New Strategies for the Optimal Use of Platelet Transfusions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines for Transfusions

Guidelines for Transfu- sion Prepared by: Community Transfusion Committee Lincoln, Nebraska CHAIR: Aina Silenieks, MD MEMBERS: L. Bausch, M.D. R. Burton, M.D. S. Dunder, M.D. D. Voigt, M.D. B. J. Wilson, M.D. COMMUNITY Becky Croner REPRESENTATIVES: Ellen DiSalvo Christa Engel Phyllis Ericson Kelly Gillaspie Pat Gilles Vic Grdina Jessica Henrichs Kelly Jensen Laurel McReynolds Christina Nickel Angela Novotny Kelley Thiemann Janet Wachter Jodi Wikoff Guidelines For Transfusion Community Transfusion Committee INTRODUCTION The Community Transfusion Committee is a multidisciplinary group that meets to monitor blood utilization practices, establish guidelines for transfusion and discuss relevant transfusion related topics. It is comprised of physicians from local hospitals, invited guests, and community representatives from the hospitals’ transfusion services, nursing services, perfusion services, health information management, and the Nebraska Community Blood Bank. These Guidelines for Transfusion are reviewed and revised biannually by the Community Trans- fusion Committee to ensure that the industry’s most current practices are promoted. The Guidelines are the standard by which utilization practices are evaluated. They are also de- signed to provide helpful information to assist physicians to provide appropriate blood compo- nent therapy to patients. Appendices have been added for informational purposes and are not to be used as guidance for clinical decision making. ADULT RED CELLS A. Indications 1. One of the following a. Hypovolemia and hypoxia (signs/symptoms: syncope, dyspnea, postural hypoten- sion, tachycardia, angina, or TIA) secondary to surgery, trauma, GI tract bleeding, or intravascular hemolysis, OR b. Evidence of acute loss of 15% of total blood volume or >750 mL blood loss, OR c. -

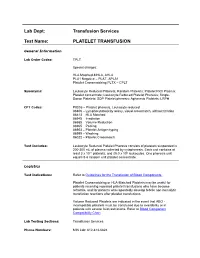

Platelet Transfusion

Lab Dept: Transfusion Services Test Name: PLATELET TRANSFUSION General Information Lab Order Codes: TPLT Special charges: HLA Matched-MHLA, AHLA PLA1 Negative – PLAT, APLA1 Platelet Crossmatching PLTX – CPLT Synonyms: Leukocyte Reduced Platelets; Random Platelets; Platelet Rich Plasma; Platelet concentrate; Leukocyte Reduced Platelet Pheresis; Single- Donor Platelets; SDP Platelet pheresis; Apheresis Platelets; LRPH CPT Codes: P9035 – Platelet pheresis, Leukocyte reduced 86806 – Lymphocytotoxicity assay, visual crossmatch, without titration 86813 – HLA Matched 86945 – Irradiation 86985 – Volume Reduction 86965 – Pooling 86903 – Platelet Antigen typing 86999 – Washing 86022 – Platelet Crossmatch Test Includes: Leukocyte Reduced Platelet Pheresis consists of platelets suspended in 200-300 mL of plasma collected by cytapheresis. Each unit contains at least 3 x 1011 platelets, and ≤5.0 x 106 leukocytes. One pheresis unit equals 5-6 random unit platelet concentrate. Logistics Test Indications: Refer to Guidelines for the Transfusion of Blood Components. Platelet Crossmatching or HLA-Matched Platelets may be useful for patients receiving repeated platelet transfusions who have become refractile, and for patients who repeatedly develop febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reactions after platelet transfusions. Volume Reduced Platelets are indicated in the event that ABO - incompatible platelets must be transfused due to availability or in patients with severe fluid restrictions. Refer to Blood Component Compatibility Chart Lab Testing Sections: Transfusion Services Phone Numbers: MIN Lab: 612-813-6824 STP Lab: 651-220-6558 Test Availability: Daily, 24 hours Turnaround Time: 1 - 2 hours Standard Dose/Volume: <10 kg: 10 – 15 mL/kg up to one unit or 50 mL maximum 10 – 15 kg: 1/3 pheresis unit 15 – 25 kg: 1/2 pheresis unit >25 kg: 1 pheresis unit Rate of Infusion: 10 minutes/unit, <4 hours Administration: Must be administered through a blood component administration filter. -

