SLACK BAY Press Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SMALL CRIMES DIAS News from PLANET MARS ALL of a SUDDEN

2016 IN CannES NEW ANNOUNCEMENTS UPCOMING ALSO AVAILABLE CONTACT IN CANNES NEW Slack BAY SMALL CRIMES CALL ME BY YOUR NAME NEWS FROM NEW OFFICE by Bruno Dumont by E.L. Katz by Luca Guadagnino planet mars th Official Selection – In Competition In Pre Production In Pre Production by Dominik Moll 84 RUE D’ANTIBES, 4 FLOOR 06400 CANNES - FRANCE THE SALESMAN DIAS NEW MR. STEIN GOES ONLINE ALL OF A SUDDEN EMILIE GEORGES (May 10th - 22nd) by Asghar Farhadi by Jonathan English by Stephane Robelin by Asli Özge Official Selection – In Competition In Pre Production In Pre Production [email protected] / +33 6 62 08 83 43 TANJA MEISSNER (May 11th - 22nd) GIRL ASLEEP THE MIDWIFE [email protected] / +33 6 22 92 48 31 by Martin Provost by Rosemary Myers AN ArtsCOPE FILM NICHolas Kaiser (May 10th - 22nd) In Production [email protected] / +33 6 43 44 48 99 BERLIN SYNDROME MatHIEU DelaUNAY (May 10th - 22nd) by Cate Shortland [email protected] / + 33 6 87 88 45 26 In Post Production Sata CissokHO (May 10th - 22nd) [email protected] / +33 6 17 70 35 82 THE DARKNESS design: www.clade.fr / Graphic non contractual Credits by Daniel Castro Zimbrón Naima ABED (May 12th - 20th) OFFICE IN PARIS MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL In Post Production [email protected] / +44 7731 611 461 9 Cité Paradis – 75010 Paris – France Tel: +33 1 53 34 90 20 | Fax: +33 1 42 47 11 24 [email protected] [email protected] Proudly sponsored by www.memento-films.com | Follow us on Facebook NEW OFFICE IN CANNES 84 RUE D’ANTIBES, 4th FLOOR -

Charles Péguy

Joan of Arc A film by BRUNO DUMONT Synopsis In the 15th century, both France and England stake a blood claim for the French throne. Believing that God had chosen her, the young Joan leads the army of the King of France. When she is captured, the Church sends her for trial on charges of heresy. Refusing to accept the accusations, the graceful Joan of Arc will stay true to her mission. Bruno Dumont’s decision to work with a ten-year-old actress re-injects this heroine’s timeless cause and ideology with a modernity that highlights both the tragic female condition and the incredible fervor, strength and freedom women show when shackled by societies and archaic virile orders that belittle and alienate them. ©3B Productions Cast Lise Leplat Prudhomme, Jean-François Causeret, Daniel Dienne, Fabien Fenet, Robert Hanicotte, Yves Habert. With the kind participation of Fabrice Luchini and Christophe. Crew Director & Screenwriter: Bruno Dumont Make Up: Simon Livet Based on novels by Charles Péguy Hair: Clément Douel Music Composer: Christophe Costume Design: Alexandra Charles Producers: Jean Bréhat, Rachid Bouchareb, Set Designer: Erwan Legal Muriel Merlin Location Manager: Edouard Sueur Line Producer: Cédric Ettouati Still Photographer: Roger Arpajou Cinematographer: David Chambille Script Supervisor: Virginie Barbay A 3B Productions. With the participation of Sound: Philippe Lecœur Pictanovo and the support of La Région Hauts Mixing: Emmanuel Croset de France with the participation of the Centre Sound Editor: Romain Ozanne National du Cinéma et de l’Image Animée. In Editors: Bruno Dumont and Basile Belkhiri association with CINECAP 2. First Assistant: Rémi Bouvier World Sales: Luxbox Casting: Clément Morelle French Distribution: Les Films du Losange Dialogue Coach: Julie Sokolowski ©3B Productions 2019, 138 minutes, France, Color 1.85 - 5.1 – French AN INTERVIEW WITH THE DIRECTOR Bruno Dumont Joan is the sequel to Jeannette and the two films form the Péguy wrote a text that was precise in the field of ideas and very lyrical adaptation of a play by Charles Péguy. -

