1591743 Robert Stock Thesis 23 May 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE JUNGLE by Joe Murphy & Joe Robertson Directed by Stephen Daldry & Justin Martin

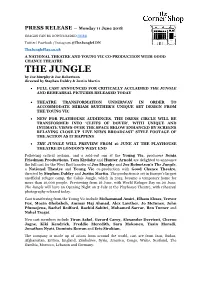

PRESS RELEASE – Monday 11 June 2018 IMAGES CAN BE DOWNLOADED HERE Twitter/ Facebook / Instagram @TheJungleLDN TheJunglePlay.co.uk A NATIONAL THEATRE AND YOUNG VIC CO-PRODUCTION WITH GOOD CHANCE THEATRE THE JUNGLE by Joe Murphy & Joe Robertson directed by Stephen Daldry & Justin Martin FULL CAST ANNOUNCED FOR CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED THE JUNGLE AND REHEARSAL PICTURES RELEASED TODAY THEATRE TRANSFORMATION UNDERWAY IN ORDER TO ACCOMMODATE MIRIAM BUETHER’S UNIQUE SET DESIGN FROM THE YOUNG VIC NEW FOR PLAYHOUSE AUDIENCES, THE DRESS CIRCLE WILL BE TRANSFORMED INTO ‘CLIFFS OF DOVER’, WITH UNIQUE AND INTIMATE VIEWS OVER THE SPACE BELOW ENHANCED BY SCREENS RELAYING CLOSE-UP ‘LIVE NEWS BROADCAST’ STYLE FOOTAGE OF THE ACTION AS IT HAPPENS THE JUNGLE WILL PREVIEW FROM 16 JUNE AT THE PLAYHOUSE THEATRE IN LONDON’S WEST END Following critical acclaim, and a sold-out run at the Young Vic, producers Sonia Friedman Productions, Tom Kirdahy and Hunter Arnold are delighted to announce the full cast for the West End transfer of Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson’s The Jungle, a National Theatre and Young Vic co-production with Good Chance Theatre, directed by Stephen Daldry and Justin Martin. The production is set in Europe’s largest unofficial refugee camp, the Calais Jungle, which in 2015, became a temporary home for more than 10,000 people. Previewing from 16 June, with World Refugee Day on 20 June, The Jungle will have an Opening Night on 5 July at the Playhouse Theatre, with rehearsal photography released today. Cast transferring from the Young Vic include Mohammad Amiri, Elham Ehsas, Trevor Fox, Moein Ghobsheh, Ammar Haj Ahmad, Alex Lawther, Jo McInnes, John Pfumojena, Rachel Redford, Rachid Sabitri, Mohamed Sarrar, Ben Turner and Nahel Tzegai. -

2014 Winter/Spring Season MAR 2014

2014 Winter/Spring Season MAR 2014 Bill Beckley, I’m Prancin, 2013, Cibachrome photograph, 72”x48” Published by: BAM 2014 Winter/Spring Sponsor: BAM 2014 Winter/Spring Season #ADOLLSHOUSE Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board A Karen Brooks Hopkins, President Doll’s Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer House By Henrik Ibsen English language version by Simon Stephens Young Vic Directed by Carrie Cracknell BAM Harvey Theater Feb 21 & 22, 25—28; Mar 1, 4—8, 11—15 at 7:30pm Feb 22; Mar 1, 8 & 15 at 2pm Feb 23; Mar 2, 9 & 16 at 3pm Approximate running time: two hours and 40 minutes, including one intermission BAM 2014 Winter/Spring Season sponsor: Set design by Ian MacNeil Costume design by Gabrielle Dalton Lighting design by Guy Hoare Music by Stuart Earl BAM 2014 Theater Sponsor Sound design by David McSeveney Leadership support for A Doll’s House provided by Choreography by Quinny Sacks Frederick Iseman Casting by Julia Horan CDG Associate director Sam Pritchard Leadership support for Scandinavian Hair, wigs, and make-up by Campbell Young programming provided by The Barbro Osher Pro Suecia Foundation Literal translation by Charlotte Barslund Major support for theater at BAM provided by: The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation The Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Inc. Donald R. Mullen Jr. Presented in the West End by Young Vic, The Morris and Alma Schapiro Fund The SHS Foundation Mark Rubinstein, Gavin Kalin, Neil Laidlaw The Shubert Foundation, Inc. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

