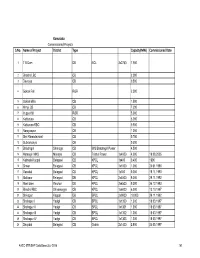

A Descriptive Analysis of Baseline Study in Haveri, Karnataka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rural Tourism As an Entrepreneurial Opportunity (A Study on Hyderabad Karnataka Region)

Volume : 5 | Issue : 12 | December-2016 ISSN - 2250-1991 | IF : 5.215 | IC Value : 79.96 Original Research Paper Management Rural Tourism as an Entrepreneurial Opportunity (a Study on Hyderabad Karnataka Region) Assistant Professor, Dept of Folk Tourism,Karnataka Folklore Mr. Hanamantaraya University, Gotagodi -581197,Shiggaon TQ Haveri Dist, Karnataka Gouda State, India Assistant Professor, Dept of Folk Tourism,Karnataka Folklore Mr. Venkatesh. R University, Gotagodi -581197,Shiggaon TQ Haveri Dist, Karnataka State, India The Tourism Industry is seen as capable of being an agent of change in the landscape of economic, social and environment of a rural area. Rural Tourism activity has also generated employment and entrepreneurship opportunities to the local community as well as using available resources as tourist attractions. There are numerable sources to lead business in the tourism sector as an entrepreneur; the tourism sector has the potential to be a development of entrepreneurial and small business performance. Which one is undertaking setting up of business by utilizing all kinds sources definitely we can develop the region of that area. This article aims to discuss the extent of entrepreneurial opportunities as the development ABSTRACT of tourism in rural areas. Through active participation among community members, rural entrepreneurship will hopefully move towards prosperity and success of rural tourism entrepreneurship Rural Tourism, Entrepreneurial opportunities of Rural Tourism, and Development of Entrepre- KEYWORDS neurship in Rural area Introduction Objectives of the studies Top tourism destinations, particularly in developing countries, 1. To know the entrepreneurial opportunities in Rural are include national parks, wilderness areas, mountains, lakes, and of HK region cultural sites, most of which are generally rural. -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.7631(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 3 | decembeR - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ “TOURISM IN HYDERABAD KARNATAKA REGION: A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE” Dr. Aanjaneya Guest Faculty , Dept. of Economics , Government Womens Degree College , Old Jewargi Road Kalaburagi , Karnataka. ABSTRACT Tourism development is a priority for rural and regional areas of Hyderabad Karnataka Region. It’s considered to be economic bonanza for Hyderabad Karnataka districts because industrial development is very limited among six districts, being a labour –intensive industry the scope of employment is very vast. Hyderabad Karnataka is an area with great tourisms potential and provides immense business opportunity for backward region. The state is bestowed with beauty and rich of heritage monuments, ancient unidentified spots etc. Tourism is an industry capable of change the socio- cultural economic and environmental face of the world tourism is one of the largest and fastest growing industries in the world it has the potential to influence the living pattern of communities it is the collection of activities services and industries that deliver a travel experience including transportation, accommodation, eating and drinking establishments of retail shops, entertainment, business, and other hospitality services provided for individuals or groups of travelling from home. KEYWORDS: Potentiality, Tourist, Place, visitors, Development I. INTRODUCTION Tourism has become a phenomenon in both developed and developing economies across the globe, Tourism as a displacement activity, involves being away from home on a temporary short-term visit to and stay at places of interest outside one's domicile and work. United Nation World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) however put a time limit of within a year of stay outside the environment other than your home either for business, leisure or other purposes to the definition of tourism. -

11.13 Karnataka

11.13 KARNATAKA 11.13.1 Introduction Karnataka, the seventh largest State of the country, with a geographical area of 1,91,791 sq km accounts for 5.83% of the geographical area of the country. The State is located in the south western region of India and lies between 11°30' N to 18°30' N latitudes and 74°00' E to 78°30' E longitudes and is bordered by Maharashtra and Goa in the North, Telangana and Andhra Pradesh in the east, Kerala & Tamil Nadu on the South and the Arabian Sea on the West. The State can be divided into two distinct physiographic regions viz the 'Malnad' or hilly region comprising Western Ghats and 'Maidan' or plain region comprising the inland plateau of varying heights. The average annual rainfall varies from 2,000 mm to 3,200 mm and the average annual temperature between 25°C and 35°C. The Western Ghats, which has an exceptionally high level of biological diversity and endemism, covers about 60% of forest area of the State. East flowing rivers in Karnataka mainly Cauvery & Krishna along with its tributaries drain into Bay of Bengal and west flowing rivers mainly Sharavathi & Kali drain into Arabian Sea. The State has 30 districts, amongst which 5 are tribal and 6 are hill districts. As per the 2011 census, Karnataka has a population of 61.13 million, which is 5.05% of India's population. The rural and urban populations constitute 61.43% and 38.57% respectively. Tribal population is 6.96% of the State's population. -

