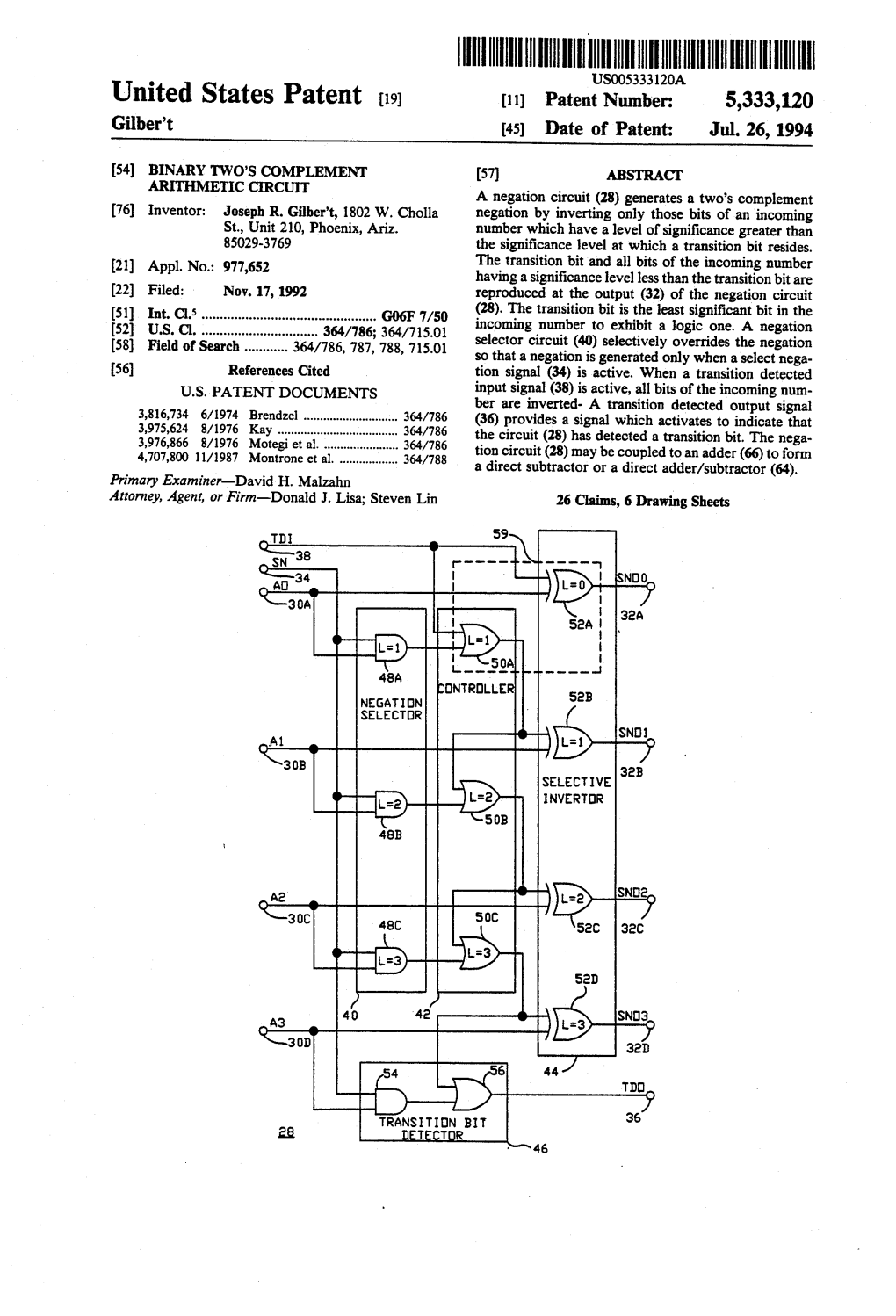

IIIHIIIHIIII US005333120A United States Patent (19) (11) Patent Number: 5,333,120 Gilbert 45) Date of Patent: Jul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Data Representation

