The Foraging Ecology of the Masked Booby in the Pacific Ocean

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher's Guide

The World Map / Selected Features of Political Geography Map No. 64 ISBN: 978-2-89157-186-9 PRODUCT NO.: 400 9288 Washable: We strongly recommend the use of Crayola water-soluble markers. Bands and hooks 122 cm × 94 cm / 48 in × 37 in Other markers may damage your maps. 120° 90° 60° T 9090° ° E S Bellingshausen E A 150° S Canada and the World W Sea SOUTH ANTARCTIC I A N F E D E R T ARCTIC SHETLAND ISLANDS S S A T I O R U N Amundsen AT Yenisei ALEXANDER L a 120° A N n Sea N e ISLAND T 30° L IC The Base Map L e n O a Tiksi C THURSTON E A ISLAND N 70° Khatanga N e n l Salekhard Weddell rc ia i 60° C rth L id c swo and Sea r ti Ob Ell e c Map No. 64 A r Laptev Ronne n im 180° N A t ta n A an Ice Shelf r E ri Sea c A e t C ib THE WORLD ic A • S Contours and outlines are O l C N a NEW SIBERIAN ISLANDS BERKNER i Pevek t a Kara 70° r C e c T I n p A e S [RUSSIAN FEDERATION] a l F ri Sea ISLAND e R I C O r C C selected features of political geography 150° la T 80° A scale: 1 / 40 000 000 scale: 1 / 40 000 000 o I P P Coats Land C WRANGEL 0° Be N O ring Str ISLAND N 0 1 000 km 0 1 000 km carefully stylized to capture ait O V C A A Y A M L Y 80 [RUSSIAN FEDERATION] Z E 90° 100° 110 ° 120° 130° 140° 150° 160° 170° 180° 170° 160° 150° 140° 130° 120° 110 ° 100° 90° 80° 70° 60° 50° 40° 30° 20° 10° 0° 10° 20° 30° 40° 50° 60° 70° 80° ° E Arkhangelsk Queen Maud A Land N ARCTIC OCEAN Chukchi Barents N Ross Amundsen-Scott azimuthal equidistant projection azimuthal equidistant projection A Sea Sea 80 E Sea [U.S.A.] ° C ALASKA 70° 80° O the essentials. -

The Political Biogeography of Migratory Marine Predators

1 The political biogeography of migratory marine predators 2 Authors: Autumn-Lynn Harrison1, 2*, Daniel P. Costa1, Arliss J. Winship3,4, Scott R. Benson5,6, 3 Steven J. Bograd7, Michelle Antolos1, Aaron B. Carlisle8,9, Heidi Dewar10, Peter H. Dutton11, Sal 4 J. Jorgensen12, Suzanne Kohin10, Bruce R. Mate13, Patrick W. Robinson1, Kurt M. Schaefer14, 5 Scott A. Shaffer15, George L. Shillinger16,17,8, Samantha E. Simmons18, Kevin C. Weng19, 6 Kristina M. Gjerde20, Barbara A. Block8 7 1University of California, Santa Cruz, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Long 8 Marine Laboratory, Santa Cruz, California 95060, USA. 9 2 Migratory Bird Center, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, National Zoological Park, 10 Washington, D.C. 20008, USA. 11 3NOAA/NOS/NCCOS/Marine Spatial Ecology Division/Biogeography Branch, 1305 East 12 West Highway, Silver Spring, Maryland, 20910, USA. 13 4CSS Inc., 10301 Democracy Lane, Suite 300, Fairfax, VA 22030, USA. 14 5Marine Mammal and Turtle Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine 15 Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Moss Landing, 16 California 95039, USA. 17 6Moss Landing Marine Laboratories, Moss Landing, CA 95039 USA 18 7Environmental Research Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine 19 Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 99 Pacific Street, 20 Monterey, California 93940, USA. 21 8Hopkins Marine Station, Department of Biology, Stanford University, 120 Oceanview 22 Boulevard, Pacific Grove, California 93950 USA. 23 9University of Delaware, School of Marine Science and Policy, 700 Pilottown Rd, Lewes, 24 Delaware, 19958 USA. 25 10Fisheries Resources Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, National Marine 26 Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, La Jolla, CA 92037, 27 USA. -

