030626 Mitochondrial Respiratory-Chain Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B Activin a Receptor, Type IB

Table S1. Kinase clones included in human kinase cDNA library for yeast two-hybrid screening Gene Symbol Gene Description ACVR1B activin A receptor, type IB ADCK2 aarF domain containing kinase 2 ADCK4 aarF domain containing kinase 4 AGK multiple substrate lipid kinase;MULK AK1 adenylate kinase 1 AK3 adenylate kinase 3 like 1 AK3L1 adenylate kinase 3 ALDH18A1 aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family, member A1;ALDH18A1 ALK anaplastic lymphoma kinase (Ki-1) ALPK1 alpha-kinase 1 ALPK2 alpha-kinase 2 AMHR2 anti-Mullerian hormone receptor, type II ARAF v-raf murine sarcoma 3611 viral oncogene homolog 1 ARSG arylsulfatase G;ARSG AURKB aurora kinase B AURKC aurora kinase C BCKDK branched chain alpha-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase BMPR1A bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type IA BMPR2 bone morphogenetic protein receptor, type II (serine/threonine kinase) BRAF v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 BRD3 bromodomain containing 3 BRD4 bromodomain containing 4 BTK Bruton agammaglobulinemia tyrosine kinase BUB1 BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog (yeast) BUB1B BUB1 budding uninhibited by benzimidazoles 1 homolog beta (yeast) C9orf98 chromosome 9 open reading frame 98;C9orf98 CABC1 chaperone, ABC1 activity of bc1 complex like (S. pombe) CALM1 calmodulin 1 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM2 calmodulin 2 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CALM3 calmodulin 3 (phosphorylase kinase, delta) CAMK1 calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase I CAMK2A calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II alpha CAMK2B calcium/calmodulin-dependent -

Supplement 1 Overview of Dystonia Genes

Supplement 1 Overview of genes that may cause dystonia in children and adolescents Gene (OMIM) Disease name/phenotype Mode of inheritance 1: (Formerly called) Primary dystonias (DYTs): TOR1A (605204) DYT1: Early-onset generalized AD primary torsion dystonia (PTD) TUBB4A (602662) DYT4: Whispering dystonia AD GCH1 (600225) DYT5: GTP-cyclohydrolase 1 AD deficiency THAP1 (609520) DYT6: Adolescent onset torsion AD dystonia, mixed type PNKD/MR1 (609023) DYT8: Paroxysmal non- AD kinesigenic dyskinesia SLC2A1 (138140) DYT9/18: Paroxysmal choreoathetosis with episodic AD ataxia and spasticity/GLUT1 deficiency syndrome-1 PRRT2 (614386) DYT10: Paroxysmal kinesigenic AD dyskinesia SGCE (604149) DYT11: Myoclonus-dystonia AD ATP1A3 (182350) DYT12: Rapid-onset dystonia AD parkinsonism PRKRA (603424) DYT16: Young-onset dystonia AR parkinsonism ANO3 (610110) DYT24: Primary focal dystonia AD GNAL (139312) DYT25: Primary torsion dystonia AD 2: Inborn errors of metabolism: GCDH (608801) Glutaric aciduria type 1 AR PCCA (232000) Propionic aciduria AR PCCB (232050) Propionic aciduria AR MUT (609058) Methylmalonic aciduria AR MMAA (607481) Cobalamin A deficiency AR MMAB (607568) Cobalamin B deficiency AR MMACHC (609831) Cobalamin C deficiency AR C2orf25 (611935) Cobalamin D deficiency AR MTRR (602568) Cobalamin E deficiency AR LMBRD1 (612625) Cobalamin F deficiency AR MTR (156570) Cobalamin G deficiency AR CBS (613381) Homocysteinuria AR PCBD (126090) Hyperphelaninemia variant D AR TH (191290) Tyrosine hydroxylase deficiency AR SPR (182125) Sepiaterine reductase -

Initial Experience in the Treatment of Inherited Mitochondrial Disease with EPI-743