Chapter 4 – Data Representation The focus of this chapter is the representation of data in a digital computer. We begin with a review of several number systems (decimal, binary, octal, and hexadecimal) and a discussion of methods for conversion between the systems. The two most important methods are conversion from decimal to binary and binary to decimal. The conversions between binary and each of octal and hexadecimal are quite simple. Other conversions, such as hexadecimal to decimal, are often best done via binary. After discussion of conversion between bases, we discuss the methods used to store integers in a digital computer: one’s complement and two’s complement arithmetic. This includes a characterization of the range of integers that can be stored given the number of bits allocated to store an integer. The most common integer storage formats are 16, 32, and 64 bits. The next topic for this chapter is the storage of real (floating point) numbers. This discussion will mention the standard put forward by the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, the IEEE Standard 754 for floating point numbers, but will focus on the base–16 format used by IBM Mainframes. The chapter closes with a discussion of codes for storing characters, focusing on the EBCDIC system used on IBM mainframes. Number Systems There are four number systems of possible interest to the computer programmer: decimal, binary, octal, and hexadecimal. Each system is characterized by its base or radix, always given in decimal, and the set of permissible digits. Note that the hexadecimal numbering system calls for more than ten digits, so we use the first six letters of the alphabet. -

Bits and Bytes and Words, Oh My!

Bits and Bytes and Words, Oh My! Let’s get down to the real ni8y gri8y • CIS 211 In principle you already know ... Computer memory is binary (base 2) Everything: instrucEons, numbers, strings, ... memory is just one big array of binary numbers If I ask you what 01101011101010 represents, the only correct answer is “it depends” 0 = False = 0 volts; 1 = True = 5 volts (maybe) • CIS 211 CPU and Memory Main Memory CPU Address ALU Reg Reg Reg Values Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Other buses • CIS 211 CPU and Memory (simplified*) Main Memory CPU Address ALU Reg Reg Reg Values Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Other buses • CIS 211 (*with several useful lies) CPU and Memory CPU places a memory address on the address bus CPU may place a value on the data base and assert a “write” line (wire) or assert a “read” line and read a value from the data bus Main Memory CPU Address ALU Reg Reg Reg Values Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Other buses • CIS 211 A few terms: • A bit is a single binary digit • A byte is 8 binary digits • Most computer memory is “byte addressed”; a byte is the smallest addressable unit • What’s half a byte? (4 bits)? • A “word” is a sequence of bytes • Usually 4 bytes (32 bits) or 8 bytes (64 bits) depending on the computer (see next slide) 1 = True = 5 volts ; 0 = False = 0 volts (or 3.3 volts) • CIS 211 Typical byte-addressed memory 15 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 with 32-bit words 14 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 13 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 12 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 11 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 8 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 -

Endian: from the Ground up a Coordinated Approach

WHITEPAPER Endian: From the Ground Up A Coordinated Approach By Kevin Johnston Senior Staff Engineer, Verilab July 2008 © 2008 Verilab, Inc. 7320 N MOPAC Expressway | Suite 203 | Austin, TX 78731-2309 | 512.372.8367 | www.verilab.com WHITEPAPER INTRODUCTION WHat DOES ENDIAN MEAN? Data in Imagine XYZ Corp finally receives first silicon for the main Endian relates the significance order of symbols to the computers chip for its new camera phone. All initial testing proceeds position order of symbols in any representation of any flawlessly until they try an image capture. The display is kind of data, if significance is position-dependent in that regularly completely garbled. representation. undergoes Of course there are many possible causes, and the debug Let’s take a specific type of data, and a specific form of dozens if not team analyzes code traces, packet traces, memory dumps. representation that possesses position-dependent signifi- There is no problem with the code. There is no problem cance: A digit sequence representing a numeric value, like hundreds of with data transport. The problem is eventually tracked “5896”. Each digit position has significance relative to all down to the data format. other digit positions. transformations The development team ran many, many pre-silicon simula- I’m using the word “digit” in the generalized sense of an between tions of the system to check datapath integrity, bandwidth, arbitrary radix, not necessarily decimal. Decimal and a few producer and error correction. The verification effort checked that all other specific radixes happen to be particularly useful for the data submitted at the camera port eventually emerged illustration simply due to their familiarity, but all of the consumer. -

