COVID-19): Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices (KAP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report of the Technical Committee Om

REPORT OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS FOR THE APPLICATION OF SHARIA IN KATSINA STATE January 2000 Contents: Volume I: Main Report Chapter One: Preliminary Matters Preamble Terms of Reference Modus Operandi Chapter Two: Consideration of Various Sections of the Constitution in Relation to Application of Sharia A. Section 4(6) B. Section 5(2) C. Section 6(2) D. Section 10 E. Section 38 F. Section 275(1) G. Section 277 Chapter Three: Observations and Recommendations 1. General Observations 2. Specific Recommendations 3. General Recommendations Conclusion Appendix A: List of all the Groups, Associations, Institutions and Individuals Contacted by the Committee Volume II: Verbatim Proceedings Zone 1: Funtua: Funtua, Bakori, Danja, Faskari, Dandume and Sabuwa Zone 2: Malumfashi: Malumfashi, Kafur, Kankara and Musawa Zone 3: Dutsin-Ma: Dutsin-Ma, Danmusa, Batsari, Kurfi and Safana Zone 4: Kankia: Kankia, Ingawa, Kusada and Matazu Zone 5: Daura: Daura, Baure, Zango, Mai’adua and Sandamu Zone 6: Mani: Mani, Mashi, Dutsi and Bindawa Zone 7: Katsina: Katsina, Kaita, Rimi, Jibia, Charanchi and Batagarawa 1 Ostien: Sharia Implementation in Northern Nigeria 1999-2006: A Sourcebook: Supplement to Chapter 2 REPORT OF THE TECHNICAL COMMITTEE ON APPLICATION OF SHARIA IN KATSINA STATE VOLUME I: MAIN REPORT CHAPTER ONE Preamble The Committee was inaugurated on the 20th October, 1999 by His Excellency, the Governor of Katsina State, Alhaji Umaru Musa Yar’adua, at the Council Chambers, Government House. In his inaugural address, the Governor gave four point terms of reference to the Committee. He urged members of the Committee to work towards realising the objectives for which the Committee was set up. -

Monetering of Infectious Diseases in Katsina and Daura Zones of Katsina State: a Clustering Analysis

Available online at http://www.ajol.info/index.php/njbas/index Nigerian Journal of Basic and Applied Science (2011), 19 (1): 31-42 ISSN 0794-5698 Monetering of Infectious Diseases in Katsina and Daura Zones of Katsina State: A Clustering Analysis 1U. Dauda, 2S.U. Gulumbe, *2M. Yakubu and 1L.K. Ibrahim 1Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Umaru Musa Yar’aduwa University, Katsina. 2Department of mathematics Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto Nigeria [*Corresponding Author: [email protected]] ABSTRACT: In this paper, data of infectious diseases were collected from the two senatorial zones of Katsina state, and analyzed using cluster analysis, a multivariate technique. This necessitated a partition of the set of diseases into groups such that the diseases with similar degree of prevalence were identified. The result of the cluster formation shows that Malaria is more prevalent in all of the two zones, followed by Cholera and Typhoid fever using the Single Linkage and Centroid methods. The Complete Linkage and Ward methods showed that Malaria is the most prevalent followed by Typhoid fever and Cholera in Katsina zone, while in Daura zone Typhoid fever is more prevalent followed by Malaria and Cholera. The number of clusters tends to vary from one zone to another. This is achieved by using Chi-square test for independence. The study concludes that the use of clustering methods provides a suitable tool for assessing the level of infections of the disease. Keywords: Cluster analysis, Infectious diseases, Malaria, Cholera and Typhoid INTRODUCTION important is that it is caused by living One of the most challenging tasks to public health microorganisms which can usually be identified, in Nigeria and Africa in general, is the control of thus establishing the aetiology early in the illness. -

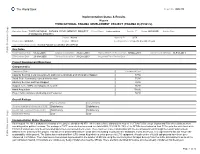

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

IOM Nigeria DTM Flash Report NCNW 37 (31 January 2021)

