Discoveries Made While Preserving the Star-Spangled Banner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fort Mchenry - "Our Country" Bicentennial Festivities, Baltimore, MD, 7/4/75 (2)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 67, folder “Fort McHenry - "Our Country" Bicentennial Festivities, Baltimore, MD, 7/4/75 (2)” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON '!0: Jack Marsh FROM: PAUL THEIS a>f Although belatedly, attached is some material on Ft. McHenry which our research office just sent in ••• and which may be helpful re the July 4th speech. Digitized from Box 67 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library :\iE\10 R.-\~ D l. \I THE \\'HITE HOI.SE \L\Sllli"GTO:'\ June 23, 1975 TO: PAUL 'IHEIS FROM: LYNDA DURFEE RE: FT. McHENRY FOURTH OF JULY CEREMONY Attached is my pre-advance report for the day's activities. f l I I / I FORT 1:vlc HENRY - July 4, 1975 Progran1 The program of events at Fort McHenry consists of two parts, with the President participating in the second: 11 Part I: "By the Dawn's Early Light • This is put on by the Baltimore Bicentennial Committee, under the direction of Walter S. -

A History of the War of 1812 and the Star-Spangled Banner

t t c c A History of the War of 1812 and The Star-Spangled e e j j Banner o o r r Objectives: Students will be able to cite the origins and outcome of the War of 1812 P P and be able to place the creation of the Star-Spangled Banner in a chronological framework. r r e e Time: 3 to 5 class periods, depending on extension activities n n Skills: Reading, chronological thinking, map-making. n Content Areas: Language Arts- Vocabulary, Language Arts- Reading, Social Studies- n a a Geography, Social Studies- United States history Materials: B B ♦ Poster board or oak tag d d ♦ Colored markers e e l l ♦ Pencils g g ♦ Copies of reading material n n a a Standards: p p NCHS History Standards S S K-4 Historical Thinking Standards - - 1A: Identify the temporal structure of a historical narrative or story. r r 1F: Create timelines. a a t t 5A: Identify problems and dilemmas confronting people in historical S S stories, myths, legends, and fables, and in the history of their school, community, state, nation, and the world. e e 5B: Analyze the interests, values, and points of view of those h h involved in the dilemma or problem situation. T T K-4 Historical Content Standards 4D: The student understands events that celebrate and exemplify fundamental values and principles of American democracy. 4E: The student understands national symbols through which American values and principles are expressed. 5-12 Historical Thinking Standards 1A: Identify the temporal structure of a historical narrative or story. -

Letter from Eben Appleton to Charles Walcott, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1912. New York December 12Th, 1912

Letter from Eben Appleton to Charles Walcott, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, 1912. New York December 12th, 1912 Mr. Charles Walcott, Secty Smithsonian Institute Washington, D.C. Dear Sir: If agreeable to you and the authorities in charge of the National Museum, I shall be very glad to present to that Institution that flag owned by me, and now in possession of the Museum as a loan from me, and known as the Star-Spangled Banner. It has always been my intention to present the flag during my life time to that Institution in the country where it could be conveniently seen by the public, and where it would be well cared for, and the advantages and the appropriateness of the National Museum are so obvious, as to render consideration of any other place unnecessary. Whilst realizing that the poem of Mr. Key is the one thing which renders this flag of more than ordinary interest, it is only right to appreciate the fact that there was a cause for his inspiration. Being detained temporarily on board a British Man of War, he witnessed the bombardment of Fort McHenry, and was inspired by that dramatic scene to give to the Nation his beautiful lines. I must ask therefore, as a condition of this gift, and injustice to the Commandant of the Fort, and the brave men under him, that their share in the inspiration of this poem be embodied in the inscription to be placed in the case containing this flag. I have had forwarded to me copies of the inscriptions contained in the case at present, and do not think they could be improved upon, but as I desire now to make a specific choice, will say that the following is the one which I prefer, and should like to be assured by you will be the official marking-- The Star Spangled Banner Garrison Flag of Fort McHenry, Baltimore, during the bombardment of the Fort by the British Sept.13-14, 1814, when it was gallantly and successfully [sic.] defended by colonel George Armistead, and the brave men under him. -

