Northern Goshawk, Accipiter Gentilis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LONG-EARED OWL INSIDE by CHRIS NERI and NOVA MACKENTLEY News from the Board and Staff

WINTER 2014 TAKING FLIGHT NEWSLETTER OF HAWK RIDGE BIRD OBSERVATORY The elusive Long-eared Owl Photo by Chris Neri THE LONG-EARED OWL INSIDE by CHRIS NERI and NOVA MACKENTLEY News from the Board and Staff..... 2 For many birders thoughts of Long-eared Owls invoke memories of winter Education Updates .................. 4 visits to pine stands in search of this often elusive species. It really is magical Research Features................... 6 to enter a pine stand, find whitewash and pellets at the base of trees and realize that Long-eareds are using the area that you are searching. You scan Stewardship Notes ................. 12 up the trees examining any dark spot, usually finding it’s just a tangle of Volunteer Voices.................... 13 branches or a cluster of pine needles, until suddenly your gaze is met by a Hawk Ridge Membership........... 14 pair of yellow eyes staring back at you from a body cryptically colored and Snore Outdoors for HRBO ......... 15 stretched long and thin. This is often a birders first experience with Long- eared Owls. However, if you are one of those that have journeyed to Hawk Ridge at night for one of their evening owl programs, perhaps you were fortunate enough to see one of these beautiful owls up close. CONTINUED ON PAGE 3 HAWK RIDGE BIRD OBSERVATORY 1 NOTES FROM THE DIRECTOR BOARD OF DIRECTORS by JANELLE LONG, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR As I look back to all of the accomplishments of this organization, I can’t help but feel proud CHAIR for Hawk Ridge Bird Observatory and to be a part of it. -

A Multi-Gene Phylogeny of Aquiline Eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) Reveals Extensive Paraphyly at the Genus Level

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com MOLECULAR SCIENCE•NCE /W\/Q^DIRI DIRECT® PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION ELSEVIER Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 35 (2005) 147-164 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A multi-gene phylogeny of aquiline eagles (Aves: Accipitriformes) reveals extensive paraphyly at the genus level Andreas J. Helbig'^*, Annett Kocum'^, Ingrid Seibold^, Michael J. Braun^ '^ Institute of Zoology, University of Greifswald, Vogelwarte Hiddensee, D-18565 Kloster, Germany Department of Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD 20746, USA Received 19 March 2004; revised 21 September 2004 Available online 24 December 2004 Abstract The phylogeny of the tribe Aquilini (eagles with fully feathered tarsi) was investigated using 4.2 kb of DNA sequence of one mito- chondrial (cyt b) and three nuclear loci (RAG-1 coding region, LDH intron 3, and adenylate-kinase intron 5). Phylogenetic signal was highly congruent and complementary between mtDNA and nuclear genes. In addition to single-nucleotide variation, shared deletions in nuclear introns supported one basal and two peripheral clades within the Aquilini. Monophyly of the Aquilini relative to other birds of prey was confirmed. However, all polytypic genera within the tribe, Spizaetus, Aquila, Hieraaetus, turned out to be non-monophyletic. Old World Spizaetus and Stephanoaetus together appear to be the sister group of the rest of the Aquilini. Spiza- stur melanoleucus and Oroaetus isidori axe nested among the New World Spizaetus species and should be merged with that genus. The Old World 'Spizaetus' species should be assigned to the genus Nisaetus (Hodgson, 1836). The sister species of the two spotted eagles (Aquila clanga and Aquila pomarina) is the African Long-crested Eagle (Lophaetus occipitalis). -