Blood Product Modifications: Leukofiltration, Irradiation and Washing

Blood Product Modifications: Leukofiltration, Irradiation and Washing 1. Leukocyte Reduction Definitions and Standards: o Process also known as leukoreduction, or leukofiltration o Applicable AABB Standards, 25th ed. Leukocyte-reduced RBCs At least 85% of original RBCs < 5 x 106 WBCs in 95% of units tested . Leukocyte-reduced Platelet Concentrates: At least 5.5 x 1010 platelets in 75% of units tested < 8.3 x 105 WBCs in 95% of units tested pH≥6.2 in at least 90% of units tested . Leukocyte-reduced Apheresis Platelets: At least 3.0 x 1011 platelets in 90% of units tested < 5.0 x 106 WBCs 95% of units tested pH≥6.2 in at least 90% of units tested Methods o Filter: “Fourth-generation” filters remove 99.99% WBCs o Apheresis methods: most apheresis machines have built-in leukoreduction mechanisms o Less efficient methods of reducing WBC content . Washing, deglycerolizing after thawing a frozen unit, centrifugation . These methods do not meet requirement of < 5.0 x 106 WBCs per unit of RBCs/apheresis platelets. Types of leukofiltration/leukoreduction o “Pre-storage” . Done within 24 hours of collection . May use inline filters at time of collection (apheresis) or post collection o “Pre-transfusion” leukoreduction/bedside leukoreduction . Done prior to transfusion . “Bedside” leukoreduction uses gravity-based filters at time of transfusion. Least desirable given variability in practice and absence of proficiency . Alternatively performed by transfusion service prior to issuing Benefits of leukoreduction o Prevention of alloimmunization to donor HLA antigens . Anti-HLA can mediate graft rejection and immune mediated destruction of platelets o Leukoreduced products are indicated for transplant recipients or patients who are likely platelet transfusion dependent o Prevention of febrile non-hemolytic transfusion reactions (FNHTR) . -

Transfusion Triggers for Platelets and Other Blood Products Sunil Karanth Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine (2019): 10.5005/Jp-Journals-10071-23250

INVITED ARTICLE Transfusion Triggers for Platelets and Other Blood Products Sunil Karanth Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine (2019): 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23250 INTRODUCTION Department of Intensive Care Unit, Manipal Hospital, Bengaluru, Transfusion of whole blood is not associated with any significant Karnataka, India benefit, rather can be harmful. Significant advances have been Corresponding Author: Sunil Karanth, Department of Intensive made in transfusion medicine, facilitating the use of blood product Care Unit, Manipal Hospital, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India, e-mail: or component therapy than use of whole blood (Fig. 1). In 2009, a [email protected] report on Serious Hazards of Transfusion in the UK, estimated that How to cite this article: Karanth S. Transfusion Triggers for Platelets a total of 3 million units of blood components were released. The and Other Blood Products. Indian J Crit Care Med 2019;23(Suppl requirement of the same in South-East Asia is much higher to the 3):S189–S190. tune of 15 million units annually. The current recommendation Source of support: Nil is to use blood only in life-threatening situations, rather than to Conflict of interest: None normalize abnormal numbers. PLATELETS Platelets are derived from the buffy coat of whole blood donations. A pooled platelet concentrate includes pooled buffy-coat derived platelets from four whole-blood donations suspended in platelet additive solution and plasma of one of the four donors. It contains 240000 platelets pooled from 4–6 donors. A Single donor platelet is derived from a single-donor by a process of apheresis. In view of the lesser number of donors and the theoretical advantage of involving a single-donor platelet (SDP) may be preferred over the use of platelets from multiple donors. -