FLASH REPORT #37: POPULATION DISPLACEMENT DTM North West/North Central Nigeria Nigeria 25 - 31 JANUARY 2021 Casualties: Movement Trigger: 160 Individuals 9 Individuals Armed attacks OVERVIEW The crisis in Nigeria’s North Central and North West zones, which involves long-standing tensions between NIGER REPUBLIC ethnic and religious groups; attacks by criminal Kaita Mashi Mai'adua Jibia groups; and banditry/hirabah (such as kidnapping and Katsina Daura Zango Dutsi Faskari Batagarawa Mani Rimi Safana grand larceny along major highways) led to a fresh Batsari Baure Bindawa wave of population displacement. 134 Kurfi Charanchi Ingawa Sandamu Kusada Dutsin-Ma Kankia Following these events, a rapid assessment was Katsina Matazu conducted by DTM (Displacement Tracking Matrix) Dan Musa Jigawa Musawa field staff between 25 and 31 January 2021, with the Kankara purpose of informing the humanitarian community Malumfashi Katsina Kano Faskari Kafur and government partners in enabling targeted Bakori response. Flash reports utilise direct observation and Funtua Dandume Danja a broad network of key informants to gather represen- Sabuwa tative data and collect information on the number, profile and immediate needs of affected populations. NIGERIA Latest attacks affected 160 individuals, including 14 injuries and 9 fatalities, in Makurdi LGA of Benue State and Faskari LGA of Katsina State. The attacks caused Kaduna people to flee to neighbouring localities. SEX (FIG. 1) Plateau Federal Capital Territory 39% Nasarawa X Affected Population 61% Male Makurdi International border Female 26 State Guma Agatu Benue Makurdi LGA Apa Gwer West Tarka Oturkpo Gwer East Affected LGAs Gboko Ohimini Konshisha Ushongo The map is for illustration purposes only. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

IOM Nigeria DTM Flash Report NCNW 26 June 2020

FLASH REPORT: POPULATION DISPLACEMENT DTM North West/North Central Nigeria. Nigeria 22 - 26 JUNE 2020 Aected Population: Casualties: Movement Trigger: 2,349 Individuals 3 Individuals Armed attacks OVERVIEW Maikwama 219 The crisis in Nigeria’s North Central and North West zones, which involves long-standing Dandume tensions between ethnic and linguis�c groups; a�acks by criminal groups; and banditry/hirabah (such as kidnapping and grand larceny along major highways) led to fresh wave of popula�on displacement. Kaita Mashi Mai'adua Jibia Shinkafi Katsina Daura Zango Dutsi Batagarawa Mani Safana Latest a�acks affected 2,349 individuals, includ- Zurmi Rimi Batsari Baure Maradun Bindawa Kurfi ing 18 injuries and 3 fatali�es, in Dandume LGA Bakura Charanchi Ingawa Jigawa Kaura Namoda Sandamu Katsina Birnin Magaji Kusada Dutsin-Ma Kankia (Katsina) and Bukkuyum LGA (Zamfara) between Talata Mafara Bungudu Matazu Dan Musa 22 - 26 June, 2020. The a�acks caused people to Gusau Zamfara Musawa Gummi Kankara flee to neighboring locali�es. Bukkuyum Anka Tsafe Malumfashi Kano Faskari Kafur Gusau Bakori A rapid assessment was conducted by field staff Maru Funtua Dandume Danja to assess the impact on people and immediate Sabuwa needs. ± GENDER (FIG. 1) Kaduna X Affected PopulationPlateau 42% Kyaram 58% Male State Bukkuyum 2,130 Female Federal Capital Territory LGA Nasarawa Affected LGAs The map is for illustration purposes only. The depiction and use of boundaries, geographic names and related data shown are not warranted to be error free nor do they imply judgment on the legal status of any territory, or any endorsement or accpetance of such boundaries by MOST NEEDED ASSISTANCE (FIG. -

