Transient Air Dynamics Modeling for an Advanced Alternative Fueled Engine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rocket Universe 11 Structural Changes

Rocket UniVerse 11 Structural Changes What you need to know before you install or upgrade to UniVerse 11 Rocket U2 Technical Support Supplemental Information April 2014 UNV-112-REP-OG-1 Notices Edition Publication date: April 2014 Book number: UNV-112-REP-OG-1 Product version: Rocket UniVerse V11.2 Copyright © Rocket Software, Inc. or its affiliate 1985-2014. All Rights Reserved. Trademarks Rocket is a registered trademark of Rocket Software, Inc. For a list of Rocket registered trademarks go to: www.rocketsoftware.com/about/legal. All other products or services mentioned in this document may be covered by the trademarks, service marks, or product names of their respective owners. Examples This information might contain examples of data and reports. The examples include the names of individuals, companies, brands, and products. All of these names are fictitious and any similarity to the names and addresses used by an actual business enterprise is entirely coincidental. License agreement This software and the associated documentation are proprietary and confidential to Rocket Software, Inc. or its affiliates, are furnished under license, and may be used and copied only in accordance with the terms of such license. Note: This product may contain encryption technology. Many countries prohibit or restrict the use, import, or export of encryption technologies, and current use, import, and export regulations should be followed when exporting this product. Contact information Website: www.rocketsoftware.com Rocket Software, Inc. Headquarters 77 4th Avenue, Suite 100 Waltham, MA 02451-1468 USA Tel: +1 781 577 4321 Fax: +1 617 630 7100 2 Contacting Global Technical Support If you have current support and maintenance agreements with Rocket Software, you can access the Rocket Customer Portal to report and track a problem, to submit an enhancement request or question, or to find answers in the U2 Knowledgebase. -

Engine Control Unit

Engine Control Unit João Filipe Ferreira Vicente Dissertation submitted for obtaining the degree in Master of Electronic Engineering, Instituto Superior Técnico Abstract The car used (Figure 1) has a fibreglass body and uses a Honda F4i engine taken from the Honda This paper describes the design of a fully CBR 600. programmable, low cost ECU based on a standard electronic circuit based on a dsPIC30f6012A for the Honda CBR600 F4i engine used in the Formula Student IST car. The ECU must make use of all the temperature, pressure, position and speed sensors as well as the original injectors and ignition coils that are already available on the F4i engine. The ECU must provide the user access to all the maps and allow their full customization simply by connecting it to a PC. This will provide the user with Figure 1 - FST03. the capability to adjust the engine’s performance to its needs quickly and easily. II. Electronic Fuel Injection Keywords The growing concern of fuel economy and lower emissions means that Electronic Fuel Injection Electronic Fuel Injection, Engine Control Unit, (EFI) systems can be seen on most of the cars Formula Student being sold today. I. Introduction EFI systems provide comfort and reliability to the driver by ensuring a perfect engine start under This project is part of the Formula Student project most conditions while lessening the impact on the being developed at Instituto Superior Técnico that environment by lowering exhaust gas emissions for the European series of the Formula Student and providing a perfect combustion of the air-fuel competition. -

The Effect of Turbocharging on Volumetric Efficiency in Low Heat Rejection C.I. Engine Fueled with Jatrophafor Improved Performance