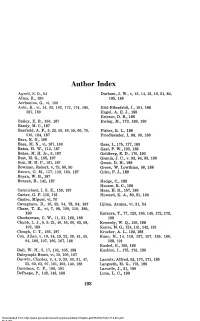

Author Index

Author Index Agrell, S. 0., 54 Durham, J. W., v, 13, 14, 15, 16, 51, 84, Allen, R., 190 105, 188 Arrhenius, G., vi, 169 Aoki, K, vi, 14, 52, 162, 172, 174, 185, Eibl-Eibesfeldt, I., 101, 188 187, 189 Engel, A. E. J., 188 Ericson, D. B., 188 Bailey, E. B., 166, 187 Ewing, M., 170, 188, 189 Bandy, M. C., 187 Banfield, A. F., 5, 22, 55, 56, 59, 60, 70, Fisher, R. L., 188 110, 124, 187 Friedlaender, I, 98, 99, 188 Barr, K. G., 190 Bass, M. N., vi, 167, 169 Gass, I., 175, 177, 189 Bates, H. W., 113, 187 Gast, P. W., 133, 188 Behre, M. H. Jr., 5, 187 Goldberg, E. D., 170, 190 Best, M. G„ 165, 187 Granja, J. C., v, 83, 84, 85, 188 Bott, M. H. P., 181, 187 Green, D. H., 188 Bowman, Robert, v, 79, 80, 90 Green, W. Lowthian, 98, 188 Brown, G. M., 157, 159, 160, 187 Grim, P. J., 189 Bryan, W. B., 187 Bunsen, R., 141, 187 Hedge, C., 188 Heezen, B. C., 188 Carmichael, I. S. E., 159, 187 Hess, H. H„ 157, 188 Carter, G. F. 115, 191 Howard, K. A., 80, 81,190 Castro, Miguel, vi, 76 Cavagnaro, D., 16, 33, 34, 78, 94, 187 Iljima, Azuma, vi, 31, 54 Chase, T. E., vi, 7, 98, 109, 110, 189, 190 Katsura, T., 77, 125, 136, 145, 172, 173, Chesterman, C. W., 11, 31, 168, 188 189 Chubb, L. J., 5, 9, 21, 46, 55, 60, 63, 98, Kennedy, W. -

Marine Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots

RESEARCH ARTICLE Marine Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots Alan M. Friedlander1,2,3*, Enric Ballesteros4, Jennifer E. Caselle5, Carlos F. Gaymer3,6,7,8, Alvaro T. Palma9, Ignacio Petit6, Eduardo Varas9, Alex Muñoz Wilson10, Enric Sala1 1 Pristine Seas, National Geographic Society, Washington, District of Columbia, United States of America, 2 Fisheries Ecology Research Lab, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii, United States of America, 3 Millennium Nucleus for Ecology and Sustainable Management of Oceanic Islands (ESMOI), Coquimbo, Chile, 4 Centre d'Estudis Avançats (CEAB-CSIC), Blanes, Spain, 5 Marine Science Institute, University of California Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, California, United States of America, 6 Universidad Católica del Norte, Coquimbo, Chile, 7 Centro de Estudios Avanzados en Zonas Áridas, Coquimbo, Chile, 8 Instituto de Ecología y Biodiversidad, Coquimbo, Chile, 9 FisioAqua, Santiago, Chile, 10 OCEANA, SA, Santiago, Chile * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Friedlander AM, Ballesteros E, Caselle JE, Gaymer CF, Palma AT, Petit I, et al. (2016) Marine The Juan Fernández and Desventuradas islands are among the few oceanic islands Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas belonging to Chile. They possess a unique mix of tropical, subtropical, and temperate Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots. PLoS marine species, and although close to continental South America, elements of the biota ONE 11(1): e0145059. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0145059 have greater affinities with the central and south Pacific owing to the Humboldt Current, which creates a strong biogeographic barrier between these islands and the continent. The Editor: Christopher J Fulton, The Australian National University, AUSTRALIA Juan Fernández Archipelago has ~700 people, with the major industry being the fishery for the endemic lobster, Jasus frontalis. -