Contacts in Berlin

2016 SCREENING IN BERLIN NEW PROJECTS UPCOMING STILL AVAILABLE CONTACTS IN BERLIN - EFM NEWS FROM MR. STEIN GOES ONLINE BERLIN SYNDROME A MONSTER MARTIN GROPIUS BAU – BOOTH #33 planet mars by Stephane Robelin by Cate Shortland WITH A THOUSAND th th by Dominik Moll In Pre-production In Post-Production HEADS EMILIE GEORGES (February 10 – 17 ) [email protected] / +33 6 62 08 83 43 Official Selection – SCRIPT AVAILABLE NEW PROMOREEL by Rodrigo Plá th th Out of Competition THE MIDWIFE SlacK BAY TANJA MEISSNER (February 10 – 18 ) [email protected] / +33 6 22 92 48 31 ALL OF A SUDDEN by Martin Provost by Bruno Dumont NEON BULL by Gabriel Mascaro th th by Asli Özge In Pre-production In Post-Production Nicholas KAISER (February 10 – 18 ) Panorama Special SCRIPT AVAILABLE NEW PROMOREEL [email protected] / +33 6 43 44 48 99 NEW Mathieu DelaunaY (February 10th – 18th) ASGHAR FARHADI’S THE DARKNESS [email protected] / +33 6 87 88 45 26 by Daniel Castro Zimbrón GIRL ASLEEP UNTITLED PROJECT Sata Cissokho (February 12th – 18th) by Rosemary Myers by Asghar Farhadi In Post-Production [email protected] / +33 6 17 70 35 82 Generation 14Plus – Opening Film In Post-Production TEASER AVAILABLE th th NEW SCRIPT AVAILABLE Naima Abed (February 10 – 16 ) AN Artscope FILM [email protected] / +44 7 731 611 461 OFFICE IN PARIS MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL 9 Cité Paradis – 75010 Paris – France | Tel: +33 1 53 34 90 20 Fax: +33 1 42 47 11 24 | [email protected] | [email protected] | www.memento-films.com |Follow -

Line up Brochure Cannes 2017 New.Indd

attending may 17th - 25th - rIvIera J8 fIOrella mOrettI I fi orella@luxboxfi lms.com I +33 6 26 10 07 65 héDI ZarDI I hedi@luxboxfi lms.com I +33 6 64 46 10 11 aNNe SOPhIe trINtIgNaC I festivals@luxboxfi lms.com I +33 7 63 42 26 12 A CIAMBRA A film by JONaS CarPIgNaNO “ By the director of Mediterranea (Cannes Critics’ Week 2015), Best Director at the Gotham Independent Film Awards and 3 nominations at the Film Independent Spirit Awards including Best First Feature. Winner of the Cannes Discovery Award with his short film A Ciambra in 2014 (Cannes Critics’ Week 2014). His second feature A Ciambra, based on his short film, was developed at the Cannes Cinéfondation Residence » 2017 I 120 min I Italian I Drama Italy, US, France, Sweden CAST: Pio Amato, Koudous Seihon, Iolanda Amato, Damiano Amato PRODUCTION: Stayblack Productions, RT Features, Sikelia Productions, Rai Cinema SYNOPSIS: In A CIAMBRA, a small Romani community in Calabria, Pio Amato is desperate to grow up fast. At 14, he drinks, smokes and is one of the few to easily slide between the regions’ factions - the local Italians, the African immigrants and his fellow Romani. Pio follows his older brother Cosimo everywhere, learning the necessary skills for life on the streets of their hometown. When Cosimo disappears and things start to go wrong, Pio sets out to prove he’s ready to step into his big brother’s shoes and in the process he must decide if he is truly ready to become a man. A CIAMBRA Available worldwide. -

6490 Gott & Kealhofer-Kemp.Indd

ReFocus: The Films of Rachid Bouchareb 66490_Gott490_Gott & KKealhofer-Kemp.inddealhofer-Kemp.indd i 111/09/201/09/20 77:03:03 PPMM ReFocus: The International Directors Series Series Editors: Robert Singer, Stefanie Van de Peer, and Gary D. Rhodes Board of Advisors: Lizelle Bisschoff (University of Glasgow) Stephanie Hemelryck Donald (University of Lincoln) Anna Misiak (Falmouth University) Des O’Rawe (Queen’s University Belfast) ReFocus is a series of contemporary methodological and theoretical approaches to the interdisciplinary analyses and interpretations of international film directors, from the celebrated to the ignored, in direct relationship to their respective culture—its myths, values, and historical precepts—and the broader parameters of international film history and theory. The series provides a forum for introducing a broad spectrum of directors, working in and establishing movements, trends, cycles, and genres including those historical, currently popular, or emergent, and in need of critical assessment or reassessment. It ignores no director who created a historical space—either in or outside of the studio system—beginning with the origins of cinema and up to the present. ReFocus brings these film directors to a new audience of scholars and general readers of Film Studies. Titles in the series include: ReFocus: The Films of Susanne Bier Edited by Missy Molloy, Mimi Nielsen, and Meryl Shriver-Rice ReFocus: The Films of Francis Veber Keith Corson ReFocus: The Films of Jia Zhangke Maureen Turim and Ying Xiao ReFocus: The -

