaiian Islands offer great potential for evolutionary research. The discovery of specialized cavernicoles among the adaptively radiating fauna adds to that potential. About 50 lava tubes and a few other types of caves on 4 islands have been investigated. Tree roots, both living and dead, are the main energy source in the caves. Some organic material percolates into the cave through cracks associated with the roots. Cave slimes and accidentals also supply some nutrients. Lava tubes form almost exclusively in pahoehoe basalt, usually by the crusting over of lava rivers. However, the formation can be quite complex. Young basalt has numerous avenues such as vesicles, fissures, layers, and smaller tubes which allow some intercave and interlava flow dispersal of cavernicoles. In older flows these avenues are plugged by siltation or blocked or cut by erosion. The Hawaiian Islands are a string of oceanic volcanic islands stretching more than 2500 km across the mid-Pacific. The western islands are old eroded mountains which are now raised coral reefs and shoals. The eight main eastern islands total 16,667 km2 and are relatively young in geologic age. Ages range from 5+ million years for the island of Kauai to 1 million years for the largest island, Hawaii (Macdonald & Abbott, 1970). The native fauna and flora are composed of those groups which dis persed across upwards of 4000 km of open ocean or island hopped and became successfully established. -

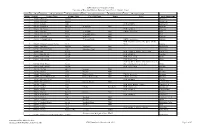

Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names Correction of Diacritical Marks in Hawaiian Names Project - Hawaiʻi Island

Hawaiʻi Board on Geographic Names Correction of Diacritical Marks in Hawaiian Names Project - Hawaiʻi Island Status Key: 1 = Not Hawaiian; 2 = Not Reviewed; 3 = More Research Needed; 4 = HBGN Corrected; 5 = Already Correct in GNIS; 6 = Name Change Status Feat ID Feature Name Feature Class Corrected Name Source Notes USGS Quad Name 1 365008 1940 Cone Summit Mauna Loa 1 365009 1949 Cone Summit Mauna Loa 3 358404 Aa Falls Falls PNH: not listed Kukuihaele 5 358406 ʻAʻahuwela Summit ‘A‘ahuwela PNH Puaakala 3 358412 Aale Stream Stream PNH: not listed Piihonua 4 358413 Aamakao Civil ‘A‘amakāō PNH HBGN: associative Hawi 4 358414 Aamakao Gulch Valley ‘A‘amakāō Gulch PNH Hawi 5 358415 ʻĀʻāmanu Civil ‘Ā‘āmanu PNH Kukaiau 5 358416 ʻĀʻāmanu Gulch Valley ‘Ā‘āmanu Gulch PNH HBGN: associative Kukaiau PNH: Ahalanui, not listed, Laepao‘o; Oneloa, 3 358430 Ahalanui Laepaoo Oneloa Civil Maui Kapoho 4 358433 Ahinahena Summit ‘Āhinahina PNH Puuanahulu 5 1905282 ʻĀhinahina Point Cape ‘Āhinahina Point PNH Honaunau 3 365044 Ahiu Valley PNH: not listed; HBGN: ‘Āhiu in HD Kau Desert 3 358434 Ahoa Stream Stream PNH: not listed Papaaloa 3 365063 Ahole Heiau Locale PNH: Āhole, Maui Pahala 3 1905283 Ahole Heiau Locale PNH: Āhole, Maui Milolii PNH: not listed; HBGN: Āholehōlua if it is the 3 1905284 ʻĀhole Holua Locale slide, Āholeholua if not the slide Milolii 3 358436 Āhole Stream Stream PNH: Āhole, Maui Papaaloa 4 358438 Ahu Noa Summit Ahumoa PNH Hawi 4 358442 Ahualoa Civil Āhualoa PNH Honokaa 4 358443 Ahualoa Gulch Valley Āhualoa Gulch PNH HBGN: associative Honokaa -

Explore Crater Rim Drive and Chain of Craters Road VISITOR ALERT High Amounts of Dangerous Sulfur Dioxide Gas Are Present at the Volcano”S Summit

