Politics and Society in Plautus' "Trinummus"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. Fighting Corruption: Political Thought and Practice in the Late Roman Republic

2. Fighting Corruption: Political Thought and Practice in the Late Roman Republic Valentina Arena, University College London Introduction According to ancient Roman authors, the Roman Republic fell because of its moral corruption.i Corruption, corruptio in Latin, indicated in its most general connotation the damage and consequent disruption of shared values and practices, which, amongst other facets, could take the form of crimes, such as ambitus (bribery), peculatus (theft of public funds) and res repentundae (maladministration of provinces). To counteract such a state of affairs, the Romans of the late Republic enacted three main categories of anticorruption measures: first, they attempted to reform the censorship instituted in the fifth century as the supervisory body of public morality (cura morum); secondly, they enacted a number of preventive as well as punitive measures;ii and thirdly, they debated and, at times, implemented reforms concerning the senate, the jury courts and the popular assemblies, the proper functioning of which they thought might arrest and reverse the process of corruption and the moral and political decline of their commonwealth. Modern studies concerned with Roman anticorruption measures have traditionally focused either on a specific set of laws, such as the leges de ambitu, or on the moralistic discourse in which they are embedded. Even studies that adopt a holistic approach to this subject are premised on a distinction between the actual measures the Romans put in place to address the problem of corruption and the moral discourse in which they are embedded.iii What these works tend to share is a suspicious attitude towards Roman moralistic discourse on corruption which, they posit, obfuscates the issue at stake and has acted as a hindrance to the eradication of this phenomenon.iv Roman analysis of its moral decline was not only the song of the traditional laudator temporis acti, but rather, I claim, included, alongside traditional literary topoi, also themes of central preoccupation to Classical political thought. -

Girls, Girls, Girls the Prostitute in Roman New Comedy and the Pro

Xavier University Exhibit Honors Bachelor of Arts Undergraduate 2016-4 Girls, Girls, Girls The rP ostitute in Roman New Comedy and the Pro Caelio Nicholas R. Jannazo Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH Follow this and additional works at: http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Jannazo, Nicholas R., "Girls, Girls, Girls The rP ostitute in Roman New Comedy and the Pro Caelio" (2016). Honors Bachelor of Arts. Paper 16. http://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/hab/16 This Capstone/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate at Exhibit. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Bachelor of Arts by an authorized administrator of Exhibit. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Xavier University Girls, Girls, Girls The Prostitute in Roman New Comedy and the Pro Caelio Nick Jannazo CLAS 399-01H Dr. Hogue Jannazo 0 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................................2 Chapter 1: The meretrix in Plautus ..................................................................................................7 Chapter 2: The meretrix in Terence ...............................................................................................15 Chapter 3: Context of Pro Caelio -

Amphitryon from Plautus to Gib.Audoux Lia

.AMPHITRYON FROM PLAUTUS TO GIB.AUDOUX LIA STAICOPOULOU '• Master of Science Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College Stilhrater, Oklahoma 1951 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the Oklahoma Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Mey, 1953 ii fflO~!OMA AGRICDLTURAL & t:

PONTEM INTERRUMPERE: Plautus' CASINA and Absent

Giuseppe pezzini PONTEM INTERRUMPERE : pLAuTus’ CASINA AnD ABsenT CHARACTeRs in ROMAn COMeDY inTRODuCTiOn This article offers an investigation of an important aspect of dramatic technique in the plays of plautus and Terence, that is the act of making reference to characters who are not present on stage for the purpose of plot, scene and theme development (‘absent characters’). This kind of technique has long been an object of research for scholars of theatre, especially because of the thematization of its dramatic potential in the works of modern playwrights (such as strindberg, ibsen, and Beckett, among many others). extensive research, both theoretical and technical, has been carried out on several theatrical genres, and especially on 20 th -century American drama 1. Ancient Greek tragedy has recently received attention in this respect also 2. Less work has been done, however, on another important founding genre of western theatre, the Roman comedy of plautus and Terence, a gap due partly to the general neglect of the genre in the second half of the 20 th century, in both scholarship and reception (with some important exceptions). This article contributes to this area of theatre research by pre - senting an overview of four prototypical functions of ‘absent characters’ in Roman comedy (‘desired’, ‘impersonated’, ‘licensing’ and ‘proxied’ absentees), along with a discussion of their metatheatrical potential and their close connection archetypal in - gredients of (Roman) comedy. i shall begin with a dive into plautus’ Casina ; this play features all of what i shall identify as the ‘prototypes’ of absent characters in comedy, which will be discussed in the first part of this article (sections 1-5). -