Bryozoa De La Placa De Nazca Con Énfasis En Las Islas Desventuradas

Cienc. Tecnol. Mar, 28 (1): 75-90, 2005 Bryozoa de la Placa de Nazca 75 BRYOZOA DE LA PLACA DE NAZCA CON ÉNFASIS EN LAS ISLAS DESVENTURADAS ON THE NAZCA PLATE BRYOZOANS WITH EMPHASIS ON DESVENTURADAS ISLANDS HUGO I. MOYANO G. Departamento de Zoología Universidad de Concepción Casilla 160-C Concepción Recepción: 27 de abril de 2004 – Versión corregida aceptada: 1 de octubre de 2004. RESUMEN Esta es una revisión parcial de las faunas de briozoos conocidas hasta ahora provenientes de la Placa de Nazca. A partir de las publicaciones preexistentes y del examen de algunas muestras se compa- raron zoogeográficamente Pascua (PAS), Salas y Gómez (SG), Juan Fernández (JF), Desventuradas (DES) y Galápagos (GAL). Para la comparación se utilizaron tres conjuntos de 115, 140 y 170 géneros de los territorios insulares ya indicados, los que incluyen también aquellos de las costas chileno-peruanas influi- das por la corriente de Humboldt (CHP) y los de las islas Kermadec (KE). Los dendrogramas resultantes demuestran que los territorios insulares más afines son los de Juan Fernández y las Desventuradas en términos de afinidad genérica briozoológica. El dendrograma basado en 170 géneros de los órdenes Ctenostomatida y Cheilostomatida muestra dos conjuntos principales a saber: a) JF, DES y CHP y b) PAS, GA y KE a los cuales se une solitariamente SG. Sobre la base de la comparación a nivel genérico indicada más arriba, para las islas Desventura- das no se justifica un status zoogeográfico separado de nivel de provincia tropical sino que debería integrarse a la provincia temperado-cálida de Juan Fernández. -

Redalyc.Initial Assessment of Coastal Benthic Communities in the Marine Parks at Robinson Crusoe Island

Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research E-ISSN: 0718-560X [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Chile Rodríguez-Ruiz, Montserrat C.; Andreu-Cazenave, Miguel; Ruz, Catalina S.; Ruano- Chamorro, Cristina; Ramírez, Fabián; González, Catherine; Carrasco, Sergio A.; Pérez- Matus, Alejandro; Fernández, Miriam Initial assessment of coastal benthic communities in the Marine Parks at Robinson Crusoe Island Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research, vol. 42, núm. 4, octubre, 2014, pp. 918-936 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso Valparaíso, Chile Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=175032366016 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res., 42(4): 918-936, 2014 Marine parks at Robinson Crusoe Island 918889 “Oceanography and Marine Resources of Oceanic Islands of Southeastern Pacific ” M. Fernández & S. Hormazábal (Guest Editors) DOI: 10.3856/vol42-issue4-fulltext-16 Research Article Initial assessment of coastal benthic communities in the Marine Parks at Robinson Crusoe Island Montserrat C. Rodríguez-Ruiz1, Miguel Andreu-Cazenave1, Catalina S. Ruz2 Cristina Ruano-Chamorro1, Fabián Ramírez2, Catherine González1, Sergio A. Carrasco2 Alejandro Pérez-Matus2 & Miriam Fernández1 1Estación Costera de Investigaciones Marinas and Center for Marine Conservation, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, P.O. Box 114-D, Santiago, Chile 2Subtidal Ecology Laboratory and Center for Marine Conservation, Estación Costera de Investigaciones Marinas, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, P.O. Box 114-D, Santiago, Chile ABSTRACT. -

Radiocarbon Ages of Lacustrine Deposits in Volcanic Sequences of the Lomas Coloradas Area, Socorro Island, Mexico

Radiocarbon Ages of Lacustrine Deposits in Volcanic Sequences of the Lomas Coloradas Area, Socorro Island, Mexico Item Type Article; text Authors Farmer, Jack D.; Farmer, Maria C.; Berger, Rainer Citation Farmer, J. D., Farmer, M. C., & Berger, R. (1993). Radiocarbon ages of lacustrine deposits in volcanic sequences of the Lomas Coloradas area, Socorro Island, Mexico. Radiocarbon, 35(2), 253-262. DOI 10.1017/S0033822200064924 Publisher Department of Geosciences, The University of Arizona Journal Radiocarbon Rights Copyright © by the Arizona Board of Regents on behalf of the University of Arizona. All rights reserved. Download date 28/09/2021 10:52:25 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/653375 [RADIOCARBON, VOL. 35, No. 2, 1993, P. 253-262] RADIOCARBON AGES OF LACUSTRINE DEPOSITS IN VOLCANIC SEQUENCES OF THE LOMAS COLORADAS AREA, SOCORRO ISLAND, MEXICO JACK D. FARMERI, MARIA C. FARMER2 and RAINER BERGER3 ABSTRACT. Extensive eruptions of alkalic basalt from low-elevation fissures and vents on the southern flank of the dormant volcano, Cerro Evermann, accompanied the most recent phase of volcanic activity on Socorro Island, and created 14C the Lomas Coloradas, a broad, gently sloping terrain comprising the southern part of the island. We obtained ages of 4690 ± 270 BP (5000-5700 cal BP) and 5040 ± 460 BP (5300-6300 cal BP) from lacustrine deposits that occur within volcanic sequences of the lower Lomas Coloradas. Apparently, the sediments accumulated within a topographic depression between two scoria cones shortly after they formed. The lacustrine environment was destroyed when the cones were breached by headward erosion of adjacent stream drainages. -

Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences

STREAMS - Research Opportunities in Biomedical Sciences WSU Boonshoft School of Medicine 3640 Colonel Glenn Highway Dayton, OH 45435-0001 APPLICATION (please type or print legibly) *Required information *Name_____________________________________ Social Security #____________________________________ *Undergraduate Institution_______________________________________________________________________ *Date of Birth: Class: Freshman Sophomore Junior Senior Post-bac Major_____________________________________ Expected date of graduation___________________________ SAT (or ACT) scores: VERB_________MATH_________Test Date_________GPA__________ *Applicant’s Current Mailing Address *Mailing Address After ____________(Give date) _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ _________________________________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Phone # : Day (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ Eve (____)_______________________ *Email Address:_____________________________ FAX number: (____)_______________________ Where did you learn about this program?:__________________________________________________________ *Are you a U.S. citizen or permanent resident? Yes No (You must be a citizen or permanent resident to participate in this program) *Please indicate the group(s) in which you would include yourself: Native American/Alaskan Native Black/African-American -

Parque Nacional Revillagigedo

EVALUATION REPORT Parque Nacional Revillagigedo Location: Revillagigedo Archipelago, Mexico, Eastern Pacific Ocean Blue Park Status: Nominated (2020), Evaluated (2021) MPAtlas.org ID: 68808404 Manager(s): Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (CONANP) MAPS 2 1. ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA 1.1 Biodiversity Value 4 1.2 Implementation 8 2. AWARD STATUS CRITERIA 2.1 Regulations 11 2.2 Design, Management, and Compliance 13 3. SYSTEM PRIORITIES 3.1 Ecosystem Representation 18 3.2 Ecological Spatial Connectivity 18 SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION: Evidence of MPA Effects 19 Figure 1: Revillagigedo National Park, located 400 km south of Mexico’s Baja peninsula, covers 148,087 km2 and includes 3 zone types – Research (solid blue), Tourism (dotted), and Traditional Use/Naval (lined) – all of which ban all extractive activities. It is partially surrounded by the Deep Mexican Pacific Biosphere Reserve (grey) which protects the water column below 800 m. All 3 zones of the National Park are shown in the same shade of dark blue, reflecting that they all have Regulations Based Classification scores ≤ 3, corresponding with a fully protected status (see Section 2.1 for more information about the regulations associated with these zones). (Source: MPAtlas, Marine Conservation Institute) 2 Figure 2: Three-dimensional map of the Revillagigedo Marine National Park shows the bathymetry around Revillagigedo’s islands. (Source: Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas, 2018) 3 1.1 Eligibility Criteria: Biodiversity Value (must satisfy at least one) 1.1.1. Includes rare, unique, or representative ecosystems. The Revillagigedo Archipelago is comprised of a variety of unique ecosystems, due in part to its proximity to the convergence of five tectonic plates. -