Binary Numbers 8'S Colum 8'S Colum 2'S Colum 1'S 4'S Colum 4'S N N N N

Codes and number systems Introduction to Computer Yung-Yu Chuang with slides by Nisan & Schocken (www.nand2tetris.org) and Harris & Harris (DDCA) Coding • Assume that you want to communicate with your friend with a flashlight in a night, what will you do? light painting? What’s the problem? Solution #1 • A: 1 blink • B: 2 blibliknks • C: 3 blinks : • Z: 26 blinks Wha t’s the problem ? • How are you? = 131 blinks Solution #2: Morse code Hello Lookup • It is easy to translate into Morse code than reverse. Why? Lookup Lookup Useful for checking the correctness/ redddundency Braille Braille What’s common in these codes? • They are both binary codes. Binary representations • Electronic Implementation – Easy to store with bitblbistable elemen ts – Reliably transmitted on noisy and inaccurate wires 0 1 0 3.3V 2.8V 0.5V 0.0V Number systems <13> 1 Chapter = = Systems 2 1's column 10 1's column 10's column 2's column 100's column 4's column 1000's column 8's column 5374 1101 Number • numbers Decimal • Binary numbers Number Systems • Decimal numbers 1000's col 10's colum 1's column 100's colu u m n mn n 3 2 1 0 537410 = 5 ? 10 + 3 ? 10 + 7 ? 10 + 4 ? 10 five three seven four thousands hundreds tens ones • Binary numbers 8's colum 2's colum 1's colum 4's colum n n n n 3 2 1 0 11012 = 1 ? 2 + 1 ? 2 + 0 ? 2 + 1 ? 2 = 1310 one one no one eight four two one Chapter 1 <14> Binary numbers • Digits are 1 and 0 (a binary dig it is calle d a bit) 1 = true 0 = false • MSB –most significant bit • LSB –least significant bit MSB LSB • Bit numbering: 1 0 1 1 0 -

TCG ACPI Specification

TCG ACPI Specification Family “1.2” and “2.0” Version 1.3 Revision 8 August 5, 2021 PUBLISHED Contact: [email protected] TCG PUBLISHED Copyright © TCG 2021 TCG TCG ACPI Specification Disclaimers, Notices, and License Terms THIS SPECIFICATION IS PROVIDED "AS IS" WITH NO WARRANTIES WHATSOEVER, INCLUDING ANY WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY, NONINFRINGEMENT, FITNESS FOR ANY PARTICULAR PURPOSE, OR ANY WARRANTY OTHERWISE ARISING OUT OF ANY PROPOSAL, SPECIFICATION OR SAMPLE. Without limitation, TCG disclaims all liability, including liability for infringement of any proprietary rights, relating to use of information in this specification and to the implementation of this specification, and TCG disclaims all liability for cost of procurement of substitute goods or services, lost profits, loss of use, loss of data or any incidental, consequential, direct, indirect, or special damages, whether under contract, tort, warranty or otherwise, arising in any way out of use or reliance upon this specification or any information herein. This document is copyrighted by Trusted Computing Group (TCG), and no license, express or implied, is granted herein other than as follows: You may not copy or reproduce the document or distribute it to others without written permission from TCG, except that you may freely do so for the purposes of (a) examining or implementing TCG specifications or (b) developing, testing, or promoting information technology standards and best practices, so long as you distribute the document with these disclaimers, notices, and license terms. Contact the Trusted Computing Group at www.trustedcomputinggroup.org for information on specification licensing through membership agreements. Any marks and brands contained herein are the property of their respective owners. -

Numbering Systems

12 Digital Principles Switching Theory R HAPTE 1 C NUMBERING SYSTEMS 1.0 INTRODUCTION Inside today’s computers, data is represented as 1’s and 0’s. These 1’s and 0’s might be stored magnetically on a disk, or as a state in a transistor, core, or vacuum tube. To perform useful operations on these 1’s and 0’s one have to organize them together into patterns that make up codes. Modern digital systems do not represent numeric values using the decimal system. Instead, they typically use a binary or two’s complement numbering system. To understand the digital system arithmetic, one must understand how digital systems represent numbers. This chapter discusses several important concepts including the binary, octal and hexadeci- mal numbering systems, binary data organization (bits, nibbles, bytes, words, and double words), signed and unsigned numbering systems. If one is already familiar with these terms he should at least skim this material. 1.1 A REVIEW OF THE DECIMAL SYSTEM People have been using the decimal (base 10) numbering system for so long that they probably take it for granted. When one see a number like “123”, he don’t think about the value 123; rather, he generate a mental image of how many items this value represents. In reality, however, the number 123 represents: 1*102 + 2*101 + 3*100 OR 100 + 20 + 3 Each digit appearing to the left of the decimal point represents a value between zero and nine times an increasing power of ten. Digits appearing to the right of the decimal point represent a value between zero and nine times an increasing negative power of ten. -