Pro Filia, Pro Uxore: Young Women in the Conventional and Unconventional Families of Roman Comedy

PRO FILIA, PRO UXORE: YOUNG WOMEN IN THE CONVENTIONAL AND UNCONVENTIONAL FAMILIES OF ROMAN COMEDY Hannah Sorscher A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Classics Department. Chapel Hill 2021 Approved by: Sharon L. James David Konstan Dorota Dutsch Amy Richlin Alexander Duncan ©2021 Hannah Sorscher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Hannah Sorscher: Pro filia, pro uxore: Young Woman in the Conventional and Unconventional Families of Roman Comedy (Under the direction of Sharon L. James) In this dissertation, I explore both the diverse variability and the traditional ideologies of the Roman family in the powerfully relevant medium of Roman comedy, with a particular focus on how different types of families in the genre treat young women. Plautus and Terence reinvented their dramatic form to depict families that would be recognizable, meaningful, and resonant for their audiences in Rome and Italy of the 200s–160s BCE. These playwrights show an expanded definition of family beyond the familiar citizen form repeatedly presented in later evidence. Around the citizen families that are the focus of the genre, they stage families of choice created by marginalized people (lower-class women and foreign soldiers in particular). In Plautus’ and Terence’s plays, I identify tWo patterns: (1) a critique of the legal and social institutions that governed citizen family life in Rome of their day and (2) a counter- staging, as it were, of alternate models of families that contrast sharply with the citizen family in their structures, members, and priorities. -

Loeb Classical Library Philo

Loeb classical library philo Continue Want more? Advanced embedding details, examples and help! This article needs additional quotes to verify. Please help improve this article by adding quotes to reliable sources. Non-sources of materials can be challenged and removed. Find sources: Classical Library - News newspaper book scientist JSTOR (January 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Volume 170N Greek Collection in the classical library Loeb, revised edition of Volume 6 Latin Collection in the classical library of Loeb, second edition of the 1988 Classical Library (LCL; Named after James Lebe; /loʊb/, German: løːp) is a series of books originally published by Heinemann in London, United Kingdom, today by Harvard University Press, USA, which presents important works of ancient Greek and Latin literature in a way that makes the text accessible to the widest possible audience, presenting the original Greek or Latin text on each left page, and a rather literal translation on the main page. The editor-in-chief is Jeffrey Henderson, a William Goodwin Aurelio professor of Greek language and literature at Boston University. The history of the Classic Library of Loeb was conceived and originally funded by Jewish-German-American banker and philanthropist James Loeb (1867-1933). The first volumes were edited by Thomas Ethelbert Page, W. H. D. Rouse and Edward Capps and published by William Hinemann (London) in 1912, already in their distinctive (green for Greek text) and red (for Latin) hardcover bindings. Since then, dozens of new titles have been added, and the earliest translations have been revised several times. In recent years this has included the removal of bowdlerization from previous editions, which often reversed the sex of subjects of romantic interest to hide homosexual references or (in the case of early editions of Daphnis Longus and Chloe) translated sexually explicit excerpts from ancient Greek into Latin rather than English. -

The Author of the Greek Original of the 'Poenulus

252 T. 'A. D 0 r e y: The elections oE 216 B~C. Aemilius's dying message to'Fabius, stories, which need not·be tota]ly rejected as apocryphaI 12), but alsoby the family con- riection with t:heFabii established by his son. " If this is so, the election of Aemilius Paulus will represent a compromise between tbe Scipionicgroup and the Fabii, under which Fabius withdrewhis threat to invalidate the elections in ,return for the' election of one consul' wno, though a leading member of the Scipionic group, was personally acceptable to hirn. Birmingham T. A. Dorer THE AUTHOR OF THE GREEK ORIGINAL OF THE 'POENULUS ".: - . '" .. , Adequate analysis ofall the theories thathave, like barnacles, attached themselves to that',rather poor Plautine play, the Poenulus; woul<! require a volume of gargantuan size. The aim of this essay is modest:" to track down finallythe atithor of the Greek original used by Plautus as, his main source; con seqUently the larger questions, dealing with the methods of Plautus in adapting his Greek originals, will here be cOrisidered only insofar as they become relevant to mymain thesis. This 'is, that Alexis' 'Karchedonios' lies behind Plautus' play; the theoryhaspreviously been propounded byBergk1) andothers, • a,nd it is ön the foundation of theirpositive if uncertain argu- ' ments thatI desire to build here: It' is hoped that the resulting edifice will then be able to stand firm and stormproOf. ', Dietze first rested this theory ona firm fö~ndation, when he pointed out in a dissertation 2) that the one remaining frag- , men,t ofAlexis' 'Karchedonios'(Kock,.CAF II 331, 100): ßax'Yj• Aoe; , Er, appears to be translated at PoerlUlus 1318: Nam te, " , ,',' 12) The' story oE the death oE Aemilius 'in LivyXXII. -

