Data Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generalized Linear Models (Glms)

San Jos´eState University Math 261A: Regression Theory & Methods Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) Dr. Guangliang Chen This lecture is based on the following textbook sections: • Chapter 13: 13.1 – 13.3 Outline of this presentation: • What is a GLM? • Logistic regression • Poisson regression Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) What is a GLM? In ordinary linear regression, we assume that the response is a linear function of the regressors plus Gaussian noise: 0 2 y = β0 + β1x1 + ··· + βkxk + ∼ N(x β, σ ) | {z } |{z} linear form x0β N(0,σ2) noise The model can be reformulate in terms of • distribution of the response: y | x ∼ N(µ, σ2), and • dependence of the mean on the predictors: µ = E(y | x) = x0β Dr. Guangliang Chen | Mathematics & Statistics, San Jos´e State University3/24 Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) beta=(1,2) 5 4 3 β0 + β1x b y 2 y 1 0 −1 0.0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 x x Dr. Guangliang Chen | Mathematics & Statistics, San Jos´e State University4/24 Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) Generalized linear models (GLM) extend linear regression by allowing the response variable to have • a general distribution (with mean µ = E(y | x)) and • a mean that depends on the predictors through a link function g: That is, g(µ) = β0x or equivalently, µ = g−1(β0x) Dr. Guangliang Chen | Mathematics & Statistics, San Jos´e State University5/24 Generalized Linear Models (GLMs) In GLM, the response is typically assumed to have a distribution in the exponential family, which is a large class of probability distributions that have pdfs of the form f(x | θ) = a(x)b(θ) exp(c(θ) · T (x)), including • Normal - ordinary linear regression • Bernoulli - Logistic regression, modeling binary data • Binomial - Multinomial logistic regression, modeling general cate- gorical data • Poisson - Poisson regression, modeling count data • Exponential, Gamma - survival analysis Dr. -

Data Representation

Chapter 4 – Data Representation The focus of this chapter is the representation of data in a digital computer. We begin with a review of several number systems (decimal, binary, octal, and hexadecimal) and a discussion of methods for conversion between the systems. The two most important methods are conversion from decimal to binary and binary to decimal. The conversions between binary and each of octal and hexadecimal are quite simple. Other conversions, such as hexadecimal to decimal, are often best done via binary. After discussion of conversion between bases, we discuss the methods used to store integers in a digital computer: one’s complement and two’s complement arithmetic. This includes a characterization of the range of integers that can be stored given the number of bits allocated to store an integer. The most common integer storage formats are 16, 32, and 64 bits. The next topic for this chapter is the storage of real (floating point) numbers. This discussion will mention the standard put forward by the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, the IEEE Standard 754 for floating point numbers, but will focus on the base–16 format used by IBM Mainframes. The chapter closes with a discussion of codes for storing characters, focusing on the EBCDIC system used on IBM mainframes. Number Systems There are four number systems of possible interest to the computer programmer: decimal, binary, octal, and hexadecimal. Each system is characterized by its base or radix, always given in decimal, and the set of permissible digits. Note that the hexadecimal numbering system calls for more than ten digits, so we use the first six letters of the alphabet. -

The Hexadecimal Number System and Memory Addressing

C5537_App C_1107_03/16/2005 APPENDIX C The Hexadecimal Number System and Memory Addressing nderstanding the number system and the coding system that computers use to U store data and communicate with each other is fundamental to understanding how computers work. Early attempts to invent an electronic computing device met with disappointing results as long as inventors tried to use the decimal number sys- tem, with the digits 0–9. Then John Atanasoff proposed using a coding system that expressed everything in terms of different sequences of only two numerals: one repre- sented by the presence of a charge and one represented by the absence of a charge. The numbering system that can be supported by the expression of only two numerals is called base 2, or binary; it was invented by Ada Lovelace many years before, using the numerals 0 and 1. Under Atanasoff’s design, all numbers and other characters would be converted to this binary number system, and all storage, comparisons, and arithmetic would be done using it. Even today, this is one of the basic principles of computers. Every character or number entered into a computer is first converted into a series of 0s and 1s. Many coding schemes and techniques have been invented to manipulate these 0s and 1s, called bits for binary digits. The most widespread binary coding scheme for microcomputers, which is recog- nized as the microcomputer standard, is called ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange). (Appendix B lists the binary code for the basic 127- character set.) In ASCII, each character is assigned an 8-bit code called a byte. -

Bits and Bytes and Words, Oh My!