COINCOIN and the EXTRA-HUMANS (Coincoin Et Les Z’Inhumains) by Bruno Dumont

COINCOIN AND THE EXTRA-HUMANS (CoinCoin et les z’inhumains) by Bruno Dumont 208 min (4 episodes approx. 52 min), Colour 2.35.1 - French with English subtitles/France 2018/ World Premiere Locarno Film Festival 2018 Online release Summer 2020 date tbc FOR ALL PRESS ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Sue Porter/Lizzie Frith – Porter Frith Ltd Tel. 07940 584066/07825 603705 [email protected] FOR ALL OTHER ENQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT Robert Beeson – [email protected] Dena Blakeman – [email protected] Unit 9, Bickels Yard 151 – 153 Bermondsey Street London SE1 3HA [email protected] SYNOPSIS: In this follow up to P’tit Quinquin, Quinquin is now grown up and goes by the nickname Coincoin. He hangs out, doing little and does some security for meetings with his childhood friend Fatso of the Nationalist Party. His old love, Eve, has abandoned him for Corinne. When a strange magma resembling a large cow-pat is found near the town, the inhabitants suddenly start to behave very weirdly. Captain Van Der Weyden and his loyal assistant Carpentier investigate these alien attacks, which result in those infected giving birth to their own double. The Extra-Human invasion has begun. Episode 1 Black be Black Episode 2 The Extra-Humans Episode 3 Gunk, Gunk, Gunk!!! Episode 4 The Apocalypse High Res stills here Further information and downloads here CAST Coincoin ALANE DELHAYE Roger van der Weyden BERNARD PRUVOST Rudy Carpentier PHILIPPE JORE Fatso JULIEN JORE Maurice Leleu CHRISTOPHE VERHEECK Jenny ALEXIA DEPRET Eve Terrier LUCY CARON Mrs Leleu -

Bruno Dumont - Biography

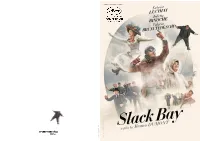

Jean BREHAT Rachid BOUCHARE B & Muriel MERLIN present Fabrice LUCHINI Juliette BINOCHE Valeria BRUNI TEDESCHI Photo : R.Arpajou © 3B s TROÏKA Slack Bay a film by Bruno DUMONT © photos : RogerARPAJOU © 3B Design : Laurent Pons / Jean BREHAT Rachid BOUCHAREB & Muriel MERLIN present OFFICIAL SELECTION CANNES FESTIVAL Fabrice LUCHINI Juliette E BINOCH Valeria DESCHI BRUNI TE DUMONT Slack Bruno Bay a film by www.slackbay.com 122 min - colour - Scope - 5.1 - France / Germany World Sales & Festivals International Press WOLF consultants Gordon Spragg, Laurin Dietrich, t : +33 1 53 34 90 20 Michael Arnon sales@memento-films.com t : +49 157 7474 9724 festival@memento-films.com [email protected] http://international.memento-films.com/ www.wolf-con.com SYNOPSIS Summer 1910. Several tourists have vanished while relaxing on the beautiful beaches of Towering high above the bay stands the van Peteghems’ mansion. Every summer, this the Channel Coast. Infamous inspectors Machin and Malfoy soon gather that the epicenter bourgeois family – all degenerate and decadent from inbreeding – stagnates in the villa, of these mysterious disappearances must be Slack Bay, a unique site where the Slack river not without mingling during their leisure hours of walking, sailing or bathing, with the and the sea join only at high tide. ordinary local people, Ma Loute and the other Bruforts. There lives a small community of fishermen and other oyster farmers. Among them evolves Over the course of five days, as starts a peculiar love story between Ma Loute and the a curious family, the Brufort, renowned ferrymen of the Slack Bay, lead by the father nick- young and mischievous Billie van Peteghem, confusion and mystification will descend on named “The Eternal”, who rules as best as he can on his prankster bunch of sons, especially both families, shaking their convictions, foundations and way of life. -

