Fecal Microbiota Transplantation: an Interest in IBD?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Administering Unidata on UNIX Platforms

C:\Program Files\Adobe\FrameMaker8\UniData 7.2\7.2rebranded\ADMINUNIX\ADMINUNIXTITLE.fm March 5, 2010 1:34 pm Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta UniData Administering UniData on UNIX Platforms UDT-720-ADMU-1 C:\Program Files\Adobe\FrameMaker8\UniData 7.2\7.2rebranded\ADMINUNIX\ADMINUNIXTITLE.fm March 5, 2010 1:34 pm Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Beta Notices Edition Publication date: July, 2008 Book number: UDT-720-ADMU-1 Product version: UniData 7.2 Copyright © Rocket Software, Inc. 1988-2010. All Rights Reserved. Trademarks The following trademarks appear in this publication: Trademark Trademark Owner Rocket Software™ Rocket Software, Inc. Dynamic Connect® Rocket Software, Inc. RedBack® Rocket Software, Inc. SystemBuilder™ Rocket Software, Inc. UniData® Rocket Software, Inc. UniVerse™ Rocket Software, Inc. U2™ Rocket Software, Inc. U2.NET™ Rocket Software, Inc. U2 Web Development Environment™ Rocket Software, Inc. wIntegrate® Rocket Software, Inc. Microsoft® .NET Microsoft Corporation Microsoft® Office Excel®, Outlook®, Word Microsoft Corporation Windows® Microsoft Corporation Windows® 7 Microsoft Corporation Windows Vista® Microsoft Corporation Java™ and all Java-based trademarks and logos Sun Microsystems, Inc. UNIX® X/Open Company Limited ii SB/XA Getting Started The above trademarks are property of the specified companies in the United States, other countries, or both. All other products or services mentioned in this document may be covered by the trademarks, service marks, or product names as designated by the companies who own or market them. License agreement This software and the associated documentation are proprietary and confidential to Rocket Software, Inc., are furnished under license, and may be used and copied only in accordance with the terms of such license and with the inclusion of the copyright notice. -

Text Processing Tools

Tools for processing text David Morgan Tools of interest here sort paste uniq join xxd comm tr fmt sed fold head file tail dd cut strings 1 sort sorts lines by default can delimit fields in lines ( -t ) can sort by field(s) as key(s) (-k ) can sort fields of numerals numerically ( -n ) Sort by fields as keys default sort sort on shell (7 th :-delimited) field UID as secondary (tie-breaker) field 2 Do it numerically versus How sort defines text ’s “fields ” by default ( a space character, ascii 32h = ٠ ) ٠bar an 8-character string ٠foo “By default, fields are separated by the empty string between a non-blank character and a blank character.” ٠bar separator is the empty string between non-blank “o” and the space ٠foo 1 2 ٠bar and the string has these 2 fields, by default ٠foo 3 How sort defines text ’s “fields ” by –t specification (not default) ( a space character, ascii 32h = ٠ ) ٠bar an 8-character string ٠foo “ `-t SEPARATOR' Use character SEPARATOR as the field separator... The field separator is not considered to be part of either the field preceding or the field following ” separators are the blanks themselves, and fields are ' "٠ " ٠bar with `sort -t ٠foo whatever they separate 12 3 ٠bar and the string has these 3 fields ٠foo data sort fields delimited by vertical bars field versus sort field ("1941:japan") ("1941") 4 sort efficiency bubble sort of n items, processing grows as n 2 shell sort as n 3/2 heapsort/mergesort/quicksort as n log n technique matters sort command highly evolved and optimized – better than you could do it yourself Big -O: " bogdown propensity" how much growth requires how much time 5 sort stability stable if input order of key-equal records preserved in output unstable if not sort is not stable GNU sort has –stable option sort stability 2 outputs, from same input (all keys identical) not stable stable 6 uniq operates on sorted input omits repeated lines counts them uniq 7 xxd make hexdump of file or input your friend testing intermediate pipeline data cf. -