Molecular Genetics and Metabolism 105 (2012) 91–102 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Molecular Genetics and Metabolism journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ymgme Initial experience in the treatment of inherited mitochondrial disease with EPI-743 Gregory M. Enns a,⁎, Stephen L. Kinsman b, Susan L. Perlman c, Kenneth M. Spicer d, Jose E. Abdenur e, Bruce H. Cohen f, Akiko Amagata g, Adam Barnes g, Viktoria Kheifets g, William D. Shrader g, Martin Thoolen g, Francis Blankenberg h, Guy Miller g,i a Department of Pediatrics, Division of Medical Genetics, Lucile Packard Children's Hospital, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305-5208, USA b Division of Neurosciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC 29425, USA c Department of Neurology, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA d Department of Radiology and Radiological Science, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC 29425, USA e Department of Pediatrics, Division of Metabolic Disorders, CHOC Children's Hospital, Orange County, CA 92868, USA f Department of Neurology, NeuroDevelopmental Science Center, Akron Children's Hospital, Akron, OH 44308, USA g Edison Pharmaceuticals, 350 North Bernardo Avenue, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA h Department of Radiology, Division of Pediatric Radiology, Lucile Packard Children's Hospital, Stanford, CA 94305, USA i Department of Anesthesiology, Critical Care Medicine, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305, USA article info abstract Article history: Inherited mitochondrial respiratory chain disorders are progressive, life-threatening conditions for which Received 22 September 2011 there are limited supportive treatment options and no approved drugs. Because of this unmet medical Received in revised form 17 October 2011 need, as well as the implication of mitochondrial dysfunction as a contributor to more common age- Accepted 17 October 2011 related and neurodegenerative disorders, mitochondrial diseases represent an important therapeutic target. -

Identification of the Drosophila Melanogaster Homolog of the Human Spastin Gene

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Dev Genes Evol (2003) 213:412–415 DOI 10.1007/s00427-003-0340-x EXPRESSION NOTE Lars Kammermeier · Jrg Spring · Michael Stierwald · Jean-Marc Burgunder · Heinrich Reichert Identification of the Drosophila melanogaster homolog of the human spastin gene Received: 14 April 2003 / Accepted: 5 May 2003 / Published online: 5 June 2003 Springer-Verlag 2003 Abstract The human SPG4 locus encodes the spastin gene encoding spastin. This gene is expressed ubiqui- gene, which is responsible for the most prevalent form tously in fetal and adult human tissues (Hazan et al. of autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia 1999). The highest expression levels are found in the (AD-HSP), a neurodegenerative disorder. Here we iden- brain, with selective expression in the cortex and striatum. tify the predicted gene product CG5977 as the Drosophila In the spinal cord, spastin is expressed exclusively in homolog of the human spastin gene, with much higher nuclei of motor neurons, suggesting that the strong sequence similarities than any other related AAA domain neurodegenerative defects observed in patients are caused protein in the fly. Furthermore we report a new potential by a primary defect of spastin in neurons (Charvin et al. transmembrane domain in the N-terminus of the two 2003). The human spastin gene encodes a predicted 616- homologous proteins. During embryogenesis, the expres- amino-acid long protein and is a member of the large sion pattern of Drosophila spastin becomes restricted family of proteins with an AAA domain (ATPases primarily to the central nervous system, in contrast to the Associated with diverse cellular Activities). -

Dual Role of the Mitochondrial Protein Frataxin in Astrocytic Tumors

Laboratory Investigation (2011) 91, 1766–1776 & 2011 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0023-6837/11 $32.00 Dual role of the mitochondrial protein frataxin in astrocytic tumors Elmar Kirches1, Nadine Andrae1, Aline Hoefer2, Barbara Kehler1,3, Kim Zarse4, Martin Leverkus3, Gerburg Keilhoff5, Peter Schonfeld5, Thomas Schneider6, Annette Wilisch-Neumann1 and Christian Mawrin1 The mitochondrial protein frataxin (FXN) is known to be involved in mitochondrial iron homeostasis and iron–sulfur cluster biogenesis. It is discussed to modulate function of the electron transport chain and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). FXN loss in neurons and heart muscle cells causes an autosomal-dominant mitochondrial disorder, Friedreich’s ataxia. Recently, tumor induction after targeted FXN deletion in liver and reversal of the tumorigenic phenotype of colonic carcinoma cells following FXN overexpression were described in the literature, suggesting a tumor suppressor function. We hypothesized that a partial reversal of the malignant phenotype of glioma cells should occur after FXN transfection, if the mitochondrial protein has tumor suppressor functions in these brain tumors. In astrocytic brain tumors and tumor cell lines, we observed reduced FXN levels compared with non-neoplastic astrocytes. Mitochondrial content (citrate synthase activity) was not significantly altered in U87MG glioblastoma cells stably overexpressing FXN (U87-FXN). Surprisingly, U87-FXN cells exhibited increased cytoplasmic ROS levels, although mitochondrial ROS release was attenuated by FXN, as expected. Higher cytoplasmic ROS levels corresponded to reduced activities of glutathione peroxidase and catalase, and lower glutathione content. The defect of antioxidative capacity resulted in increased susceptibility of U87-FXN cells against oxidative stress induced by H2O2 or buthionine sulfoximine. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Pathogenic Variants in the AFG3L2 Proteolytic Domain Cause SCA28