Archipiélago De Revillagigedo

LATIN AMERICA / CARIBBEAN ARCHIPIÉLAGO DE REVILLAGIGEDO MEXICO Manta birostris in San Benedicto - © IUCN German Soler Mexico - Archipiélago de Revillagigedo WORLD HERITAGE NOMINATION – IUCN TECHNICAL EVALUATION ARCHIPIÉLAGO DE REVILLAGIGEDO (MEXICO) – ID 1510 IUCN RECOMMENDATION TO WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: To inscribe the property under natural criteria. Key paragraphs of Operational Guidelines: Paragraph 77: Nominated property meets World Heritage criteria (vii), (ix) and (x). Paragraph 78: Nominated property meets integrity and protection and management requirements. 1. DOCUMENTATION (2014). Evaluación de la capacidad de carga para buceo en la Reserva de la Biosfera Archipiélago de a) Date nomination received by IUCN: 16 March Revillagigedo. Informe Final para la Direción de la 2015 Reserva de la Biosiera, CONANP. La Paz, B.C.S. 83 pp. Martínez-Gomez, J. E., & Jacobsen, J.K. (2004). b) Additional information officially requested from The conservation status of Townsend's shearwater and provided by the State Party: A progress report Puffinus auricularis auricularis. Biological Conservation was sent to the State Party on 16 December 2015 116(1): 35-47. Spalding, M.D., Fox, H.E., Allen, G.R., following the IUCN World Heritage Panel meeting. The Davidson, N., Ferdaña, Z.A., Finlayson, M., Halpern, letter reported on progress with the evaluation process B.S., Jorge, M.A., Lombana, A., Lourie, S.A., Martin, and sought further information in a number of areas K.D., McManus, E., Molnar, J., Recchia, C.A. & including the State Party’s willingness to extend the Robertson, J. (2007). Marine ecoregions of the world: marine no-take zone up to 12 nautical miles (nm) a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. -

The Status of Clipperton Atoll Under International Law, and the Right to Fish in Its Surrounding Waters

.. ~ The Status of Clipperton Atoll Under International Law, and the Right to Fish in Its Surrounding Waters by Jon M. Van Dyke 2515 Dole Street Honolulu, Hawai'i 96822 [email protected] May 15,2006 Introduction. Remote and tiny Clipperton Atoll is 1,120 kilometers southwest of Mexico. 1 Its land area forms a circle with an average width of about 200 meters and a circumference of about 12 kilometers, making up about 1.6 square kilometers of land area. If its stagnant brackish-water interior lagoon is also included it measures about six square kilometers, 12 times larger than the size of The Mall in Washington, D.C? The Atoll had been located earlier by Spanish navigators, but was named after the English pirate John Clipperton who was said to have hidden there in 1705 with 21 other mutineers.3 The French claim of sovereignty over Clipperton is based on a visit to the atoll in November 1858 by the merchant ship L 'Amiral, operated by a French shipowner named Lockhart and carrying the French Lieutenant Victor Ie Coat de Kerveguen who was authorized by Napoleon III to assert sovereignty over guano islands.4 The crew landed, after considerable difficulty, in a small boat, sampled the guano deposits (finding that they were not rich in phosphates), and left no permanent plaque on shore. When L 'Amiral arrived in Honolulu, Hawaii the next month, its crew published a IU.S. Central Intelligence Agency, Clipperton Island in THE WORLD FACTBOOK, <http://www.cia.gov/ciaJpublications/factbookigeos/ip.html> (site visited May 9, 2006). -

Marjorie L. Reaka and Raymond B. Manning

SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE MARINE SCIENCES • NUMBER 7 The Distributional Ecology and Zoogeographical Relationships of Stomatopod Crustacea from Pacific Costa Rica Marjorie L. Reaka and Raymond B. Manning Oil -7 1980 SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1980 The Distributional Ecology and Zoogeographical Relationships of Stomatopod Crustacea from Pacific Costa Rica Marjorie L. Reaka and Raymond B. Manning Introduction not the West Atlantic; and species in several other East Pacific stomatopod genera (Eurysquilla, Co- The biota of the East Pacific region is relatively ronida, Lysiosquilla, and Pseudosquillopsis) show clos poorly known, despite its considerable zoogeo- est affinities to species in the East Atlantic (Man graphic significance. The East Pacific has been ning, 1977). On the other hand, some species of separated from the West Atlantic region since the mollusks occur in the Atlantic and Indo-West late Miocene (Durham and Allison, 1960; Wood- Pacific, but not the East Pacific (see Woodring, ring, 1966), and, although high levels of ende- 1966; Emerson, 1978). Species of four stomatopod mism are found there, many East Pacific species genera (Bathysquilla, Odontodactylus, Alima, Pseudo- show affinities to taxa in the West Atlantic squilla) are present in the West Atlantic and Indo- (Woodring, 1966; Briggs, 1974; Manning, 1977; West Pacific, but not in the East Pacific (Man Emerson, 1978). However, some East Pacific spe ning, 1969a; Manning and Struhsaker, 1976). An cies are more closely related to taxa in the East alpheid shrimp, Alpheus paracrinitus Miers, 1881, is Atlantic than to those in the West Atlantic. For known from the Indo-West Pacific, Clipperton example, a xanthid crab, Nanocassiope melanodactyla (A.