Canals in Literature, 1760-1830

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-Under-Lyme Summary List

Listed Buildings in Newcastle-under-Lyme Summary List Listing Historic Site Address Description Grade Date Listed Ref. England List Entry Number Former 644-1/8/15 1291369 28 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Shop premises, possibly originally II 27/09/1972 Newcastle ST5 1RA dwelling, with living Borough accommodation over and at rear (late c18). 644-1/8/16 1196521 36 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 14 Three Tuns II 21/10/1949 ST5 1QL Inn, Red Lion Square. Public house, probably originally dwelling (late c16 partly rebuilt early c19). 644-1/9/55 1196764 Statue Of Queen Victoria Queens Gardens Formerly listed as: Station Walks, II 27/09/1972 Ironmarket Newcastle Staffordshire Victoria Statue. Statue of Queen Victoria (1913). 644-1/10/47 1297487 The Orme Centre Higherland Staffordshire Formerly listed as: Pool Dam, Old II 27/09/1972 ST5 2TE Orme Boy's Primary School. School (1850). 644-1/10/17 1219615 51 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly listed as: 51 High Street, II 27/09/1972 1PN Rainbow Inn. Shop (early c19 but incorporating remains of c17 structure). 644-1/10/18 1297606 56A High Street Newcastle Staffordshire ST5 Formerly known as: 44 High Street. II 21/10/1949 1QL Shop premises, possibly originally build as dwelling (mid-late c18). 644-1/10/19 1291384 75-77 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Formerly known as: 2 Fenton II 27/09/1972 ST5 1PN House, Penkhull street. Bank and offices, originally dwellings (late c18 but extensively modified early c20 with insertion of a new ground floor). 644-1/10/20 1196522 85 High Street Newcastle Staffordshire Commercial premises (c1790). -

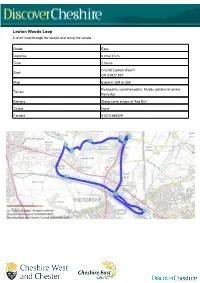

Lawton Woods Loop a Short Loop Through the Woods and Along the Canals

Lawton Woods Loop A short loop through the woods and along the canals. Grade Easy Distance 6 kms/3.5 m Time 2 hours Church Lawton church Start GR SJ822 557 Map Explorer 258 or 268 Field paths, canal towpaths. Muddy patches in winter. Terrain Fairly flat. Barriers Steep canal bridge at Red Bull. Toilets None Contact 01270 686029 Route Details The name Lawton originates in the Lawton family with its family crest being the head of a bleeding wolf. Local legend talks about a man saving the Earl of Chester from being killed by a wolf. This act of bravery took place in about 1200, and to repay the deed, this man was given an area of land between Congleton and Sandbach. The one thousand acre estate became the Parish of Lauton, (later Church Lawton), and is recorded in the Domesday Survey of 1086. The family crest can be found in the church. Lawton Hall, the country seat, of the Lawton family was built in the 17th century, but was almost destroyed by a fire in 1997. During the First World War the hall was used as a hospital, until this time it was still the Lawton family seat. Later it became Lawton Hall school which closed in 1986. Today it has been renovated into private dwellings. Iron smelting took place in the woods during the late 1600’s early 1700’s. Coal mining took place in nearby Kidsgrove and some of the mines extended into the Church Lawton / Red Bull area. The Trent and Mersey canal is linked to the Macclesfield canal at the Harding’s Wood Junction. -

The Harecastle Tunnel the Harecastle Tunnel

© www.talke.info 2008 The Harecastle tunnel Most of this section is quoted from Appelby’s Canal tunnels in England and Wales and Philip Leese’s Kidsgrove times on which I could not possibly improve. Talke’s place as centre of transport with as many as twenty teams of mule drivers stopping at the inns was not to last. The first blow was the opening of the Harecastle tunnel, a remarkable feat of engineering by Thomas Telford and James Brindley. Brindley’s first t tunnel was opened in 1777, five years after the engineer’s death. It is 2,897 feet long, 8feet 6inches wide, and in use until 1918. The second ‘Telford’ tunnel, opened in 1827 and is still in use today, it is 2,929 yards long and much wider. The canals orange colour can be attributed to local geology (iron ore) and the canals clay lining , (a technique called puddling) used to stop the water leaking out , rather than any pollution. James Brindley started work on Harecastle One on 27 June 1766, partly at the urging of local potter Josiah Wedgewood, who needed a safe and cheap means to transport coal to the kilns. ‘In the event, the tunnel took eleven years to build, during which time Brindley died and was replaced as chief engineer by his brother in law, Hugh Henshall. Harecastle had presented all manner of problems, including quicksand, hard rock outcrops, springs and even deadly methane gas, as well as resident engineers and contractors taking advantage of the lack of close supervision by the over- stretched Brindley.’ The tunnel itself was very narrow, much like the mining tunnels at Worsley,and during construction side tunnels were dug to exploit seams of coal (which were also arched and bricked to the same height as the Harecastle I Kidsgrove portal © www.talke.info 2008 main tunnel).’ One local legend states that there is an underground wharf just within the Kidsgrove entrance to load this coal. -

Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan

Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council October 2020 Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Prepared for: Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council AECOM Classification: NULBC UNCLASSIFIED Kidsgrove Town Investment Plan Table of Contents 1. Foreword ......................................................................................................... 5 2. Executive Summary ......................................................................................... 6 3. Contextual analysis ......................................................................................... 9 Kidsgrove Town Deal Investment Area ............................................................................................................. 10 Kidsgrove’s assets and strengths .................................................................................................................... 11 Challenges facing the town ............................................................................................................................. 15 Key opportunities for the town ......................................................................................................................... 19 4. Strategy ......................................................................................................... 24 Vision ............................................................................................................................................................ -

James Brindley ( 1716 - 1772 )

1 James Brindley ( 1716 - 1772 ) These notes are designed to help you with homework and other pro- jects. It will help you to find out: About James Brindley’s early life How he became a famous canal engineer His ideas and inventions. My mum taught me at home. I became the greatest canal engineer of my day! You can see this statue canalrivertrust.org.uk/explorers of James Brindley at Coventry Basin 2 Mr Fixit The spokes should James Brindley was born 300 years ago point inwards, not near Buxton, in Derbyshire. As a boy he outwards, you banana! loved building toy mills and trying them out in the wind and water. Later, James was apprenticed to a master mill- and Oops! wheelwright. It didn’t start off well. He built a cartwheel with spokes facing outwards instead of inwards! Gradually, James became known as someone who could fix any machinery. When his master died he moved to Leek in Staffordshire, to start a new business there. canalrivertrust.org.uk/explorers 3 The Bridgewater Canal The Bridgwater Canal was first called James’s business grew. He worked the Duke’s Canal on all kinds of machinery driven by water, wind and steam. The Duke of Worsley Bridgewater, who owned coal mines RUNCORN Barton coal fields near Manchester, heard about him. Aqueduct ell Irw R er Coal was used i iv ve y R to heat everything r M erse R R Mersey i from houses to v T he e Duk r e’s Manchester furnaces - so Can W al e everyone wanted a v cheap coal. -

The Trent & Mersey Canal Conservation Area Review

The Trent & Mersey Canal Conservation Area Review March 2011 stoke.gov.uk CONTENTS 1. The Purpose of the Conservation Area 1 2. Appraisal Approach 1 3. Consultation 1 4. References 2 5. Legislative & Planning Context 3 6. The Study Area 5 7. Historic Significant & Patronage 6 8. Chatterley Valley Character Area 8 9. Westport Lake Character Area 19 10. Longport Wharf & Middleport Character Area 28 11. Festival Park Character Area 49 12. Etruria Junction Character Area 59 13. A500 (North) Character Area 71 14. Stoke Wharf Character Area 78 15. A500 (South) Character Area 87 16. Sideway Character Area 97 17. Trentham Character Area 101 APPENDICES Appendix A: Maps 1 – 19 to show revisions to the conservation area boundary Appendix B: Historic Maps LIST OF FIGURES Fig. 1: Interior of the Harecastle Tunnels, as viewed from the southern entrance Fig. 2: View on approach to the Harecastle Tunnels Fig. 3: Cast iron mile post Fig. 4: Double casement windows to small building at Harecastle Tunnels, with Staffordshire blue clay paviours in the foreground Fig. 5: Header bond and stone copers to brickwork in Bridge 130, with traditionally designed stone setts and metal railings Fig. 6: Slag walling adjacent to the Ravensdale Playing Pitch Fig. 7: Interplay of light and shadow formed by iron lattice work Fig. 8: Bespoke industrial architecture adds visual interest and activity Fig. 9: View of Westport Lake from the Visitor Centre Fig. 10: Repeated gable and roof pitch details facing towards the canal, south of Westport Lake Road Fig. 11: Industrial building with painted window frames with segmental arches Fig. -

