Brettsmithersthesis2003.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Studies Overview

Chapter 7. Bird Studies Overview teigerwald Lake National Wildlife Refuge provides a variety of habitats for many species of birds. Thousands of breeding birds rely on the resources of the refuge to Srest, eat, and raise their young. In addition, the refuge supports wetlands that are vital to the survival of migratory birds. The activities that follow offer an excellent opportunity for students to learn about and to observe the different species of birds — their behaviors and adaptations to the habitats on the refuge. Background The actively managed refuge wetlands and grasslands, when combined with the natural floodplain vegetative communities, provide habitat that supports over 200 species of birds. Hundreds of thousands of birds migrate along the lower Columbia River every year. The refuge hosts thousands of migratory birds that fly thousands of miles from their breeding grounds in Arctic Canada and Alaska to their wintering grounds in Baja California or South America, a route known as the Pacific Flyway. The few remaining areas of wetland habitat along the lower Columbia River are vital to the flyway. Some birds spend their winter on refuge wetlands, returning north to nest; some nest here but migrate to milder climates in the south for the winter; and some do not migrate at all but remain in the area as permanent residents. Several of the songbirds found in the summer spend our winters in Central and South America, migrating thousands of miles annually between their summer and winter habitats. Birds using the refuge are specifically adapted to the type of food they eat and the type of habitat they occupy (open water, freshwater wetland, field, riparian woodland, or upland woodland). -

THE LONG-EARED OWL INSIDE by CHRIS NERI and NOVA MACKENTLEY News from the Board and Staff

WINTER 2014 TAKING FLIGHT NEWSLETTER OF HAWK RIDGE BIRD OBSERVATORY The elusive Long-eared Owl Photo by Chris Neri THE LONG-EARED OWL INSIDE by CHRIS NERI and NOVA MACKENTLEY News from the Board and Staff..... 2 For many birders thoughts of Long-eared Owls invoke memories of winter Education Updates .................. 4 visits to pine stands in search of this often elusive species. It really is magical Research Features................... 6 to enter a pine stand, find whitewash and pellets at the base of trees and realize that Long-eareds are using the area that you are searching. You scan Stewardship Notes ................. 12 up the trees examining any dark spot, usually finding it’s just a tangle of Volunteer Voices.................... 13 branches or a cluster of pine needles, until suddenly your gaze is met by a Hawk Ridge Membership........... 14 pair of yellow eyes staring back at you from a body cryptically colored and Snore Outdoors for HRBO ......... 15 stretched long and thin. This is often a birders first experience with Long- eared Owls. However, if you are one of those that have journeyed to Hawk Ridge at night for one of their evening owl programs, perhaps you were fortunate enough to see one of these beautiful owls up close. CONTINUED ON PAGE 3 HAWK RIDGE BIRD OBSERVATORY 1 NOTES FROM THE DIRECTOR BOARD OF DIRECTORS by JANELLE LONG, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR As I look back to all of the accomplishments of this organization, I can’t help but feel proud CHAIR for Hawk Ridge Bird Observatory and to be a part of it. -

Crows and Ravens Wildlife Notes

12. Crows & Ravens Crows and ravens belong to the large family Corvidae, along with more than 200 other species including jays, nutcrackers and magpies. These less-than-melodious birds, you may be surprised to learn, are classified as songbirds. raven American Crow insects, grain, fruit, the eggs and young of other birds, Crows are some of the most conspicuous and best known organic garbage and just about anything that they can find of all birds. They are intelligent, wary and adapt well to or overpower. Crows also feed on the carcasses of winter – human activity. As with most other wildlife species, crows and road-killed animals. are considered to have “good” points and “bad” ones— value judgements made strictly by humans. They are found Crows have extremely keen senses of sight and hearing. in all 50 states and parts of Canada and Mexico. They are wary and usually post sentries while they feed. Sentry birds watch for danger, ready to alert the feeding birds with a sharp alarm caw. Once aloft, crows fly at 25 Biology to 30 mph. If a strong tail wind is present, they can hit 60 Also known as the common crow, an adult American mph. These skillful fliers have a large repertoire of moves crow weighs about 20 ounces. Its body length is 15 to 18 designed to throw off airborne predators. inches and its wings span up to three feet. Both males Crows are relatively gregarious. Throughout most of the and females are black from their beaks to the tips of their year, they flock in groups ranging from family units to tails. -