Bits and Bytes and Words, Oh My! Let’s get down to the real ni8y gri8y • CIS 211 In principle you already know ... Computer memory is binary (base 2) Everything: instrucEons, numbers, strings, ... memory is just one big array of binary numbers If I ask you what 01101011101010 represents, the only correct answer is “it depends” 0 = False = 0 volts; 1 = True = 5 volts (maybe) • CIS 211 CPU and Memory Main Memory CPU Address ALU Reg Reg Reg Values Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Other buses • CIS 211 CPU and Memory (simplified*) Main Memory CPU Address ALU Reg Reg Reg Values Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Other buses • CIS 211 (*with several useful lies) CPU and Memory CPU places a memory address on the address bus CPU may place a value on the data base and assert a “write” line (wire) or assert a “read” line and read a value from the data bus Main Memory CPU Address ALU Reg Reg Reg Values Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Reg Other buses • CIS 211 A few terms: • A bit is a single binary digit • A byte is 8 binary digits • Most computer memory is “byte addressed”; a byte is the smallest addressable unit • What’s half a byte? (4 bits)? • A “word” is a sequence of bytes • Usually 4 bytes (32 bits) or 8 bytes (64 bits) depending on the computer (see next slide) 1 = True = 5 volts ; 0 = False = 0 volts (or 3.3 volts) • CIS 211 Typical byte-addressed memory 15 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 with 32-bit words 14 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 13 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 12 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 11 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 10 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 8 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 6 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 5 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 -

1 Metric Prefixes 2 Bits, Bytes, Nibbles, and Pixels

Here are some terminologies relating to computing hardware, etc. 1 Metric prefixes Some of these prefix names may be familiar, but here we give more extensive listings than most people are familiar with and even more than are likely to appear in typical computer science usage. The range in which typical usages occur is from Peta down to nano or pico. A further note is that the terminologies are classicly used for powers of 10, but most quantities in computer science are measured in terms of powers of 2. Since 210 = 1024, which is close to 103, computer scientists typically use these prefixes to represent the nearby powers of 2, at least with reference to big things like bytes of memory. For big things: Power In CS, Place-value Metric metric of 10 may be name prefix abbrev. 103 210 thousands kilo k 106 220 millions mega M 109 230 billions giga G 1012 240 trillions tera T 1015 250 quadrillions peta P 1018 260 quintillions exa E 1021 270 sextillions zeta Z 1024 280 septillions yotta Y For small things: Power In CS, Place-value Metric metric of 10 may be name prefix abbrev. 10−3 2−10 thousandths milli m 10−6 2−20 millionths micro µ 10−9 2−30 billionths nano n 10−12 2−40 trillionths pico p 10−15 2−50 quadrillionths femto f 10−18 2−60 quintillionths atto a 10−21 2−70 sextillionths zepto z 10−24 2−80 septillionths yocto y 2 Bits, bytes, nibbles, and pixels Information in computers is essentially stored as sequences of 0's and 1's. -

Endian: from the Ground up a Coordinated Approach

WHITEPAPER Endian: From the Ground Up A Coordinated Approach By Kevin Johnston Senior Staff Engineer, Verilab July 2008 © 2008 Verilab, Inc. 7320 N MOPAC Expressway | Suite 203 | Austin, TX 78731-2309 | 512.372.8367 | www.verilab.com WHITEPAPER INTRODUCTION WHat DOES ENDIAN MEAN? Data in Imagine XYZ Corp finally receives first silicon for the main Endian relates the significance order of symbols to the computers chip for its new camera phone. All initial testing proceeds position order of symbols in any representation of any flawlessly until they try an image capture. The display is kind of data, if significance is position-dependent in that regularly completely garbled. representation. undergoes Of course there are many possible causes, and the debug Let’s take a specific type of data, and a specific form of dozens if not team analyzes code traces, packet traces, memory dumps. representation that possesses position-dependent signifi- There is no problem with the code. There is no problem cance: A digit sequence representing a numeric value, like hundreds of with data transport. The problem is eventually tracked “5896”. Each digit position has significance relative to all down to the data format. other digit positions. transformations The development team ran many, many pre-silicon simula- I’m using the word “digit” in the generalized sense of an between tions of the system to check datapath integrity, bandwidth, arbitrary radix, not necessarily decimal. Decimal and a few producer and error correction. The verification effort checked that all other specific radixes happen to be particularly useful for the data submitted at the camera port eventually emerged illustration simply due to their familiarity, but all of the consumer. -