Neurogenetics J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmedgenet-2018-105766 on 25 March 2019. Downloaded from ORIGINAL ARTICLE Pathogenic variants in the AFG3L2 proteolytic domain cause SCA28 through haploinsufficiency and proteostatic stress-driven OMA1 activation Susanna, Tulli 1 Andrea Del Bondio,1 Valentina Baderna,1 Davide Mazza,2 Franca Codazzi,3,4 Tyler Mark Pierson,5 Alessandro Ambrosi,3 Dagmar Nolte,6 Cyril Goizet,7,8 ,Camilo Toro 9 Jonathan Baets,10,11 Tine Deconinck,10,11 Peter DeJonghe,10,11 Paola Mandich,12 Giorgio Casari,3,13 Francesca Maltecca 1,3 ► Additional material is ABSTRact wustl. edu/ ataxia/domatax. html), SCA type 28 published online only. To view Background Spinocerebellar ataxia type 28 (SCA28) (SCA28; MIM #610246) is the only one caused please visit the journal online is a dominantly inherited neurodegenerative disease by pathogenic variants in a resident mitochondrial (http:// dx. doi. org/ 10. 1136/ 1 jmedgenet- 2018- 105766). caused by pathogenic variants in AFG3L2. The AFG3L2 protein, AFG3L2. The clinical spectrum of SCA28 protein is a subunit of mitochondrial m-AAA complexes comprises slowly progressive gait and limb ataxia, For numbered affiliations see involved in protein quality control. Objective of this study and oculomotor abnormalities (eg, ophthalmopa- end of article. was to determine the molecular mechanisms of SCA28, resis and ptosis) as typical signs.2 which has eluded characterisation to date. AFG3L2 belongs to the AAA-protease subfamily Correspondence to Dr Francesca Maltecca, Division Methods -

My Beloved Neutrophil Dr Boxer 2014 Neutropenia Family Conference

The Beloved Neutrophil: Its Function in Health and Disease Stem Cell Multipotent Progenitor Myeloid Lymphoid CMP IL-3, SCF, GM-CSF CLP Committed Progenitor MEP GMP GM-CSF, IL-3, SCF EPO TPO G-CSF M-CSF IL-5 IL-3 SCF RBC Platelet Neutrophil Monocyte/ Basophil B-cells Macrophage Eosinophil T-Cells Mast cell NK cells Mature Cell Dendritic cells PRODUCTION AND KINETICS OF NEUTROPHILS CELLS % CELLS TIME Bone Marrow: Myeloblast 1 7 - 9 Mitotic Promyelocyte 4 Days Myelocyte 16 Maturation/ Metamyelocyte 22 3 – 7 Storage Band 30 Days Seg 21 Vascular: Peripheral Blood Seg 2 6 – 12 hours 3 Marginating Pool Apoptosis and ? Tissue clearance by 0 – 3 macrophages days PHAGOCYTOSIS 1. Mobilization 2. Chemotaxis 3. Recognition (Opsonization) 4. Ingestion 5. Degranulation 6. Peroxidation 7. Killing and Digestion 8. Net formation Adhesion: β 2 Integrins ▪ Heterodimer of a and b chain ▪ Tight adhesion, migration, ingestion, co- stimulation of other PMN responses LFA-1 Mac-1 (CR3) p150,95 a2b2 a CD11a CD11b CD11c CD11d b CD18 CD18 CD18 CD18 Cells All PMN, Dendritic Mac, mono, leukocytes mono/mac, PMN, T cell LGL Ligands ICAMs ICAM-1 C3bi, ICAM-3, C3bi other other Fibrinogen other GRANULOCYTE CHEMOATTRACTANTS Chemoattractants Source Activators Lipids PAF Neutrophils C5a, LPS, FMLP Endothelium LTB4 Neutrophils FMLP, C5a, LPS Chemokines (a) IL-8 Monocytes, endothelium LPS, IL-1, TNF, IL-3 other cells Gro a, b, g Monocytes, endothelium IL-1, TNF other cells NAP-2 Activated platelets Platelet activation Others FMLP Bacteria C5a Activation of complement Other Important Receptors on PMNs ñ Pattern recognition receptors – Detect microbes - Toll receptor family - Mannose receptor - bGlucan receptor – fungal cell walls ñ Cytokine receptors – enhance PMN function - G-CSF, GM-CSF - TNF Receptor ñ Opsonin receptors – trigger phagocytosis - FcgRI, II, III - Complement receptors – ñ Mac1/CR3 (CD11b/CD18) – C3bi ñ CR-1 – C3b, C4b, C3bi, C1q, Mannose binding protein From JG Hirsch, J Exp Med 116:827, 1962, with permission. -