Plautus, with an English Translation by Paul Nixon

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY fT. E. PAGE, C.H., LTTT.D. t E. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. t W. H, D. ROUSE, litt.d. L. A. POST, M.A. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., r.B.HisT.soc. PLAUTUS V P L A U T U S WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY PAUL NIXON DKAK OF BOWDOIN OOLUKGK, XAIKS IN FIVE VOLUMES V SnCHUS THREE BOB DAY TRUCULENTUS THE TALE OF A TRAVELLING BAG FRAGMENTS .#e LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MCMLII First printed 193S Reprinted 1952 Pfl T Printed in Great Britain THE GREEK ORIGINALS AND DATES OF THE PLAYS IN THE FIFTH VOLUME The Stichus was adapted from Menander's 'A8*A^oi, a second 'A3eA<^oi, and was presented at Rome in A.D. 200. The date of presentation of its original is less certain. The combined facts that the brothers had been able to enjoy three years of apparently peaceful ^ trading in Asia, that the people of Am- bracia had envoys \isiting Athens,^ that Pinacium intends to make things unpleasant for any " king " ^ who blocks his path and expects such an impressive * welcome from his mistress, lead Hueffner ^ to believe that the 'ABe\(f>oi was produced in 306 b.c. when Demetrius Poliorcetes wintered at Athens with much pomp and circumstance. References in the Trinummus to Asian trade and war,® and to busybodies knowing quid in aurem rex reginae dixerit ' cause Hueffner ® to assign its Greek original, Philemon's ©T^cravpos, to the period when this same Demetrius Poliorcetes ruled in Athens, 292-287 B.C. -

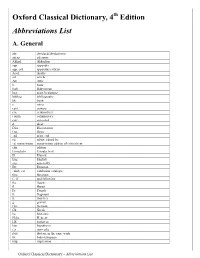

Abbreviations List A

Oxford Classical Dictionary, 4th Edition Abbreviations List A. General abr. abridged/abridgement adesp. adespota Akkad. Akkadian app. appendix app. crit. apparatus criticus Aeol. Aeolic art. article Att. Attic b. born Bab. Babylonian beg. at/nr. beginning bibliog. bibliography bk. book c. circa cent. century cm. centimetre/s comm. commentary corr. corrected d. died Diss. Dissertation Dor. Doric end at/nr. end ed. editor, edited by ed. maior/minor major/minor edition of critical text edn. edition Einzelschr. Einzelschrift El. Elamite Eng. English esp. especially Etr. Etruscan exhib. cat. exhibition catalogue fem. feminine f., ff. and following fig. figure fl. floruit Fr. French fr. fragment ft. foot/feet g. gram/s Ger. German Gk. Greek ha. hectare/s Hebr. Hebrew HS sesterces hyp. hypothesis i.a. inter alia ibid. ibidem, in the same work IE Indo-European imp. impression Oxford Classical Dictionary – Abbreviations List in. inch/es introd. introduction Ion. Ionic It. Italian kg. kilogram/s km. kilometre/s lb. pound/s l., ll. line, lines lit. literally lt. litre/s L. Linnaeus Lat. Latin m. metre/s masc. masculine mi. mile/s ml. millilitre/s mod. modern MS(S) manuscript(s) Mt. Mount n., nn. note, notes n.d. no date neut. neuter no. number ns new series NT New Testament OE Old English Ol. Olympiad ON Old Norse OP Old Persian orig. original (e.g. Ger./Fr. orig. [edn.]) OT Old Testament oz. ounce/s p.a. per annum PIE Proto-Indo-European pl. plate plur. plural pref. preface Proc. Proceedings prol. prologue ps.- pseudo- Pt. part ref. reference repr. -