Hollywood Reporter

'Jeanette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc': Film Review | Cannes 2017 http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/print/1000848 Source URL: http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/jeanette-childhood-joan-arc-review-1000848 'Jeanette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc': Film Review | Cannes 2017 1:30 AM PDT 5/21/2017 by Jordan Mintzer Courtesy of Cannes Directors’ Fortnight The Bottom Line Joan of Arc Superstar. French auteur Bruno Dumont (‘Humanite,’ ‘Slack Bay’) directed this song-and-dance take on the story of Joan of Arc’s spiritual awakening. Love them or hate them, the films of Bruno Dumont never cease to confound. For a long time the 59-year-old auteur was known for his uncompromising — and uncompromisingly bleak — early works like The Life of Jesus and Humanite , which featured amateur actors and were set in the darkest corners of northern France. Then the director switched gears about five years ago with the Juliette Binoche-starrer Camille Claudel 1915 , following that up with the surprisingly hilarious TV miniseries, Lil’ Quinquin . After another stab at comedy with Slack Bay , which played in competition last year, Dumont is back at the Cannes Directors’ Fortnight with an attempt at, well, musical comedy in the bizarre yet often exhilarating spiritual Jeanette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc ( Jeanette, l’enfance de Jeanne d’Arc ). Imagine a high school stage production set in the 15th century and featuring an electro-rock score that’s equal parts Meatloaf, Skrillex and Cannibal Corpse (with a bit of French hip-hop thrown in for kicks) — all of it captured by Dumont’s impeccable filmmaking acumen, with regular DP Guillaume Deffontaines doing another impressive job behind the camera — and you can get a vague idea of what’s in store. -

Louder Than Bombs the Propaganda

2015 IN CANNES NEW UPCOMING STILL AVAILABLE CONTACT IN CANNES LOUDER SLACK BAY BERLIN BODY th th THAN BOMBS by Bruno Dumont SYNDROME by Malgorzata Szumowska EMILIE GEORGES (May 13 -24 ) [email protected] / +33 6 62 08 83 43 th th by Joachim Trier In Pre-Production by Cate Shortland TANJA MEISSNER (May 13 -24 ) [email protected] / +33 6 22 92 48 31 COP CAR th th In Competiton In Pre-Production NICHolas Kaiser (May 13 -24 ) [email protected] / +33 6 43 44 48 99 by Jon Watts THE DARKNESS MatHIEU DelaUNAY (May 13th -24th) [email protected] / + 33 6 87 88 45 26 by Daniel Castro Zimbrón THE PROPAGANDA NEWS FROM th th GAME In Production Sata CissokHO (May 13 -24 ) [email protected] / +33 6 17 70 35 82 PLANET MARS Naima ABED (May 13th -24th) [email protected] / +44 7731 611 461 by Alvaro Longoria by Dominik Moll World Market Premiere In Production OFFICE IN CANNES JAMES WHITE MARGUERITE RD by Josh Mond by Xavier Giannoli 25 Croisette, Bagatelle, 3 FLOOR World Market Premiere In Post-Production 06400 CANNES – FRANCE Graphic design: www.clade.fr / Credits non contractual / Credits design: www.clade.fr Graphic OFFICE IN PARIS MEMENTO FILMS INTERNATIONAL | 9 Cité Paradis – 75010 Paris – France | Tel: +33 1 53 34 90 20 | Fax: +33 1 42 47 11 24 [email protected] | [email protected] | international.memento-films.com |Follow us on Facebook Proudly sponsored by LOUDER THAN BOMBS JOACHIM TRIER By the director of Oslo, August 31st (Cannes 2011 – Un Certain Regard) and Reprise in Cannes LOUDER THAN -

Fokus Cannes Focus on Cannes Aktuelles & Szene News & Scene

Fokus Cannes Aktuelles & Szene Produktionsnotizen Focus on Cannes News & Scene Production Notes 02/2016 bilingual TRAILER edition Infomagazin der Mitteldeutschen Medienförderung GmbH TRAILER 02/2016 INHALT CONTENT 3 INHALT 02/2016 CONTENT 02/2016 LIEBE LESERINNEN UND LESER, DEAR READER, auch bei den 69. Internationalen Filmfestspielen Cannes ist die Once again this year, at the 69th International Film Festival of MDM mit einem geförderten Projekt vertreten: „Ma Loute“, Cannes, MDM is part of the action with a funded film: “Slack Bay” die neue Regiearbeit des französischen Autorenfilmers Bruno is competing for the Golden Palm; it is the latest directing work of Dumont, der mit seinen Werken regelmäßig für Diskussionsstoff French auteur-filmmaker Bruno Dumont, whose films are routinely sorgt, geht im Wettbewerb ins Rennen um die Goldene Palme. the subject of controversy. Another star of European arthouse Eine weitere Größe des europäischen Arthouse-Kinos kehrte cinema recently returned to our region of Mitteldeutschland: “Irina kürzlich nach Mitteldeutschland zurück: Noch bis Mitte Mai dreht Palm” director Sam Garbarski is shooting parts of his historical „Irina Palm“-Regisseur Sam Garbarski in Sachsen, Sachsen-Anhalt comedy with the working title “Auf Wiedersehen Deutschland” in und Thüringen Teile seiner historischen Komödie „Auf Wieder- the states of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Thuringia. And that’s just sehen Deutschland“ (AT). Daneben fanden in den vergangenen one of many exciting projects shot in our region over the past few Wochen weitere spannende Dreharbeiten in der Region statt. weeks. You can read about all of those in the “Trailer” edition you Auch über diese Projekte lesen Sie in der vorliegenden Ausgabe. -