Volume 5 Fort Mchenry.Pdf

American Battlefield Trust Volume 5 BROADSIDE A Journal of the Wars for Independence for Students Fort McHenry and the Birth of an Anthem Of all the battles in American history none is more With a war being fought on the periphery of the Unit- connected with popular culture than the battle of Fort ed States the British, under the influence of Admiral McHenry fought during the War of 1812. The British George Cockburn, decided to bring the war more di- attack on Fort McHenry and the rectly to America by attacking the large garrison flag that could be Chesapeake Region. The British seen through the early morning Navy, with Marines and elements mist, inspired Washington, DC of their army wreaked havoc along lawyer Francis Scott Key to pen the Chesapeake burning numer- what in 1931 would be adopted ous town and settlements. Howev- by Congress as our National An- er, Cockburn had two prizes in them, the Star-Spangled Ban- mind – Washington, DC and Bal- ner. The anthem is played be- timore, Maryland. Retribution for fore countless sports events the burning of York was never far from high school through the from his mind and what a blow he ranks of professional games. thought, would it be to American The story of the creation of the morale if he could torch the still Star-Spangled Banner is as developing American capital. Af- compelling as the story of the ter pushing aside a motley assort- attack on Baltimore. ment of American defenders of the approach to Washington, DC In 1812, a reluctant President at the battle of Bladensburg, Mar- James Madison asked Congress yland, Cockburn and his forces for a Declaration of War against entered the city and put the torch Great Britain. -

![The Star-Spangled Banner Project: Save Our History[TM]. Teacher's Manual, Grades K-8](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6224/the-star-spangled-banner-project-save-our-history-tm-teachers-manual-grades-k-8-486224.webp)

The Star-Spangled Banner Project: Save Our History[TM]. Teacher's Manual, Grades K-8

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 450 018 SO 032 384 AUTHOR O'Connell, Libby, Ed. TITLE The Star-Spangled Banner Project: Save Our History[TM]. Teacher's Manual, Grades K-8. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 62p.; This teacher's manual was produced in cooperationwith the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History. AVAILABLE FROM A&E Television Networks, Attn: CommunityMarketing, 235 East 45th Street, New York, NY 10017; Tel: 877-87LEARN (toll free); Fax: 212-551-1540; E-mail: ([email protected]); Web site: http://www.historychannel.com/classroom/index.html. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC03 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Curriculum Enrichment; Elementary Education; *Heritage Education; *Interdisciplinary Approach; Middle Schools; Social Studies; Teaching Guides; *United States History IDENTIFIERS National History Standards; Smithsonian Institution; *Star Spangled Banner; War of 1812 ABSTRACT The Star-Spangled Banner is the original flag that flew over Fort McHenry in Baltimore (Maryland) during its attackby the British during the War of 1812. It inspired Francis Scott Key, a lawyerbeing held on board a British ship in Baltimore Harbor, towrite a poem that later became the words to the national anthem. Since 1907, the Star-Spangled Bannerhas been part of the collection at the Smithsonian Institutionand has hung as the centerpiece of the National Museum of American History inWashington for over 30 years. Now the flag is being examined, cleaned,repaired, and preserved for future generations. This teacher's manual about the flag'shistory features an interdisciplinary project that focuses on history,music, language arts, and science. Following an introduction, themanual is divided into grade-level sections: Section One: Grades K-2; Section Two:Grades 3-5; and Section Three: Grades 6-8. -