International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology (IJERT) ISSN: 2278-0181 Vol. 4 Issue 03, March-2015 The Effect of Turbocharging on Volumetric Efficiency in Low Heat Rejection C.I. Engine fueled with Jatrophafor Improved Performance R. Ganapathi *, Dr. B. Durga Prasad** Lecturer, Professor, Mechanical Engineering department, Mechanical Engineering department, JNTUA College of Engineering, JNTUA College of Engineering, Ananthapuramu, A.P, India. Ananthapuramu, A.P, India. burned. This can be achieved with an LHR engine dueto Abstract:- The world’s rapidly dwindling petroleum the availability of higher temperature at the time of fuel supplies, their raising cost and the growing danger of injection. The heat available due to insulation can be environmental pollution from these fuel, have some effectively used for vaporizing alternative fuel. Some substitute of conventional fuels, vegetable oils has been important advantages of the LHR engines are improved fuel considered as one of the feasible substitute to economy, reduced HC and CO emission, reduced noise due conventional fuel. Among all the fuels, tested Jatropha to lower rate of pressure rise and higher energy in the oil properties are almost closer to diesel, particularly exhaust gases [2 & 3]. However, one of the main problems cetane rating and heat value. In present work in the LHR engines is the drop in volumetric experiments are conducted with Brass Crown efficiency. This further decrease the density of air Aluminium piston with air gap, an air gap liner and entering the cylinder because of high wall temperatures of PSZ coated head and valve have been used in the the LHR engine. The degree of degradation of volumetric present study, which generates higher temperature in efficiency depends on the degree of insulation. -

Pressure Sensors

PRESSURE SENSORS Pressure Sensors Pressure sensors are used to measure intake manifold pressure, atmospheric pressure, vapor pressure in the fuel tank, etc. Though the location is different, and the pressures being measured vary, the operating principles are similar. Page 1 © Toyota Motor Sales, U.S.A., Inc. All Rights Reserved. PRESSURE SENSORS Manifold Absolute Pressure (MAP) Sensor In the Manifold Absolute Pressure (MAP) sensor there is a silicon chip mounted inside a reference chamber. On one side of the chip is a reference pressure. This reference pressure is either a perfect vacuum or a calibrated pressure, depending on the application. On the other side is the pressure to be measured. The silicon chip changes its resistance with the changes in pressure. When the silicon chip flexes with the change in pressure, the electrical resistance of the chip changes. This change in resistance alters the voltage signal. The ECM interprets the voltage signal as pressure and any change in the voltage signal means there was a change in pressure. Intake manifold pressure is a directly related to engine load. The ECM needs to know intake manifold pressure to calculate how much fuel to inject, when to ignite the cylinder, and other functions. The MAP sensor is located either directly on the intake manifold or it is mounted high in the engine compartment and connected to the intake manifold with vacuum hose. It is critical the vacuum hose not have any kinks for proper operation. Page 2 © Toyota Motor Sales, U.S.A., Inc. All Rights Reserved. PRESSURE SENSORS The MAP sensor uses a perfect vacuum as a reference pressure. -

POLESTAR Systems

POLE STAR Systems Engine Management Systems Overview: The POLE STAR HS engine management Although originally developed for the Mini A- system is a low cost yet highly sophisticated Series engine the systems can now be used on system, ranging from the basic 2D ignition-only virtually any engine including high revving system up to the full 3D Turbo Fuel Injection motorbike engines. The systems features System. include, • Supports up to 8 cylinders and 4 injector drivers • Fully sequential 4 cylinder operation supported with cam sensor • Special sequential twin-point fuel injection mode specifically designed for the A-Series engine (requires cam sensor) • Single point mode (multi-injector) • Low cost ignition only distributor-less versions also available • Direct crankshaft trigger for greater accuracy. Supports standard 36-1 trigger wheel or existing POLE STAR sensor and disk • Accurate control of ignition timing and fuelling. Timing/Fuelling adjusted with 8 load sites at every 500 rpm from 0-15000rpm with full interpolation. • Optional closed-loop fuelling with wideband lambda input • Integral ‘smooth-cut’ rev limiter • Optional ‘Boost Retard’ feature with integral MAP sensor for Turbo engines POLE STAR Systems, 31 Taskers Drive, Anna Valley, Andover, Hants, SP11 7SA web: www.polestarsystem.com Tel: 01264-333034 POLE STAR Systems depending on the system type. These are typically Details: a throttle position sensor, MAP sensor, water temperature sensor and inlet air temperature Originally developed and tested in conjunction sensor, usually the ECU canbe calibrated to use an with Bryan/Neil Slark of Slark Race Engineering engines existing temperature sensors. and Jon Lee of LynxAE using their dyno facilities. -