Elise Larres LAT 530 Dr. Christenson PLAUTUS AS TRANSLATOR The

Elise Larres LAT 530 Dr. Christenson PLAUTUS AS TRANSLATOR The Roman Translation Project • Widescale adoption/translation of Greek literature into Latin • 240 BCE – first Roman play by Livius Andronicus, based on Greek model(s) • aemulatio (rivaling the ST) Plautus and early Roman drama • Prologues of Plautus and Terence = first explicit reference to translation in Rome (McElduff 2013: 62). • 6 prologues of Plautus directly mention a Greek source text (Asinaria, Casina, Mercator, Miles Gloriosus, Poenulus, and Trinummus) • vortit barbare • Hellenocentric • Authenticating force (Handley 1975: 119) • Playwrights parading Greek source texts = literary equivalent of triumphing generals who parade their foreign spoils (Connors 2004: 204) Plautus and His Source Text • We do not have the Greek source texts for much of Plautus’ work. • Menander papyrus discovered containing fragments of the Dis Exapaton, Plautus’ ST for the Bacchides. Comparing the Texts ἀρνήσεται μέν, οὐκ [ἄ]δηλόν ἐστί μοι— ἰταμὴ γάρ—εἰς μέσον τε π[ά]ντες οἱ θεοὶ ἥξουσι. μὴ τοίνυν [.]ον[. .] νὴ Δία. κακὴ κακῶς τοίνυν—ἐ[π]άν[αγε, Σ]ώστρατε· ἴσως σε πείσει· δοῦλο[ς . .]ρα[. (20–24) Oh, she’ll deny it, that much is clear to me. For she’s bold, and all the gods have come into the middle (called by her oaths). (suddenly acting as Chrysis) “Well then, I hope it does me no good at all!” (as himself again, angrily responding) (Ha! It won’t,) by Zeus! (Chrysis-voice) “Then let me, wretched, (die) wretchedly!” (as himself again, to himself) [wait,] Sostratus: maybe she’ll persuade you— (Chrysis-voice) “So you’re here as your father’s slave?” ne illa illud hercle cum malo fecit . -

Introducing Geminate Writing: Plautus' Miles Gloriosus

Vasiliki Kella Introducing geminate writing: Plautus’ Miles Gloriosus Abstract The purpose of this paper is to examine how the theme of the Double is presented in Plautus’ Miles Gloriosus . Underneath the obvious relation between the doubling and comedies like Miles Gloriosus , there is something more systematic about this method that deserves to be explored. ‘Geminate writing’ acquires a multileveled dynamics in Plautus’ comic language, characters, plot and performance. We discuss the expression hoc argumentum sicilicissitat which is proved to denote the gemination of plots and characters. We are then led to see the gemination of staging. The device of doubles and twins and the story of a dream cause the stage to split into two mirroring halves. We focus on the skenographia and we see the temporary stage and its structure, the physical format of which creates mirror reflections. The paper is divided into three parts, covering the textual, theatrical and performance levels of Miles Gloriosus , respectively. Lo scopo di questo studio è quello di esaminare il modo in cui viene presentato il tema del doppio nel Miles Gloriosus di Plauto. Sotto la relazione evidente tra il raddoppio e commedie come il Miles Gloriosus , c'è qualcosa di più sistematico in questo metodo che merita di essere esplorato. ‘Geminate writing’ riguarda dinamiche multilivello su linguaggio, personaggi e intreccio comico di Plauto. Viene presa in esame la frase hoc argumentum sicilicissitat che indica la duplicazione di trame e personaggi. In seguito viene analizzata la duplicazione di scena. Il dispositivo di doppio e la storia di un sogno dividono infatti la scena stessa in due metà speculari. -

Terence's Meretrices in the New Comic Tradition My Decision to Limit

Chapter 1: Terence’s Meretrices in the New Comic Tradition My decision to limit this analysis of the speech of New Comedy meretrices to the plays of Terence is based upon a distinction between the meretrices of Plautus and those of Terence. The two playwrights’ treatments of this stock character type differ by giving the meretrices dif- ferent roles to play in resolving the citizen-based plots of their plays. While Plautine meretrices typically pursue their own interests more attentively than those of citizen families, thus adhering to stereotypes about the meretrix stock type, Terentian meretrices promote the success of citizen families or individual family members whenever the plot places citizens in precarious positions. Plautus and Terence have different degrees of interest in citizens: Plautus foregrounds the non- citizen characters such as slaves, while Terence devotes more time to citizen families. The dis- tinction between meretrices who are interested and uninterested in citizen families corresponds to the differing degrees of interest that Terence and Plautus take in the citizen-based plots of their plays. Most New Comedies involve more than one plot or subplot, and those plots do not all concern the families and social values of citizens. Many plays include a romantic plot involving the attempts of young people to marry or to carry on a relationship outside marriage. In many, the servus callidus is the hero, and his tricks and schemes entertain the audience. These two plot- Mazzara 2 types often coexist within a play and depend upon each other.1 A third element in the plays is a plot that involves some form of threat to the citizen family.