HŒ臬 A„簧綟糜恥sµ, Vw笑n® 22.12.2019 Š U拳 W

||Om Shri Manjunathaya Namah || Shri Kshethra Dhamasthala Rural Development Project B.C. Trust ® Head Office Dharmasthala HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ, vw¯ºN® 22.12.2019 Š®0u®± w®lµu® îµ±°ªæX¯Š®N®/ N®Zµ°‹ š®œ¯‡®±N®/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛ‡®± wµ°Š® wµ°î®±N¯r‡®± ªRq® y®‹°£µ‡®± y®ªq¯ºý® D Nµ¡®w®ºruµ. Cu®Š®ªå 50 î®±q®±Ù 50 Oʺq® œµX®±Ï AºN® y®lµu®î®Š®w®±Ý (¬šµ¶g¬w®ªå r¢›Š®±î®ºqµ N®Zµ°‹/w®S®u®± š®œ¯‡®±N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ y®u®ï î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 25 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ î®±q®±Ù îµ±ªæX¯Š®N® œ®±uµÛSµ N®xÇ®Õ Hš¬.Hš¬.HŒ¬.› /z.‡®±±.› ïu¯ãœ®Áqµ‡µ²ºvSµ 3 î®Ç®Áu® Nµ©š®u® Aw®±„Â®î® î®±q®±Ù ®±š®±é 01.12.2019 NµÊ Aw®æ‡®±î¯S®±î®ºqµ 30 î®Ç®Á ï±°Š®u®ºqµ ) î®±±ºvw® œ®ºq®u® š®ºu®ý®Áw®NµÊ B‡µ±Ê ¯l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. š®ºu®ý®Áw®u® š®Ú¡® î®±q®±Ù vw¯ºN®î®w®±Ý y®äqµã°N®î¯T Hš¬.Hº.Hš¬ î®±²©N® ¯Ÿr x°l®Œ¯S®±î®¼u®±. œ¯cŠ¯u® HŒ¯å A„®ãtÁS®¢Sµ A†Ãw®ºu®wµS®¡®±. Written test Sl No Name Address Taluk District mark Exam Centre out off 100 11 th ward near police station 1 A Ashwini Hospete Bellary 33 Bellary kampli 2 Abbana Durugappa Nanyapura HB hally Bellary 53 Bellary 'Sri Devi Krupa ' B.S.N.L 2nd 3 Abha Shrutee stage, Near RTO, Satyamangala, Hassan Hassan 42 Hassan Hassan. -

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date

Karnataka Commissioned Projects S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 1 T B Dam DB NCL 3x2750 7.950 2 Bhadra LBC CB 2.000 3 Devraya CB 0.500 4 Gokak Fall ROR 2.500 5 Gokak Mills CB 1.500 6 Himpi CB CB 7.200 7 Iruppu fall ROR 5.000 8 Kattepura CB 5.000 9 Kattepura RBC CB 0.500 10 Narayanpur CB 1.200 11 Shri Ramadevaral CB 0.750 12 Subramanya CB 0.500 13 Bhadragiri Shimoga CB M/S Bhadragiri Power 4.500 14 Hemagiri MHS Mandya CB Trishul Power 1x4000 4.000 19.08.2005 15 Kalmala-Koppal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x400 0.400 1990 16 Sirwar Belagavi CB KPCL 1x1000 1.000 24.01.1990 17 Ganekal Belagavi CB KPCL 1x350 0.350 19.11.1993 18 Mallapur Belagavi DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 29.11.1992 19 Mani dam Raichur DB KPCL 2x4500 9.000 24.12.1993 20 Bhadra RBC Shivamogga CB KPCL 1x6000 6.000 13.10.1997 21 Shivapur Koppal DB BPCL 2x9000 18.000 29.11.1992 22 Shahapur I Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1300 1.300 18.03.1997 23 Shahapur II Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1301 1.300 18.03.1997 24 Shahapur III Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1302 1.300 18.03.1997 25 Shahapur IV Yadgir CB BPCL 1x1303 1.300 18.03.1997 26 Dhupdal Belagavi CB Gokak 2x1400 2.800 04.05.1997 AHEC-IITR/SHP Data Base/July 2016 141 S.No. Name of Project District Type Capacity(MW) Commissioned Date 27 Anwari Shivamogga CB Dandeli Steel 2x750 1.500 04.05.1997 28 Chunchankatte Mysore ROR Graphite India 2x9000 18.000 13.10.1997 Karnataka State 29 Elaneer ROR Council for Science and 1x200 0.200 01.01.2005 Technology 30 Attihalla Mandya CB Yuken 1x350 0.350 03.07.1998 31 Shiva Mandya CB Cauvery 1x3000 3.000 10.09.1998 -

