The Moods of Sarajevo. Excerpts from the Diary of an Observer Ed Van Thijn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vastgeroeste Idealen

Bachelorscriptie Geschiedenis VASTGEROESTE IDEALEN De Communistische Partij Nederland, de verandering van haar politieke oriëntatie en de doorwerking daarvan op de Binnenlandse Veiligheidsdienst (1945 -1991) Auteur: Kort, J.W.J. de (Jasper) Studentnummer: S4344219 Begeleider: dr. M.H.C.H. Leenders Nijmegen, 18 oktober 2018 1 Inhoudsopgave Inleiding..................................................................................................................................... 3 Hoofdstuk 1: Vijandbeelden: ontstaan, verandering en functie .......................................... 6 Vijand en vijandbeeld ............................................................................................................. 6 Hoe ontstaan vijandbeelden? .................................................................................................. 7 Wat is de functie van vijandbeelden? ..................................................................................... 7 Hoe veranderen vijandbeelden? ............................................................................................. 8 Het communistisch vijandbeeld in Nederland ....................................................................... 8 Hoofdstuk 2: Einthovens BVD .............................................................................................. 10 Einthovens anticommunisme ............................................................................................... 10 Een dienst naar Einthovens richtlijnen ................................................................................ -

Verloren Vertrouwen

ANNE BOs Verloren vertrouwen Afgetreden ministers en staatssecretarissen 1967-2002 Boom – Amsterdam Verloren vertrouwen Afgetreden ministers en staatssecretarissen 1967-2002 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens het besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 28 maart 2018 om 14.30 uur precies door Anne Sarah Bos geboren op 25 februari 1977 te Gouda INHOUD INLEIdINg 13 Vraagstelling en benadering 14 Periodisering en afbakening 20 Bronnen 22 Opbouw 23 dEEL I gEïsOLEERd gERAAkT. AftredEN vanwegE EEN cONfLIcT IN hET kABINET 27 hOOfdsTUk 1 dE val van mINIsTER dE Block, ‘hET mEEsT gEgEsELdE werkpAARd’ VAN hET kABINET-dE JONg (1970) 29 ‘Koop prijsbewust, betaal niet klakkeloos te veel’ 32 ‘Prijzenminister’ De Block op het rooster van de oppositie 34 Ondanks prijsstop een motie van wantrouwen 37 ‘Voelt u zich een zwak minister?’ 41 De kwestie-Verolme: een zinkend scheepsbouwconcern 43 De fusie-motie: De Block ‘zwaar gegriefd’ 45 De Loonwet en de cao-grootmetaal 48 Tot slot. ‘Ik was geen “grote” figuur in de ministerraad’ 53 hOOfdsTUk 2 hET AftredEN van ‘IJzEREN AdRIAAN’ van Es, staatssEcretaris van dEfENsIE (1972) 57 De indeling van de krijgsmacht. Horizontaal of verticaal? 58 Minister De Koster en de commissie-Van Rijckevorsel 59 Van Es stapt op 62 Tot slot. Een rechtlijnige militair tegenover een flexibele zakenman 67 hOOfdsTUk 3 sTAATssEcretaris JAN GlasTRA van LOON EN dE VUILE was Op JUsTITIE (1975) 69 Met Mulder, de ‘ijzeren kanselier’, op Justitie 71 ‘Ik knap de vuile was op van anderen’ 73 Gepolariseerde reacties 79 In vergelijkbare gevallen gelijk behandelen? Vredeling en Glastra van Loon 82 Tot slot. -