QLOAD Queue Load / Unload Utility for IBM MQ

Queue Load / Unload Utility for IBM MQ User Guide Version 9.1.1 27th August 2020 Paul Clarke MQGem Software Limited [email protected] Queue Load / Unload Utility for IBM MQ Take Note! Before using this User's Guide and the product it supports, be sure to read the general information under "Notices” Twenty-fourth Edition, August 2020 This edition applies to Version 9.1.1 of Queue Load / Unload Utility for IBM MQ and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. (c) Copyright MQGem Software Limited 2015, 2020. All rights reserved. ii Queue Load / Unload Utility for IBM MQ Notices The following paragraph does not apply in any country where such provisions are inconsistent with local law. MQGEM SOFTWARE LIMITED PROVIDES THIS PUBLICATION "AS IS" WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EITHER EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, BUT NOT LIMITED TO, THE IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. Some states do not allow disclaimer of express or implied warranties in certain transactions, therefore this statement may not apply to you. The information contained in this document has not be submitted to any formal test and is distributed AS IS. The use of the information or the implementation of any of these techniques is a customer responsibility and depends on the customer's ability to evaluate and integrate them into the customer's operational environment. While each item has been reviewed by MQGem Software for accuracy in a specific situation, there is no guarantee that the same or similar results will be obtained elsewhere. -

From Donor to Patient: Collection, Preparation and Cryopreservation of Fecal Samples for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation

diseases Review From Donor to Patient: Collection, Preparation and Cryopreservation of Fecal Samples for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Carole Nicco 1 , Armelle Paule 2, Peter Konturek 3 and Marvin Edeas 1,* 1 Cochin Institute, INSERM U1016, University Paris Descartes, Development, Reproduction and Cancer, Cochin Hospital, 75014 Paris, France; [email protected] 2 International Society of Microbiota, 75002 Paris, France; [email protected] 3 Teaching Hospital of the University of Jena, Thuringia-Clinic Saalfeld, 07318 Saalfeld, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 6 March 2020; Accepted: 10 April 2020; Published: 15 April 2020 Abstract: Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) is suggested as an efficacious therapeutic strategy for restoring intestinal microbial balance, and thus for treating disease associated with alteration of gut microbiota. FMT consists of the administration of fresh or frozen fecal microorganisms from a healthy donor into the intestinal tract of diseased patients. At this time, in according to healthcare authorities, FMT is mainly used to treat recurrent Clostridium difficile. Despite the existence of a few existing stool banks worldwide and many studies of the FMT, there is no standard method for producing material for FMT, and there are a multitude of factors that can vary between the institutions. The main constraints for the therapeutic uses of FMT are safety concerns and acceptability. Technical and logistical issues arise when establishing such a non-standardized treatment into clinical practice with safety and proper governance. In this context, our manuscript describes a process of donor safety screening for FMT compiling clinical and biological examinations, questionnaires and interviews of donors. -

A Type System for Format Strings E

ifact t * r * Comple t te A A n * te W E is s * e C n l l o D C A o * * c T u e m S s E u e S e n I R t v A Type System for Format Strings e o d t y * s E a * a l d u e a t Konstantin Weitz Gene Kim Siwakorn Srisakaokul Michael D. Ernst University of Washington, USA {weitzkon,genelkim,ping128,mernst}@cs.uw.edu ABSTRACT // Untested code (Hadoop) Most programming languages support format strings, but their use Resource r = ... format("Insufficient memory %d", r); is error-prone. Using the wrong format string syntax, or passing the wrong number or type of arguments, leads to unintelligible text // Unchecked input (FindBugs) output, program crashes, or security vulnerabilities. String urlRewriteFormat = read(); This paper presents a type system that guarantees that calls to format(urlRewriteFormat, url); format string APIs will never fail. In Java, this means that the API will not throw exceptions. In C, this means that the API will not // User unaware log is a format routine (Daikon) log("Exception " + e); return negative values, corrupt memory, etc. We instantiated this type system for Java’s Formatter API, and // Invalid syntax for Formatter API (ping-gcal) evaluated it on 6 large and well-maintained open-source projects. format("Unable to reach {0}", server); Format string bugs are common in practice (our type system found Listing 1: Real-world code examples of common programmer 104 bugs), and the annotation burden on the user of our type system mistakes that lead to format routine call failures. -

Some UNIX Commands At

CTEC1863/2007F Operating Systems – UNIX Commands Some UNIX Commands at Syntax: at time [day] [file] Description: Provides ability to perform UNIX commands at some time in the future. At time time on day day, the commands in filefile will be executed. Comment: Often used to do time-consuming work during off-peak hours, or to remind yourself to do something during the day. Other at-related commands: atq - Dump the contents of the at event queue. atrm - Remove at jobs from the queue. Examples: # at 0300 calendar | mail john ^D # # cat > DOTHIS nroff -ms doc1 >> doc.fmt nroff -ms file2 >> doc.fmt spell doc.fmt > SPELLerrs ^D # at 0000 DOTHIS cal Syntax: cal [month] year Description: Prints a calendar for the specified year or month. The year starts from year 0 [the calendar switched to Julian in 1752], so you typically must include the century Comment: Typical syntax: cal 11 1997 cal 1998 /Users/mboldin/2007F/ctec1863/unixnotes/UNIX-07_Commands.odt Page 1 of 5 CTEC1863/2007F Operating Systems – UNIX Commands calendar Syntax: calendar [-] Description: You must set-up a file, typically in your home directory, called calendar. This is a database of events. Comment: Each event must have a date mentioned in it: Sept 10, 12/5, Aug 21 1998, ... Each event scheduled for the day or the next day will be listed on the screen. lpr Syntax: lpr [OPTIONS] [FILE] [FILE] ... Description: The files are queued to be output to the printer. Comment: On some UNIX systems, this command is called lp, with slightly different options. Both lpr and lp first make a copy of the file(s) to be printed in the spool directory. -