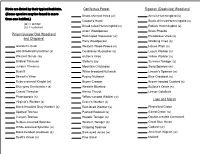

Common Birds of the Prescott Area Nuthatch.Cdr

Birds are listed by their typical habitats. Coniferous Forest Riparian (Creekside) Woodland (Some species may be found in more Sharp-shinned Hawk (w) Anna's Hummingbird (s) than one habitat.) Cooper's Hawk Black-chinned Hummingbird (s) (w) = winter (s) = summer Broad-tailed Hummingbird (s) Rufous Hummingbird (s) Acorn Woodpecker Black Phoebe Pinyon/Juniper/Oak Woodland Red-naped Sapsucker (w) Plumbeous Vireo (s) and Chaparral Hairy Woodpecker Warbling Vireo (s) Gambel's Quail . Western Wood-Pewee (s) House Wren (s) Ash-throated Flycatcher (s) Cordilleran Flycatcher (s) Lucy's Warbler (s) Western Scrub-Jay Hutton's Vireo Yellow Warbler (s) Bridled Titmouse Steller's Jay Summer Tanager (s) Juniper Titmouse . Mountain Chickadee Song Sparrow (w) Bushtit White-breasted Nuthatch Lincoln's Sparrow (w) Bewick's Wren . Pygmy Nuthatch Blue Grosbeak (s) Ruby-crowned Kinglet (w) Brown Creeper Brown-headed Cowbird (s) Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (s) Western Bluebird Bullock's Oriole (s) Crissal Thrasher Hermit Thrush Lesser Goldfinch Phainopepla (s) Yellow-rumped Warbler (w) Lake and Marsh Virginia's Warbler (s) Grace's Warbler (s) Black-throated Gray Warbler (s) Red-faced Warbler (s) Pied-billed Grebe Spotted Towhee Painted Redstart (s) Eared Grebe (w) Canyon Towhee Hepatic Tanager (s) Double-crested Cormorant Rufous-crowned Sparrow Western Tanager (s) Great Blue Heron White-crowned Sparrow (w) Chipping Sparrow Gadwall (w) Black-headed Grosbeak (s) Dark-eyed Junco (w) American Wigeon (w) Scott’s Oriole (s) Pine Siskin Mallard Lake and Marsh (cont.) Varied or Other Habitats Cinnamon Teal (s) Turkey Vulture (s) Common Birds Northern Shoveler (w) Red-tailed Hawk Northern Pintail (w) Rock Pigeon of the Green-winged Teal (w) Eurasian Collared-Dove Prescott Canvasback (w) Mourning Dove Ring-necked Duck (w) Greater Roadrunner Area Lesser Scaup (w) Ladder-backed Woodpecker Bufflehead (w) Northern Flicker Common Merganser (w) Cassin's Kingbird (s) Ruddy Duck (w) Common Raven American Coot Violet-green Swallow (s) . -

Educator's Guide

Educator’s Guide the jill and lewis bernard family Hall of north american mammals inside: • Suggestions to Help You come prepared • essential questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for teaching in the exhibition • map of the Exhibition • online resources for the Classroom • Correlations to science framework • glossary amnh.org/namammals Essential QUESTIONS Who are — and who were — the North as tundra, winters are cold, long, and dark, the growing season American Mammals? is extremely short, and precipitation is low. In contrast, the abundant precipitation and year-round warmth of tropical All mammals on Earth share a common ancestor and and subtropical forests provide optimal growing conditions represent many millions of years of evolution. Most of those that support the greatest diversity of species worldwide. in this hall arose as distinct species in the relatively recent Florida and Mexico contain some subtropical forest. In the past. Their ancestors reached North America at different boreal forest that covers a huge expanse of the continent’s times. Some entered from the north along the Bering land northern latitudes, winters are dry and severe, summers moist bridge, which was intermittently exposed by low sea levels and short, and temperatures between the two range widely. during the Pleistocene (2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago). Desert and scrublands are dry and generally warm through- These migrants included relatives of New World cats (e.g. out the year, with temperatures that may exceed 100°F and dip sabertooth, jaguar), certain rodents, musk ox, at least two by 30 degrees at night. kinds of elephants (e.g. -