Blood-Platelet-Orders-Outpatient-V3

Blood / Platelet Orders Outpt v3 USE THIS ORDER SET FOR OUTPATIENT NON URGENT BLOOD OR PLATELET TRANSFUSION 24 Hours advanced notice required for infusion center NO MORE THAN 2 UNITS OF RED BLOOD CELLS CAN BE INFUSED IN THE INFUSION CENTER PER DAY BMH Outpatient Infusion Center: Fax completed order set to 843-522-7313/Phone 843-522-7680 Hospital Outpatient: Fax Completed order set to Registration at 843-522-5741 and notify Nursing Supervisor at 843-522-7653 Service Designation THIS IS NOT AN ADMISSION SET Patient Name ___________________________________ Patient DOB ____________ Service Designation Blood Platelet Outpatient Attending ___________________________________ Date Requested ___________________________________ Status Outpatient Check Appropriate Diagnosis Below: [ Anemia of chronic renal disease Anemia related to chemotherapy Aplastic anemia Anemia related to cancer Anemia related to blood loss Sickle cell disease Anemia unspecified Thombocytopenia (platelets) Other _________________________ ] Allergies Update Allergies in the Summary Panel in MEDITECH Special Requirement: (REQUIRES SPECIAL ORDER ONE DAY IN ADVANCE) Special Requirement RBC or Platelets REQUIRES SPECIAL ORDER ONE DAY IN ADVANCE [ Irradiated CMV Negative HgBS Negative ] Medications diphenhydrAMINE HCl (Benadryl) 25 mg orally single dose premedicate prior to transfusion diphenhydrAMINE HCl (Benadryl) 50 mg orally single dose premedicate prior to transfusion diphenhydrAMINE HCl (Benadryl) 25 mg intravenously single dose premedicate prior to transfusion diphenhydrAMINE -

Platelet Transfusion Refractoriness

Evaluation of the Patient with Suspected Platelet Refractory State NOTE: While evaluating the patient for suspected immune refractory state, provide ABO matched platelets if available. 1. Determine if the Alloimmunization may be directed against platelet specific antigens or, more commonly HLA patient is at risk for antigens. Current leukoreduction methods are generally effective at preventing HLA alloimmunization: alloimmunization. Alloimmunization may occur in multiply transfused patients. A. Multiparous female? B. Multiple nonleukoreduced transfusions? C. Organ transplant? Assess previous platelet transfusions: TWO previous ABO compatible/ABO matched transfusions fail to yield an increase in platelet count >10K or a CCI >5-7500 Platelet counts should be performed 10 – 60 minutes post transfusion and 24 hour post transfusion. One hour post transfusion platelet counts that fail to demonstrate a >10K increase in platelets is suggestive of immune destruction. Adequate one hour post transfusion platelet counts and decreased 24 hour post transfusion platelet counts are suggestive of consumption/utilization/sequestration. Condition Presentation Laboratory Findings 2. Exclude non- alloimmune causes Leukocytosis, +cultures Sepsis Fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, etc. of a platelet refractory state: Thrombocytopenia, elevated PT, APTT, decreased DIC Bleeding, oozing These are generally fibrinogen, + fibrin degradation disorders of platelet products consumption. Sequestration Splenomegaly . Antibiotics (esp Vancomycin) Drugs are an often . Heparin (Heparin induced Thrombocytopenia, diminished overlooked cause of Drugs thrombocytopenia)* response to transfusion platelet destruction. Amphotericin . Purpura, esp of lower extremities Thrombocytopenia Auto-Immune . Easy bruising Auto antibodies to platelet thrombocytopenia* Nose bleeds glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (aka ITP) . Bleeding gums Significant bleeding may consume Thrombocytopenia, diminished Bleeding platelets response to transfusion Continued on next page TS 017 (Rev. -

Comparing Platelet Compatibility to Red Cell Compatibility Protocols

Review: comparing platelet compatibility to red cell compatibility protocols S. ROLIH Between 1971 and 1980, the number of platelet con- Incidence of Alloimmunization From centrates transfused in the United States increased from Transfusion 0.4 to 2.8 million units.1 That number increased to near- Each RBC or platelet transfusion has the potential to ly 5 million in 1987 and continues to increase in the influence the outcome of future transfusions of the 1990s. The increase in platelet transfusions has led to a same products by inducing the formation of alloanti- concomitant rise in the incidence of platelet alloimmu- bodies. For RBC transfusions, in which ABO and D nization. As a consequence, many transfusion services group-compatible units are routinely given, this is not a or blood product providers have developed platelet significant problem. Only 0.3 percent to 1.3 percent of compatibility protocols to select platelet components all RBC transfusion recipients produce alloantibodies, that will have acceptable survival when transfused to although in selected recipient populations, such as alloimmunized patients. Most serologists are familiar patients with thalassemia or sickle cell anemia, the with compatibility tests used to select red blood cells alloimmunization rate may be as high as 30 percent (RBCs) for transfusion. These tests are performed before because of chronic transfusions.2 Overall, decreased sur- transfusion, whether or not alloimmunization has vival of transfused RBCs due to alloimmunization occurs occurred. Platelet compatibility tests, in contrast, are infrequently. Once alloimmunization occurs, premature implemented only after alloimmunization and develop- loss of future transfused RBCs is prevented by the selec- ment of the refractory state. -