An Empirical Analysis of the Ipv4 Number Market

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository Buying numbers: An Empirical Analysis of the IPv4 Number Market Milton L. Mueller Brenden Kuerbis Syracuse University Syracuse University [email protected] and University of Toronto [email protected] Abstract The emergence of a trading market for previously allocated Internet number blocks is an important change in Internet governance. Almost all of the Internet’s 32-bit address space has been given out, and we have not migrated to a new internet protocol, IPv6, with a larger address space. IP addresses are therefore being commoditized, as organizations with surplus numbers sell address blocks to organizations that want more. Though controversial, we know little about this phenomenon. This paper quantifies the number of address blocks that have been traded as of July 2012 and analyzes the scant information that exists about the pricing of these resources, discovering the emergence of a billion dollar market. The paper then shows how this factual information relates to key policy debates, in particularly the role of needs assessment and property rights in IPv4 number blocks. Keywords: Internet governance, IP address markets, IPv4 scarcity, IPv6 migration, property rights Introduction One of the most important but least-studied aspects of Internet policy is the emergence of a trading market for previously allocated Internet number blocks. Without unique Internet protocol numbers for the networks and devices attached, the Internet simply doesn’t work. The original Internet Protocol standard, known as IPv4, specified a 32-bit numbering space, which provided slightly less than 4 billion unique numbers that could be used as addresses (Postel, 1981). -

Introduction to Computer Data Representation

Introduction to Computer Data Representation Peter Fenwick The University of Auckland (Retired) New Zealand Bentham Science Publishers Bentham Science Publishers Bentham Science Publishers Executive Suite Y - 2 P.O. Box 446 P.O. Box 294 PO Box 7917, Saif Zone Oak Park, IL 60301-0446 1400 AG Bussum Sharjah, U.A.E. USA THE NETHERLANDS [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Please read this license agreement carefully before using this eBook. Your use of this eBook/chapter constitutes your agreement to the terms and conditions set forth in this License Agreement. This work is protected under copyright by Bentham Science Publishers to grant the user of this eBook/chapter, a non- exclusive, nontransferable license to download and use this eBook/chapter under the following terms and conditions: 1. This eBook/chapter may be downloaded and used by one user on one computer. The user may make one back-up copy of this publication to avoid losing it. The user may not give copies of this publication to others, or make it available for others to copy or download. For a multi-user license contact [email protected] 2. All rights reserved: All content in this publication is copyrighted and Bentham Science Publishers own the copyright. You may not copy, reproduce, modify, remove, delete, augment, add to, publish, transmit, sell, resell, create derivative works from, or in any way exploit any of this publication’s content, in any form by any means, in whole or in part, without the prior written permission from Bentham Science Publishers. 3. The user may print one or more copies/pages of this eBook/chapter for their personal use. -

Data Representation

Data Representation Data Representation Chapter Three A major stumbling block many beginners encounter when attempting to learn assembly language is the common use of the binary and hexadecimal numbering systems. Many programmers think that hexadecimal (or hex1) numbers represent absolute proof that God never intended anyone to work in assembly language. While it is true that hexadecimal numbers are a little different from what you may be used to, their advan- tages outweigh their disadvantages by a large margin. Nevertheless, understanding these numbering systems is important because their use simplifies other complex topics including boolean algebra and logic design, signed numeric representation, character codes, and packed data. 3.1 Chapter Overview This chapter discusses several important concepts including the binary and hexadecimal numbering sys- tems, binary data organization (bits, nibbles, bytes, words, and double words), signed and unsigned number- ing systems, arithmetic, logical, shift, and rotate operations on binary values, bit fields and packed data. This is basic material and the remainder of this text depends upon your understanding of these concepts. If you are already familiar with these terms from other courses or study, you should at least skim this material before proceeding to the next chapter. If you are unfamiliar with this material, or only vaguely familiar with it, you should study it carefully before proceeding. All of the material in this chapter is important! Do not skip over any material. In addition to the basic material, this chapter also introduces some new HLA state- ments and HLA Standard Library routines. 3.2 Numbering Systems Most modern computer systems do not represent numeric values using the decimal system. -