Marine Engine Electronics C7 –

C7 - C32 Marine Engine Electronics Application and Installation Guide APPLICATION AND INSTALLATION GUIDE MARINE ENGINE ELECTRONICS C7 – C32 Caterpillar: Confidential Yellow 1 C7 - C32 Marine Engine Electronics Application and Installation Guide 1 Introduction and Purpose…………………………………….…………………5 1.1 Safety……………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Replacement Parts…………………………………………………………….6 2 Engine System Overview……………………………………………………….7 2.1 Electronic Engine Control……………………………………………………..7 2.2 Factory Configuration Parameters……………………………………………8 2.3 Engine Component Overview…………………………………………………9 2.4 Engine Component Locations……………………………………………….12 3 Customer System Overview…………………………………………………..13 3.1 Customer Configuration Parameters……………………………………….13 3.2 Customer Component Overview…………………………………………….14 4 Power and Grounding Considerations……………………………………….15 4.1 Power Requirements…………………………………………………………15 4.2 Engine Grounding…………………………………………………………….18 4.3 Suppression of Voltage Transients…………………………………………20 4.4 Battery Disconnect Switch…………………………………………………...21 4.5 Welding on a Machine with an Electronic Engine…………………………22 5 Connectors and Wiring Harness Requirements………………………….…23 5.1 Wiring Harness Components………………………………………………..23 5.2 Wiring Harness Design………………………………………………………29 5.3 Service Tool Connector (J66) Wiring……………………………………….32 5.4 SAE J1939/ 11 - Data Bus Wiring…………………………………………..34 6 Customer Equipment I.D. and Passwords…………………………………..37 6.1 Equipment Identification……….……………………………………………..37 6.2 Customer Passwords.………………………………………………………..37 7 Factory -

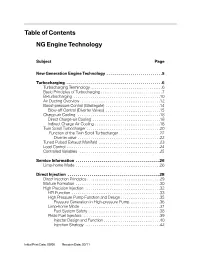

05 NG Engine Technology.Pdf

Table of Contents NG Engine Technology Subject Page New Generation Engine Technology . .5 Turbocharging . .6 Turbocharging Terminology . .6 Basic Principles of Turbocharging . .7 Bi-turbocharging . .10 Air Ducting Overview . .12 Boost-pressure Control (Wastegate) . .14 Blow-off Control (Diverter Valves) . .15 Charge-air Cooling . .18 Direct Charge-air Cooling . .18 Indirect Charge Air Cooling . .18 Twin Scroll Turbocharger . .20 Function of the Twin Scroll Turbocharger . .22 Diverter valve . .22 Tuned Pulsed Exhaust Manifold . .23 Load Control . .24 Controlled Variables . .25 Service Information . .26 Limp-home Mode . .26 Direct Injection . .28 Direct Injection Principles . .29 Mixture Formation . .30 High Precision Injection . .32 HPI Function . .33 High Pressure Pump Function and Design . .35 Pressure Generation in High-pressure Pump . .36 Limp-home Mode . .37 Fuel System Safety . .38 Piezo Fuel Injectors . .39 Injector Design and Function . .40 Injection Strategy . .42 Initial Print Date: 09/06 Revision Date: 03/11 Subject Page Piezo Element . .43 Injector Adjustment . .43 Injector Control and Adaptation . .44 Injector Adaptation . .44 Optimization . .45 HDE Fuel Injection . .46 VALVETRONIC III . .47 Phasing . .47 Masking . .47 Combustion Chamber Geometry . .48 VALVETRONIC Servomotor . .50 Function . .50 Subject Page BLANK PAGE NG Engine Technology Model: All from 2007 Production: All After completion of this module you will be able to: • Understand the technology used on BMW turbo engines • Understand basic turbocharging principles • Describe the benefits of twin Scroll Turbochargers • Understand the basics of second generation of direct injection (HPI) • Describe the benefits of HDE solenoid type direct injection • Understand the main differences between VALVETRONIC II and VALVETRONIC II I 4 NG Engine Technology New Generation Engine Technology In 2005, the first of the new generation 6-cylinder engines was introduced as the N52. -