Accipiters.Pdf

Accipiters The northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and the sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter striatus) are the Alaskan representatives of a group of hawks known as accipiters, with short, rounded wings (short in comparison with other hawks) and long tails. The third North American accipiter, the Cooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii) is not found in Alaska. Both native species are abundant in the state but not commonly seen, for they spend the majority of their time in wooded habitats. When they do venture out into the open, the accipiters can be recognized easily by their “several flaps and a glide” style of flight. General Description: Adult northern goshawks are bluish- gray on the back, wings, and tail, and pearly gray on the breast and underparts. The dark gray cap is accented by a light gray stripe above the red eye. Like most birds of prey, female goshawks are larger than males. A typical female is 25 inches (65 cm) long, has a wingspread of 45 inches (115 cm) and weighs 2¼ pounds (1020 g) while the average male is 19½ inches (50 cm) in length with a wingspread of 39 inches (100 cm) and weighs 2 pounds (880 g). Adult sharp-shinned hawks have gray backs, wings and tails (males tend to be bluish-gray, while females are browner) with white underparts barred heavily with brownish-orange. They also have red eyes but, unlike goshawks, have no eyestrip. A typical female weighs 6 ounces (170 g), is 13½ inches (35 cm) long with a wingspread of 25 inches (65 cm), while the average male weighs 3½ ounces (100 g), is 10 inches (25 cm) long and has a wingspread of 21 inches (55 cm). -

Our Recent Bird Surveys

Breeding Birds Survey at Germantown MetroPark Scientific Name Common Name Scientific Name Common Name Accipiter cooperii hawk, Cooper's Corvus brachyrhynchos crow, American Accipiter striatus hawk, sharp shinned Cyanocitta cristata jay, blue Aegolius acadicus owl, saw-whet Dendroica cerulea warbler, cerulean Agelaius phoeniceus blackbird, red-winged Dendroica coronata warbler, yellow-rumped Aix sponsa duck, wood Dendroica discolor warbler, prairie Ammodramus henslowii sparrow, Henslow's Dendroica dominica warbler, yellow-throated Ammodramus savannarum sparrow, grasshopper Dendroica petechia warbler, yellow Anas acuta pintail, northern Dendroica pinus warbler, pine Anas crecca teal, green-winged Dendroica virens warbler, black-throated Anas platyrhynchos duck, mallard green Archilochus colubris hummingbird, ruby-throated Dolichonyx oryzivorus Bobolink Ardea herodias heron, great blue Dryocopus pileatus woodpecker, pileated Asio flammeus owl, short-eared Dumetella carolinensis catbird, grey Asio otus owl, long-eared Empidonax minimus flycatcher, least Aythya collaris duck, ring-necked Empidonax traillii flycatcher, willow Baeolphus bicolor titmouse, tufted Empidonax virescens flycatcher, Acadian Bombycilla garrulus waxwing, cedar Eremophia alpestris lark, horned Branta canadensis goose, Canada Falco sparverius kestrel, American Bubo virginianus owl, great horned Geothlypis trichas yellowthroat, common Buteo jamaicensis hawk, red-tailed Grus canadensis crane, sandhill Buteo lineatus hawk, red-shouldered Helmitheros vermivorus warbler, worm-eating -

Red Tailed Hawk

FACT SHEET Red-Tailed Hawk COOL FACTS: Scientifi c name: Buteo jamaicensis Average weight: female: 31-51ounces; male: 25-45 ounces Average length: female: 19-25 inches; male: 17-22 inches Average wing span: 44-52 inches both sexes (3.5- 4.5 feet) Did you know? Most common hawk in North America. PHYSIOLOGY This is one of the largest birds you will see in North America. Even though the female of the species is larger than the male, the biggest female’s weight is only about 3 pounds. The oldest know Red-Tailed Hawk was 28 years and 10 months old. This species is blocky and broad in shape. A whitish underbelly with a dark brown band formed by horizontal streaks in feather patterning is present in most colour variations. The red tail, which gives this species its name, is uniformly brick-red above and light buff-orange below. The beak is short and dark and in the hooked, raptor shape. The head can sometimes appear small in size against the thick body frame. They have relatively short, broad tails and thick, chunky wings. The legs and the feet of the Red- Tailed Hawk are all yellow. The cry of the Red-Tailed Hawk is a two to three second hoarse, rasping scream, described as kree- eee-ar. This cry is often described as sounding similar to a steam whistle. This hawk soars; fl apping its wings as little as possible to conserve energy. Active fl ight is slow and deliberate, with deep wing beats. When soaring or fl apping its wings, it typically travels from 32 to 64 km/hr, but when diving it may exceed 190 km/hr. -