Charles Péguy

SYNOPSIS France, 1425. In the midst of the Hundred Years’ War, the young Jeannette, at the still tender age of 8, looks after her sheep in the small village of Domremy. One day, she tells her friend Hauviette how she cannot bear to see the suffe- ring caused by the English. Madame Gervaise, a nun, tries to reason with the young girl, but Jeannette is ready to take up arms for the salvation of souls and the liberation of the Kingdom of France. Carried by her faith, she will become Joan of Arc. JEANNETTE, THE CHILDHOOD OF JOAN OF ARC A musical film by Bruno Dumont 2017, 106 min, format 1.55 ,Colour, France Photos: Roger Arpajou and David Koskas CAST Lise Leplat Prudhomme, Jeanne Voisin, Lucile Gauthier, Victoria Lefebvre, Aline Charles, Elise Charles, Nicolas Leclaire, Gery De Poorter, Regine Delalin, Anaïs Rivière CREW Director & Screenwriter: Bruno Dumont Costum Design: Alexandra Charles Based on novels by Charles Péguy Hair And Make Up: Simon Livet Music composer : IGORRR Casting: Clément Morelle Additional music composers : Nils First Assistant: Claude Guillouard Cheville, Laure Le Prunenec, Aline Dialogs Director: Catherine Charrier Charles, Elise Charles, Anaïs Rivière Songs Director: Laure Le Prunenec Choreographer : Philippe Decouflé Location Manager: Edouard Sueur assisted by Clémence Galliard Additionnal Choreographers : Aline Producers: Jean Bréhat, Rachid Charles, Elise Charles, Nicolas Leclaire Bouchareb, Muriel Merlin Victoria Lefebvre, Jeanne Voisin A Taos Films - Arte France coproduction Cinematographer : Guillaume with -

Katalóg Catalogue 2018

15.—23. 15.—23. JÚN 2018 JÚN 2018 KATALÓG CATALOGUE ISBN 978 – 80 – 972310 – 2 – 6 POĎAKOVANIE SPECIAL THANKS TO Festival sa koná pod záštitou predsedu vlády Slovenskej republiky Petra Pellegriniho. The festival is held under the auspices of Prime Minister of the Slovak Republic Peter Pellegrini. Festival finančne podporil With the financial support of Toto podujatie sa realizuje vďaka podpore Košického samosprávneho kraja. This event is made possible by the support of the Košice Self-governing Region. 4 POĎAKOVANIE SPECIAL THANKS TO Andrea Baisová Mátyás Prikler Anne-Sophie Lehec Mayo Hurajt Bastian Meiresonne Mayo Hirc Dagmar Krepoppová Milan Jursa Daniel Franko Miroslava Grimaldi Denisa Biermannová Nancy Fornoville Donsaron Kovitvanitcha Nils S. Edlund Eduard Weiss Olga Kovářová Eva Križková Ondřej Beck Ivan Hronec Otto Reiter Ján Herda Panos Kotzathanasis Ján Kováč Peter Dubecký Jana Studená Peter Kerekes Josefina Mothander Peter Kot Jozef Valachovič Peter Michalovič Karim Mezoughi Peter Neveďal Lenka Vargová Jurková Peter Novák Ľuba Féglová Peter Radkoff Ľubica Orechovská Radovan Holub Lucia Gertli Rastislav Trnka Lukáš Berberich Richard Herrgott Margaréta Gregáňová Rudolf Biermann Marián Hausner Soňa Macejková Marian Urban Štefánia Matejová Marieta Širáková Veronika Paštéková Martin Dani Wanda Adamík Hrycová Martin Šmatlák Zuzana Hadravová Martina Mlichová Zuzana Štefunková Martina Paštéková Nice Looking People of NAFFE 5 ZÁMER STATEMENT OF PURPOSE Zámer Statement of Purpose Dôležitým zámerom Art Film Festu je predstaviť výber Art