Supercharger

Supercharger 1 4/13/2019 Supercharger Air Flow Requirements • Naturally aspirated engines with throttle bodies rely on atmospheric pressure to push an air–fuel mixture into the combustion chamber vacuum created by the down stroke of a piston. • The mixture is then compressed before ignition to increase the force of the burning, expanding gases. • The greater the mixture compression, the greater the power resulting from combustion. Engineers calculate engine airflow requirements using these three factors: – Engine displacement – Engine revolutions per minute (RPM) – Volumetric efficiency Volumetric efficiency – is a comparison of the actual volume of air–fuel mixture drawn into an engine to the theoretical maximum volume that could be drawn in. – Volumetric efficiency decreases as engine speed increases. 2 4/13/2019 Supercharger Principles of Power Increase: The power output of the engine depend up on the amount of air induced per unit time and thermal efficiency. The amount of air induced per unit time can be increased by: Increasing the engine speed. the increase in engine speed calls for rigid and robust engine as the inertia load increase also the engine fraction and bearing load increase and also the volumetric efficiency decrease. Increasing the density of air at inlet. The increase of inlet air density calls supercharging which usually used to increase the power output from engine due to increase the air pressure at the inlet of engine. 3 4/13/2019 Supercharger The Objects of Supercharging: To increase the power output for a given weight and bulk of the engine. This is important for aircraft, marine and automotive engines where weight and space are important. -

Design of the Electronic Engine Control Unit Performance Test System of Aircraft

aerospace Article Design of the Electronic Engine Control Unit Performance Test System of Aircraft Seonghee Kho 1 and Hyunbum Park 2,* 1 Department of Defense Science & Technology-Aeronautics, Howon University, 64 Howondae 3gil, Impi, Gunsan 54058, Korea; [email protected] 2 School of Mechanical Convergence System Engineering, Kunsan National University, 558 Daehak-ro, Miryong-dong, Gunsan 54150, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-(0)63-469-4729 Abstract: In this study, a real-time engine model and a test bench were developed to verify the performance of the EECU (electronic engine control unit) of a turbofan engine. The target engine is a DGEN 380 developed by the Price Induction company. The functional verification of the test bench was carried out using the developed test bench. An interface and interworking test between the test bench and the developed EECU was carried out. After establishing the verification test environments, the startup phase control logic of the developed EECU was verified using the real- time engine model which modeled the startup phase test data with SIMULINK. Finally, it was confirmed that the developed EECU can be used as a real-time engine model for the starting section of performance verification. Keywords: test bench; EECU (electronic engine control unit); turbofan engine Citation: Kho, S.; Park, H. Design of 1. Introduction the Electronic Engine Control Unit The EECU is a very important component in aircraft engines, and the verification Performance Test System of Aircraft. test for numerous items should be carried out in its development process. Since it takes Aerospace 2021, 8, 158. https:// a lot of time and cost to carry out such verification test using an actual engine, and an doi.org/10.3390/aerospace8060158 expensive engine may be damaged or a safety hazard may occur, the simulator which virtually generates the same signals with the actual engine is essential [1]. -

