“Does Sexual Orientation Still Matter? the Impact of LGBT Candidate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mr Andrew Mackay and Ms Julie Kirkbride

House of Commons Committee on Standards and Privileges Mr Andrew Mackay and Ms Julie Kirkbride Fifth Report of Session 2010–11 Report and Appendices, together with formal minutes Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 19 October2010 HC 540 Published on 21 October 2010 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Committee on Standards and Privileges The Committee on Standards and Privileges is appointed by the House of Commons to oversee the work of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards; to examine the arrangements proposed by the Commissioner for the compilation, maintenance and accessibility of the Register of Members’ Interests and any other registers of interest established by the House; to review from time to time the form and content of those registers; to consider any specific complaints made in relation to the registering or declaring of interests referred to it by the Commissioner; to consider any matter relating to the conduct of Members, including specific complaints in relation to alleged breaches in the Code of Conduct which have been drawn to the Committee’s attention by the Commissioner; and to recommend any modifications to the Code of Conduct as may from time to time appear to be necessary. Current membership Rt hon Kevin Barron MP (Labour, Rother Valley) (Chair) Sir Paul Beresford MP (Conservative, Mole Valley) Annette Brooke MP (Liberal Democrat, Mid Dorset and North Poole) Rt hon Tom Clarke MP (Labour, Coatbridge, Chryston and Bellshill) Mr Geoffrey Cox MP (Conservative, Torridge and West Devon) Mr Jim Cunningham MP (Labour, Coventry South) Mr Oliver Heald MP (Conservative, North East Hertfordshire) Eric Ollerenshaw MP (Conservative, Lancaster and Fleetwood) Heather Wheeler MP (Conservative, South Derbyshire) Dr Alan Whitehead MP (Labour, Southampton Test) Powers The constitution and powers of the Committee are set out in Standing Order No. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

MEETING of the BOARD of TRUSTEES Items in Red Are

Trust Board, 19 May 2021 MEETING OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Items in red are confidential Minutes of a meeting of the Board of Trustees (“the Trustees”) of the Canal & River Trust (“the Trust”) held on Wednesday 19 May 2021 at 8:30am – 1pm at &Meetings, 150 Minories, London, EC3N 1LS Present: Allan Leighton, Chair Dame Jenny Abramsky, Deputy Chair Nigel Annett CBE (by Zoom) Ben Gordon Janet Hogben Sir Chris Kelly Jennie Price CBE (by Zoom) Tim Reeve Sarah Whitney (from 9.20am, during minute 21/032, by Zoom) Sue Wilkinson In attendance: Richard Parry, Chief Executive Julie Sharman, Chief Operating Officer Stuart Mills, Chief Investment Officer Simon Bamford, Asset Improvement Director Heather Clarke, Strategy, Engagement, and Impact Director Steve Dainty, Finance Director Tom Deards, Head of Legal & Governance Services and Company Secretary Mike Gooddie, People Director – by Zoom Gemma Towns, Corporate Governance Manager (minute-taker, by Zoom) Radojka Miljevic, Campbell Tickell (observer) Mandy Smith, Partner Engagement Team Manager (by Zoom, minute 21/035) Jodie Lees, Corporate Engagement & PPL Partner (by Zoom, minute 21/035) Stephen Gray, Corporate Engagement Partnerships Manager (by Zoom, 21/035) Hamish Shilliday, Head of Individual & Legacy Giving (by Zoom, minute 21/035) David Prisk, Asset Manager, Reservoirs (by Zoom, minute 21/037) Gwen Jefferson, Organisation Development Manager (by Zoom, minute 21/040) 21/029 WELCOME & APOLOGIES The Chair welcomed all attendees to the meeting. The Chair welcomed RM, who was observing the meeting as part of the Trust’s board effectiveness review. The Chair confirmed that notice of the meeting had been given to all Trustees and that a quorum was present. -