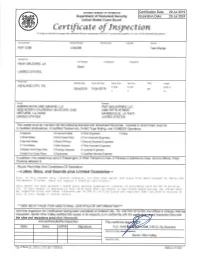

Certific at E of Insy Ection

United States of America Department of Homeland Security United States Coast Guard Certific at e of Insy ection For ships on international voyages this certificate fulfills the requirements of SOLAS 74 as amended, regulation V/1 4, for a SAFE MANNING DOCUI\,4ENT Vessel Name Official Number IMO Number Call Sign Service FMT 3298 1294599 Tank Barge Hailing Port Hull l,4aterial Horsepower Propulsion NEW ORLEANS, LA Steel UNITED STATES Place Built Deliwry Date Keel Laid Date Gross Tons Net Tons DWT Length ASHLAND CITY, TN R-1619 R-1 6 13 R-297.5 29Ju12019 14Jun2019 894 t- t- t-0 Owner Operator AMERICAN INLAND MARINE LLC FMT INDUSTRIES LLC 3838 NORTH CAUSEWAY BLVD STE 3335 2360 FIFTH STREET METAIRIE, LA 7OOO2 MANDEVILLE, LA70471 UNITED STATES UNITED STATES This vessel must be manned with the following licensed and unlicensed Personnel. lncluded in which there must be 0 Certified Lifeboatmen, 0 Certified Tankermen, 0 HSC Type Rating, and 0 GMDSS Operators. 0 Masters 0 Licensed Mates 0 Chief Engineers 0 Oilers 0 Chief Mates 0 First Class Pilots 0 First Assistant Engineers 0 Second Mates 0 Radio Officers 0 Second Assistant Engineers 0 Third Mates 0 Able Seamen 0 Third Assistant Engineers 0 Master First Class Pilot 0 Ordinary Seamen 0 Licensed Engineers 0 Mate First Class Pilots 0 Deckhands 0 Qualified Member Engineer ln addition, this vessel may carry 0 Passengers, 0 Other Persons in crew, 0 Persons in addition to crew, and no Others. Total Persons allowed:0 Route Permitted And Conditions Of Operation: ---Lakes, Bays, and Sounds plus Limited Coastwise-- Also, in fair weather only, linited coastwise, not more than twelve (12) mifes from shore between St. -

(TBUT) and Schirmer’S Tests (ST) in the Diagnosis of Dry Eyes

Eye (2002) 16, 594–600 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-222X/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/eye GU Kallarackal1, EA Ansari2, N Amos1, CLINICAL STUDY A comparative study JC Martin3, C Lane2 and JP Camilleri1 to assess the clinical use of Fluorescein Meniscus Time (FMT) with Tear Break up Time (TBUT) and Schirmer’s tests (ST) in the diagnosis of dry eyes Abstract and control populations; Mann–Whitney P Ͻ Introduction The clinical diagnosis of dry- 0.001. There was a correlation between the eye is confirmed by a suitable test of tear right and left eye for all three tests in the 2 = 2 = production and the technique commonly control group (ST r 0.77, FMT r 0.98, 2 = used today to diagnose dry eye is the TBUT r 0.94). This correlation was Schirmer’s test (ST). Although the ST is easy markedly reduced for FMT and TBUT in the to perform it gives variable results, poor patient population and was in keeping with reproducibility and low sensitivity for the symptoms reported as being worse on detecting dry eyes. Another test, the tear one side in a proportion of the patients 2 = 2 = 2 = break up time (TBUT) is used to assess the (FMT r 0.52, TBUT r 0.54, ST r 0.75). stability of tears which if abnormal may also A correlation with age was also observed for 2 cause symptomatic dry-eye. We present the all the three tests in the control group (ST r = 2 = 2 = results of both these tests and a new test, 0.74, FMT r 0.92, TBUT r 0.51), but 2 = which shows greater sensitivity than the ST not in the patient population (ST r 0.06, 1 2 = 2 = Department of in detecting aqueous tear deficiency. -