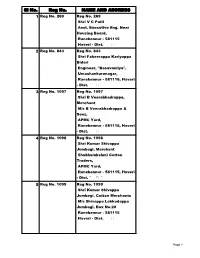

Sl No. Reg No. NAME and ADDRESS 1 Reg No

Sl No. Reg No. NAME AND ADDRESS 1 Reg No. 269 Reg No. 269 Shri V C Patil Asst. Executive Eng. Near Housing Board, Ranebennur - 581115 Haveri - Dist. 2 Reg No. 843 Reg No. 843 Shri Fakeerappa Kariyappa Bidari Engineer, "Basavanilya", Umashankaranagar, Ranebennur - 581115, Haveri - Dist. 3 Reg No. 1097 Reg No. 1097 Shri B Veerabhadrappa, Merchant M/s B Veerabhadrappa & Sons, APMC Yard, Ranebennur - 581115, Haveri - Dist. 4 Reg No. 1098 Reg No. 1098 Shri Kumar Shivappa Jumbegi, Merchant Shubhalakshmi Cotton Traders, APMC Yard, Ranebennur - 581115, Haveri - Dist. 5 Reg No. 1099 Reg No. 1099 Shri Kumar Shivappa Jumbegi, Cotton Merchants M/s Shivappa Lekkadappa Jumbagi, Box No.20 Ranebennur - 581115 Haveri - Dist. Page 1 6 Reg No. 1100 Reg No. 1100 Shri Channappa Puttappa Badave Merchant Badaami Building, Station Road, Ranebennur - 581115 Haveri - Dist. 7 Reg No. 1101 Reg No. 1101 Shri Kumar Shadaksharappa Musti S .S Musti Compay, APMC Yard Ranebennur - 581115, Haveri - Dist. 8 Reg No. 1102 Reg No. 1102 Shri Rudranna Veerabhadrappa Hosakeri Cotton Merchants, Hosakeri Compay, APMC Yard Ranebennur - 581115, Haveri - Dist. 9 Reg No. 1103 Reg No. 1103 Shri Viswanath Shekharappa Jumbegi Merchants, Vageeshanagar, Ranebennur - 581115, Haveri - Dist. 10 Reg No. 1104 Reg No. 1104 Shri Ramanagowda Linganagowda M/s.N G Patil, APMC Yard Ranebennur - 581115, Haveri - Dist. Page 2 11 Reg No. 1105 Reg No. 1105 Shri Shankara Karaveerappa Kottura Lecturer, Poni -Banglore Main Road, Near Bus Stand Ranebennur - 581115 Haveri - Dist. 12 Reg No. 1106 Reg No. 1106 Shri Mahadevappa Halappagowli Merchants, Gowli Street, Ranebennur - 581115 Haveri - Dist. 13 Reg No. -

CS KOPPAL KARNATAKA R0.Cdr

WATER SUPPLY Reliable pumping by SubVT pumpsets even at 30m depth Koppal, Karnataka. Koppal District located in the northern interior of Karnataka having an area of 8,458sq- km is surrounded by Raichur district in the east, Gadag district in the West, Bagalkot district in the north, Bellary district in the south. Koppal is closest to the UNESCO World Heritage site of HAMPI - the capital of Vijayanagara Empire in the 14th century. Chronicles left by Persian and European travellers, particularly the Portuguese are saying that state Hampi by 1500 CE; was the World's Second-Largest medieval-era city (after Beijing). CS KOPPAL KARNATAKA:Rev0 : Page 1 WATER SUPPLY Geographically, Koppal is a stretch of rocky terrain on one side and acres of dry land on the other hence water storage was always a problem & water lean crops like Jowar, Ground-nuts etc were grown. But now, after the Thunga-Bhadra river waters from the neighbouring town of Munirabad (20kms away) have been dammed up with a huge Dam - i.e. TungaBhadra dam; water availability is not a problem - indeed high-tech irrigational Farming (pomegranates, grapes, figs, etc) are being now cultivated by gravity irrigation & Koppal district is the best seed production center in the country. But despite water availability in the dam; this also poses problems for Lifing water via pumpsets - the depth of column pipes is almost 30m & 24m water level variation (between Monsoon & Summer) means very robust pumps are required...! TB dam has very high silt inflow & most of it is ferrite rich - i.e. abrasive in nature ! WSS Koppal District : End customer : Karnataka Urban Water Supply & Sewage Board Type of Pump : HT Submerged Turbine pump installed in Jack well Suspension Length : ~30m Location : Tungabhadra dam near Hospet CS KOPPAL KARNATAKA:Rev0.2 : Page 2 Robust & Reliable WATER SUPPLY • Minimum breakdown even in High Silt levels • No breakdown for Deeper Column Lengths even upto 120m due to the Elimination of Couplings, Fragile Line Shafts & its Water Lubricated Line Shaft Bearings, Spiders, etc. -