National Park Service Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park U.S. Department of the Interior Explore Crater Rim Drive and Chain of Craters Road VISITOR ALERT High amounts of dangerous sulfur dioxide gas are present at the volcano”s summit. Personal Safety When driving along Crater Rim Drive, keep your windows closed when visible. Volcanic gas conditions (visually similar to smog) exist along Chain of Craters Road— keep your windows closed when visible. If the air irritates, smells bad, or you have difficulty breathing, return to your vehicle and leave the area. If open, the Kīlauea Visitor Center is a clean air environment. Please be flexible in your travel plans. Some areas may be closed for your safety. Points of Interest Automated Cell Phone Tour 0 Dial 1-808-217-9285 to learn more about the numbered stops listed below. Kīpukapuaulu Nāmakanipaio For emergencies call Mauna Loa Road (13.5-miles one way) Kīlauea Military Camp Campground 808-985-6170 or 911 11 9 Steam Vents 1 To Kailua- Sulphur Banks 4 Kona Crater Rim Drive Jaggar Kīlauea Overlook Museum and Picnic Area Kïlauea Visitor Center 0 Volcano Village 2 7 Volcano House (Gas and Food) closed for renovations Park Entrance 11 KĪLAUEA CALDERA To Hilo 6 Halema‘uma‘u Kīlauea Iki Crater Crater Overlook Thurston Lava Tube (Nāhuku) 3 Road Closed Pu‘u Pua‘i Due to high amounts of sulphur dioxide gas. Pit Devastation Trail 5 Craters Hilina Pali Road (9 miles / 14.5 km one-way) Pu‘u Huluhulu Cinder Cone Hilina Pali Mauna Ulu Shield Overlook Kulanaokuaiki Mau Loa o Campground Mauna Ulu Pu‘u -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 262 131 UD 024 468 TITLE Hawaiian

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 262 131 UD 024 468 TITLE Hawaiian Studies Curriculum Guide. Grade 3. INSTITUTION Hawaii State Dept. of Education, Honolulu. Office of Instructional Services. PUB DATE Jan 85 NOTE 517p.; For the Curriculum Guides for Grades K-1, 2, and 4, see UD 024 466-467, and ED 255 597. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC21 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cultural Awareness; *Cultural Education; Elementary Education; *Environmental Education; Geography; *Grade 3; *Hawaiian; Hawaiians; Instructional Materials; *Learning Activities; Pacific Americans IDENTIFIERS *Hawaii ABSTRACT This curriculum guide suggests activities and educational experiences within a Hawaiian cultural context for Grade 3 students in Hawaiian schools. First, an introduction discussesthe contents of the guide; the relationship of classroom teacher and the kupuna (Hawaiian-speaking elder); the identification and scheduling of Kupunas; and how to use the guide. The remainder of thetext is divided into two major units. Each is preceded byan overview which outlines the subject areas into which Hawaiian Studies instructionis integrated; the emphases or major lesson topics takenup within each subject area; the learning objectives addressed by the instructional activities; and a key to the unit's appendices, which provide cultural information to supplement the activities. Unit I focuseson the location of Hawaii as one of the many groups of islands in the Pacific Ocean. The learning activities suggestedare intended to teach children about place names, flora and fauna,songs, and historical facts about their community, so that they learnto formulate generalizations about location, adaptation, utilization, and conservation of their Hawaiian environment. Unit II presents activities which immerse children in the study of diverse urban and rural communities in Hawaii. -

Maunaloa/Current/Longterm.Html K!Lauea – the Most Active Volcano on Earth K!Lauea Structure

