10731605.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Secret Garden Issue July/August 2017

THE SECRET GARDEN ISSUE JULY/AUGUST 2017 IAM INFINITY #14 July/August 2017 Smiljana Gavrančić (Serbia) - Editor, Founder & Owner Victor Olliver (UK) - Associate from the Astrological Journal of the AA GB Sharon Knight (UK) - Associate from APAI Frank C. Clifford (UK) - Associate from the London School of Astrology Mandi Lockley (UK) - Associate from the Academy of Astrology UK Wendy Stacey (UK) - Associate from the Mayo School of Astrology and the AA GB Jadranka Ćoić (UK) - Associate from the Astrological Lodge of London Tem Tarriktar (USA) – Associate from The Mountain Astrologer magazine Athan J. Zervas (Greece) – Critique Partner/Associate for Art & Design 2 THE SECRET GARDEN ISSUE JULY/AUGUST 2017 3 THE SECRET GARDEN ISSUE JULY/AUGUST 2017 The iris means different things to different people and cultures. Some of its most common meanings are: Royalty Faith Wisdom Hope Valor Original photo by: Rudolf Ribarz (Austrian painter) – Irises 4 THE SECRET GARDEN ISSUE JULY/AUGUST 2017 www.londonschoolofastrology.co.uk 5 THE SECRET GARDEN ISSUE JULY/AUGUST 2017 CONTENTS 7 – IAM EDITOR‘S LETTER: „Destiny‘s Gate―; Electric Axis in Athens by Smiljana Gavrančić 11 – About Us 13 - Mikhail Gorbachev And Uranus Return In 2014; „The Guardian of Europe― by Smiljana Gavrančić 21 - IAM A GUEST: Roy Gillett & Victor Olliver 29 – IAM A GUEST: Nona Voudouri 34 – IAM A GUEST: Anne Whitaker 38 - The Personal is Political by Wendy Stacey 41 - 2017 August Eclipses forecasting by Rod Chang 48 - T – squares: An Introduction by Frank C. Clifford 57 - Astrology – -

Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept of Kingship

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Jacob Douglas Feeley University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Feeley, Jacob Douglas, "Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2276. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2276 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Josephus As Political Philosopher: His Concept Of Kingship Abstract Scholars who have discussed Josephus’ political philosophy have largely focused on his concepts of aristokratia or theokratia. In general, they have ignored his concept of kingship. Those that have commented on it tend to dismiss Josephus as anti-monarchical and ascribe this to the biblical anti- monarchical tradition. To date, Josephus’ concept of kingship has not been treated as a significant component of his political philosophy. Through a close reading of Josephus’ longest text, the Jewish Antiquities, a historical work that provides extensive accounts of kings and kingship, I show that Josephus had a fully developed theory of monarchical government that drew on biblical and Greco- Roman models of kingship. Josephus held that ideal kingship was the responsible use of the personal power of one individual to advance the interests of the governed and maintain his and his subjects’ loyalty to Yahweh. The king relied primarily on a standard array of classical virtues to preserve social order in the kingdom, protect it from external threats, maintain his subjects’ quality of life, and provide them with a model for proper moral conduct. -