State of Conservation Report Regarding Progress So Far Made with Regard to the Recommendations of the World Heritage Committee in Decision 37COMB.61

Name of the Property: Group of Monuments at Hampi (India) (C 241) State of Conservation report regarding progress so far made with regard to the recommendations of the World Heritage Committee in Decision 37COMB.61. 1. Response from the State Party to the World Heritage Committee’s Decision, 37 COM 7B.61 , paragraph by paragraph A. Removal of debris of the collapsed bridge and the relocation of the vehicular bridge outside of the property; The Public Works Department of Government of Karnataka, has resumed the work of removing the remaining part of the collapsed bridge viz., debris, columns and carriageway, without disturbing the nearby cultural resources, by adopting state of the art technology and the work is almost complete. As regards the relocation of the vehicular bridge, cultural impact assessment study has been completed and location of the vehicular bridge as recommended in the impact assessment study has been identified. B. Completed Integrated Management Plan together with a synthesis and a prioritisation of existing recommendations and intentions, for review by the World Heritage Centre and the Advisory Bodies - The Integrated Management Plan (draft already submitted to the WHC in 2006) gives an overall framework for the Management & protection of Hampi World Heritage Site. It is reiterated that as per the draft IMP recommendations the following actions have been implemented since January 2006 by Government of Karnataka and Archaeological Survey of India. Sno IMP recommendation Agency 1 Preparing a official Base Map HWHAMA -

Role of Haveri District Leaders in the National Movement – a Case Study

© 2019 JETIR June 2019, Volume 6, Issue 6 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) Role of Haveri District Leaders in the National Movement – A case study * Mamata Sawakar, Asst Professor, Dept of Political Science, Govt First Grade College,Ranebennur **Dr.Prasannakumar.K, Asst Professor, Dept of Political Science, Sahyadri Arts & Commerce College, Shimoga. Abstract Haveri district is exactly in the center of Karnataka with equal distance from Bidar in the far north to Kollegal in the far south. It is also known as the gateway district to the northern districts of Karnataka. Haveri district has a very rich culture and tradition. The district is proud to be the birth place of Santa Shishunala Sharif, great saint Kanakadasaru, Sarvagnya, Hanagal Kumara Shivayogigalu, Wagish Panditaru, Writer Galaganatharu, Ganayogi Panchakshari Gavayigalu, Gnyana Peetha Awardee Dr.V.K.Gokak and many more. The freedom fighter Mailara Mahadevappa, who resisted British rule, is from Motebennur in Haveri District. Another freedom fighter Gudleppa Hallikere a native of Hosaritti is also from this district. He started a residential school Gandhi Grameen Gurukul in Hosaritti. During the Quit India Movement, Gandhiji gave the clarion call ‘Do or die’. A great movement to oust the British was unleashed. Mahadevappa lead the movement of South division of Dharwad. He started Kara Nirakarane i.e. refusal to pay land revenue movement. He encouraged farmers not to pay land revenue to the Government. This movement spread like wild fire. The lands of those peasants who did not pay taxes were confiscated. Meanwhile, some peasants joined hands with the British and purchased those confiscated lands. -

Sustaining Landscapes of Heritage

Sustaining Landscapes of Cultural Heritage: The Case of Hampi, India Final Report to The Global Heritage Fund Produced by Morgan Campbell 2012 Sustaining Landscapes of Heritage This report is the result of the Global Heritage Fund’s 2011 Preservation Fellowship Program. Research was undertaken by Morgan Campbell, a PhD student of Urban Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University, during the summer of 2012. Global Heritage Fund Morgan Campbell 625 Emerson Street 200 [email protected] Palo Alto, CA 94301 www.globalheritagefund.org Sustaining Landscapes of Heritage ii Dedication I am incredibly grateful to numerous people for a variety of reasons. My time in Hampi during the summer of 2012 was one of the most significant experiences in my life. First, I dedicate this work to the Global Heritage Fund for providing me with the support to pursue questions of participatory planning in Hampi’s World Heritage Area. I thank James Hooper, whose earlier research in Hampi provided me with a good foundation and Dan Thompson who was incredibly understanding and supportive. Second, I’m deeply indebted to Shama Pawar of The Kishkindra Trust in Anegundi. Easily one of the most dynamic people I’ve ever met, without her assistance—which came in the form of conversations, tangible resources, and informal mentoring—I would have never been able to undergo this research project. It was because of Shama that I was able to experience and learn from Hampi’s living heritage. This report is about people, people who live in a heritage landscape. The residents of Hampi’s World Heritage Area are spread across time and space, so that when I say residents, I am referring to those living in the present and those who have lived in the past. -