De Liberale Opmars

ANDRÉ VERMEULEN Boom DE LIBERALE OPMARS André Vermeulen DE LIBERALE OPMARS 65 jaar v v d in de Tweede Kamer Boom Amsterdam De uitgever heeft getracht alle rechthebbenden van de illustraties te ach terhalen. Mocht u desondanks menen dat uw rechten niet zijn gehonoreerd, dan kunt u contact opnemen met Uitgeverij Boom. Behoudens de in of krachtens de Auteurswet van 1912 gestelde uitzonde ringen mag niets uit deze uitgave worden verveelvoudigd, opgeslagen in een geautomatiseerd gegevensbestand, of openbaar gemaakt, in enige vorm of op enige wijze, hetzij elektronisch, mechanisch door fotokopieën, opnamen of enig andere manier, zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. No part ofthis book may be reproduced in any way whatsoever without the writtetj permission of the publisher. © 2013 André Vermeulen Omslag: Robin Stam Binnenwerk: Zeno isbn 978 90 895 3264 o nur 680 www. uitgeverij boom .nl INHOUD Vooraf 7 Het begin: 1948-1963 9 2 Groei en bloei: 1963-1982 55 3 Trammelant en terugval: 1982-1990 139 4 De gouden jaren: 1990-2002 209 5 Met vallen en opstaan terug naar de top: 2002-2013 De fractievoorzitters 319 Gesproken bronnen 321 Geraadpleegde literatuur 325 Namenregister 327 VOORAF e meeste mensen vinden politiek saai. De geschiedenis van een politieke partij moet dan wel helemaal slaapverwekkend zijn. Wie de politiek een beetje volgt, weet wel beter. Toch zijn veel boeken die politiek als onderwerp hebben inderdaad saai om te lezen. Uitgangspunt bij het boek dat u nu in handen hebt, was om de geschiedenis van de WD-fractie in de Tweede Kamer zodanig op te schrijven, dat het trekjes van een politieke thriller krijgt. -

De Parallelle Levens Van Hans En Hans

De parallelle levens van Hans en Hans Door Roelof Bouwman - 16 januari 2021 Geplaatst in Boeken Het is nog maar nauwelijks voorstelbaar, maar tot ver in de jaren negentig van de vorige eeuw verschenen in Nederland nauwelijks biografieën. Terwijl je in Britse, Amerikaanse, Duitse en Franse boekwinkels struikelde over de vuistdikke levensbeschrijvingen van historische kopstukken als Winston Churchill, John F. Kennedy, Konrad Adenauer en Charles de Gaulle, hadden Nederlandse historici nauwelijks belangstelling voor het biografische genre. Over de meeste grote vaderlanders – van Johan Rudolf Thorbecke tot Multatuli, van Anton Philips tot Aletta Jacobs en van koningin Wilhelmina tot Joseph Luns – bestond geen enkel fatsoenlijk boek. Het verloop van de geschiedenis, zo hoorde je Nederlandse historici vaak beweren, wordt niet bepaald door personen, maar door processen: industrialisatie, (de)kolonisatie, verzuiling, democratisering, emancipatie, enzovoorts. Daarnaast werd de weerzin tegen biografieën gevoed door de protestantse angst – in Nederland wijdverbreid – voor het ‘ophemelen’ van individuen. Van feministische zijde kwam daar nog de afkeer bij tegen geschiedschrijving met ‘grote mannen’ in de hoofdrol. Al met al een dodelijke cocktail. Maar nu: een tsunami van biografieën Inmiddels is alles anders. Het anti-biografische klimaat is de afgelopen vijfentwintig jaar dermate drastisch omgeslagen dat het bijvoorbeeld moeilijk is geworden om een prominente, twintigste-eeuwse Wynia's week: De parallelle levens van Hans en Hans | 1 De parallelle levens van Hans en Hans politicus te noemen wiens leven nog níet is geboekstaafd. De oud-premiers Abraham Kuyper, Dirk Jan de Geer en Joop den Uyl maar ook VVD-boegbeeld Neelie Kroes en D66-prominent Hans Gruijters kregen zelfs twee keer een biografie. -