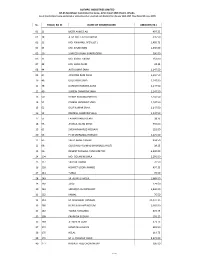

Sl. Folio/ Bo Id Name of Shareholder Amount (Tk.) 01 11

OLYMPIC INDUSTRIES LIMITED 62-63 Motijheel Commmercial Area, Amin Court (6th Floor), Dhaka. List of shareholders having unclaimed or undistributed or unsettled cash dividend for the year 2016-2017 (Year Ended 30 June, 2017) SL. FOLIO/ BO ID NAME OF SHAREHOLDER AMOUNT (TK.) 01 11 MEER AHMED ALI 497.25 02 18 A. M. MD. FAZLUR RAHIM 535.50 03 23 MD. ANWARUL AFZAL (JT.) 2,409.75 04 24 MD. AYUB KHAN 1,530.00 05 26 SHAHED HASAN SHARFUDDIN 306.00 06 31 MD. ABDUL HAKIM 153.00 07 38 MD. SHAH ALAM 38.25 08 44 AJIT KUMAR SAHA 1,147.50 09 45 JOSHODA RANI SAHA 1,147.50 10 46 DULU RANI SAHA 1,147.50 11 48 NARESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 12 49 SURESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 13 50 BENOY KRISHNA PODDER 1,147.50 14 51 PARESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 15 52 DILIP KUMAR SAHA 1,147.50 16 53 RAMESH CHANDRA SAHA 1,147.50 17 55 FARHAD BANU ISLAM 38.25 18 56 AMINUL ISLAM KHAN 765.00 19 61 SHEIKH MAHFUZ HOSSAIN 153.00 20 63 F I M MOFAZZAL HOSSAIN 5,125.50 21 65 SAJED AHMED KHAN 994.50 22 68 QUAZI MUHAMMAD SHAHIDULLAH (JT) 38.25 23 96 REGENT MOGHUL FUND LIMITED 6,300.00 24 104 MD. GOLAM MOWLA 2,295.00 25 117 SABERA ZAMAN 76.50 26 126 HEMYET UDDIN AHMED 497.25 27 141 TUBLA 76.50 28 149 SK. ALIMUL HAQUE 1,989.00 29 160 JALAL 229.50 30 161 SIDDIQUA CHOWDHURY 1,530.00 31 162 KAMAL 76.50 32 163 M. -

INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 1885-1947 Year Place President

INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 1885-1947 Year Place President 1885 Bombay W.C. Bannerji 1886 Calcutta Dadabhai Naoroji 1887 Madras Syed Badruddin Tyabji 1888 Allahabad George Yule First English president 1889 Bombay Sir William 1890 Calcutta Sir Pherozeshah Mehta 1891 Nagupur P. Anandacharlu 1892 Allahabad W C Bannerji 1893 Lahore Dadabhai Naoroji 1894 Madras Alfred Webb 1895 Poona Surendranath Banerji 1896 Calcutta M Rahimtullah Sayani 1897 Amraoti C Sankaran Nair 1898 Madras Anandamohan Bose 1899 Lucknow Romesh Chandra Dutt 1900 Lahore N G Chandravarkar 1901 Calcutta E Dinsha Wacha 1902 Ahmedabad Surendranath Banerji 1903 Madras Lalmohan Ghosh 1904 Bombay Sir Henry Cotton 1905 Banaras G K Gokhale 1906 Calcutta Dadabhai Naoroji 1907 Surat Rashbehari Ghosh 1908 Madras Rashbehari Ghosh 1909 Lahore Madanmohan Malaviya 1910 Allahabad Sir William Wedderburn 1911 Calcutta Bishan Narayan Dhar 1912 Patna R N Mudhalkar 1913 Karachi Syed Mahomed Bahadur 1914 Madras Bhupendranath Bose 1915 Bombay Sir S P Sinha 1916 Lucknow A C Majumdar 1917 Calcutta Mrs. Annie Besant 1918 Bombay Syed Hassan Imam 1918 Delhi Madanmohan Malaviya 1919 Amritsar Motilal Nehru www.bankersadda.com | www.sscadda.com| www.careerpower.in | www.careeradda.co.inPage 1 1920 Calcutta Lala Lajpat Rai 1920 Nagpur C Vijaya Raghavachariyar 1921 Ahmedabad Hakim Ajmal Khan 1922 Gaya C R Das 1923 Delhi Abul Kalam Azad 1923 Coconada Maulana Muhammad Ali 1924 Belgaon Mahatma Gandhi 1925 Cawnpore Mrs.Sarojini Naidu 1926 Guwahati Srinivas Ayanagar 1927 Madras M A Ansari 1928 Calcutta Motilal Nehru 1929 Lahore Jawaharlal Nehru 1930 No session J L Nehru continued 1931 Karachi Vallabhbhai Patel 1932 Delhi R D Amritlal 1933 Calcutta Mrs. -