Canal Restrictions by Boat Size

Aire & Calder Navigation The main line is 34.0 miles (54.4 km) long and has 11 locks. The Wakefield Branch is 7.5 miles (12 km) long and has 4 locks. The navigable river Aire to Haddlesey is 6.5 miles (10.4 km) long and has 2 locks. The maximum boat size that can navigate the full main line is length: 200' 2" (61.0 metres) - Castleford Lock beam: 18' 1" (5.5 metres) - Leeds Lock height: 11' 10" (3.6 metres) - Heck Road Bridge draught: 8' 9" (2.68 metres) - cill of Leeds Lock The maximum boat size that can navigate the Wakefield Branch is length: 141' 0" (42.9 metres) beam: 18' 3" (5.55 metres) - Broadreach Lock height: 11' 10" (3.6 metres) draught: 8' 10" (2.7 metres) - cill of Broadreach Lock Ashby Canal The maximum size of boat that can navigate the Ashby Canal is length: There are no locks to limit length beam: 8' 2" (2.49 metres) - Safety Gate near Marston Junction height: 8' 8" (2.64 metres) - Bridge 15a draught: 4' 7" (1.39 metres) Ashton Canal The maximum boat length that can navigate the Ashton Canal is length: 74' 0" (22.5 metres) - Lock 2 beam: 7' 3" (2.2 metres) - Lock 4 height: 6' 5" (1.95 metres) - Bridge 21 (Lumb Lane) draught: 3' 7" (1.1 metres) - cill of Lock 9 Avon Navigation The maximum size of boat that navigate throughout the Avon Navigation is length: 70' (21.3 metres) beam: 12' 6" (3.8 metres) height: 10' (3.0 metres) draught: 4' 0" (1.2 metres) - reduces to 3' 0" or less towards Alveston Weir Basingstoke Canal The maximum size of boat that can navigate the Basingstoke Canal is length: 72' (21.9 metres) beam: 13' -

Staffordshire Pottery and Its History

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Toronto http://archive.org/details/staffordshirepotOOwedg STAFFORDSHIRE POTTERY AND ITS HISTORY STAFFORDSHIRE POTTERY AND ITS HISTORY By JOSIAH C. WEDGWOOD, M.P., C.C. Hon. Sec. of the William Salt Archaeological Society. LONDON SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & CO. LTD. kon Si 710620 DEDICATED TO MY CONSTITUENTS, WHO DO THE WORK CONTENTS Chapter I. The Creation of the Potteries. II. A Peasant Industry. III. Elersand Art. IV. The Salt Glaze Potters. V. The Beginning of the Factory. VI. Wedgwood and Cream Colour. VII. The End of the Eighteenth Century. VIII. Spode and Blue Printing. IX. Methodism and the Capitalists. X. Steam Power and Strikes. XI. Minton Tiles and China. XII. Modern Men and Methods. vy PREFACE THIS account of the potting industry in North Staffordshire will be of interest chiefly to the people of North Stafford- shire. They and their fathers before them have grown up with, lived with, made and developed the English pottery trade. The pot-bank and the shard ruck are, to them, as familiar, and as full of old associations, as the cowshed to the countryman or the nets along the links to the fishing popula- tion. To them any history of the development of their industry will be welcome. But potting is such a specialized industry, so confined to and associated with North Stafford- shire, that it is possible to study very clearly in the case of this industry the cause of its localization, and its gradual change from a home to a factory business. -

THE FOLK-LORE of NORTH STAFFORDSHIRE an Annotated Bibliography

THE FOLK-LORE OF NORTH STAFFORDSHIRE An annotated bibliography 2021 Version 1.6 1 LIST OF ADDITIONS: Additions from version 1.5 : AULT | BUCKLAND (expanded entry) | CLOWES | HARPER | PENMAN | SLEIGH Additions from version 1.4: DAVIS | HOLT | MAYER | MOSS Additions from version 1.3: BLAGG | BUCKLAND | CARRINGTON | HADEN | KEY Additions from version 1.2: BLAKE | BURNE (1896, iii) | BURNE (1914, expanded) | DAY | ELLIOT (1988) | HELM | HOWITT, M. (1845, 1859) | KASKE | MACHIN | SHIRLEY | THOMAS | WARDLE | WELLS | WRIGHT Additions from version 1.1: BERESFORD | DEACON 2 ANON. Legends of the moorlands and forest in north Staffordshire, Hamilton, Adams, and Co., c. 1860. [Local tales retold as reciting verse in the style of the time, with “A Legend of Lud Church” in prose. Has: The Chieftain; Caster’s Bridge; The Heritage; Lud Church; and A Legend of Lud’s Church. Printed locally in Leek by Hall and Son, but issued under the imprint of Hamilton, Adams, and Co. of London. Staffordshire Poets (1928) named the author as a ‘Miss Dakeyne’ and was unable to discover the author’s first name, but noted “Her family were silk manufacturers, of Gradbach Mill” and a Country Life article on the district later added that the family had been so since 1780.] ANON. “Suggested Folk Museum for Staffordshire”, Museums Journal 29, 1930, page 288. ALFORD, V. “Correspondence”, Folk-lore journal, 1953, pages 364-365. [Detailed note on the Abbots Bromley horn dance, from someone who saw it performed three times.] AULT, R. “How the Boggart came to haunt Kidsgrove”, The Sentinel newspaper, 30th October 2020, online. [The Kidsgrove Boggart. -

