Samuel Johnson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Johnson*S Views on Women: from His Works

SAMUEL JOHNSON*S VIEWS ON WOMEN: FROM HIS WORKS by IRIS STACEY B.A., University of British .Columbia. 1946 A Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard The University of British Columbia September, 1963 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly ' purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives,. It is understood that copying, or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada. Date JjiMZ^kA- ^,/»^' ABSTRACT An examination of Samuel Johnson*s essays and his tragedy, Irene, and his Oriental tale, Rasselas, reveals that his concept of womanhood and his views on the education of woman and her role in society amount to a thorough-going criticism of the established views of eighteenth-century society. His views are in advance of those of his age. Johnson viewed the question of woman with that same practical good sense which he had brought to bear on literary criticism. It was important he said "to distinguish nature from custom: or that which is established because it was right, from that which is right only because it is established." Johnson thought that, so far as women were concerned, custom had dictated views and attitudes which reason denied. -

The Times and Influence of Samuel Johnson

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Martina Tesařová The Times and Influence of Samuel Johnson Bakalářská práce Studijní obor: Anglická filologie Vedoucí práce: Mgr. Ema Jelínková, Ph.D. OLOMOUC 2013 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma „Doba a vliv Samuela Johnsona“ vypracovala samostatně a uvedla úplný seznam použité a citované literatury. V Olomouci dne 15.srpna 2013 …………………………………….. podpis Poděkování Ráda bych poděkovala Mgr. Emě Jelínkové, Ph.D. za její stále přítomný humor, velkou trpělivost, vstřícnost, cenné rady, zapůjčenou literaturu a ochotu vždy pomoci. Rovněž děkuji svému manželovi, Joe Shermanovi, za podporu a jazykovou korekturu. Johnson, to be sure, has a roughness in his manner, but no man alive has a more tender heart. —James Boswell Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 2. The Age of Johnson: A Time of Reason and Good Manners ......................... 3 3. Samuel Johnson Himself ................................................................................. 5 3.1. Life and Health ......................................................................................... 5 3.2. Works ..................................................................................................... 10 3.3. Johnson’s Club ....................................................................................... 18 3.4. Opinions and Practice ............................................................................ -

The Canonical Johnson and Scott

11 THE CANONICAL JOHNSON AND SCOTT Both Dr. Johnson and Scott are pioneers in their respective fields. They have served as models for subsequent writers remarkably. They laid down literary principles of lasting worth. It is a must for every researcher to have a proper view of their canonical work. Born the son of a bookseller in Lichfield, Johnson was throughout his life prone to ill health. At the age of three he was taken to London to be ‘touched’ for scrofula. He entered Pembroke College, Oxford, in October 1728, and during his time there he translated into Latin Messiah, a collection of prayers and hymns by Alexander Pope, published in 1731. Johnson was an impoverished commoner and is said to have been hounded for his threadbare appearance; the customary title ‘Dr’ by which he is often known is the result of an honorary doctorate awarded him by the University in 1775. His father died in 1731, and left the family in penury; Johnson was a teacher at the grammar school in Market Bosworth during 1732, and then moved for three years to Birmingham, his first 12 essays appearing in the Birmingham Journal. There he completed his first book, A Voyage to Abyssinia (published 1735), a translation from the French version of the travels of Father Jerome Lobo, a Portuguese missionary. In 1735 he married Mrs. Elizabeth Porter (‘Tetty’), a widow 20 years his senior, and the couple harboured enduring affection for each other. They started a school at Edial, near Lichfield, but the project was unsuccessful, so they moved down to London in 1737, accompanied by one of their former pupils, David Garrick. -

The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D.," Appeared in 1791

•Y»] Y Y T 'Y Y Y Qtis>\% Wn^. ECLECTIC ENGLISH CLASSICS THE LIFE OF SAMUEL JOHNSON BY LORD MACAULAY . * - NEW YORK •:• CINCINNATI •:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK COMPANY Copvrigh' ',5, by American Book Company LIFE OF JOHNSOK. W. P. 2 n INTRODUCTION. Thomas Babington Macaulay, the most popular essayist of his time, was born at Leicestershire, Eng., in 1800. His father, of was a Zachary Macaulay, a friend and coworker Wilberforc^e, man "> f austere character, who was greatly shocked at his son's fondness ">r worldly literature. Macaulay's mother, however, ( encouraged his reading, and did much to foster m*? -erary tastes. " From the time that he was three," says Trevelyan in his stand- " read for the most r_ ard biography, Macaulay incessantly, part CO and a £2 lying on the rug before the fire, with his book on the ground piece of bread and butter in his hand." He early showed marks ^ of uncommon genius. When he was only seven, he took it into " —i his head to write a Compendium of Universal History." He could remember almost the exact phraseology of the books he " " rea'd, and had Scott's Marmion almost entirely by heart. His omnivorous reading and extraordinary memory bore ample fruit in the richness of allusion and brilliancy of illustration that marked " the literary style of his mature years. He could have written Sir " Charles Grandison from memory, and in 1849 he could repeat " more than half of Paradise Lost." In 1 81 8 Macaulay entered Trinity College, Cambridge. Here he in classics and but he had an invincible won prizes English ; distaste for mathematics. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