Developments in Precision Power Train Sensors

109 Hitachi Review Vol. 63 (2014), No. 2 Developments in Precision Power Train Sensors Keiji Hanzawa OVERVIEW: The fuel economy and emissions performance demands on Shinobu Tashiro vehicle power trains are becoming more stringent for reasons relating Hiroaki Hoshika to global environmental protection and the rising price of oil. There has also been a change in thinking on the measurement of emissions and Masahiro Matsumoto fuel economy toward allowing for conditions where the temperature and humidity are closer to real driving conditions. Other changes include the electrifi cation of power trains, such as in hybrid vehicles, and improvements in the running effi ciency of internal combustion engines that result in more frequent use of engine operating modes in which sensor operation is more diffi cult, such as the Atkinson cycle. Hitachi Automotive Systems, Ltd. is supporting ongoing progress in power train control by making further improvements in sensor accuracy. INTRODUCTION Automotive power trains have made rapid progress HITACHI supplies customers around the world with on electrifi cation and reducing fuel consumption in a variety of systems for the driving, cornering, and recent years. This article describes advances in the braking of vehicles. By using a range of different performance of the sensors used in these power trains, sensors to determine conditions in the power train, looking at micro electromechanical system (MEMS) vehicle body movements, and what is happening air fl ow sensors that reduce the error in intake pulsation, around the vehicle, these systems ensure a driving the integration of air intake relative humidity sensors experience that is safe and comfortable, and that is and pressure sensors, and the adoption of digital signal conscious of the global environment (see Fig. -

Air Filter Sizing

SSeeccoonndd SSttrriikkee The Newsletter for the Superformance Owners Group January 17, 2008 / September 5, 2011 Volume 8, Number 1 SECOND STRIKE CARBURETOR CALCULATOR The Carburetor Controlling the airflow introduces the throttle plate assembly. Metering the fuel requires measuring the airflow and measuring the airflow introduces the venturi. Metering the fuel flow introduces boosters. The high flow velocity requirement constrains the size of the air passages. These obstructions cause a pressure drop, a necessary consequence of proper carburetor function. Carburetors are sized by airflow, airflow at 5% pressure drop for four-barrels, 10% for two-barrels. This means that the price for a properly sized four-barrel is a 5% pressure loss and a corresponding 5% horsepower loss. The important thing to remember is that carburetors are sized to provide balanced performance across the entire driving range, not just peak horsepower. When designing low and mid range metering, the carburetor engineers assume airflow conditions for a properly As with everything in the engine, airflow is power. sized carburetor - one sized for 5% loss at the power peak. Carburetors are a key to airflow. As with any component, the key to best all around performance is to pick parts that match Selecting a larger carburetor than recommended will reduce your performance goal and each other – carburetor, intake, pressure losses at high rpm and may help top end horsepower, heads, exhaust, cam, displacement, rpm range, and bottom but will have lower flow velocity at low rpm and poor end. metering and mixing with a loss in low and mid range power and drivability. -

A Soft Linen Emulsion Rate Intelligent Control System Based on the Domain Interpolation Algorithm with Self Adjusting

JOURNAL OF SOFTWARE, VOL. 6, NO. 8, AUGUST 2011 1429 A Soft Linen Emulsion Rate Intelligent Control System Based on the Domain Interpolation Algorithm with Self Adjusting Xiao Ying Jinggangshan University / school of Electronic and Information Engineering, Ji’an, Jiangxi ,China 343009 [email protected] Peng Xuange Jinggangshan University / school of Electronic and Information Engineering, Ji’an, Jiangxi ,China 343009 [email protected] Abstract—A soft linen emulsion rate intelligent control linen and ramie is called as soft linen, including system based on the domain interpolation algorithm with mechanical soft linen, fuel, wet and storage. The purpose self adjusting is introduced. In the hemp textile industry, is to enable fiber loose, soft, surface lubrication, remove soft linen deal processes can directly affect its following some impurities and then fermented by the heap storage process. We take the lead to use the fuzzy control method to improve the fiber spin ability, then carding and applied in soft linen emulsion rate of Intelligent Control System. In the research process, the improvement of spinning can be carried out. This process quality has the product quality is not satisfied by basic fuzzy control direct impact on the following process, such as the method. By improving the algorithm, combined advanced quality of spinning and weaving. interpolation algorithm into fuzzy decision process, that The references show that the world, especially experience rule set has no restriction to access control list, Southeast Asia, in hemp textile the soft linen processes enhanced the flexibility of the method, and obtain fine are used the same fall behind technology model, that is enough fuzzy control table under the same rules.