PPCO Twist System

A Brown-headed Nuthatch brings food to the nest. Color-coded leg bands enable the authors and their colleagues to discern the curious and potentially complex relationships among the various individuals at Tall Timbers Research Station on the Florida–Georgia line. Photo by © Tara Tanaka. photos by Tara Tanaka Tallahassee, Florida [email protected] 46 BIRDING • FEBRUARY 2016 arblers are gorgeous, jays boisterous, and sparrows elusive, Wbut words like “cute” and “adorable” come to mind when the conversation shifts to Brown-headed Nuthatches. The word “cute” doesn’t appear in the scientifc literature regularly, but science may help to explain its frequent association with nuthatch- es. The large heads and small bodies nuthatches possess have propor- tions similar to those found on young children. Psychologists have found that these proportions conjure up “innate attractive” respons- es among adult humans even when the proportions fall on strange objects (Little 2012). This range-restricted nuthatch associated with southeastern pine- woods has undergone steep declines in recent decades and is listed as a species of special concern in most states in which it breeds (Cox and Widener 2008). The population restricted to Grand Bahama Island appears to be critically endangered (Hayes et al. 2004). Add to these concerns some intriguing biology that includes helpers at the nest, communal winter roosts, seed caching, social grooming, and the use of tools, and you have some scintillating science all bound up in one “cute” and “adorable” package. James -

Accipiters.Pdf

Accipiters The northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis) and the sharp-shinned hawk (Accipiter striatus) are the Alaskan representatives of a group of hawks known as accipiters, with short, rounded wings (short in comparison with other hawks) and long tails. The third North American accipiter, the Cooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii) is not found in Alaska. Both native species are abundant in the state but not commonly seen, for they spend the majority of their time in wooded habitats. When they do venture out into the open, the accipiters can be recognized easily by their “several flaps and a glide” style of flight. General Description: Adult northern goshawks are bluish- gray on the back, wings, and tail, and pearly gray on the breast and underparts. The dark gray cap is accented by a light gray stripe above the red eye. Like most birds of prey, female goshawks are larger than males. A typical female is 25 inches (65 cm) long, has a wingspread of 45 inches (115 cm) and weighs 2¼ pounds (1020 g) while the average male is 19½ inches (50 cm) in length with a wingspread of 39 inches (100 cm) and weighs 2 pounds (880 g). Adult sharp-shinned hawks have gray backs, wings and tails (males tend to be bluish-gray, while females are browner) with white underparts barred heavily with brownish-orange. They also have red eyes but, unlike goshawks, have no eyestrip. A typical female weighs 6 ounces (170 g), is 13½ inches (35 cm) long with a wingspread of 25 inches (65 cm), while the average male weighs 3½ ounces (100 g), is 10 inches (25 cm) long and has a wingspread of 21 inches (55 cm). -

Annual Report

2016 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 Annual Report 1 Our Mission Ohio Wildlife Center is dedicated to fostering awareness and appreciation of Ohio’s native wildlife through rehabilitation, education and wildlife health studies. Table of Contents Our Work The Center operates the state’s largest, free native 2 Our Mission and Work wildlife animal hospital, which assessed and treated 3 Message from the Board Chair 4,525 wildlife patients from 54 Ohio counties in 2016. Now a statewide leader in wildlife animal rescue and and Executive Director rehabilitation, the Center includes a 20-acre outdoor 4 2016 Fast Facts for Wildlife Hospital Education Center and Pre-Release Facility in Delaware County. The free Wildlife Hospital is located in the lower 5 2016 Fast Facts for Education level of Animal Care Unlimited at 2661 Billingsley 6 Foundation Grants and Partnerships Road in Columbus. 7 Volunteer Impact A focal point of the Education Center is the permanent sanctuary for 59 animals, ranging from coyote and fox 8 The Barbara and Bill Bonner Family to hawks, owls, raccoons, turtles and a turkey. There Foundation Barn are 42 species represented and seven animal ambassador 9 Power of Partnerships species listed as threatened or species of concern in Ohio. 10 2016 Events The Pre-Release Facility is comprised of multiple flight enclosures, a waterfowl enclosure, a songbird aviary, 11 Financials and species-specific outdoor housing designed to 12 Wildlife Hospital Admissions support the final phase of rehabilitation for recovering hospital patients. Animals reside at the Pre-Release 14 Board of Trustees Facility with care and oversight as they acclimate to the 15 Thank you! elements. -