The Power of the Black Vote in 2015

POWER OF THE BLACK VOTE IN 2015 The Changing Face of England & Wales Parliamentary seats and their voters Sponsored by Table of Contents 3 Foreword - Simon Woolley 4-5 Executive Summary 6-7 List of Marginal Seats Measured by BME Impact 8 Voting and turnout 9 Methodology 10 BME Population 11 Individual BME Communities 12 Labour’s Challenge 13 Conservative’s Opportunity 14 Lib Dem’s Watershed 15 MP’s Vulnerable to BME Vote 16-63 Analysis of Parliamentary Seats © Operation Black Vote - August 2013 Researched, written and designed by Lester Holloway 2Assistance from Louise Alexander Changing Face of Britain Foreword lack and minority ethnic unemployment, education, Bvoters have been handed health and housing. the greatest opportunity ever What is also interesting about to effectively engage in British this data is the shift of where politics. BME political power has been. In Our groundbreaking research the past it was almost exclusively clearly shows that the BME vote in urban, inner city areas which could easily decide over 160 seats. barely changed political hands. The Coalition Government has Today this change is not only oc- governed the UK with a working curring in urban areas such as majority of just 83 seats. The data Croydon, Harrow and Ealing but that we are publishing therefore also outside urban areas, such speaks volumes; In a 168 marginal as Corby, Rossendale & Darwin, seats the BME electorate is larger Cheadle and Loughborough. than the majority in which the With this report we relish the seat was won. The BME electorate challenge to inspire an often cyni- could influence an even greater cal electorate to engage as never number of seats if, as predicted, before, and simultaneously to the election contest becomes ever inform our political leaders that tighter. -

M a Tth Ew P a Rris Matthew Parris 2

ISSSUESUE 22:: JAANUARYNUARY 22006006 Been passed this issue? Click here to receive FREE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE MMatthewatthew PParrisarris 22:32...:32... Exclusive interview RRaceace BBallbusterallbuster rreporteport AAcrosscross UUltramanltraman - HHawaiiawaii AAmerica!merica! TThehe GGreatreat BBritishritish TTreblereble OOverlandverland ttoo TTimbuktuimbuktu KKnackernacker CrackerCracker rreporteport AArere yyouou wwhoho yyouou tthinkhink yyouou aare?re? FFitit bbutut llonelyonely hheartsearts ....and..and mmuchuch mmore...!ore...! ISSUE 2: JANUARY 2006 Been passed this issue? Click here to receive FREE MAGAZINE MAGAZINE Matthew Parris Feedback 2:32... Exclusive interview Ad index Race Ballbuster report Across Ultraman - Hawaii America! The Great British Treble Ordinary people doing extraordinary things Overland to Timbuktu Knacker Cracker report Are you who you think you are? Fit but lonely hearts ...and much more...! 3 The Trionium Manifesto 24 Overland to Timbuktu Reasons to be cheerful... Intrepid reporter Cathy Hillman travels to the heart of Mali, visiting the Bandiagara Escarpment 4 Trionium letters and the Dogon Plateau on her way to Timbuktu. This issue’s front cover... After the first issue of Trionium magazine, we Jure Robic of Slovenia powers include a selection of your responses. 29 (B)race across America his way towards winning the solo This event is so tough that your head may just men’s category in the 3052 mile 6 Matthew Parris digs in for 2:32 fall off your shoulders with tiredness. (Don’t 2005 Race Across America (page Political commentator and columnist has a secret: believe us? Read the story!). 29). The race includes ascent of 110,000 feet, more than four times he is the fastest MP of all time (er, except Seb the height of Everest.. -

Shape of Things to Come?

SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME? PROFILING THE NEXT GENERATION OF HEALTH ADVOCATES IN PARLIAMENT #MakingPerfectSenseofHealth | @MHPHealth 1 Shape of Things to Come? FOREWORD PETE DIGGER MANAGING DIRECTOR, ENGINE | MHP The General Election result of “ A diminished Official Opposition December 2019 has effectively put means that backbench voices an end to the uncertainty around the are likely to be more influential UK’s departure from the European than ever.” Union. However, the exodus of a large As a result of the arithmetic in the House number of established backbench of Commons, the last Parliament was parliamentarians and likely changes characterised by stasis for the NHS, even to the structure of government despite May’s injection of cash and the present a new and uncharted development of the Long Term Plan. environment for those looking to There was no primary legislation, with action engage with policymakers. playing out in the corridors of NHS England, the Department and HM Treasury. Things will Nowhere is that more the case than in be different this time: December’s Queen’s healthcare, where a number of high-profile Speech contained five bills within health and MPs including former Health Committee Chair social care, with the most significant legislative Dr Sarah Wollaston and APPG for Cancer proposals proposed by NHS England still to Chair Nic Dakin are no longer in post. come. A sizable working Conservative majority means much of this will enter into law. However However, while the loss of those expert the opportunities for scrutiny and amendments voices in health and care is notable, there during the passage of any piece of legislation are many potential advocates among the gives Parliament a renewed sense of new intake of MPs. -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Monday Volume 517 25 October 2010 No. 58 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 25 October 2010 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2010 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Parliamentary Click-Use Licence, available online through the Office of Public Sector Information website at www.opsi.gov.uk/click-use/ Enquiries to the Office of Public Sector Information, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 4DU; e-mail: [email protected] HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON.DAVID CAMERON,MP,MAY 2010) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE—The Rt Hon. David Cameron, MP DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER AND LORD PRESIDENT OF THE COUNCIL—The Rt Hon. Nick Clegg, MP FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS—The Rt Hon. William Hague, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. George Osborne, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Kenneth Clarke, QC, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Theresa May, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Liam Fox, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,INNOVATION AND SKILLS—The Rt Hon. Vince Cable, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Iain Duncan Smith, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE—The Rt Hon. Chris Huhne, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH—The Rt Hon. Andrew Lansley, CBE, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 696 24 May 2021 No. 8 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 24 May 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. HER MAJESTY’S GOVERNMENT MEMBERS OF THE CABINET (FORMED BY THE RT HON. BORIS JOHNSON, MP, DECEMBER 2019) PRIME MINISTER,FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY,MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE AND MINISTER FOR THE UNION— The Rt Hon. Boris Johnson, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER—The Rt Hon. Rishi Sunak, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN,COMMONWEALTH AND DEVELOPMENT AFFAIRS AND FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE— The Rt Hon. Dominic Raab, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR THE HOME DEPARTMENT—The Rt Hon. Priti Patel, MP CHANCELLOR OF THE DUCHY OF LANCASTER AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE—The Rt Hon. Michael Gove, MP LORD CHANCELLOR AND SECRETARY OF STATE FOR JUSTICE—The Rt Hon. Robert Buckland, QC, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE—The Rt Hon. Ben Wallace, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR HEALTH AND SOCIAL CARE—The Rt Hon. Matt Hancock, MP COP26 PRESIDENT—The Rt Hon. Alok Sharma, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR BUSINESS,ENERGY AND INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY—The Rt Hon. Kwasi Kwarteng, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND PRESIDENT OF THE BOARD OF TRADE, AND MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES—The Rt Hon. Elizabeth Truss, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS—The Rt Hon. Dr Thérèse Coffey, MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION—The Rt Hon. -

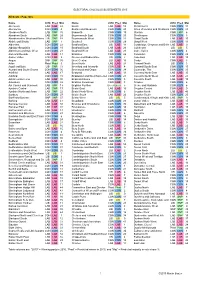

ELECTORAL CALCULUS SLIDESHEETS 2015 All Seats

ELECTORAL CALCULUS SLIDESHEETS 2015 All Seats - Page One Name___________________ 2010 Pred Maj Name___________________ 2010 Pred Maj Name___________________ 2010 Pred Maj Aberavon LAB LAB 42 Bootle LAB LAB 58 Christchurch CON CON 31 Aberconwy CON CON 5 Boston and Skegness CON CON 20 Cities of London and WestminsterCON CON 24 Aberdeen North LAB SNP 30 Bosworth CON CON 19 Clacton CON UKIP 6 Aberdeen South LAB SNP 29 Bournemouth East CON CON 25 Cleethorpes CON CON 3 Aberdeenshire West and KincardineLIB SNP 18 Bournemouth West CON CON 22 Clwyd South LAB LAB 15 Airdrie and Shotts LAB SNP 7 Bracknell CON CON 29 Clwyd West CON CON 11 Aldershot CON CON 22 Bradford East LIB LAB 14 Coatbridge, Chryston and BellshillLAB LAB 9 Aldridge-Brownhills CON CON 33 Bradford South LAB LAB 20 Colchester LIB LIB 5 Altrincham and Sale West CON CON 21 Bradford West LAB LAB 21 Colne Valley CON CON 4 Alyn and Deeside LAB LAB 14 Braintree CON CON 26 Congleton CON CON 22 Amber Valley CON LAB 5 Brecon and Radnorshire LIB CON 2 Copeland LAB LAB 15 Angus SNP SNP 35 Brent Central LIB LAB 16 Corby CON LAB 3 Arfon Plaid Plaid 3 Brent North LAB LAB 24 Cornwall North LIB CON 3 Argyll and Bute LIB SNP 33 Brentford and Isleworth CON LAB 4 Cornwall South East CON CON 15 Arundel and South Downs CON CON 36 Brentwood and Ongar CON CON 34 Cotswolds, The CON CON 33 Ashfield LAB LAB 17 Bridgend LAB LAB 13 Coventry North East LAB LAB 35 Ashford CON CON 31 Bridgwater and West Somerset CON CON 21 Coventry North West LAB LAB 21 Ashton under Lyne LAB LAB 30 Brigg and Goole CON CON 5 Coventry -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