!"#$%&'()'*$+$,-, !"#$%"& '()*%"+, -*./&0%1(2343(5"6"+7+ 8#9*)"/& :/*;0,& .(/$#$ 0$1%$'.2$ 4'5(6'78' "29$6$:2' ;(#<$%(2" *1$#!#$, ."#$12$ 0$1%$'3($ 3#-,/, =(#<$%,<'>:$?2" 0$1%$'3($'$%&'."#$12$@''''' A "/,2#&'#$;$"'(%#B *1$#!#$,@'''''''''''''''''''''''''''''' A 9(":"/,2#& (%#B .(/$#$ $%&'0$1%$'.2$@'''' A "/,2#&'C'9(":"/,2#& DEEFEEE'G HEEFEEE' B6"'$?(F'$##'4' ;(#<$%(2"'+262' $<:,;2'5%(+'I'$62J' (%#B'D',"'2K:,%<:8 LDMEFEEE'B6"'$?(' ."#$12$F'0N'3($F'0N' .2$'O'*1$#!#$, +262'$<:,;2'"/,2#&' ;(#<$%(2"F'+/,#2' .(/$#$ +$"',%':/2' 9(":A"/,2#&'":$?2 P!/$#$ Q"/ < 1*./(=**> ?@+,>#0%%(+#()0&0/% A",$*#"B$(0&("BCD(EFGH P!/$#$ Q"/'62&2),%2& I3B)*%&(,0/&"+#B1()*/0(&@"#(*#0( %*./,0(9*/(&@0("%@(=0$%(*#(&@0(J+K( 8%B"#$ I ?@*%0(+#(&@0(#*/&@("/0(LEMMDMMM(1/%( *B$("#$(N/*="=B1($0/+O0$(9/*)(A".#"( P0"(Q#*(B*#K0/(,"BB0$(:!@"B" 3%@R I ?@*%0(*#(A".#"(!*"("#$(P"B".0" "/0().,@(1*.#K0/(QSEMIEH(>"R("#$( N/*="=1 $0/+O0$(9/*)(0TNB*%+O0( 0/.N&+*#%(*#(A".#"(!*"("#$(P"B".0"C(( Q"/':/,<R%2""',%'S2:26" T,?'!"#$%&'U;(#1:,(% V/2':+('(#&2":'T,?'!"#$%&' ;(#<$%(2"'$62'.(/$#$ 5.(8'$%&' $'"1WS$6,%2';(#<$%('<$##2&' 0!/1R(%$ 508 T(:/'+262'96(W$W#B'962"2%:' 4EEFEEE'B6"'$?( 0!/1R(%$ G :/2'S,"",%?'*$+$,,$%';(#<$%( U"/,+"(0&("BCD(EFFM -B"K.0 "#$(A**/0D(EFFE IM4'G 4EE'R$':/(#2,,:,< $%&'$#R$#,< W$"$#:" QW(6:2&'X962A"/,2#&Y'(6'W16,2&':6$%",:,(%$#'9(":"/,2#&Z T,?'!"#$%&'U;(#1:,(% TB'MEEFEEE'B2$6"'$?( A!@.>*#" 6"%(0T&+#,&(QVR( P*@"B"D(A".#"(P0"D("#$(5."B!B"+ 60/0(",&+O0(%@+0B$% P*@"B" @"$(.#$0/K*#0("()";*/(B"#$%B+$0 :/*="=B1(A".#"(!*"(6"%("B%*(",&+O0("&(&@+%(&+)0 T,?'!"#$%&'U;(#1:,(% TB'DEEFEEE'B2$6"'$?( -

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project by Gary T. Kubota Copyright © 2018, Stories of Change – Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project The Kokua Hawaii Oral History interviews are the property of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project, and are published with the permission of the interviewees for scholarly and educational purposes as determined by Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. This material shall not be used for commercial purposes without the express written consent of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. With brief quotations and proper attribution, and other uses as permitted under U.S. copyright law are allowed. Otherwise, all rights are reserved. For permission to reproduce any content, please contact Gary T. Kubota at [email protected] or Lawrence Kamakawiwoole at [email protected]. Cover photo: The cover photograph was taken by Ed Greevy at the Hawaii State Capitol in 1971. ISBN 978-0-9799467-2-1 Table of Contents Foreword by Larry Kamakawiwoole ................................... 3 George Cooper. 5 Gov. John Waihee. 9 Edwina Moanikeala Akaka ......................................... 18 Raymond Catania ................................................ 29 Lori Treschuk. 46 Mary Whang Choy ............................................... 52 Clyde Maurice Kalani Ohelo ........................................ 67 Wallace Fukunaga .............................................. -

There Is an Aspect of Graffiti That Is Reverse Colonization. I Look at It As the People’S Media.” - Estria