Full Response

Working Draft Environmental Statement [WDES] consultation for HS2 Phase 2b Full response Section LA11- Staveley to Aston Consultation published October 2018 Close - 21st December 2018 Lessons from history The Canal Today The winters of 1767 and 1768 were some of the wettest on record. Despite turnpike roads, trade was disrupted for 1.1 The Chesterfield Canal Trust [hereafter referred to as ‘the Trust’] exists to promote the Chesterfield Canal as months, and even London flooded. a waterway for all users - whether on foot, cycle or boat, and to campaign for the canal’s restoration. The Trust is a registered charity and Company Limited by Guarantee, having 1,800 members [October 2018]. It was originally founded Seth Ellis Stevenson, Rector and Headmaster of Retford Grammar School, saw first hand the detrimental impact on as the Chesterfield Canal Society in 1976. CCT is a partner organisation in the Chesterfield Canal Partnership and trade in the North of Derbyshire, South Yorkshire and North Nottinghamshire. He resolved to build an alliance of together with local authorities, the Canal and River Trust, Inland Waterways Association, wildlife and environmental tradespeople and merchants to explore the creation of a canal from Chesterfield to the River Trent. He had seen the bodies is committed to fully restoring the Chesterfield Canal. So far 37 of the 46 miles of the canal have been work of James Brindley and the Worsley Canal built by him for the Duke of Bridgewater and invited Brindley to talk to brought back into use and there remain just 9 miles left to restore. Full restoration will make it possible to travel from interested parties about the development of a waterway to meet their need for reliable, high capacity transportation Chesterfield in North Derbyshire to West Stockwith in North Nottinghamshire on the River Trent once more. -

Ideals the English Narrow Canals the Seven Wonders of the Waterways

1 Ideals The English Narrow Canals The Seven Wonders of the Waterways 2 The Ideals - english narrow Canals - then... and now? When planning the canal in 1795/96 Austria had no experience with navigable canals. In those times the industrial ideal was England. Although the technique of building canals had been developed before on the main land England built economic canals used for the so called „Narrowboats“. The planner of the Austrian canal Sebastian von Maillard travelled with a group of experts to the English and Scottish existing canals and the canals in progress and visited horsecars and the recently in Cardiff opened first steam railway. The following virtual journey leaves from London on the Thames to canals that already existed in 1795/1796 and ends at the Bridgewater Canal in the former coal-mining area and stronghold of der cotton mills around Manchester. The Bridgewater Canalwas opened in 1761 and is known as first navigable waterway of the then modern narrow canals in England. When S. v. Maillard travelled Great Britain at the end of the 18th century there were already about 40 narrow canals operating. In the heyday of the navigable canals in the 19th century there were over 100 navigable canals for freight. Nowadays the onlinelexicon wasserwege.eu knows about 70 touristy used canals in Great Britain. The waterway via ship from London up to the Bridgewater Canal (Manchester) that might have been visited by Maillard has been navigable at its time like this: Thames River Oxford Canal Coventry Canal Trent & Mersey Canal Bridgewater Canal The canals were „children“ of the industrialisation. -

Artist Brief: Appetite & CRT in Kidsgrove Appetite & Canal & River

Artist Brief: Appetite & CRT in Kidsgrove Figure 1: Image taken from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harecastle_Tunnel Appetite & Canal & River Trust are looking to collaborate with an artist(s) on a project for Kidsgrove. In the first year of our partnership and the development of Appetite’s work in Kidsgrove as part of the Arts Council England Creative People and Places programme, we are working with artists around three areas of work that connect the people, town centre, and its connectivity to the canal of Kidsgrove. The two other themes for our work are Light and Young People and Families. This brief is for artist(s) to work on theme of Environment. Appetite works with other partners in the Kidsgrove area: a key partner and consortium member is GoKidsgrove (a town centre partnership for the town) amongst others including Newcastle Borough Council and We Are Aspire Group. For this project, we would like to focus on the environment as the theme and areas we’re interested in are: - The climate emergency and single use plastics in and around the canalside; - The welcome the environment provides to those that connect to the train station, canal, town side and streets of the residential areas of Kidsgrove; - The future regeneration of Kidsgrove and the improvements to the canal and town centre areas; - Use and re-use of the spaces and places adjoining and connecting the canalside; - Biodiversity and the connection of green (land) and blue (water) spaces for wildlife and communities. The project could be a research residency or a pilot project. Through all of our projects we want to build connections with the people and place of Kidsgrove through building relationships with a wide variety of residents, business owners, volunteers and partners in the area to involve them in future decision-making for arts and cultural projects for the area supported by Appetite.