RUG/DNPP/Repository Boeken/De Stranding/11. De Stranding

227 HOOFDSTUK II De stranding Hoe het CDA de verkiezingen, de macht en de kroonprins verloor Diep in de nacht van donderdag 7 op vrijdag 8 april loopt Frits Wester in de wandelgangen van de Tweede Kamer zijn collega Jan Schinkelshoek tegen het lijf. Zijn voormalige baas, nu pers- voorlichter van minister Hirsch Baum, heeft een vraag. 'Waar benje morgen?' 'Thuis', antwoordt Wester. Op vrijdag verga- dert de Kamer niet, en hij wil een vrije ochtend nemen. 'Houje maar liever beschikbaar', zegt Schinkelshoek. 'Er staat misschien iets vervelends te gebeuren; ik kanje alleen niet vertellen wat.' Het is geen toeval dat de twee voorlichters op dat tijdstip nog in de Kamer zijn. Vanaf twee uur 's middags heeft het parlement gedebatteerd over de IRT-zaak, waarbij zowel Hirsch Ballin als minister Van Thijn zware kritiek te verduren kregen. In de loop van de avond is een motie van afkeuring ingediend tegen Hirsch BalEn. Hij is als minister vanjustitie medeverantwoordelijkvoor de falende controle op het Interregionale Recherche Team, waarover inj anuari nogal wat commotie ontstond. Het is nu drie uur. Zojuist heeft de Kamer die motie verworpen. De CDA-frac- tie heeft serieus overwogen haar te steunen en Hirsch Ballin te laten vallen, maar heeft daar op het laatste moment van afgezien. Wel komt er een parlementair onderzoek naar de opsporingsme- thoden die de recherche gebruikt in de strijd tegen de zware mis- daad, omdat er ernstige twijfel is gerezen over de toelaatbaarheid daarvan. Toen Hirsch BalEn en Van Thijn twee weken eerder, Op zi maart, een onderzoeksrapport over de IRT-zaak ontvin- gen, was meteen al duidelijk dat deze zaak ernstige politieke con- sequenties kon hebben. -

Burgemeestersblad Nr 51

burgemeestersblad nederlands genootschap van burgemeesters jaargang 14, februari 2009 51 • • Nationale Ombudsman Alex Brenninkmeijer • Sterke colleges • Gouda na het busincident Optimisme, nihilisme en extreem gedrag multiculturele samenleving uitsluitend van onze tijd is. boekbespreking Ook constateert hij dat de verdraagzaamheid in de loop der eeuwen, alle hedendaagse discussie ten spijt, is toegenomen. Het overgrote gedeelte van de mensen in ons land is gematigd en redelijk. In de beeldvorming krijgt geweld, door de voortdurende uitvergroting en herhaling, bovenmatig aandacht. In dit licht is Hooger- werf optimistisch. Nihilisme Een van zijn centrale thema’s in zijn verhandeling is het verschijnsel van het nihilisme. Door allerlei culturele en structurele ontwikkelingen is er een nihilistische mens ontstaan met afwezigheid van hogere waarden, hedonis- tisch gedrag, oppervlakkigheid, het gevoel er niet bij te horen, gebrek aan verdraagzaamheid en weinig vertrou- wen in anderen en in de overheid. Er is sprake van een groeiende sociale ontbinding die de mens terugwerpt in primitieve sferen van individualisme. In dit verband gaat Hoogerwerf ook uitgebreid in op bepaalde uitwassen van het moderne kapitalisme. Aanknopingspunten voor verstandig overheidsbeleid vindt Hoogerwerf onder meer in datgene dat de Neder- lander in de loop der eeuwen heeft gekenmerkt: ver- Extreem gedrag. Het openbaart zich, ook in Neder- draagzaamheid. Zonder het zo te noemen raakt hij daar- land. Andries Hoogerwerf, oud-hoogleraar Bestuurs- mee onmiskenbaar de door velen gezochte nationale kunde van de Universiteit Twente, schreef er een boek identiteit. Hij bespreekt mogelijkheden tot de herwaar- over. In De donkere onderstroom gaat hij in op de dering van zingeving en put daarbij inspiratie uit onder achtergronden ervan en zoekt richtingen die politici meer drie grote religies en het humanisme, die alle pleit- en bestuurders kunnen inslaan om extreem gedrag te voerders zijn voor verdraagzaamheid en naastenliefde. -