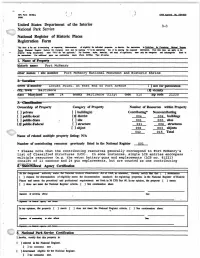

Mdl Ilem "7 .Nd

.. ) ''· I United States Department of the Interior B-8 National Park Service Nadonal Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1\il ..... ii .. - ill ~-. .......w.a ........... ol clip.llily far llldMUI ....- • diArico. Soc ils1rcdaal • Quidtliia .. Conpetinr Noliaml l!gi!w fl!:!!!! (NKloml llllPeer lllllal• 16). ~ mdl ilem "7 .nD,. •a• ill• ....,..... "'- er bJ _.. .. .....-i WarDllca. ltu ilom ** • llppl7 • dlt ,....,,, 111i1s ....,_..... - "NIA" far ... awlicoblc." Far f\aUca, ICylca, _..., ud - ol 1ipi"'-e, - cllllJ die c:MepW ud ........... liled im llliJ ........... Far ..idibanll ... - CGllinatlclli ..... (J'Gr9 IG«Xla). ,.,,. Ill --.. l. Name ol Property historic name Fort McHenry other names I sate number Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine Street & number Locust Point, at east end of Port Avenue l ] not tor pubiicabon Cify, town Bal hmore Lil VIClDltY state Matyaana coae 2 4 county Baltimore (City) coae 510 bp cooe 21230 Ownership or Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property [ ) private [ 1 build.ing(s) Contributing• Noncontributing [ ) public-local [ J) district 004 006 buildings [ 1 public-State [ 1 site 001 ooo sites [ J) public-Federal [ 1 structure 031 006 structures [ J object 006 003 objects 042 015 Total Name of related multiple property listing: N/A Number or contributing resources previomly listed In the National Register 001 * Please note that the contributing resources generally correspond to Fort McHenry' s List of Classified Structures (LCS ) . In some instances, single LCS entries encompass multiple resources (e.g . the water battery guns and emplacements (LCS no. 81221) consist of 11 cannons and 24 gun emplacements, but are counted as one contributing .f.t~~ Agmcy Catilicatioa ere y ce DO of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering propenies in cbe National Register of Hisloric Places and meeu d:le procedural and professional requirements let forth in 36 CPR Put 60. -

“Second War of Independence,” Lit the Baltimore Skies in 1814

Baltimore in the War of 1812 The War of 1812, often called America’s “Second War of Independence,” lit the Baltimore skies in 1814. Expecting to cruise with little resistance into the city’s harbor, a British fleet was instead frustrated by American forces at North Point and inside Fort McHenry. The courage of the fort’s defenders during the Battle of Baltimore was witnessed by Francis Scott Key, a Maryland lawyer detained on board a truce vessel after facilitating an American prisoner’s release. Key watched bombs burst along the shoreline and rockets zooming across the sky. But when the smoke cleared and British ships pulled back, a large American flag—measuring 42 feet by 30 feet—fluttered over the fort’s ramparts, prompting him to write the poem that became the national anthem. Day One: Begin your day at the Baltimore Visitor Center at the Inner Harbor. Here, a new exhibit will introduce you to the Bicentennial of the War of 1812 and “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Learn about special events, purchase tickets for attractions, tours and harbor cruises, pick up brochures, and make reservations for dining and lodging—all in one convenient location. Next, make your way to Baltimore’s Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, site of the battle that inspired Francis Scott Key to pen the poem that would later become “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Fort McHenry features exhibits, tours, and lush grounds. Visit the new Fort McHenry Visitor and Education Center to see a dramatic film about the War of 1812. Learn about the Battle of Baltimore and walk the ramparts of the star-shaped fort. -

The Society Participates in a Ceremony Honoring Lt Col George Armistead November 2, 2014