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Cottontail Rabbits

Cottontail Rabbits Biology of Cottontail Rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as Prey of Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the Western United States Photo Credit, Sky deLight Credit,Photo Sky Cottontail Rabbits Biology of Cottontail Rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as Prey of Golden Eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the Western United States U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Regions 1, 2, 6, and 8 Western Golden Eagle Team Front Matter Date: November 13, 2017 Disclaimer The reports in this series have been prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) Western Golden Eagle Team (WGET) for the purpose of proactively addressing energy-related conservation needs of golden eagles in Regions 1, 2, 6, and 8. The team was composed of Service personnel, sometimes assisted by contractors or outside cooperators. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Suggested Citation Hansen, D.L., G. Bedrosian, and G. Beatty. 2017. Biology of cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.) as prey of golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the western United States. Unpublished report prepared by the Western Golden Eagle Team, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Available online at: https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/Reference/Profile/87137 Acknowledgments This report was authored by Dan L. Hansen, Geoffrey Bedrosian, and Greg Beatty. The authors are grateful to the following reviewers (in alphabetical order): Katie Powell, Charles R. Preston, and Hillary White. Cottontails—i Summary Cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.; hereafter, cottontails) are among the most frequently identified prey in the diets of breeding golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) in the western United States (U.S.). -

Revised January 19, 2018 Updated June 19, 2018

BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION / BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT FOR TERRESTRIAL AND AQUATIC WILDLIFE YUBA PROJECT YUBA RIVER RANGER DISTRICT TAHOE NATIONAL FOREST REVISED JANUARY 19, 2018 UPDATED JUNE 19, 2018 PREPARED BY: MARILYN TIERNEY DISTRICT WILDLIFE BIOLOGIST 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... 3 II. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................... 4 III. CONSULTATION TO DATE ...................................................................................................... 4 IV. CURRENT MANAGEMENT DIRECTION ............................................................................... 5 V. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED PROJECT AND ALTERNATIVES ......................... 6 VI. EXISTING ENVIRONMENT, EFFECTS OF THE PROPOSED ACTION AND ALTERNATIVES, AND DETERMINATION ......................................................................... 41 SPECIES-SPECIFIC ANALYSIS AND DETERMINATION ........................................................... 54 TERRESTRIAL SPECIES ........................................................................................................................ 55 WESTERN BUMBLE BEE ............................................................................................................. 55 BALD EAGLE ............................................................................................................................... -

Immature Northern Goshawk Captures, Kills, and Feeds on Adult&Hyphen

DECEMUER2003 SHO•tT COMMUNICATIONS 337 [EDs.], Proceedingsof the 4th Workshop of Bearded Vulture (Gypaetusbarbatus) in the Pyrenees:influence Vulture. Natural History Museum of Crete and Uni- on breeding success.Bird Study46:224-229. versity of Crete, Iraklio, Greece. --AND --. 2002. Pla de recuperaci6 del trenca- --AND M. RAZIN.1999. Ecologyand conservationof 16s a Catalunya: biologia i conservaci6. Documents the Bearded Vultures: the case of the Spanish and dels Quaderns de Medi Ambient, 7. Generalitat de French Pyrenees.Pages 29-45 in M. Mylonas [ED.], Catalunya, Departament de Medi Ambient, Barcelo- Proceedingsof the Bearded Vulture Workshop. Nat- na, Spain. ural History Museum of Crete and University of , ---,J. BERTP,AN, ANt) R. HERrre^. 2003. Breed- Crete, Iraklio, Greece. ing biology and successof the Bearded Vulture HIRALDO,F., M. DELIBES,ANDJ. CALDER(SN. 1979. E1 Que- (Gypaetusbarbatus) in the eastern Pyrenees.Ibis 145 brantahuesos(Gypaetus barbatus). L. Monografias 22. 244-252. ICONA, Madrid, Spain. , --, AND R. HE•Em^. 1997. Estimaci6n de la MARGAiJDA,A. ANDJ. BERTRAN.2000a. Nest-buildingbe- disponibilidad tr6fica para el Quebrantahuesosen Ca- haviour of the Bearded Vulture (Gypaetusbarbatus). talufia (NE Espafia) e implicacionessobre su conser- Ardea 88:259-264. vaci6n. Do•ana, Acta Vertetm24:227-235. --AND --. 2000b. Breeding behaviour of the NEWTON,I. 1979. Populationecology ofraptors. T. &A D Bearded Vulture (Gypaetusbarbatus): minimal sexual Poyser,Berkhamsted, UK. differencesin parental activities.Ibis 142:225-234. ß 1986. The Sparrowhawk.T. & A.D. Poyser,Cal- --AND --. 2001. Function and temporal varia- ton, UK. tion in the use of ossuaries by Bearded Vultures --^NO M. MA•QUtSS.1982. Fidelity to breeding area (Gypaetusbarbatus) during the nestling period.