Revised January 19, 2018 Updated June 19, 2018

BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION / BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT FOR TERRESTRIAL AND AQUATIC WILDLIFE YUBA PROJECT YUBA RIVER RANGER DISTRICT TAHOE NATIONAL FOREST REVISED JANUARY 19, 2018 UPDATED JUNE 19, 2018 PREPARED BY: MARILYN TIERNEY DISTRICT WILDLIFE BIOLOGIST 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 3 II. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 4 III. CONSULTATION TO DATE ...................................................................................................... 4 IV. CURRENT MANAGEMENT DIRECTION ............................................................................... 5 V. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED PROJECT AND ALTERNATIVES ......................... 6 VI. EXISTING ENVIRONMENT, EFFECTS OF THE PROPOSED ACTION AND ALTERNATIVES, AND DETERMINATION ......................................................................... 41 SPECIES-SPECIFIC ANALYSIS AND DETERMINATION ........................................................... 54 TERRESTRIAL SPECIES ........................................................................................................................ 55 WESTERN BUMBLE BEE ............................................................................................................. 55 BALD EAGLE ............................................................................................................................... -

Immature Northern Goshawk Captures, Kills, and Feeds on Adult&Hyphen

DECEMUER2003 SHO•tT COMMUNICATIONS 337 [EDs.], Proceedingsof the 4th Workshop of Bearded Vulture (Gypaetusbarbatus) in the Pyrenees:influence Vulture. Natural History Museum of Crete and Uni- on breeding success.Bird Study46:224-229. versity of Crete, Iraklio, Greece. --AND --. 2002. Pla de recuperaci6 del trenca- --AND M. RAZIN.1999. Ecologyand conservationof 16s a Catalunya: biologia i conservaci6. Documents the Bearded Vultures: the case of the Spanish and dels Quaderns de Medi Ambient, 7. Generalitat de French Pyrenees.Pages 29-45 in M. Mylonas [ED.], Catalunya, Departament de Medi Ambient, Barcelo- Proceedingsof the Bearded Vulture Workshop. Nat- na, Spain. ural History Museum of Crete and University of , ---,J. BERTP,AN, ANt) R. HERrre^. 2003. Breed- Crete, Iraklio, Greece. ing biology and successof the Bearded Vulture HIRALDO,F., M. DELIBES,ANDJ. CALDER(SN. 1979. E1 Que- (Gypaetusbarbatus) in the eastern Pyrenees.Ibis 145 brantahuesos(Gypaetus barbatus). L. Monografias 22. 244-252. ICONA, Madrid, Spain. , --, AND R. HE•Em^. 1997. Estimaci6n de la MARGAiJDA,A. ANDJ. BERTRAN.2000a. Nest-buildingbe- disponibilidad tr6fica para el Quebrantahuesosen Ca- haviour of the Bearded Vulture (Gypaetusbarbatus). talufia (NE Espafia) e implicacionessobre su conser- Ardea 88:259-264. vaci6n. Do•ana, Acta Vertetm24:227-235. --AND --. 2000b. Breeding behaviour of the NEWTON,I. 1979. Populationecology ofraptors. T. &A D Bearded Vulture (Gypaetusbarbatus): minimal sexual Poyser,Berkhamsted, UK. differencesin parental activities.Ibis 142:225-234. ß 1986. The Sparrowhawk.T. & A.D. Poyser,Cal- --AND --. 2001. Function and temporal varia- ton, UK. tion in the use of ossuaries by Bearded Vultures --^NO M. MA•QUtSS.1982. Fidelity to breeding area (Gypaetusbarbatus) during the nestling period. -

Endangered and Threatened Species

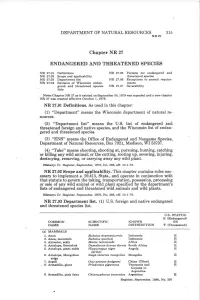

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 315 NR27 Chapter NR 27 ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES NR 27.01 Definitions NR 27 .05 Permits for endangered and NR 27.02 Scope end applicability threatened species NR 27.03 Department list NR 27 .06 Exceptions to permit require NR 27.04 Revision of Wisconsin endan ments gered and threatened species NR 27.07 Severability lists Note: Chapter NR 27 es it existed on September 30, 1979 was repealed and a new chapter NR 27 was created effective October 1, 1979. NR 27.01 Definitions. As used in this chapter: (1) "Department" means the Wisconsin department of natural re sources. (2) "Department list" means the U.S. list of endangered and threatened foreign and native species, and the Wisconsin list of endan gered and threatened species. (3) "ENS" means the Office of Endangered and Nongame Species, Department of Natural Resources, Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707. (4) "Take" means shooting, shooting at, pursuing, hunting, catching or killing any wild animal; or the cutting, rooting up, severing, injuring, destroying, removing, or carrying away any wild plant. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.02 Scope and applicability. This chapter contains rules nec essary to implement s. 29.415, Stats., and operate in conjunction with that statute to govern the taking, transportation, possession, processing or sale of any wild animal or wild plant specified by the department's lists of endangered and threatened wild animals and wild plants. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.03 Department list. -