Samuel Johnson, Periodical Publication, and the Sentimental Reader: Virtue in Distress in the Rambler and the Idler Chance David Pahl

Document generated on 09/28/2021 4:02 p.m. Lumen Selected Proceedings from the Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies Travaux choisis de la Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle Samuel Johnson, Periodical Publication, and the Sentimental Reader: Virtue in Distress in The Rambler and The Idler Chance David Pahl Volume 36, 2017 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1037852ar DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1037852ar See table of contents Publisher(s) Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle ISSN 1209-3696 (print) 1927-8284 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Pahl, C. D. (2017). Samuel Johnson, Periodical Publication, and the Sentimental Reader: Virtue in Distress in The Rambler and The Idler. Lumen, 36, 21–35. https://doi.org/10.7202/1037852ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies / Société This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit canadienne d'étude du dix-huitième siècle, 2017 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Samuel Johnson, Periodical Publication, and the Sentimental Reader: Virtue in Distress in The Rambler and The Idler Chance David Pahl University of Ottawa Like many of the essay serials and magazines published in mid eigh- teenth-century England, Samuel Johnson’s Rambler (1750–52) and Idler (1758–60) contain numerous melancholy tales of “virtue in distress.” Young women who have lost health, wealth, or innocence reach out to Johnson’s eidolons for the reader’s benefit or their own relief. -

Spectators, Ramblers and Idlers: the Conflicted Nature of Indolence and the 18Th-Century Tradition of Idling

133 ARTICLES MONIKA FLUDERNIK Spectators, Ramblers and Idlers: The Conflicted Nature of Indolence and the 18th-Century Tradition of Idling The 18th century could be argued to present a threshold opening to a society of leisure. This insight is confirmed by a number of social developments and by a variety of discourses focusing both positively and negatively on the spread of leisure among an increasing segment of the population and the increased amount of available free time, its abuses and opportunities for self-improvement.1 More people from diverse social classes had the time to divert themselves at a variety of cultural and social events, and the range of available distractions and leisure activities also increased over the century. Many traditional sites of leisure, such as the theater or opera, opened themselves to a wider stratum of English society; others, like the amusement parks, were new creations that targeted a populace bent on self-improvement and entertainment in nearly equal measure.2 Among the discourses about these developments, early modern (Puritan) notions about the sinfulness3 of idleness and the necessity of constant labour remained promi- nent despite the increasing secularization of British society. Besides insights into the moral duties and values of work, such discourses frequently inflected their criticism of the laxity of current mores with class-related prejudices and preconceptions which indicated that leisure was perceived to be a privilege of the higher classes: […] There is one thing that more remarkably distinguishes Persons of Rank from the Commons, and that is our Natural Contempt of Business. Now the Vulgar, like a Hackney-Horse, never stir abroad without something to do; and they visit, like a Mer- chant upon Change, for their Profit more than their Pleasure. -

Course Guide Cover Page Template

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY CONTINUING EDUCATION INDEPENDENT & DISTANCE LEARNING British Literature I: The Middle Ages, Renaissance, and 18th Century ENGLISH 3020 British Literature I: The Middle Ages, Renaissance, and 18th Century. Survey of English literature from the Anglo-Saxon period through Chaucer, Shakespeare, the 17th and 18th centuries. ENGL 3020 15 lessons and 3 exams. 3 hours of college credit. 08/11/04. version R Prerequisite: The satisfactory completion of English 1002, 1003, 1005, or equivalent credit is prerequisite for all English courses numbered 2001 or higher. ENGLISH 3020 British Literature I: The Middle Ages, Renaissance, and 18th Century Copyright © 2004 LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY BATON ROUGE, LOUISIANA Dorothy McCaughey, MA Instructor in English Independent & Distance Learning Louisiana State University All rights reserved. No part of this course guide may be used or reproduced without written permission of LSU Independent & Distance Learning. Printed in the United States of America. LB Table of Contents TTaabbllee ooff CCoonntteennttss How to Take an Independent Learning Course ......................................................................... iii Where the Books Are ............................................................................................................................. vii Syllabus ....................................................................................................................................................... S–1 Textbooks Other Materials Nature and Purpose of -