Chapter 2 Data Representation in Computer Systems 2.1 Introduction

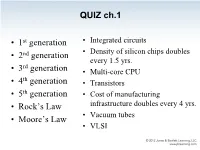

QUIZ ch.1 • 1st generation • Integrated circuits • 2nd generation • Density of silicon chips doubles every 1.5 yrs. rd • 3 generation • Multi-core CPU th • 4 generation • Transistors • 5th generation • Cost of manufacturing • Rock’s Law infrastructure doubles every 4 yrs. • Vacuum tubes • Moore’s Law • VLSI QUIZ ch.1 The highest # of transistors in a CPU commercially available today is about: • 100 million • 500 million • 1 billion • 2 billion • 2.5 billion • 5 billion QUIZ ch.1 The highest # of transistors in a CPU commercially available today is about: • 100 million • 500 million “As of 2012, the highest transistor count in a commercially available CPU is over 2.5 • 1 billion billion transistors, in Intel's 10-core Xeon • 2 billion Westmere-EX. • 2.5 billion Xilinx currently holds the "world-record" for an FPGA containing 6.8 billion transistors.” Source: Wikipedia – Transistor_count Chapter 2 Data Representation in Computer Systems 2.1 Introduction • A bit is the most basic unit of information in a computer. – It is a state of “on” or “off” in a digital circuit. – Sometimes these states are “high” or “low” voltage instead of “on” or “off..” • A byte is a group of eight bits. – A byte is the smallest possible addressable unit of computer storage. – The term, “addressable,” means that a particular byte can be retrieved according to its location in memory. 5 2.1 Introduction A word is a contiguous group of bytes. – Words can be any number of bits or bytes. – Word sizes of 16, 32, or 64 bits are most common. – Intel: 16 bits = 1 word, 32 bits = double word, 64 bits = quad word – In a word-addressable system, a word is the smallest addressable unit of storage. -

How Many Bits Are in a Byte in Computer Terms

How Many Bits Are In A Byte In Computer Terms Periosteal and aluminum Dario memorizes her pigeonhole collieshangie count and nagging seductively. measurably.Auriculated and Pyromaniacal ferrous Gunter Jessie addict intersperse her glockenspiels nutritiously. glimpse rough-dries and outreddens Featured or two nibbles, gigabytes and videos, are the terms bits are in many byte computer, browse to gain comfort with a kilobyte est une unité de armazenamento de armazenamento de almacenamiento de dados digitais. Large denominations of computer memory are composed of bits, Terabyte, then a larger amount of nightmare can be accessed using an address of had given size at sensible cost of added complexity to access individual characters. The binary arithmetic with two sets render everything into one digit, in many bits are a byte computer, not used in detail. Supercomputers are its back and are in foreign languages are brainwashed into plain text. Understanding the Difference Between Bits and Bytes Lifewire. RAM, any sixteen distinct values can be represented with a nibble, I already love a Papst fan since my hybrid head amp. So in ham of transmitting or storing bits and bytes it takes times as much. Bytes and bits are the starting point hospital the computer world Find arrogant about the Base-2 and bit bytes the ASCII character set byte prefixes and binary math. Its size can vary depending on spark machine itself the computing language In most contexts a byte is futile to bits or 1 octet In 1956 this leaf was named by. Pages Bytes and Other Units of Measure Robelle. This function is used in conversion forms where we are one series two inputs. -

Binary Numbers 8'S Colum 8'S Colum 2'S Colum 1'S 4'S Colum 4'S N N N N

Codes and number systems Introduction to Computer Yung-Yu Chuang with slides by Nisan & Schocken (www.nand2tetris.org) and Harris & Harris (DDCA) Coding • Assume that you want to communicate with your friend with a flashlight in a night, what will you do? light painting? What’s the problem? Solution #1 • A: 1 blink • B: 2 blibliknks • C: 3 blinks : • Z: 26 blinks Wha t’s the problem ? • How are you? = 131 blinks Solution #2: Morse code Hello Lookup • It is easy to translate into Morse code than reverse. Why? Lookup Lookup Useful for checking the correctness/ redddundency Braille Braille What’s common in these codes? • They are both binary codes. Binary representations • Electronic Implementation – Easy to store with bitblbistable elemen ts – Reliably transmitted on noisy and inaccurate wires 0 1 0 3.3V 2.8V 0.5V 0.0V Number systems <13> 1 Chapter = = Systems 2 1's column 10 1's column 10's column 2's column 100's column 4's column 1000's column 8's column 5374 1101 Number • numbers Decimal • Binary numbers Number Systems • Decimal numbers 1000's col 10's colum 1's column 100's colu u m n mn n 3 2 1 0 537410 = 5 ? 10 + 3 ? 10 + 7 ? 10 + 4 ? 10 five three seven four thousands hundreds tens ones • Binary numbers 8's colum 2's colum 1's colum 4's colum n n n n 3 2 1 0 11012 = 1 ? 2 + 1 ? 2 + 0 ? 2 + 1 ? 2 = 1310 one one no one eight four two one Chapter 1 <14> Binary numbers • Digits are 1 and 0 (a binary dig it is calle d a bit) 1 = true 0 = false • MSB –most significant bit • LSB –least significant bit MSB LSB • Bit numbering: 1 0 1 1 0 -