Exploring Zechariah, Volume 2

EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 VOLUME ZECHARIAH, EXPLORING is second volume of Mark J. Boda’s two-volume set on Zechariah showcases a series of studies tracing the impact of earlier Hebrew Bible traditions on various passages and sections of the book of Zechariah, including 1:7–6:15; 1:1–6 and 7:1–8:23; and 9:1–14:21. e collection of these slightly revised previously published essays leads readers along the argument that Boda has been developing over the past decade. EXPLORING MARK J. BODA is Professor of Old Testament at McMaster Divinity College. He is the author of ten books, including e Book of Zechariah ZECHARIAH, (Eerdmans) and Haggai and Zechariah Research: A Bibliographic Survey (Deo), and editor of seventeen volumes. VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Boda Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-201-0) available at http://www.sbl-site.org/publications/Books_ANEmonographs.aspx Cover photo: Zev Radovan/BibleLandPictures.com Mark J. Boda Ancient Near East Monographs Monografías sobre el Antiguo Cercano Oriente Society of Biblical Literature Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente (UCA) EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 ANCIENT NEAR EAST MONOGRAPHS Editors Alan Lenzi Juan Manuel Tebes Editorial Board Reinhard Achenbach C. L. Crouch Esther J. Hamori Chistopher B. Hays René Krüger Graciela Gestoso Singer Bruce Wells Number 17 EXPLORING ZECHARIAH, VOLUME 2 The Development and Role of Biblical Traditions in Zechariah by Mark J. -

Constituent Assembly of India Debates (Proceedings) - Volume Ix

CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA DEBATES (PROCEEDINGS) - VOLUME IX Sunday, the 18th September 1949 __________ The Constituent Assembly of India met in the Constitution Hall, New Delhi, at Nine of the Clock, Mr. President (The Honourable Dr. Rajendra Prasad) in the Chair. ________ MOTION RE. OCTOBER MEETING OF ASSEMBLY Shri K. M. Munshi (Bombay: General) : Mr. President, Sir, may I move..... Shri Mahavir Tyagi (United Provinces : General) : Sir, lest it happens that there is no quorum during the course of the day, I would suggest that the date of the next meeting be first decided. Shri K. M. Munshi : Mr. Tyagi may have patience. I am moving : "That the President may be authorised to fix such a date in October as he considers suitable for the next meeting of the Constituent Assembly." Shri M. Thirumala Rao (Madras: General) : Why should we have it in October ? Shri K. M. Munshi : The meeting has to be held in October. I request the House to adopt the Resolution I have moved. Shri H. V. Kamath (C.P. & Berar: General) : May we know the probable date of the meeting in October? Mr. President : If the House is so pleased it may give me authority to call the next meeting at any date which I may consider necessary. I may provisionally announce that as at present advised I propose to all the next meeting to begin on 6th October. Due notice will be given to Members about it. An Honourable Member : How long will that session last ? Mr. President : It will up to 18th or 19th October. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

Son of the Desert

Dedicated to Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Shaheed without words to express anything. The Author SONiDESERT A biography of Quaid·a·Awam SHAHEED ZULFIKAR ALI H By DR. HABIBULLAH SIDDIQUI Copyright (C) 2010 by nAfllST Printed and bound in Pakistan by publication unit of nAfllST Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First Edition: April 2010 Title Design: Khuda Bux Abro Price Rs. 650/· Published by: Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/ Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives 4.i. Aoor, Sheikh Sultan Trust, Building No.2, Beaumont Road, Karachi. Phone: 021-35218095-96 Fax: 021-99206251 Printed at: The Time Press {Pvt.) Ltd. Karachi-Pakistan. CQNTENTS Foreword 1 Chapter: 01. On the Sands of Time 4 02. The Root.s 13 03. The Political Heritage-I: General Perspective 27 04. The Political Heritage-II: Sindh-Bhutto legacy 34 05. A revolutionary in the making 47 06. The Life of Politics: Insight and Vision· 65 07. Fall out with the Field Marshal and founding of Pakistan People's Party 108 08. The state dismembered: Who is to blame 118 09. The Revolutionary in the saddle: New Pakistan and the People's Government 148 10. Flash point.s and the fallout 180 11. Coup d'etat: tribulation and steadfasmess 197 12. Inside Death Cell and out to gallows 220 13. Home they brought the warrior dead 229 14. -