Assembling the Mitochondrial ATP Synthase Jiyao Songa, Nikolaus Pfannera,B,1, and Thomas Beckera,B

COMMENTARY COMMENTARY Assembling the mitochondrial ATP synthase Jiyao Songa, Nikolaus Pfannera,b,1, and Thomas Beckera,b Mitochondria are known as the powerhouses of the of the ATP synthase (5–7). A recent high-resolution cell. The F1Fo-ATP synthase of the mitochondrial inner cryoelectron microscopic structure of the dimeric Fo membrane produces the bulk of cellular ATP. The re- region of yeast ATP synthase revealed that the subunits spiratory chain complexes pump protons across the Atp6 and i/j form the contact sites between two ATP inner membrane into the intermembrane space and synthase monomers, supported by interaction between thereby generate a proton-motive force that drives subunits e and k (8). In mitochondria, rows of ATP syn- the ATP synthase. In a fascinating molecular mecha- thase dimers localize to the rims of the cristae mem- nism, the ATP synthase couples the synthesis of ATP branes, which are invaginations of the inner membrane. to the transport of protons into the matrix (1–3). For- The ATP synthase dimers bend the inner membrane mation of the ATP synthase depends on the associa- and are crucial for forming the typical cristae shape (9, tion of 17 different structural subunits of dual genetic 10). The supernumerary subunits e and g, together with origin. Whereas a number of assembly factors and the N-terminal portion of the peripheral stalk subunit b, steps have been identified in the model organism affect the curvature of the inner membrane (8, 9, 11). baker’s yeast, little has been known about the assem- Thus, the ATP synthase not only synthesizes ATP but bly of the human ATP synthase. -

Low Abundance of the Matrix Arm of Complex I in Mitochondria Predicts Longevity in Mice

ARTICLE Received 24 Jan 2014 | Accepted 9 Apr 2014 | Published 12 May 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms4837 OPEN Low abundance of the matrix arm of complex I in mitochondria predicts longevity in mice Satomi Miwa1, Howsun Jow2, Karen Baty3, Amy Johnson1, Rafal Czapiewski1, Gabriele Saretzki1, Achim Treumann3 & Thomas von Zglinicki1 Mitochondrial function is an important determinant of the ageing process; however, the mitochondrial properties that enable longevity are not well understood. Here we show that optimal assembly of mitochondrial complex I predicts longevity in mice. Using an unbiased high-coverage high-confidence approach, we demonstrate that electron transport chain proteins, especially the matrix arm subunits of complex I, are decreased in young long-living mice, which is associated with improved complex I assembly, higher complex I-linked state 3 oxygen consumption rates and decreased superoxide production, whereas the opposite is seen in old mice. Disruption of complex I assembly reduces oxidative metabolism with concomitant increase in mitochondrial superoxide production. This is rescued by knockdown of the mitochondrial chaperone, prohibitin. Disrupted complex I assembly causes premature senescence in primary cells. We propose that lower abundance of free catalytic complex I components supports complex I assembly, efficacy of substrate utilization and minimal ROS production, enabling enhanced longevity. 1 Institute for Ageing and Health, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 5PL, UK. 2 Centre for Integrated Systems Biology of Ageing and Nutrition, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 5PL, UK. 3 Newcastle University Protein and Proteome Analysis, Devonshire Building, Devonshire Terrace, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, UK. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to T.v.Z. -