Outpatient Blood Platelet Orders

Blood / Platelet Orders Outpt v5 USE THIS ORDER SET FOR OUTPATIENT NON URGENT BLOOD OR PLATELET TRANSFUSION 24 Hours advanced notice required for infusion center NO MORE THAN 2 UNITS OF RED BLOOD CELLS CAN BE INFUSED AS AN OUTPATIENT PER DAY BMH Outpatient Infusion Center: Fax completed order set to 843-522-7313/Phone 843-522-7680 Hospital Outpatient: Fax Completed order set to Registration at 843-522-5741 and notify Nursing Supervisor at 843-522-7653 ALL INFORMATION BELOW IS REQUIRED BY ORDERING PHYSICIAN Service Designation THIS IS NOT AN ADMISSION SET Patient Name ___________________________________ Patient DOB ____________ Service Designation Blood Platelet Outpatient Attending / Ordering Physician ______________________________ Date Requested ___________________________________ Status Outpatient Check Appropriate Diagnosis Below: [ Anemia of chronic renal disease Anemia related to chemotherapy Myelodysplasia Anemia related to cancer Anemia related to blood loss Sickle cell disease Anemia unspecified Thombocytopenia (platelets) Other _________________________ ] Allergies Update Allergies in the Summary Panel in MEDITECH Special Requirement: (REQUIRES SPECIAL ORDER ONE DAY IN ADVANCE) Special Requirement RBC or Platelets REQUIRES SPECIAL ORDER ONE DAY IN ADVANCE [ Irradiated CMV Negative HgBS Negative ] Vital Signs Per BMH Policy, Blood and Blood Component Administration, 07.02 Diet Mediterranean Style Diet 2 Gm Sodium Diet Regular 7 Diet 1800 kcal Consistent Carbohydrate Diet Other Dietper patient choice ____________________ Medications -

Platelet Transfusion in the Real Life

4 Editorial Commentary Page 1 of 4 Platelet transfusion in the real life Pilar Solves1,2 1Blood Bank, Hematology Service, Hospital Universitari I Politècnic la Fe, Valencia, Spain; 2CIBERONC, Instituto Carlos III, Madrid, Spain Correspondence to: Pilar Solves. Blood Bank, Hematology Unit, Hospital Universitari I Politècnic La Fe, Avda Abril Martorell, 106, Valencia 46026, Spain. Email: [email protected]. Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office,Annals of Blood. The article did not undergo external peer review. Comment on: Gottschall J, Wu Y, Triulzi D, et al. The epidemiology of platelet transfusions: an analysis of platelet use at 12 US hospitals. Transfusion 2020;60:46-53. Received: 06 April 2020. Accepted: 24 April 2020; Published: 30 June 2020. doi: 10.21037/aob-20-30 View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/aob-20-30 Platelet transfusion is a common practice in thrombocytopenic period, between January 2013 and December 2016. patients for preventing or treating hemorrhages. Platelets The results provide a general view on current platelet are mostly transfused to patients diagnosed of onco- transfusion practice in US. A total of 163,719 platelets hematological diseases and/or undergoing hematopoietic representing between 3% and 5% of all platelets stem cell transplantation (1). With the aim to help transfused in the country, were transfused into 31821 physicians to take the most accurate decisions on platelet patients of whom 60.5% were males. More than 60% of transfusion, some guidelines have been developed (2-6). platelets were from single donor apheresis and 72.5% The scientific evidence supporting the recommendations were irradiated. -