The Society Participates in a Ceremony Honoring Lt Col George Armistead November 2, 2014 Past President, Mike Lyman of the Society of the War of 1812 in the Commonwealth of Virginia and Councilor Charles Belfield of the Society traveled to the Newmarket Plantation in Caroline County to participate in the unveiling of a new historical roadside marker honoring Lt Col George Armistead who was born on the plantation. The marker was installed on U.S. Route 301 at the entrance to the plantation, however because of limited parking, the ceremony was conducted at the nearby Plantation Cemetery where a monument has his name inscribed. Lyman and Belfield provided the Star Spangled Banner flag which they posted near the monument. Belfield presented the Society wreath and Lyman the Virginia War of 1812 Bicentennial Commission wreath. Lyman also gave greetings from the Society and the Commission The event was conducted by the Caroline County Historical Society. Although the weather was very cold and windy the ceremony was attended by approximately fifty people. The cemetery was surrounded by huge oak trees that were planted in the mid eighteenth century Department of Historic Resources (www.dhr.virginia.gov) For Immediate Release October 23, 2014 STATE HISTORICAL HIGHWAY MARKER “LT. COL. GEORGE ARMISTEAD (1780-1818)” TO BE DEDICATED —Marker recalls Caroline County native who was commanding officer at Fort McHenry during the Battle of Baltimore in 1814, which inspired “The Star Spangled Banner”— —The marker’s text is reproduced below— RICHMOND – A state historical marker issued by the Virginia Department of Historic Resources that honors Lt. -

The Star Spangled Banner: a Dramatic Retelling of the Story of Our National Anthem the Star Spangled Banner: the Story & the Song

The Star Spangled Banner: A Dramatic Retelling of the Story of Our National Anthem The Star Spangled Banner: The Story & the Song Overview Cast . Stagehands 1 and 2 . Narrators 1, 2, 3, 4 . George III, King of Great Britain and Ireland . James Madison, fourth President of the United States . Dolley Madison, First Lady . American soldiers . British sailors . Citizens of Baltimore . Major George Armistead, commander at Fort McHenry . American Officers 1 and 2 . Mary Pickersgill, flag maker . Carolyn Pickersgill, Mary’s daughter . Rebecca Young, Mary’s mother . Eliza Young, Mary’s niece . Margaret Young, Mary’s niece . Francis Scott Key, young lawyer from Washington, D.C. Colonel John S. Skinner, U.S. Commissioner General of Prisoners . Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander F.I. Cochrane, commander-in-chief of 50 warships during the Chesapeake Campaign in 1814 . Dr. William Beanes, U.S. prisoner arrested for allegedly violating a pledge of good conduct after the Battle of Bladensburg, outside Washington, D.C. Page 1 of 13 Distributed through the Barat Teaching with Primary Sources Program | 847-574-2465 Find additional training & materials at http://primarysourcenexus.org. Costumes Students can wear pictures of the main characters (see Character Illustration References section) and/or large nametags that have been laminated with tie yarn strings to wear around their necks; sailors and soldiers can make hats out of newspaper Props . cards with scene titles . picture of Napoleon Bonaparte1 mounted on cardstock . pictures of the American frigate Enterprise2 and the British war ship Boxer3 mounted on cardstock . picture of W. Charles’ Boxing Match4 mounted on cardstock . picture of Fort McHenry5 mounted on cardstock . -

Teacher's Resource Guide

EXHIBIT INTRODUCTION During a visit to Becoming Michigan: From Revolution to Statehood, at the Lorenzo Cultural Center students will discover both the universal and the unique about one of the most defining decades in our nation’s early history. This packet of information is designed to assist teachers in making the most of their students’ visit to the Lorenzo Cultural Center. Contained in this packet are: 1. An outline of the exhibit 2. Facts, information, and activities related to Becoming Michigan 3. Lesson plans related to Becoming Michigan 4. A resource list with websites, addresses and information 2 Reprinted with permission Becoming Michigan: From Revolution to Statehood Lorenzo Cultural Center, February 25-May 5, 2012 EXHIBIT FLOOR PLAN 3 Reprinted with permission Becoming Michigan: From Revolution to Statehood Lorenzo Cultural Center, February 25-May 5, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction………………………………………………………………………………....2 Part I: Exhibit Outline……………………………………………………………….…....5 Part II: Becoming Michigan Fact and Information Timeline……………………………...6 Part III: Background Information………………………………………………………......9 Part IV: Lesson Plans for the Classroom: Anishinabe-Ojibwe-Chippewa: Culture of an Indian Nation……………..…….. 30 Test of Courage “Old Ironsides” is Born…….…………………………………..36 Teaching with Documents; Launching the New U.S. Navy.…………………….39 President Madison’s 1812 War Message………………………………………...43 Oh, Say, Can You See what the Star Spangled Banner Means?….…...…………46 The Star Spangled Banner, Words by Francis Scott Key…..……………………49 Packing the Wagon..……………………………………….…………………….51 Part V: Other Resources…………………………………………………………………..54 Part VI: Presentations……………………………………………. ……………………....55 4 Reprinted with permission Becoming Michigan: From Revolution to Statehood Lorenzo Cultural Center, February 25-May 5, 2012 PART I: EXHIBIT OUTLINE Introduction Join us at the Lorenzo Cultural Center as we bring the state's early history to life through a wide range of exhibits, presentations, and activities. -