Kabiru Abubakar Gulma

24, Block B, 200 Housing Estate (after Kabiru Abubakar Gulma Kebbi Radio), Birnin Kebbi, Nigeria State Logistics Coordinator [email protected] AXIOS Foundation Nigeria (234) 803 9728 505; (234) 7011558801 Skype ID: mcgulma https://ng.linkedin.com/pub/kabiru- abubakar-gulma/b4/70a/77b S k i l l s : Supply chain management; public health logistics [forecasting, quantification, procurement, Logistics Management Information System (LMIS), and monitoring & evaluation]; contract management; health system strengthening; and project m a n a g e m e n t EDUCATION CAREER EXPERIENCE (3) Euclid University, The Gambia October 2016 to present (July 2016 – Date) Organization: Axios Foundation Nigeria Title/Position: State Logistics Coordinator (Katsina) Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Program: Nigerian Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (Ph.D.) in International Public Programme (MNCH2)- DfID-funded Health Project goals achieved included: (2) Assam Don Bosco University, India (March 2016) 1. Coordinated state-wide review of quantification for 2017 and 2018 commodities Degree: Master of Business and equipment to be supplied to 204 MNCH2- Administration (MBA)- Dual supported health facilities across the 34 Local Degree (Supply Chain and Project Management) Government Areas (LGAs) of Katsina State 2. Supported Katsina State to develop distribution (1) Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria- plans for commodities received in 2015, 2016, Nigeria (August 2010) and 2017 to 16 general hospitals, 29 comprehensive health centers, and 159 Degree: Bachelor of Pharmacy (B. primary health center Pharm) 3. Coordinated the implementation year 3 CERTIFICATE COURSES (1) Johns Hopkins University, MNCH2 renovation of health facilities (14 LGA Baltimore- USA (2017) Medical Stores, 14 LGA Cold Chain Stores, and Course: Statistical Reasoning 9 primary health centers) across Mani, Mashi, for Public Health: Estimation, Daura, Rimi, Bindawa, Zango, Baure, Matazu, Inference, and Interpretation Danmusa, Safana, Kafur, Sabuwa, Kaita, and Danja LGAs. -

First State Integrity Meeting in Katsina

First State Integrity Meeting in Katsina Edited and co-auhtored by; Petter Langseth and Oliver Stolpe UNODC’s Global Programme against Corruption Katsina, 18-19 June 2003 Disclaimer The views expressed herein are those of the authors and editors and not necessarily those of the United Nations 2 TABLE OF CONTENT I. FOREWORD............................................................................................................... 4 II. OVERVIEW................................................................................................................. 5 A. Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5 B. Origins of the initiative.............................................................................................. 5 C. The way forward in Nigeria ....................................................................................... 6 D. The First Judicial Integrity Meeting.......................................................................... 6 E. Follow-up action identified in the course of the Workshop....................................... 7 III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY......................................................................................... 10 A. The State Integrity Meeting...................................................................................... 10 B. Conclusions and Recommendations ....................................................................... 10 C. Katsina State. Summary Anti Corruption Action Plan ........................................... -