The Beatles on Film

Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel - 885.p 170758668456 Roland Reiter (Dr. phil.) works at the Center for the Study of the Americas at the University of Graz, Austria. His research interests include various social and aesthetic aspects of popular culture. 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 2 ) T00_02 seite 2 - 885.p 170758668496 Roland Reiter The Beatles on Film. Analysis of Movies, Documentaries, Spoofs and Cartoons 2008-02-12 07-53-56 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02e7170758668448|(S. 3 ) T00_03 titel - 885.p 170758668560 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Universität Graz, des Landes Steiermark und des Zentrums für Amerikastudien. Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © 2008 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Layout by: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Edited by: Roland Reiter Typeset by: Roland Reiter Printed by: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar ISBN 978-3-89942-885-8 2008-12-11 13-18-49 --- Projekt: transcript.titeleien / Dokument: FAX ID 02a2196899938240|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum - 885.p 196899938248 CONTENTS Introduction 7 Beatles History – Part One: 1956-1964 -

Indirect Translation on the London Stage: Terminology and (In)Visibility

Indirect translation on the London stage: terminology and (in)visibility Geraldine Brodie* Centre for Translation Studies, University College London, UK *[email protected] Abstract Productions of translated plays on the London stage use a variety of terms to describe the interlingual interpretive process that has taken place between the source text and the performance. Most frequently, a translated play is described as a “version” or “adaptation”, with the term “translation” reserved for specialized productions. The translation method most commonly adopted is to commission a source-language expert to prepare a “literal” translation which is then used by an English-speaking theatre practitioner to produce a playscript for performance. This article examines the incidence of such indirect translation practices, the inconsistencies of the applied terminology, and the relevance for indirect translation in its wider sense, revealing the shadows of translational behaviour even within language pairs, and demonstrating the multiplicity of agents impacting on the ultimate appearance of a text in translation. Keywords: adaptation, literal translation, London theatre, theatre translation, version, indirect translation Introduction Translation is a collaborative exercise, incorporating a range of participants and stages in the trajectory between originating and ultimate texts. The romantic concept of the solitary, omniscient translator – Jerome, the patron saint of translators, alone in the desert with his bible and skull – is no longer apposite, if it ever were. The writer of the “letter of Aristeas” in around 130 BCE depicted seventy-two translators creating the early-third-century Septuagint translation of the Hebrew scripture, “making all details harmonize by mutual comparison” – although this was disputed by later authors, who preferred to ascribe the translation of sacred texts to divine inspiration (Robinson 2014, 4–5). -

Adrian Henri - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Adrian Henri - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Adrian Henri(10 April 1932 - 20 December 2000) Adrian Henri was a British poet and painter, best remembered as the founder of poetry-rock group The Liverpool Scene and as one of three poets in the best- selling anthology The Mersey Sound, along with <a href=" Adrian Henri's grandfather was a seaman from Mauritius who settled in Birkenhead, Cheshire, where Henri was born. In 1938, at the age of 6, Henri moved to Rhyl. Henri studied art at Newcastle and for a short time taught art at Preston Catholic College before going on later to lecture in art at both Manchester and Liverpool Colleges of Art. He was closely associated with other artists of the area and the era including the Pop artist Neville Weston and the conceptual artist Keith Arnatt. In 1972 he won a major prize for his painting in the John Moores competition. He was president of the Merseyside Arts Association and Liverpool Academy of the Arts in the 1970s and was an honorary professor of the city's John Moores University. He married twice, but had no children. His career spanned everything from artist and poet to teacher, rock-and-roll performer, playwright and librettist. He could name among his friends John Lennon, George Melly, <a href=" His numerous publications include The Mersey Sound, with McGough and Patten—a best-selling poetry anthology that brought all three of them to wider attention—Wish You Were Here and Not Fade Away. -

Yorkshire Poetry, 1954-2019: Language, Identity, Crisis

YORKSHIRE POETRY, 1954-2019: LANGUAGE, IDENTITY, CRISIS Kyra Leigh Piperides Jaques, BA (Hons) and MA, (Hull) PhD University of York English & Related Literature October 2019 This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (grant number AH/L503848/1) through the White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the writing of a large selection of twentieth- and twenty-first- century East and West Yorkshire poets, making a case for Yorkshire as a poetic place. The study begins with Philip Larkin and Ted Hughes, and concludes with Simon Armitage, Sean O’Brien and Matt Abbott’s contemporary responses to the EU Referendum. Aside from arguing the significance of Yorkshire poetry within the British literary landscape, it presents poetry as a central form for the region’s writers to represent their place, with a particular focus on Yorkshire’s languages, its identities and its crises. Among its original points of analysis, this thesis redefines the narrative position of Larkin and scrutinizes the linguistic choices of Hughes; at the same time, it identifies and explains the roots and parameters of a fascinating new subgenre that is emerging in contemporary West Yorkshire poetry. This study situates its poems in place whilst identifying the distinct physical and social geographies that exist, in different ways, throughout East and West Yorkshire poetry. Of course, it interrogates the overarching themes that unite the two regions too, with emphasis on the political and historic events that affected the region and its poets, alongside the recurring insistence of social class throughout many of the poems studied here. -