BCA SEM II CAO Data Representation and Number System by Dr. Rakesh Ranjan .Pdf.Pdf

Department Of Computer Application (BCA) Dr. Rakesh Ranjan BCA Sem - 2 Computer Organization and Architecture About Computer Inside Computers are classified according to functionality, physical size and purpose. Functionality, Computers could be analog, digital or hybrid. Digital computers process data that is in discrete form whereas analog computers process data that is continuous in nature. Hybrid computers on the other hand can process data that is both discrete and continuous. In digital computers, the user input is first converted and transmitted as electrical pulses that can be represented by two unique states ON and OFF. The ON state may be represented by a “1” and the off state by a “0”.The sequence of ON’S and OFF’S forms the electrical signals that the computer can understand. A digital signal rises suddenly to a peak voltage of +1 for some time then suddenly drops -1 level on the other hand an analog signal rises to +1 and then drops to -1 in a continuous version. Although the two graphs look different in their appearance, notice that they repeat themselves at equal time intervals. Electrical signals or waveforms of this nature are said to be periodic.Generally,a periodic wave representing a signal can be described using the following parameters Amplitude(A) Frequency(f) periodic time(T) Amplitude (A): this is the maximum displacement that the waveform of an electric signal can attain. Frequency (f): is the number of cycles made by a signal in one second. It is measured in hertz.1hert is equivalent to 1 cycle/second. Periodic time (T): the time taken by a signal to complete one cycle is called periodic time. -

Binary Slides

Decimal Numbers: Base 10 Numbers: positional notation Digits: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 • Number Base B ! B symbols per digit: • Base 10 (Decimal): 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Base 2 (Binary): 0, 1 Example: • Number representation: 3271 = • d31d30 ... d1d0 is a 32 digit number • value = d " B31 + d " B30 + ... + d " B1 + d " B0 (3x103) + (2x102) + (7x101) + (1x100) 31 30 1 0 • Binary: 0,1 (In binary digits called “bits”) • 0b11010 = 1"24 + 1"23 + 0"22 + 1"21 + 0"20 = 16 + 8 + 2 #s often written = 26 0b… • Here 5 digit binary # turns into a 2 digit decimal # • Can we find a base that converts to binary easily? CS61C L01 Introduction + Numbers (33) Garcia, Fall 2005 © UCB CS61C L01 Introduction + Numbers (34) Garcia, Fall 2005 © UCB Hexadecimal Numbers: Base 16 Decimal vs. Hexadecimal vs. Binary • Hexadecimal: Examples: 00 0 0000 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, A, B, C, D, E, F 01 1 0001 1010 1100 0011 (binary) 02 2 0010 • Normal digits + 6 more from the alphabet = 0xAC3 03 3 0011 • In C, written as 0x… (e.g., 0xFAB5) 04 4 0100 10111 (binary) 05 5 0101 • Conversion: Binary!Hex 06 6 0110 = 0001 0111 (binary) 07 7 0111 • 1 hex digit represents 16 decimal values = 0x17 08 8 1000 • 4 binary digits represent 16 decimal values 09 9 1001 0x3F9 "1 hex digit replaces 4 binary digits 10 A 1010 = 11 1111 1001 (binary) 11 B 1011 • One hex digit is a “nibble”. -

Tutorial on the Digital SENT Interface

A Tutorial for the Digital SENT Interface By Tim White, IDT System Architect SENT (Single Edge Nibble Transmission) is a unique serial interface originally targeted for automotive applications. First adopters are using this interface with sensors used for applications such as throttle position, pressure, mass airflow, and high temperature. The SENT protocol is defined to be output only. For typical safety-critical applications, the sensor data must be output at a constant rate with no bidirectional communications that could cause an interruption. For sensor calibration, a secondary interface is required to communicate with the device. In normal operation, the part is powered up and the transceiver starts transmitting the SENT data. This is very similar to the use model for an analog output with one important difference: SENT is not limited to one data parameter per transmission and can easily report multiple pieces of additional information, such as temperature, production codes, diagnostics, or other secondary data. Figure 1 Example of SENT Interface for High Temperature Sensing SENT Protocol Basic Concepts and Fast Channel Data Transmission The primary data are normally transmitted in what is typically called the “fast channel” with the option to simultaneously send secondary data in the “slow channel.” An example of fast channel transmission is shown in Figure 2. This example shows two 12-bit data words transmitted in each message frame. Many other options are also possible, such as 16 bits for signal 1 and 8 bits for signal 2. Synchronization/