Variation in the Procoracoid Foramen in the Accipitridae

Z6f Riv. Hal. Orn., Milano, 57 (3-4): 161-184, 15-XII-19B7 STORRS L. OLSON (*) VARIATION IN THE PROCORACOID FORAMEN IN THE ACCIPITRIDAE Abstract. — The procoracoid foramen of the eoracoid is present in the great majority of genera of Accipitridae. It may be nearly or completely absent in indivi- duals of Circus and Harpagus, the taxonomic significance of which is uncertain. The procoracoid foramen is invariably absent in the genus Accipiter, although the con- dition is still unknown in Erythrotriorchis and Megatriorchis which have sometimes been synonymized with Accipiter. The presence of a well developed procoracoid fo- ramen in Urotriorchis suggests that this genus may not be as closely related to Accipiter as has been assumed. Riassunto. — Variazione nel forame procoracoideo degli Accipitridae. II forame procoracoideo del coraeoide e presente nella maggioranza del generi degli Accipitridi. Esso puo essere quasi o completamente assente in individui di Circus e di Harpagus, fatto dal significato tassonomico incerto. II forame procora- coideo e invariabilmente assente nel genere Accipiter, sebbene tale condizione sia an- cora sconosciuta per i generi Erythrotriorchis e Megatriorchis, a volte posti in sino- nimia con Accipiter. La presenza di un forame procoracoideo ben sviluppato in Uro- triorchis suggerisce che questo genere possa non essere cosi strettamente affine ad Accipiter, come e stato ritenuto. Anatomical characters that may be of use in defining natural sub- divisions of the large and complex family Accipitridae are much to be desired, as, for example, the fused condition of the phalanges of the inner toe (OLSON 1982). Another feature that shows significant variation in the family is the procoracoid process of the eoracoid, the condition of which is worth documenting not just for systematic information but also for purposes of identification of archeological and paleontological materials. -

1 Northern Goshawk Forest Type Preference in the Chippewa

Northern Goshawk Forest Type Preference in the Chippewa National Forest Travis W. Ludwig Department of Resource Analysis, Saint Mary’s University of MN, Winona, MN 55987 Keywords: Goshawk, Accipiter gentilis, GIS, forest stands, Chippewa National Forest, minimal convex polygons, quaking aspen Abstract The Chippewa National Forest has large expanses of land that are densely forested and largely uninhabited providing excellent habitat for Northern Goshawk (Accipiter gentiles). The Chippewa National Forest is currently updating its forest management plan and one of the issues is the importance of goshawk habitat. The goshawk is a listed Sensitive Species in the Eastern Region for the U.S. Forest Service. This study used a geographic information system to assess which forest types are important as goshawk habitat. Since limited knowledge exists concerning goshawk habitat, three habitat estimations (minimal convex polygons, Kernel 95% and Forage Buffer) were used to determine which forest stands occur within goshawk utilization areas. While quaking aspen plays a vital role in goshawk habitat in the Chippewa National Forest, goshawks there are opportunistic and take advantage of many other forest types. Introduction The Chippewa National Forest, hereafter called Chippewa NF, encompasses 1.6 million acres. Of this, 666,325 acres are managed by the USDA Forest Service. The forest consists of aspen, birch, pine, balsam fir, and maple species. The Chippewa NF contains approximately 1300 lakes, 900 miles of rivers and streams, and 400,000 acres of wetlands. The Chippewa NF is the largest national forest east of the Mississippi (Chippewa National Forest Website, 2002). The Chippewa NF is located in northern Minnesota between the cities of Grand Rapids to the east and Bemidji to the west (Figure 1). -