What Does the Star-Spangled Banner Mean to You?

HISTORICALLY SPEAKING Guess Correct 1. Our National Anthem, The Star Spangled Banner, was written during which war? A. the American Revolution B. the War of 1812 C. the Civil War 2. Who was the lawyer who wrote the lyrics to The Star Spangled Banner while watching a battle from a ship? A. Francis Scott Key B. Major George Armistead C. Dr. William Beanes 3. What fort that was built in the shape of a five-pointed star protected the city of Baltimore, Maryland? A. Fort McHenry B. Fort Washington C. Fort Flag 4. What is a rampart? A. a canon B. a low dirt wall surrounding a fort C. a lookout tower 5. What did Major George Armistead from Fort McHenry ask Mary Pickersgill to make so that even the British could see it from a great distance? A. a very large ship B. a very large rampart C. a very large flag 6. How many stars and stripes did the original Fort McHenry flag have? A. 15 stars and 15 stripes B. 13 stars and 13 stripes C. 50 stars and 13 stripes 7. What time of day did the battle begin? A. Dawn B. Midnight C. Twilight 8. With its first title being “The Defense of Fort McHenry”, the poem for the Star-Spangled Banner originally had how many verses? A. one B. three C. four 9. What tune was Francis Scott Key thinking of when he wrote his poem on the back of an old envelope? A. “To Anachreon in Heaven” B. “Yankee Doodle” C. “Our National Anthem” 10. -

FORT Mchenry National Monument and Historic Shrine Maryland

FORT McHENRY UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Stewart L. Udall, Secretary NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Conrad L. Wirth, Director HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER FIVE This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System. It is printed by the Government Printing Office, and may be pur chased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington 25, D. C. Price 25 cents FORT McHENRY National Monument and Historic Shrine Maryland h Harold I. Lessem and George C. Mackenzie NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES No. 5 Washington, D.C, 1954 Reprint 1961 The National Park System, of which Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and enjoyment of its people. Qontents Page FORT WHETSTONE, 1776-97; FORT McHENRY, 1798-1812 1 THE WAR OF 1812 4 THE CHESAPEAKE CAMPAIGN 5 BALTIMORE, THE BRITISH OBJECTIVE 6 THE BATTLE OF NORTH POINT 9 THE BOMBARDMENT OF FORT McHENRY ... 10 MAJ. GEORGE ARMISTEAD, COMMANDER OF FORT McHENRY 13 "THE STAR-SPANGLED BANNER" 15 FRANCIS SCOTT KEY 23 "THE STAR-SPANGLED BANNER" AFTER 1815 . 24 BRITISH BOMBS 27 BRITISH ROCKETS 29 FORT McHENRY AFTER 1814 31 FORT McHENRY TODAY "34 MUSEUMS 37 HOW TO REACH THE FORT 38 SERVICES TO THE PUBLIC 38 RELATED AREAS 38 ADMINISTRATION 38 The interior of Fort McHenry as seen through the sally port. ORT McHENRY occupies a preeminent position among the historic shrines and monuments of our country by reason of its special meaning in F American history.