Anatomy of Criticism with a New Foreword by Harold Bloom ANATOMY of CRITICISM

Anatomy of Criticism With a new foreword by Harold Bloom ANATOMY OF CRITICISM Four Essays Anatomy of Criticism FOUR ESSAYS With a Foreword by Harold Bloom NORTHROP FRYE PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY Copyright © 1957, by Princeton University Press All Rights Reserved L.C. Card No. 56-8380 ISBN 0-691-06999-9 (paperback edn.) ISBN 0-691-06004-5 (hardcover edn.) Fifteenth printing, with a new Foreword, 2000 Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Council of the Humanities, Princeton University, and the Class of 1932 Lectureship. FIRST PRINCETON PAPERBACK Edition, 1971 Third printing, 1973 Tenth printing, 1990 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) {Permanence of Paper) www.pup.princeton.edu 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 Printed in the United States of America HELENAE UXORI Foreword NORTHROP FRYE IN RETROSPECT The publication of Northrop Frye's Notebooks troubled some of his old admirers, myself included. One unfortunate passage gave us Frye's affirmation that he alone, of all modern critics, possessed genius. I think of Kenneth Burke and of William Empson; were they less gifted than Frye? Or were George Wilson Knight or Ernst Robert Curtius less original and creative than the Canadian master? And yet I share Frye's sympathy for what our current "cultural" polemicists dismiss as the "romantic ideology of genius." In that supposed ideology, there is a transcendental realm, but we are alienated from it. -

ENL 3XXX the Long Eighteenth Century: Themes and Interpretation

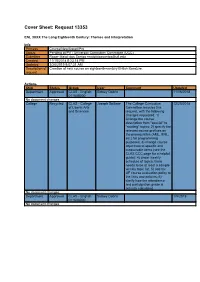

Cover Sheet: Request 13353 ENL 3XXX The Long Eighteenth Century: Themes and Interpretation Info Process Course|New|Ugrad/Pro Status Pending at PV - University Curriculum Committee (UCC) Submitter Roger Maioli dos Santos [email protected] Created 11/15/2018 5:23:14 PM Updated 3/26/2019 9:07:31 AM Description of Creation of new course on eighteenth-century British literature. request Actions Step Status Group User Comment Updated Department Approved CLAS - English Sidney Dobrin 11/16/2018 011608000 No document changes College Recycled CLAS - College Joseph Spillane The College Curriculum 12/20/2018 of Liberal Arts Committee recycles this and Sciences request, with the following changes requested: 1) Change the course description from "special" to "rotating" topics; 2) specify the relevant course prefixes on the prerequisites (AML, ENL, etc.) for programming purposes; 3) change course objectives to specific and measurable items (see the CLAS CCC page for a helpful guide); 4) under weekly schedule of topics, there needs to be at least a sample weekly topic list; 5) add the UF course evaluation policy to the links and policies; 6) clarify how the attendance and participation grade is actually calculated. No document changes Department Approved CLAS - English Sidney Dobrin 1/5/2019 011608000 No document changes Step Status Group User Comment Updated College ConditionallyCLAS - College Joseph Spillane The Committee conditionally 2/8/2019 Approved of Liberal Arts approves this request, with and Sciences the following changes needed: 1) -

Teaching Life As Story

THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF LIFE WRITING VOLUME VII(2018)TL15–TL28 Teaching Life as Story Jane McVeigh University of Roehampton and Oxford University Department for Continuing Education The way that people tell their life story, and are supported to do so, can be empowering and open up new opportunities. Following a long career working in community based not-for-profit organisations, my research and teaching has always been underpinned by the belief that one way to under- stand day-to-day lives is through stories. Listening to and reading about the lives of other people, as well as narrating our own lives, is part of every- day life. Reading, writing about, watching and listening to narrative dis- course in different forms, and writing about people’s lives in creative and re-creative writing — and I include metanarratives in the latter—are just a few of the ways that help us grapple with the lives of ourselves and others. Whether we then go on to understand people any better is a different story and is influenced by our own place in the world and the way that the story is framed by ourselves or others within historical, cultural, social and politi- cal contexts, as recent theory has taught us. Also, my own research on the changing nature of archives and concerns about authenticity in public dis- course and the fluidity of genre, as well as my background in literary criti- cism, have undoubtedly influenced the design and content of my teaching. As biographer Claire Tomalin comments, “What you look for when you are thinking about a biography are the stories in somebody’s life” (2004, 92). -

Johnson and Slavery

Johnson and slavery The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Basker, James G. 2011. Johnson and slavery. Harvard Library Bulletin 20 (3-4), Fall-Winter 2009: 29-50. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42668888 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Johnson and Slavery James G. Basker uring a sabbatical year in 1993–94, I noticed for the frst time a strange footnote in the frst edition of Boswell’s Life of Johnson (1791) that Dpiqued my interest in the question of Johnson and slavery.1 When I discussed it with Walter Jackson Bate a few weeks later, he ofered energetic encouragement, which helped decide me to pursue the subject in depth.2 A few essays followed and evolved into a book-length project on which I am now working, under the title Samuel Johnson, Abolitionist: Te Story Boswell Never Told.3 Te rationale for that subtitle will become self-evident, I hope, in the course of this essay. I propose to illuminate selected moments in Johnson’s lifelong opposition to slavery, particularly those that are minimized or missing altogether in Boswell’s Life of Johnson. Ultimately, I want to ofer a new angle of vision on Johnson, one that does a couple of things for us as students of his life and work.