2018/2019 Annual School Census Report

Foreword Successful education policies are formed and supported by accurate, timely and reliable data, to improve governance practices, enhance accountability and ultimately improve the teaching and learning process in schools. Considering the importance of robust data collection, the Planning, Research and Statistics (PRS) Department, Katsina State Ministry of Education prepares and publishes the Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of both Public and Private Schools on an annual basis. This is in compliance with the National EMIS Policy and its implementation. The Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of 2018-2019 is the outcome of the exercise conducted between May and June 2019, through a rigorous activities that include training Head Teachers and Teachers on School Records Keeping; how to fill ASC questionnaire using school records; data collection, validation, entry, consistency checks and analysis. This publication is the 13th Annual Schools Census Statistical Report of all Schools in the State. In line with specific objectives of National Education Management Information System (NEMIS), this year’s ASC has obtained comprehensive and reliable data where by all data obtained were from the primary source (the school’s head provide all data required from schools records). Data on Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) of basic education and post basic to track the achievement of the State Education Sector Operational Plan (SESOP) as well as Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); feed data into the National databank to strengthen NEMIS for national and global reporting. The report comprises of educational data pertaining to all level both public and private schools ranging from pre-primary, primary, junior secondary and senior secondary level. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT FEBRUARY 13, 2019 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Nkwor Market Square, Adazi- Enu, Anaocha Local Govt, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 16 Adazi-Nnukwu Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Near Eke Market, Adazi Nnukwu, Adazi, Anambra State ANAMBRA 17 Addosser Microfinance Bank Limited State 32, Lewis Street, Lagos Island, Lagos State LAGOS 18 Adeyemi College Staff Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Adeyemi College of Education Staff Ni 1, CMS Ltd Secretariat, Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo ONDO 19 Afekhafe Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit No. -

2Nd-Admission-List-CSE-2021.Pdf

DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SOFTWARE ENGINEERING SECOND ADMISSION LIST 2020/2021 ACADEMIC SESSION S/N NAME JAMB NO LG STATE REMARK 1 ZAKARI SANI 21109851CA KANKIA KATSINA 2 ABDULLAHI USMAN 21108346EA BATAGARAWA KATSINA 3 NURADDEEN SHAFI'U ABDULLAHI 21118540IF KATSINA KATSINA 4 MU'AZU IBRAHIM GAFAI 21008910IF KATSINA KATSINA 5 MUKHTAR AMMAR 21021462CF KATSINA KATSINA 6 NURA IBRAHIM SHU'AIBU 21114941DA KATSINA KATSINA 7 USMAN MUHAMMAD 21124251DA KATSINA KATSINA 8 ABDULRAHIM IMRANA 21134389HA KATSINA KATSINA 9 ABDULLAHI NASIR 21108913FF KATSINA 10 ABDULLAHI USMAN 21108346EA RIMI KATSINA 11 ABDULKADIR YUSUF 21116697IF KURFI KATSINA 12 KABIR SURAJO 21124632CF RIMI KATSINA 13 HUSSAINI ALAMIN DANHAIRE 21125594GA MUSAWA KATSINA 14 USMAN SULAIMAN BALA 21109826FA FASKARI KATSINA 15 KHADIJA IBRAHIM 21110114DF MALUMFASHI KATSINA 16 DAHIRU ABUBAKAR TANKURI 21113099CF JIBIA KATSINA 17 HUSSAINI ABBAS ADAMU 21115778CF MATAZU KATSINA 18 AHMAD ARAFAT 21108787CA RIMI KATSINA 19 SANI ABDULLAHI HALLIRU 21109304JF KANKARA KATSINA 20 ABUBAKAR ABDULRASHID 21106628IA JIBIA KATSINA 21 BABANGIDA MU'AZU ALMUSTAPHA 21108659JA KATSINA KATSINA 22 MUSA SALAHUDDEEN 21109378BA BAKORI KATSINA 23 ZAINAB IMAM MUHAMMAD 21128654FF KANKIA KATSINA 24 IDRIS ABDULLAHI 21109387GA MATAZU KATSINA 25 DAHIRU IS'HAQ 21136785GA KATSINA KATSINA 26 DAHIRU ABUBAKAR RAFUKKA 21107101JA KATSINA KATSINA 27 AMINU IBRAHIM 21108454HA KATSINA KATSINA 28 IBRAHIM FATIMA 21118613AF KATSINA KATSINA 29 BISHIR YSUF SHEHU 21115880IF KATSINA KATSINA 30 TANIMU ABDULGANIYU HASSAN 22198263DF RIMI KATSINA 31 ABBAS