Manifest “There is an aspect of graffiti that is reverse colonization. I look at it as the people’s media.” - Estria Overview Career Timeline Estria has been spray painting for over 26 years, and is recognized around the world as a 1984 graffiti living legend, valued historian, and leader on graffiti’s social and political im- Began spray painting pact. Hailing from San Francisco’s “Golden Age” of graffiti in the 80’s, Estria is a pioneer in painting techniques, and the originator of the stencil tip. Through graffiti Estria has 1993 become an educator, entrepreneur, and social activist, working with numerous non-prof- Began writing articles, teaching its, and high profile corporations. In 2007, Estria founded the “Estria Invitational Graffiti classes, & lecturing at universities on graffiti’s social & political impact. Battle”, a nationwide urban art competition that honors and advances creativity in the Hip Hop arts. Originally from Hawaii, Estria has called the Bay Area home for half of his 1994 life. His murals are known to be whimsical, cultural, political, and vibrant, with a focus Arrested for graffiti, appearing on and dedication to uplift the communities they serve. CNN, National Enquirer, San Fran- cisco Chronicle and, San Francisco Past & Present Clients Cities Painted In Examiner. Sega Italy 2000 MTV Mexico Co-founded “Visual Element”, the Toyota Japan EastSide Arts Alliance’s free mural McKesson Corporation Honduras workshop Visual Element develops Nokia Honolulu youth into the voice of the people. The Mills Corporation San Francisco Though no longer a part of the pro- McDonald’s New York gram, Visual Element continues to Oakland Museum Los Angeles serve at-risk youth. -

View List of the Then Polynesian Collection at the Phoenix Library

Polynesian Cultural Materials donated by Arizona Aloha Festival to the Phoenix Library System Author Call # Title Finding Paradise Don R. Severson 745.0996 The O’ahu Snorkelers and Shore Divers Guide Francis De Carvalho 797.2300 Mark Twain’s Letters from Hawaii Mark Twain 919.6903 My Samoan Chief Fay G. Calkins 919.6130 Saturday Night at the Pahala Theatre Lois-Ann Yamanaka 811.5400 Nā Mo’olelo Hawai’io ka Wā Kahiko (Stories of Old Hawaii) Roy Kākulu Alameida 398.20996 The Craft of Hawaiian Lauhala Weaving Josephine Bird 746.4100 Plants and Flowers of Hawai’i S. H. Sohmer and R. Gustafson 581.9969 Buying Mittens Nankichi Niimi E Samoan Art & Artists Sean Mallon 745.0996 Loyal to the Land Dr. Billy Bergin 636.0109 (The Legendary Parker Ranch, 750-1950) From a Native Daughter Haunani-Kay Trask 320.9969 Kamehameha Susan Morrison 813.6000 (The Warrior King of Hawai’i) Māmaka Kaiao (Hard Cover) Kōmike Hua’ōlelo 499.42321 A modern Hawaiian vocabulary M31 Māmaka Kaiao (Paper back) Kōmike Hua’ōlelo 499.42321 A modern Hawaiian vocabulary M31 Nā pua ali’i O Kaua’i (Ruling Chiefs of Kaua’i) Frederick B. Wichman 996.9020 Melal A Novel of the Pacific Robert Barclay 813.6000 Hawaiian Flower Lei Making Adren J. Bird 745.9230 Ethnic Foods of Hawai’i Ann Kondo Corum 641.5996 Kahana How the Land was Lost Robert H. Stauffer 333.3196 Rarotonga & the Cook Islands Errol Hunt/Nancy Keller 910.0000 Tsunami! Walter C. Dudley/Min 363.3490 Lee Taking Land Tsuyoshi Kotaka 343.5025 (Compulsory Purchase and Regulations in Asian-Pacific David L. -