District Profile Koppal, Karnataka

District Profile Koppal, Karnataka Koppal, a district of Karnataka state, carved out of Raichur district, came into existence on 1998. It consists of four talukas namely: Koppal, Gangavathi, Kushtagi and Yelburga. The headquarters is closest to the world heritage site - Hampi. There are 20 hoblies, 134 gram panchayats, four municipal corporations, 10 towns, 596 inhabitations/thandas and 41 uninhabited villages. DEMOGRAPHY As per Census 2011, the total population of Koppal is 1,389,920. Out of which 699,926 were males and 689,994 were females. This gives a sex ratio of 986 females per 1000 males. The percentage of urban population in Koppal is 16.81 percent, which is lower than the state average of 38.6 percent. The decadal growth rate of population in Karnataka is 15.60 percent, while Koppal reports a 16.21 percent decadal increase in the population. The decadal growth rate of urban population in Karnataka is 4.58 percent, while Koppal reports a 0.21 percent. The district population density is 250 in 2011, which has increased from 215 since 2001. The Scheduled Caste population in the district is 18.61 percent while Scheduled Tribe comprises 11.82 percent of the population. LITERACY The overall literacy rate of Koppal district is 68.09 percent while the male & female literacy rate is 78.54 and 57.55 percent respectively. At the block level, a considerable variation is noticeable in male-female literacy rate. Gangawati has the lowest literacy male rate at 76.5 percent. Consequently the female literacy rate in Yelburga is at a low 54.88 percent. -

Haveri District Karnataka West Graduates Constituency in the State

75°0'0"E 75°10'0"E 75°20'0"E 75°30'0"E 75°40'0"E 75°50'0"E N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 2 2 ° ° 5 5 1 Haveri District 1 Karnataka West Graduates Constituency in the State of Karnataka-2020 µ N N " " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 1 1 ° ° 5 5 1 Dharwad District 1 Muthalli Tadas Attigeri Basanal Kamalanagar Muthalli Thimmapur Panigatti Shisuvinal Kunnur Belwalakoppa Adavisomapur Neeralgi Hirebendigeri Chikbendigeri Hulgur Kadahalli Kyalkond Gudageri Surapgatti G Kunnur Belagali Gonala Shyadambi a Madapur d Mamadapur Hulsogi Kabanur Jekenakatti Chowdala a Hiremanakatti (Manakatti) Yelavigi g KengapurJekenakatti Maruthipura Huvinshigli Kunnur Madli Dhundshi Bisatikoppa Bannur D 96 Gotagodi Mugali Karadagi Bujruk Basapur Bannikoppa is Hesarur Sheelvant Somapur Wanahalli Hiremallur Chillur Badni Paramawadi Basavankoppa tr Kamanahalli Ganjigatti Honikop i N Jondalgatti Aratal c N " Makapur Chikmallur t " 0 0 ' Mantrodi Naikerur ' 0 Yattinahalli Shiggaon (TMC) Chillur Allipura 0 ° Shirabadgi ° SHIGGAON Kankanwad 5 95 Vadnikoppa Siddapur 5 1 95A 1 Hanumarahalli Gundur Shevalalpur Jakkankatti Motalli Bevinahalli BasavanakoppaHosur Kaliwal Shivapur Hosa Neeralgi-M-Karadgi (New) Kadakola Kerikop Chakapur 93 Khursapur Savanur (TMC) Bhairapur Gudisalkoppa Bhadrapur KonankeriNeeralakatti Chiknellur Savanur (RURAL) SAVANUR Hunshikatti Bisanhalli Teggihalli Kalalkond Ichangi MeundiTaredahalli Hottur Jallapur Bailmadapura Chandapur Kalyan NandihalliMannur Hattimattur Krishnapur Gudur Munavalli Mulkeri Nidagundi 94 Halagi Neeralagi-M-Guttal Ibrahimpur Mavoor (Mahur) Hiremaralihalli