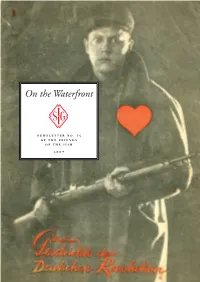

On the Waterfront 5 1

{ 1 } INTERNATIONAAL INSTITUUT VOOR SOCIALE GESCHIEDENIS INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL HISTORY On the Waterfront the On n e w s l e t t e r n o . 1 5 of the friends of the iish 2 0 0 7 on the waterfront 15 · 2007 on the waterfront 15 · 2007 Introduction f r o n t p a g e : The highlight of this issue may be the report of the meeting on 21 June, which after all was initi- f r o n t c o v e r ated by Gilles Borrie, one of our original Friends. His tremendous involvement in the Partij van de o f t h e Arbeid (PvdA, the Social Democratic Party of the Netherlands) politics, combined with his schol- I l l u s t r i e r t e arly-historical interest in this subject, led him to suggest the history of local social democracy as Ge s c h i c h t e the subject for this day. It has been elaborated here for the Netherlands and for Amsterdam in par- d e r d e u t - ticular, although the Dutch experiences undoubtedly have a far broader validity. We hope that our s c h e n r e v o - foreign friends and readers will identify with the stories of prominent PvdA officials, such as Gilles l u t i o n , s e e Borrie (who served as mayor of Eindhoven, in addition to other offices) and Ed van Thijn (who was p a g e 6 mayor of Amsterdam and later a minister in the Dutch government). -

Western Europe

Western Europe Great Britain National Affairs J. HE GOVERNMENT SHOWED surprising stability in 1985, despite the continuing economic slowdown, labor difficulties, and growing racial unrest. The strike by the National Union of Mineworkers, which had begun in March 1984, ended a year later with the workers agreeing to accept reduced terms and the government going ahead with its program of pit closures. Another indicator of weakening trade-union strength was an abortive strike in August by the National Union of Railwaymen, whose protest failed to halt the introduction of driver-only trains. Elsewhere on the labor front, a breakdown in teachers' pay talks in February was followed in July by strikes, which continued with growing intensity during the autumn. Unemployment in Britain remained at around 3.4 million during the year, some 14 percent of the labor force. On the economic front, the year began with the pound at a record low of $1.1587. When it plunged to below $1.10 in February, interest rates were raised from 12 to 14 percent, which helped stem the decline. Racism and Anti-Semitism Racial and social tensions in British society erupted in violence on several occa- sions during the year. In September police in riot gear battled black youths in Handsworth (Birmingham) and Brixton (London); in October a policeman was stabbed to death in an outbreak in Tottenham in which, for the first time, rioters fired shots at police. The number of police and civilians injured in riots during the year reached 254. Right-wing National Front (NF) members were increasingly implicated in vio- lence at soccer matches. -

Carambole! Johan Van Merriënboer

Jaarboek Parlementaire Geschiedenis 1999 Carambole! De nacht van Wiegel in de parlementaire geschiedenis Johan van Merriënboer Wat doet een biljarter wanneer hij de pot kan uitmaken met een simpele stoot? Zijn tegen- stander heeft de ballen klaargelegd in een driehoekje, luid roepend: ‘Jij mag helemaal niet scoren!’ Wat doet een ervaren biljarter dan? Hij zou toch geen knip voor z’n neus waard zijn als hij de handdoek in de ring wierp? Hij staat op, loopt langzaam naar de tafel, hij krijt, bekijkt het spel op het laken vanuit elke hoek. Het publiek stroomt toe. De biljarter kan niet meer terug. Op woensdag mei ’s nachts om half twee sneuvelde het correctief referendum kort voor de eindstreep, na een debat van zestien uur. Het voorstel om dit nieuwe staatkundige instrument in de Grondwet op te nemen, kreeg in tweede lezing uiteindelijk steun van van de leden van de Eerste Kamer, één te weinig om de horde van tweederde te nemen. Die nacht voltrok zich een spectaculair schouwspel met een spanningsboog die intact bleef tot aan de verrassende ontknoping: het ‘tegen’ van -coryfee Hans Wiegel. De Nederlandse tv-kijker bleef massaal op. Een speciale uitzending op Nederland van middernacht tot twee uur trok . toeschouwers en werd bovengemiddeld gewaardeerd met . als topamu- sement. De volgende dag kwamen alle ministers in spoedberaad bijeen. Een paar uur later bood minister-president Kok de koningin het ontslag van zijn kabinet aan. De nacht van Wiegel ligt nog te dichtbij om hem parlementair historisch goed te duiden. Blijft het bij een rimpeling, een kamikazeactie van een afgedankt leider? Is het gekramde kabinet wankel geworden of staat het steviger? De nieuwe politieke leiders – Melkert, Dijk- stal, De Graaf – werden op de proef gesteld. -