Monday Volume 575 10 February 2014 No. 120 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 10 February 2014 £5·00 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2014 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 539 10 FEBRUARY 2014 540 sure that the teaching unions will recognise that this is House of Commons in their interests, and I hope they will embrace and support these changes. Monday 10 February 2014 Mr Barry Sheerman (Huddersfield) (Lab/Co-op): I know the Secretary of State sees himself as a big beast The House met at half-past Two o’clock at the Cabinet table championing educational reform, but is he aware that most of us who wish well for our educational system want the big beast to be controlled PRAYERS by good information, good research and good evidence? What is the evidence for the longer school day? [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] Michael Gove: The evidence is there in the gap between, for example, the performance of independent fee-paying schools and state schools. If one looks at those children who get the best results at the end of primary school Oral Answers to Questions and what happens to those who go on to independent schools and those who stay in the state sector, one sees that at the moment those who go on to independent schools are more likely to get good GCSEs and A-levels. EDUCATION A longer school day is one of the ingredients that we believe will make a difference. -

Mayoral Election

The 2004 London Elections Includes results from the 2005 Parliamentary General Election in London and from the 2006 London Borough Council General Elections Previous publications on local government elections General Election of Greater London Councillors - 9 April 1964 London Borough Council Elections - 7 May 1964 General Election of Greater London Councillors - 13 April 1967 London Borough Council Elections - 9 May 1968 Greater London Council Elections - 9 April 1970 London Borough Council Elections - 13 May 1971 Greater London Council Elections - 12 April 1973 London Borough Council Elections - 2 May 1974 Greater London Council Elections - 5 May 1977 London Borough Council Elections - 4 May 1978 Greater London Council Elections - 7 May 1981 London Borough Council Elections - 6 May 1982 London Borough Council Elections - 8 May 1986 Inner London Education Authority Direct Elections - 8 May 1986 London Borough Council Elections - 3 May 1990 London Borough Council By-elections - May 1990 to May 1994 London Borough Council Elections - 5 May 1994 London Borough Council Elections - 7 May 1998 London Borough Council Elections - 2 May 2002 Published 1964 to 1982 by the Greater London Council, 1986 by the London Residuary Body, 1990 to 1998 by the London Research Centre, and 2002 by the Greater London Authority. The London Elections 10 June 2004 The Parliamentary General Election 5 May 2005 The London Borough Council General Elections 4 May 2006 Michael Minors Dennis Grenham Copyright: Greater London Authority October 2006 Published by: Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk More London London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 10: 1 85261 916 3 ISBN 13: 978 1 85261 916 9 Acknowledgements: This publication has grown over two years and the authors recognise the considerable contribution made by the kind help, advice and support given by many people at the GLA. -

Daily Report Thursday, 24 June 2021 CONTENTS

Daily Report Thursday, 24 June 2021 This report shows written answers and statements provided on 24 June 2021 and the information is correct at the time of publication (06:29 P.M., 24 June 2021). For the latest information on written questions and answers, ministerial corrections, and written statements, please visit: http://www.parliament.uk/writtenanswers/ CONTENTS ANSWERS 6 Armed Forces: Housing 14 BUSINESS, ENERGY AND AWE 14 INDUSTRIAL STRATEGY 6 Mali: Peacekeeping Amazon: Competition 6 Operations 15 Business Premises: Rents 6 Navy: Shipping 15 Copyright 7 Type 26 Frigates: Iron and Medicine: Research 7 Steel 16 Merchant Shipping: Pensions 8 DIGITAL, CULTURE, MEDIA AND SPORT 17 Post Office: ICT 8 Broadband: Finance 17 Travel Agents: Coronavirus 9 Buses: Coronavirus 17 CABINET OFFICE 9 Choirs: Coronavirus 18 Civil Service Agencies: Re- employment 9 Gambling Commission: Reform 18 Coronavirus: Vaccination 10 Gambling: Internet 19 Government Property Agency: Mitie 10 Social Security Benefits: Voluntary Work 19 Ministers: ICT 11 Youth Investment Fund 20 Weddings: Coronavirus 12 Youth Services 20 CHURCH COMMISSIONERS 12 EDUCATION 21 Collective Worship: Coronavirus 12 Academies: Inspections 21 DEFENCE 13 Bletchley Park: Anniversaries 22 [Subject Heading to be Children: Coronavirus 22 Assigned] 13 Day Care: Children 23 Aircraft Carriers 14 Extracurricular Activities: Armed Forces: Coronavirus 14 Coronavirus 23 Newton Rigg College: Sales 25 Oman: Economic Situation 39 Newton Rigg College: Palestinians: Textbooks 39 University of Cumbria 25