Supl Table 1 for Pdf.Xlsx

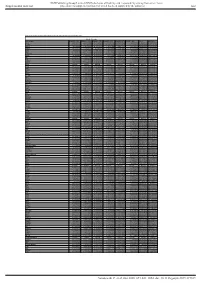

BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance Supplemental material placed on this supplemental material which has been supplied by the author(s) Gut Table S1. Proteomic analysis of liver tissues from 4-months old control and LPTENKO mice. Soluble Fraction Gene names LOG2FC CTL1 LOG2FC CTL2 LOG2FC CTL3 LOG2FC KO1 LOG2FC KO2 LOG2FC KO3 t-test adj Pvalue Aass 0.081686519 -0.097912098 0.016225579 -1.135271836 -0.860535624 -1.263037541 0.0011157 1.206072068 Acsm5 -0.125220746 0.071090866 0.054129881 -0.780692107 -0.882155692 -1.158378647 0.00189031 1.021713016 Gstm2 -0.12707966 0.572554941 -0.445475281 1.952813994 1.856518122 1.561376671 0.00517664 1.865316016 Gstm1 -0.029147714 0.298593425 -0.26944571 0.983159098 0.872028945 0.786125509 0.00721356 1.949464926 Fasn 0.08403202 -0.214149498 0.130117478 1.052480559 0.779734519 1.229308218 0.00383637 0.829422353 Upb1 -0.112438784 -0.137014769 0.249453553 -1.297732445 -1.181999331 -1.495303666 0.00102373 0.184442034 Selenbp2 0.266508271 0.084791964 -0.351300235 -2.040647809 -2.608780781 -2.039865739 0.00107121 0.165425127 Thrsp -0.15001075 0.177999342 -0.027988592 1.54283307 1.603048661 0.927443822 0.00453549 0.612858263 Hyi 0.142635733 -0.183013091 0.040377359 1.325929636 1.119934412 1.181313897 0.00044587 0.053553518 Eci1 -0.119041811 -0.014846366 0.133888177 -0.599970385 -0.555547972 -1.191875541 0.02292305 2.477981171 Aldh1a7 -0.095682449 -0.017781922 0.113464372 0.653424862 0.931724091 1.110750381 0.00356922 0.350756574 Pebp1 -0.06292058 -

Difference Between Atpase and ATP Synthase Key Difference

Difference Between ATPase and ATP Synthase www.differencebetween.com Key Difference - ATPase vs ATP Synthase Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is a complex organic molecule that participates in the biological reactions. It is known as “molecular unit of currency” of intracellular energy transfer. It is found in almost all forms of life. In the metabolism, ATP is either consumed or generated. When ATP is consumed, energy is released by converting into ADP (adenosine diphosphate) and AMP (adenosine monophosphate) respectively. The enzyme which catalyzes the following reaction is known as ATPase. ATP → ADP + Pi + Energy is released In other metabolic reactions which incorporate external energy, ATP is generated from ADP and AMP. The enzyme which catalyzes the below-mentioned reaction is called an ATP Synthase. ADP + Pi → ATP + Energy is consumed So, the key difference between ATPase and ATP Synthase is, ATPase is the enzyme that breaks down ATP molecules while the ATP Synthase involves in ATP production. What is ATPase? The ATPase or adenylpyrophosphatase (ATP hydrolase) is the enzyme which decomposes ATP molecules into ADP and Pi (free phosphate ion.) This decomposition reaction releases energy which is used by other chemical reactions in the cell. ATPases are the class of membrane-bound enzymes. They consist of a different class of members that possess unique functions such as Na+/K+-ATPase, Proton-ATPase, V-ATPase, Hydrogen Potassium–ATPase, F-ATPase, and Calcium-ATPase. These enzymes are integral transmembrane proteins. The transmembrane ATPases move solutes across the biological membrane against their concentration gradient typically by consuming the ATP molecules. So, the main functions of the ATPase enzyme family members are moving cell metabolites across the biological membrane and exporting toxins, waste and the solutes that can hinder the normal cell function.