Tales of Members of the Resistance and Victims of War

Come tell me after all these years your tales about the end of war Tales of members of the resistance and victims of war Ellen Lock Come tell me after all these years your tales about the end of war tell me a thousand times or more and every time I’ll be in tears. by Leo Vroman: Peace Design: Irene de Bruijn, Ellen Lock Cover picture: Leo en Tineke Vroman, photographer: Keke Keukelaar Interviews and pictures: Ellen Lock, unless otherwise stated Translation Dutch-English: Translation Agency SVB: Claire Jordan, Janet Potterton. No part of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the editors of Aanspraak e-mail: [email protected], website: www.svb.nl/wvo © Sociale Verzekeringsbank / Pensioen- en Uitkeringsraad, december 2014. ISBN 978-90-9030295-9 Tales of members of the resistance and victims of war Sociale Verzekeringsbank & Pensioen- en Uitkeringsraad Leiden 2014 Content Tales of Members of the Resistance and Victims of War 10 Martin van Rijn, State Secretary for Health, Welfare and Sport 70 Years after the Second World War 12 Nicoly Vermeulen, Chair of the Board of Directors of the Sociale Verzekeringsbank (SVB) Speaking for your benefit 14 Hans Dresden, Chair of the Pension and Benefit Board Tales of Europe Real freedom only exists if everyone can be free 17 Working with the resistance in Amsterdam, nursery teacher Sieny Kattenburg saved many Jewish children from deportation from the Hollandsche Schouwburg theatre. Surviving in order to bear witness 25 Psychiatrist Max Hamburger survived the camps at Auschwitz and Buchenwald. We want the world to know what happened 33 in the death camp at Sobibor! Sobibor survivor Jules Schelvis tells his story. -

Personalization of Political Newspaper Coverage: a Longitudinal Study in the Dutch Context Since 1950

Personalization of political newspaper coverage: a longitudinal study in the Dutch context since 1950 Ellis Aizenberg, Wouter van Atteveldt, Chantal van Son, Franz-Xaver Geiger VU University, Amsterdam This study analyses whether personalization in Dutch political newspaper coverage has increased since 1950. In spite of the assumption that personalization increased over time in The Netherlands, earlier studies on this phenomenon in the Dutch context led to a scattered image. Through automatic and manual content analyses and regression analyses this study shows that personalization did increase in The Netherlands during the last century, the changes toward that increase however, occurred earlier on than expected at first. This study also shows that the focus of reporting on politics is increasingly put on the politician as an individual, the coverage in which these politicians are mentioned however became more substantive and politically relevant. Keywords: Personalization, content analysis, political news coverage, individualization, privatization Introduction When personalization occurs a focus is put on politicians and party leaders as individuals. The context of the news coverage in which they are mentioned becomes more private as their love lives, upbringing, hobbies and characteristics of personal nature seem increasingly thoroughly discussed. An article published in 1984 in the Dutch newspaper De Telegraaf forms a good example here, where a horse race betting event, which is attended by several ministers accompanied by their wives and girlfriends is carefully discussed1. Nowadays personalization is a much-discussed phenomenon in the field of political communication. It can simply be seen as: ‘a process in which the political weight of the individual actor in the political process increases 1 Ererondje (17 juli 1984). -

Den Uyl, Lay-Out

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Joop den Uyl 1919-1987 : dromer en doordouwer Bleich, A. Publication date 2008 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bleich, A. (2008). Joop den Uyl 1919-1987 : dromer en doordouwer. Uitgeverij Balans. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:02 Oct 2021 Den Uyl-revisie 18-01-2008 10:08 Pagina 373 Hoofdstuk 15 Geen tweede kabinet-Den Uyl Was de val van het kabinet-Den Uyl slechts een incident? Of was het een teken dat in de moeizame relatie tussen socialisten en christen-demo- craten iets kapot was gegaan? Tijd om uitvoerig stil te staan bij de oor- zaken van de botsingen die steeds frequenter en heftiger in en rond het kabinet hadden plaatsgevonden, was er niet.