MEMO: Licensing Unit

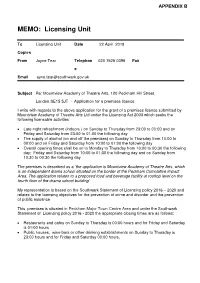

APPENDIX B MEMO: Licensing Unit To Licensing Unit Date 22 April 2019 Copies From Jayne Tear Telephon 020 7525 0396 Fax e Email [email protected] Subject Re: Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts, 120 Peckham Hill Street, London SE15 5JT - Application for a premises licence I write with regards to the above application for the grant of a premises licence submitted by Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts Ltd under the Licensing Act 2003 which seeks the following licensable activities: • Late night refreshment (indoors ) on Sunday to Thursday from 23:00 to 00:00 and on Friday and Saturday from 23:00 to 01:00 the following day • The supply of alcohol (on and off the premises) on Sunday to Thursday from 10:00 to 00:00 and on Friday and Saturday from 10:00 to 01:00 the following day • Overall opening times shall be on to Monday to Thursday from 10:00 to 00:30 the following day; Friday and Saturday from 10:00 to 01:30 the following day and on Sunday from 10:30 to 00:30 the following day The premises is described as a ‘the application is Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts, which is an independent drama school situated on the border of the Peckham Cumulative impact Area. The application relates to a proposed food and beverage facility at rooftop level on the fourth floor of the drama school building’ My representation is based on the Southwark Statement of Licensing policy 2016 – 2020 and relates to the licensing objectives for the prevention of crime and disorder and the prevention of public nuisance This premises is situated in Peckham Major Town Centre Area and under the Southwark Statement of Licensing policy 2016 - 2020 the appropriate closing times are as follows: • Restaurants and cafes on Sunday to Thursday is 00:00 hours and for Friday and Saturday is 01:00 hours • Public houses, wine bars or other drinking establishments on Sunday to Thursday is 23:00 hours and for Friday and Saturday 00:00 hours. -

Liverpool Poets (1960S)

ROUTE MAP English ® www.routeplanner-engels.nl © cetes.nl 2012 History of Literature: Poetry, Liverpool Poets (ERK B1, B2) B1 B2 Poetry Liverpool Poets (1960s) Adrian Henri Roger McGough Brian Patten pag. 1 ROUTE MAP English ® www.routeplanner-engels.nl © cetes.nl 2012 History of Literature: Poetry, Liverpool Poets (ERK B1, B2) Wat je in het algemeen moet kennen voor SE’s (SchoolExamens) 1. De hoofdkenmerken van de behandelde schrijvers en stromingen kennen en kunnen herkennen in de aange‐ boden teksten en ook in ongezien materiaal. 2. De vragen en opdrachten bij de behandelde teksten kunnen beantwoorden als je de tekst erbij krijgt. 3. Indien van toepassing, de ontwikkeling van een schrijver of een stroming kunnen uitleggen. 4. Schrijvers en hun werken kunnen vergelijken: overeenkomsten en verschillen. 5. Indien van toepassing, iets kunnen vertellen over het leven van de behandelde schrijvers voor zover dat be‐ trekking heeft op hun werk. 6. De schrijvers op basis van hun werk in de eeuw of in de tijd kunnen plaatsen. Liverpool poets From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Liverpool Poets are a number of influential 1960s poets from Liverpool, England, influenced by 1950s Beat poetry. They were involved in the 1960s Liverpool scene that gave rise to The Beatles. Their work is characterized by its directness of expression, simplicity of language, suitability for live performance and concern for contemporary subjects and references. There is often humour, but the full range of human experience and emotion is addressed. Poets The poets most commonly associated with this label are Adrian Henri, Roger McGough and Brian Patten. -