From the President of Aloha Airlines

scapI.:. to your own spec}al=jSlanll! On the beach, Princeville, Kauai. Put yourself in this picture. Kauai. A place of your own in Paradise. Just moments away from Honolulu-PaJi Ke Kua at Princeville. A home away from home. Or a permanent residence. A plantation atmosphere amid tropic foliage. Pali Ke Kua. What could compare with the joy of spending a weekend-or a week-or forever in such beautiful surroundings. You can right now. PaJi Ke Kua Increment /I is now available. Make your dreams come true. Talk to Mike McCormack Realtors. And put yourself in this picture. mike me carmack. Reallars A Division of The McCormack Land Company, Ltd. Executive offices and Honolulu sales division: Condominium offices: Suite 1212, Davies Pacific Center 4481 Rice Street Lihue, Kauai Phone 245-3991 841 Bishop Street, Honolulu 96801 Phone 537-3311 Princeville, Hanalei Phone 826-6120 Whalers Village, Kaanapali, Maui Phon e 661-3608 1HREAl TOR WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT OF ALOHA AIRLINES Dear Friends, As we approach the end of the year, we look back on 1973 as having MANUFACTURING & DISTRIBUT ION been very si9nifi cant for Aloha Ai rl ines and the people who have Kenneth B. Herndon supported us and worked so hard to brin9 success to our compa ny. Production Manage r David Plummer In 1973, we found ways to bet ter serve you, the inter-island traveler , Mfg . & Distr. Manager wit h new and improved servi ces and additional equipment. Last sprin g, Aloha Airlines added a si xt h Boeing 737 Funb ird to i ts fleet and offered mo re fl ights at more conven ient t imes than ever before. -

<DISC 1> 01.A Kona Hema O Kalani Traditional Vocal

HULA Le’a Presents HAWAIIAN MELE CD-BOX ȊȪǟǝȮǸȮǫƶਙƮƔƛƛƳÁÁ ߅ైದ౽ƝǔƥƶࢩࡑƟƧఝຓƔཌભưƲǒ੫Տ౽ưƲƫƧ¹ ਙࢥ”ºإ ࣞ“ȊȪǟǝȮ½Ȝȧ 1001 ƝǔƧȊȪǟǝȮǸȮǫޯڀƗƶƒບƶƜාƳƒ҃ƐƟ¹ં ƶئףǚƳଵƐǓإ ǚҧౖƲۙǒŗŘ30 Ƴࢌ¹600ےƶҞ ŗŘôŖţŬÁÁ GNCP-1030 Ć31,500á୩ҤâÖĆ30,000áৎಫâ <DISC 1> 01.A Kona Hema O Kalani Traditional Vocal : Kalani Po’omaihealani 02.A Million Moons Over Hawaii Words by Billy Abrams Music by Andy Iona Long Vocal : enry Kaleialoha Allen 03.‘A ‘Oia Words & Music by John Kameaaloha Almeida Vocal : उпdžơLJ 04.A Song of Old Hawaii Words & Music by Johnny Noble & Gordon Beecher Vocal : އÐ้Гᇰ 05.Adios Ke Aloha Words & Music by Prince Leleiohoko Vocal : उпdžơLJ 06.Adventures in Paradise Words & Music by Dorcas Cochran Vocal : Kalani Po’omaihealani 07.Ahi Wela Words & Music by Lizzie Doirin & Lizzie Beckley Vocal : Takako 08.‘Ahulili Words & Music by Scott Ha'i Vocal : dzȢÓdzउҟ 09.Aia I Ka Mau’i Traditional Vocal : Takako 10.Aia I Nu’uanu Ko Lei Nani Traditional Vocal : Aloha Dalire Band 11.Aia La ‘O Pele Traditional, Mae L. Loebenstein Vocal : उпdžơLJ 12.‘Aina O Lanai Words & Music by Val Kepilino Vocal : उпdžơLJ 13.‘Aina O Molokai Words & Music by Kai Davis Vocal : ଇưƕࠃ 14.‘Akaka Falls Words & Music by Helen Perker Vocal : IWAO 15.‘Akaka Falls Words & Music by Helen Lindsey Perker Vocal : Lauloa 16.‘Ala Pikake Words & Music by Manu Boyd Vocal : उпdžơLJ 17.Alekoki Words by Kalalaua, Lunalilo Music by Lizzie Alohikea Vocal : उпdžơLJ 18.‘Alika Words & Music by Charles ka'apa Vocal : Kalani Po’omaihealani 19.Aloha E Kohala Words & Music by Robert Uluwehi Cazimero Vocal : ଇưƕࠃ 20.Aloha E Pele Traditional