Key Principles of Public Sector Reforms

Key Principles of Public Sector Reforms Case Studies and Frameworks Key Principles of Public Sector Reforms Case Studies and Frameworks Advance proof copy. The final edition will be available in December 2016. © Commonwealth Secretariat 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher. Views and opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author and should in no way be attributed to the institutions to which they are affiliated or to the Commonwealth Secretariat. Wherever possible, the Commonwealth Secretariat uses paper sourced from responsible forests or from sources that minimise a destructive impact on the environment. Printed and published by the Commonwealth Secretariat. Table of contents Table of contents ........................................................................................ 1 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................... 3 Foreword .................................................................................................. 5 The Key Principles of Public Sector Reform ......................................................... 8 Principle 1. A new pragmatic and results–oriented framework ................................. 12 Case Study 1.1 South Africa. Measuring organisational productivity in the public service: North -

Dadabhai Naoroji: a Reformer of the British Empire Between Bombay and Westminster

Imperial Portaits Dadabhai Naoroji: A reformer of the British empire between Bombay and Westminster Teresa SEGURA-GARCIA ABSTRACT From the closing decades of the nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, Dadabhai Naoroji (1825‒1917) was India’s foremost intellectual celebrity — by the end of his career, he was known as ‘the Grand Old Man of India’. He spent most his life moving between western India and England in various capacities — as social reformer, academic, businessman, and politician. His life’s work was the redress of the inequalities of imperialism through political activism in London, at the heart of the British empire, where colonial policy was formulated. This project brought him to Westminster, where he became Britain’s first Indian member of parliament (MP). As a Liberal Party MP, he represented the constituency of Central Finsbury, London, from 1892 to 1895. Above all, he used the political structures, concepts, and language of the British empire to reshape it from within and, in this way, improve India’s political destiny. Dadabhai Naoroji, 1889. Naoroji wears a phenta, the distinctive conical hat of the Parsis. While he initially wore it in London, he largely abandoned it after 1886. This sartorial change was linked to his first attempt to reach Westminster, as one of his British collaborators advised him to switch to European hats. He ignored this advice: he mostly opted for an uncovered head, thus rejecting the colonial binary of the rulers versus the ruled. Source : National Portrait Gallery. Debate on the Indian Council Cotton Duties. by Sydney Prior Hall, published in The Graphic, 2 March 1895. -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking. -

Who Is Who in Pakistan & Who Is Who in the World Study Material

1 Who is Who in Pakistan Lists of Government Officials (former & current) Governor Generals of Pakistan: Sr. # Name Assumed Office Left Office 1 Muhammad Ali Jinnah 15 August 1947 11 September 1948 (died in office) 2 Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin September 1948 October 1951 3 Sir Ghulam Muhammad October 1951 August 1955 4 Iskander Mirza August 1955 (Acting) March 1956 October 1955 (full-time) First Cabinet of Pakistan: Pakistan came into being on August 14, 1947. Its first Governor General was Muhammad Ali Jinnah and First Prime Minister was Liaqat Ali Khan. Following is the list of the first cabinet of Pakistan. Sr. Name of Minister Ministry 1. Liaqat Ali Khan Prime Minister, Foreign Minister, Defence Minister, Minister for Commonwealth relations 2. Malik Ghulam Muhammad Finance Minister 3. Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar Minister of trade , Industries & Construction 4. *Raja Ghuzanfar Ali Minister for Food, Agriculture, and Health 5. Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar Transport, Communication Minister 6. Fazal-ul-Rehman Minister Interior, Education, and Information 7. Jogendra Nath Mandal Minister for Law & Labour *Raja Ghuzanfar’s portfolio was changed to Minister of Evacuee and Refugee Rehabilitation and the ministry for food and agriculture was given to Abdul Satar Pirzada • The first Chief Minister of Punjab was Nawab Iftikhar. • The first Chief Minister of NWFP was Abdul Qayum Khan. • The First Chief Minister of Sindh was Muhamad Ayub Khuro. • The First Chief Minister of Balochistan was Ataullah Mengal (1 May 1972), Balochistan acquired the status of the province in 1970. List of Former Prime Ministers of Pakistan 1. Liaquat Ali Khan (1896 – 1951) In Office: 14 August 1947 – 16 October 1951 2.