Raptors in the East African Tropics and Western Indian Ocean Islands: State of Ecological Knowledge and Conservation Status

j. RaptorRes. 32(1):28-39 ¸ 1998 The Raptor ResearchFoundation, Inc. RAPTORS IN THE EAST AFRICAN TROPICS AND WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS: STATE OF ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND CONSERVATION STATUS MUNIR VIRANI 1 AND RICHARD T. WATSON ThePeregrine Fund, Inc., 566 WestFlying Hawk Lane, Boise,1D 83709 U.S.A. ABSTRACT.--Fromour reviewof articlespublished on diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey occurringin Africa and the western Indian Ocean islands,we found most of the information on their breeding biology comesfrom subtropicalsouthern Africa. The number of published papers from the eastAfrican tropics declined after 1980 while those from subtropicalsouthern Africa increased.Based on our KnoM- edge Rating Scale (KRS), only 6.3% of breeding raptorsin the eastAfrican tropicsand 13.6% of the raptorsof the Indian Ocean islandscan be consideredWell Known,while the majority,60.8% in main- land east Africa and 72.7% in the Indian Ocean islands, are rated Unknown. Human-caused habitat alteration resultingfrom overgrazingby livestockand impactsof cultivationare the main threatsfacing raptors in the east African tropics, while clearing of foreststhrough slash-and-burnmethods is most important in the Indian Ocean islands.We describeconservation recommendations, list priorityspecies for study,and list areasof ecologicalunderstanding that need to be improved. I•y WORDS: Conservation;east Africa; ecology; western Indian Ocean;islands; priorities; raptors; research. Aves rapacesen los tropicos del este de Africa yen islasal oeste del Oc•ano Indico: estado del cono- cimiento eco16gicoy de su conservacitn RESUMEN.--Denuestra recopilacitn de articulospublicados sobre aves rapaces diurnas y nocturnasque se encuentran en Africa yen las islasal oeste del Octano Indico, encontramosque la mayoriade la informaci6n sobre aves rapacesresidentes se origina en la regi6n subtropical del sur de Africa. -

A Partial Post-Juvenile Molt and Transitional Plumage in the Shikra (Accipiter Badius) and Grey Frog Hawk ( a Ccipiter Soloensis)

THE JOURNAL OF RAPTOR RESEARCH A QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF • THE RAPTOR RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. VOL. 34 DECEMBER 2000 NO. 4 J. RaptorRes. 34(4) :249-261 ¸ 2000 The Raptor Research Foundation, Inc. A PARTIAL POST-JUVENILE MOLT AND TRANSITIONAL PLUMAGE IN THE SHIKRA (ACCIPITER BADIUS) AND GREY FROG HAWK ( A CCIPITER SOLOENSIS) MARC HERREMANS AND MICHEL LOUETTE RoyalMuseum for CentralAfrica, Department Zoology, Leuvensesteenweg 13, B-3080 Tervuren,Belgium ABSTRACT.--Molthas been poorly studied in the Accipitridae. Examination of museum specimens showedthat there are three age-relatedplumages in the Shikra (Accipiterbadius) and Grey Frog Hawk (A. soloensis)similar to the pattern known in the Levant Sparrowhawk(A. brevipes).The juvenile plumage with its distinctively-spottedunderside is replacedby a transitionalpost-juvenile plumage during a partial contour molt between 4-10 mo of age. More feathers on the ventral side than on the dorsal side are replaced during this first contour molt, which is arrested at variousstages of incomplete feather replace- ment. Usually, a significantpart of the ventral pattern changesfrom spotted to barred, whereby the barring is on averagemore prominent than in adults. The early development of a transitional post- juvenile plumage might be related to early sex signaling.The adult plumage replacesthe transitional post-juvenileplumage during a completemolt at about one year of age. In the subspeciesA. b.poliopsis of the Shikra, which has almost no sexual dimorphism in the adult plumage, the transitional plumage is uncommon and very poorly developed. KEYWORDS: Shikra;Accipiter badius; Greyb?og Hawk; Accipiter soloensis;Levant Sparrowhawk; Accipiter brevipes;contour molt;, transitional post-juvenile plumage. Muda parcial postjuvenil y de transicionde plumaje en Accipiterbadius y Accipitersoloensis RES0MEN.--Lamuda ha sido poco esmdiada en las Accipitridae.