301 Part 655—Temporary Employ

Employment and Training Administration, Labor Pt. 655 must be in proper proportion to the ca- maintained in accordance with applica- pacity of the housing and must be sepa- ble State or local fire and safety laws. rate from the sleeping quarters. The (b) In family housing and housing physical facilities, equipment, and op- units for less than 10 persons, of one eration must be in accordance with story construction, two means of es- provisions of applicable State codes. cape must be provided. One of the two (d) Wall surface adjacent to all food required means of escape may be a preparation and cooking areas must be readily accessible window with an of nonabsorbent, easily cleaned mate- openable space of not less than 24 × 24 rial. In addition, the wall surface adja- inches. cent to cooking areas must be of fire- (c) All sleeping quarters intended for resistant material. use by 10 or more persons, central din- § 654.414 Garbage and other refuse. ing facilities, and common assembly rooms must have at least two doors re- (a) Durable, fly-tight, clean con- motely separated so as to provide al- tainers in good condition of a min- ternate means of escape to the outside imum capacity of 20 gallons, must be or to an interior hall. provided adjacent to each housing unit for the storage of garbage and other (d) Sleeping quarters and common as- refuse. Such containers must be pro- sembly rooms on the second story must vided in a minimum ratio of 1 per 15 have a stairway, and a permanent, af- persons. -

Gnu Coreutils Core GNU Utilities for Version 6.9, 22 March 2007

gnu Coreutils Core GNU utilities for version 6.9, 22 March 2007 David MacKenzie et al. This manual documents version 6.9 of the gnu core utilities, including the standard pro- grams for text and file manipulation. Copyright c 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, with no Front-Cover Texts, and with no Back-Cover Texts. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License". Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1 Introduction This manual is a work in progress: many sections make no attempt to explain basic concepts in a way suitable for novices. Thus, if you are interested, please get involved in improving this manual. The entire gnu community will benefit. The gnu utilities documented here are mostly compatible with the POSIX standard. Please report bugs to [email protected]. Remember to include the version number, machine architecture, input files, and any other information needed to reproduce the bug: your input, what you expected, what you got, and why it is wrong. Diffs are welcome, but please include a description of the problem as well, since this is sometimes difficult to infer. See section \Bugs" in Using and Porting GNU CC. This manual was originally derived from the Unix man pages in the distributions, which were written by David MacKenzie and updated by Jim Meyering. -

Netapp XCP V1.6 User Guide

XCP v1.6 User Guide April 2020 | 215-14881_A0 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 XCP Overview .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Software and Licensing ............................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 XCP Host System Requirements ............................................................................................................. 5 1.3 XCP File Analytics System Requirements ................................................................................................ 6 2 XCP NFS ........................................................................................................................................... 7 3 XCP NFS Installation ....................................................................................................................... 9 4 XCP NFS Command Reference .................................................................................................... 11 4.1 help ........................................................................................................................................................ 13 4.2 show ....................................................................................................................................................... 20 4.3 License .................................................................................................................................................. -

GPL-3-Free Replacements of Coreutils 1 Contents

GPL-3-free replacements of coreutils 1 Contents 2 Coreutils GPLv2 2 3 Alternatives 3 4 uutils-coreutils ............................... 3 5 BSDutils ................................... 4 6 Busybox ................................... 5 7 Nbase .................................... 5 8 FreeBSD ................................... 6 9 Sbase and Ubase .............................. 6 10 Heirloom .................................. 7 11 Replacement: uutils-coreutils 7 12 Testing 9 13 Initial test and results 9 14 Migration 10 15 Due to the nature of Apertis and its target markets there are licensing terms that 1 16 are problematic and that forces the project to look for alternatives packages. 17 The coreutils package is good example of this situation as its license changed 18 to GPLv3 and as result Apertis cannot provide it in the target repositories and 19 images. The current solution of shipping an old version which precedes the 20 license change is not tenable in the long term, as there are no upgrades with 21 bugfixes or new features for such important package. 22 This situation leads to the search for a drop-in replacement of coreutils, which 23 need to provide compatibility with the standard GNU coreutils packages. The 24 reason behind is that many other packages rely on the tools it provides, and 25 failing to do that would lead to hard to debug failures and many custom patches 26 spread all over the archive. In this regard the strict requirement is to support 27 the features needed to boot a target image with ideally no changes in other 28 components. The features currently available in our coreutils-gplv2 fork are a 29 good approximation. 30 Besides these specific requirements, the are general ones common to any Open 31 Source Project, such as maturity and reliability.