Programming the 65816

Programming the 65816 Including the 6502, 65C02 and 65802 Distributed and published under COPYRIGHT LICENSE AND PUBLISHING AGREEMENT with Authors David Eyes and Ron Lichty EFFECTIVE APRIL 28, 1992 Copyright © 2007 by The Western Design Center, Inc. 2166 E. Brown Rd. Mesa, AZ 85213 480-962-4545 (p) 480-835-6442 (f) www.westerndesigncenter.com The Western Design Center Table of Contents 1) Chapter One .......................................................................................................... 12 Basic Assembly Language Programming Concepts..................................................................................12 Binary Numbers.................................................................................................................................................... 12 Grouping Bits into Bytes....................................................................................................................................... 13 Hexadecimal Representation of Binary................................................................................................................ 14 The ACSII Character Set ..................................................................................................................................... 15 Boolean Logic........................................................................................................................................................ 16 Logical And....................................................................................................................................................... -

Sun Studio 10: C User's Guide

C User’s Guide Sun™ Studio 10 Sun Microsystems, Inc. www.sun.com Part No. 819-0494-10 January 2005, Revision A Submit comments about this document at: http://www.sun.com/hwdocs/feedback Copyright © 2005 Sun Microsystems, Inc., 4150 Network Circle, Santa Clara, California 95054, U.S.A. All rights reserved. U.S. Government Rights - Commercial software. Government users are subject to the Sun Microsystems, Inc. standard license agreement and applicable provisions of the FAR and its supplements. Use is subject to license terms. This distribution may include materials developed by third parties. Parts of the product may be derived from Berkeley BSD systems, licensed from the University of California. UNIX is a registered trademark in the U.S. and in other countries, exclusively licensed through X/Open Company, Ltd. Sun, Sun Microsystems, the Sun logo, Java, and JavaHelp are trademarks or registered trademarks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries.All SPARC trademarks are used under license and are trademarks or registered trademarks of SPARC International, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. Products bearing SPARC trademarks are based upon architecture developed by Sun Microsystems, Inc. This product is covered and controlled by U.S. Export Control laws and may be subject to the export or import laws in other countries. Nuclear, missile, chemical biological weapons or nuclear maritime end uses or end users, whether direct or indirect, are strictly prohibited. Export or reexport to countries subject to U.S. embargo or to entities identified on U.S. export exclusion lists, including, but not limited to, the denied persons and specially designated nationals lists is strictly prohibited. -

The P4 Language Specification, V 1.1.0

The P4 Language Specification Version 1.1.0 January 27, 2016 The P4 Language Consortium © 2014-2016, The P4 Language Consortium CONTENTS CONTENTS Contents 1 Introduction5 1.1 The P4 Abstract Model...............................5 1.2 The mTag Example.................................7 1.3 Specification Conventions.............................7 2 Structure of the P4 Language8 2.1 Abstractions.....................................8 2.2 Value Specifications................................9 2.3 Types and declarations............................... 11 2.4 P4 data types..................................... 12 2.4.1 Principles.................................. 12 2.4.2 Base types.................................. 13 2.4.3 Portability.................................. 13 2.4.4 No saturated types............................. 14 2.4.5 Boolean................................... 14 2.4.6 Unsigned integers (bit-strings)...................... 14 2.4.7 Signed Integers............................... 15 2.4.8 Dynamically-sized bit-strings....................... 15 2.4.9 Infinite-precision integers......................... 16 2.4.10 Integer literal types............................. 16 2.5 Base type operations................................ 17 2.5.1 Computations on Boolean values.................... 17 2.5.2 Operations on unsigned fixed-width integers............. 18 2.5.3 Operations on signed fixed-width integers............... 18 2.5.4 A note about shifts............................. 19 2.5.5 varbit operations............................. 21 2.5.6 Operations