Crossmatching and Issuing Blood Components; Indications and Effects

CrossmatchingCrossmatching andand IssuingIssuing BloodBlood Components;Components; IndicationsIndications andand Effects.Effects. Alison Muir Blood Transfusion, Blood Sciences, Newcastle Trust TopicsTopics CoveredCovered • Taking the blood sample • ABO Group • Antibody Screening • Compatibility testing • Red cells • Platelets • Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP) • Cryoprecipitate • Other Products TakingTaking thethe BloodBlood SpecimenSpecimen Positively identify the patient Ask the patient to state their name and date of birth Inpatients - Look at the wristband for the Hospital Number and to confirm the name and date of birth are correct Outpatients – Take the hospital number from the notes or other documentation having confirmed the name and d.o.b. Take the blood specimen Label the tube AT THE BEDSIDE. the label must be hand-written The specimen bottle should be labelled with: First Name Surname Hospital number Date of Birth Ensure the Declaration is signed on the request form Taking blood from the wrong patient can lead to a fatal transfusion reaction RequestRequest FormForm Transfusion Sample Timings? Patients who have recently been transfused may form red cell antibodies. A new sample is required at the following times before any transfusion when: Patient Transfused or Sample required within Pregnant within the 72 hours before preceding 3 months: transfusion Uncertain or information Sample required within unavailable of transfusion or 72 hours before pregnancy: transfusion Patient NOT transfused or Sample valid for 3 pregnant within the months preceding 3 months: ABOABO GroupGroup TestingTesting •Single most important serological test performed on pre transfusion samples. Guidelines for pre –transfusion compatibility procedures •Sensitivity and security of testing systems must not be compromised. AntibodyAntibody ScreeningScreening • Antibody screening - the most reliable and sensitive method for the detection of red cell antibodies. -

Clinical Transfusion Practice

Clinical Transfusion Practice Guidelines for Medical Interns Foreword Blood transfusion is an important part of day‐to‐day clinical practice. Blood and blood products provide unique and life‐saving therapeutic benefits to patients. However, due to resource constraints, it is not always possible for the blood product to reach the patient at the right time. The major concern from the point of view of both user (recipient) and prescriber (clinician) is for safe, effective and quality blood to be available when required. Standard practices should be in place to include appropriate testing, careful selection of donors, screening of donations, compatibility testing, storage of donations for clinical use, issue of blood units for either routine or emergency use, appropriate use of blood supplied or the return of units not needed after issue, and reports of transfusion reactions – all are major aspects where standard practices need to be implemented. In order to implement guidelines for standard transfusion practices, a coordinated team effort by clinicians, blood transfusion experts, other laboratory personnel and health care providers involved in the transfusion chain, is needed. Orientation of standard practices is vital in addressing these issues to improve the quality of blood transfusion services. Bedside clinicians and medical interns are in the forefront of patient management. They are responsible for completing blood request forms, administering blood, monitoring transfusions and being vigilant for the signs and symptoms of adverse reactions. -

A Therapeutic Platelet Transfusion Strategy Is Safe and Feasible in Patients After Autologous Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation

Bone Marrow Transplantation (2006) 37, 387–392 & 2006 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0268-3369/06 $30.00 www.nature.com/bmt ORIGINAL ARTICLE A therapeutic platelet transfusion strategy is safe and feasible in patients after autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation H Wandt, K Schaefer-Eckart, M Frank, J Birkmann and M Wilhelm BMT-Unit, Hematology/Oncology, Klinikum Nu¨rnberg Nord, Nu¨rnberg, Germany Prophylactic platelet transfusions are considered as transmission of bacterial and viral infections, circulatory standard in most hematology centers, but there is a congestion, transfusion-related acute lung injury and long-standing controversy as to whether standard pro- alloimmunization. phylactic platelet transfusions are necessary or whether During the last 10 years, it has been clearly shown by this strategy could be replaced by a therapeutic transfu- several studies that severe thrombocytopenia after intensive sion strategy. In 106 consecutive cases of patients chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia can be safely receiving 140 autologous peripheral blood stem cell managed with a threshold of 10 Â 109/l or even lower for transplantations, we used a therapeutic platelet trans- routine prophylactic platelet transfusion.1–4 On the basis fusion protocol when patients were in a clinically of these results, three clinical studies were performed with stable condition. Platelet transfusions were only used a10Â 109/l trigger in recipients of high-dose chemo- when relevant bleeding occurred (more than petechial). therapy7total body irradiation (TBI), followed by hemato- Median duration of thrombocytopenia o20 Â 109/l and poietic stem cell support.5–7 All three studies proved the o10 Â 109/l was 6 and 3 days, which resulted in a total of safety of the 10 Â 109/l trigger for prophylactic platelet 989 and 508 days, respectively.