Strawberry Fields Forever and Sixties Memory Stephen Daniels

Suburban pastoral: Strawberry Fields forever and Sixties memory Stephen Daniels To cite this version: Stephen Daniels. Suburban pastoral: Strawberry Fields forever and Sixties memory. cultural geogra- phies, SAGE Publications, 2006, 13 (1), pp.28-54. 10.1191/1474474005eu349oa. hal-00572170 HAL Id: hal-00572170 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00572170 Submitted on 1 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. cultural geographies 2006 13: 28-54 Suburban pastoral: Stravwberry Fieldsforever and Sixties memory Stephen Daniels School of Geography, University of Nottingham As a cultural period the 1960s is produced through overlapping forms of social memory in which private and public recollections overlap. In both sound and imagery, pop music, particularly that of the Beatles, is a principal medium of memory for the period. For the period from 1965, the progressive aspects of pop music, particularly in sonic and lyrical complexity, expressed a retrospective, pastoral strain that was itself a form of memory of other periods and places, of childhood and country life. The Beatles double-A-sided single Strawberiy Fieldsforever/Penny Lane, released in February 1967, epitomizes these complexities in a suburban version of pastoral, recalling the Liverpool childhoods of songwriters John Lennon and Paul McCartney. -

Roger Mcgough Poet / Author / Performer

Roger McGough Poet / Author / Performer Born in Liverpool, Roger McGough is the author of over fifty books of poetry for both adults and children, as well as editing numerous anthologies. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Emily Talbot [email protected] Publications Poetry Publication Details Notes United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] SAFETY IN NUMBERS This is due for release on the 11th November 2021 2021 'This is not the time for adultery. Viking Your lover will fail to be impressed, not so much by the face mask and stale musk of sanitizing gel, but your flouting of the rules.' At once funny and moving, Safety in Numbers is the new collection from the nation's favourite poet. Traversing new yet timeless terrain with his signature wit and intimacy, Roger McGough brings to life the very strangeness of our times From lost tongues and violins to rising oceans, from adulterers in lockdown to ghosts in line, we may live in dark times and yet find ourselves laughing. From surprising angles and with unexpected voices, McGough, 'a trickster you can trust', reveals the telling moments of our lives. _______________ PRAISE FOR ROGER MCGOUGH 'A witty and ingenious chronicler of British life with a deftness and agility that is hard to beat' Poetry Society 'The patron saint of poetry' Carol Ann Duffy 'McGough has done for poetry what champagne does for weddings' Time Out JOINEDUPWRITING For more than fifty years, Roger McGough has entranced generations of 2019 readers with poetry which is at once playful and poignant, intimate and Penguin ambitious in its scope. -

¶Timglaset #3

¶Timglaset #3. 81 Bobbilott Fika: Innehållsförteckning / Table of Contents Joakim Norling: “proverb: words fly higher than eagles” 37 ¶Timglaset #3. ¶Nonsense is the sixth sense. PROVERB: ¶This issue is dedicated to the absurd, the nonsensical and the grotesque. Jokes and puns as serious artistic endeavour, but also boredom, WORDS FLY HIGHER THAN EAGLES seriousness and earnestness used to absurd or humouristic ends. (BENGT ADLERS Q & A) ¶Some of the inspiration was provided by: Akbar del Piombo Fuzz Against Junk (book), Eric Andersen The Untactis of Music (song), Hugo Ball Karawane (poem), Jacques Carelman Catalogue d’Objets Introuvables (drawings), Ivor Cutler Lemon Flower (song), Bill Domonkos, GIF animations, Bruno Dumont P’tit Quinquin (film), Jean Ferry Traveller with Luggage (story), Robert Filliou Futile Box (artwork), Franquin Black Pages (comic), John Greaves & Peter Blegvad & Lisa Herman Kew. Rhone. (album), ¶Bengt Adlers’ CV is a bit like a history of what Peter Greenaway The Falls (film), Ernst Jandl Tohuwabohu (poem/song), was exciting in art and literature in Malmö from Lyrikvännen 6/2012 Nonsens (magazine issue), Marx Brothers’ mirror the mid-seventies and onward. For fifteen years scene from Duck Soup (film), Francis Picabia Parade Amoureuse (painting), Bengt was the curator at Galerie Leger which Erik Satie A Mammal’s Notebook (writings), Soft Machine A Concise British was internationalist in its approach and in its Alphabet (song), Emmett Williams Duet (spoken word), ZNR Garden Party own way as important for the local art scene as (song). the council-owned Malmö konsthall/art gallery. And during those same years he pursued his own ¶Editor: Joakim Norling vision as an author of experimental, conceptual ¶Design & co-editor: Kolja Ogrumov and humourous books of poetry and stories.