E P I C a S E C R I T E R I a Guide, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

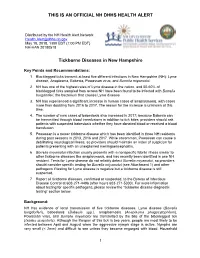

Official Nh Dhhs Health Alert

THIS IS AN OFFICIAL NH DHHS HEALTH ALERT Distributed by the NH Health Alert Network [email protected] May 18, 2018, 1300 EDT (1:00 PM EDT) NH-HAN 20180518 Tickborne Diseases in New Hampshire Key Points and Recommendations: 1. Blacklegged ticks transmit at least five different infections in New Hampshire (NH): Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Babesia, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi. 2. NH has one of the highest rates of Lyme disease in the nation, and 50-60% of blacklegged ticks sampled from across NH have been found to be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. 3. NH has experienced a significant increase in human cases of anaplasmosis, with cases more than doubling from 2016 to 2017. The reason for the increase is unknown at this time. 4. The number of new cases of babesiosis also increased in 2017; because Babesia can be transmitted through blood transfusions in addition to tick bites, providers should ask patients with suspected babesiosis whether they have donated blood or received a blood transfusion. 5. Powassan is a newer tickborne disease which has been identified in three NH residents during past seasons in 2013, 2016 and 2017. While uncommon, Powassan can cause a debilitating neurological illness, so providers should maintain an index of suspicion for patients presenting with an unexplained meningoencephalitis. 6. Borrelia miyamotoi infection usually presents with a nonspecific febrile illness similar to other tickborne diseases like anaplasmosis, and has recently been identified in one NH resident. Tests for Lyme disease do not reliably detect Borrelia miyamotoi, so providers should consider specific testing for Borrelia miyamotoi (see Attachment 1) and other pathogens if testing for Lyme disease is negative but a tickborne disease is still suspected. -

The Role of Streptococcal and Staphylococcal Exotoxins and Proteases in Human Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections

toxins Review The Role of Streptococcal and Staphylococcal Exotoxins and Proteases in Human Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections Patience Shumba 1, Srikanth Mairpady Shambat 2 and Nikolai Siemens 1,* 1 Center for Functional Genomics of Microbes, Department of Molecular Genetics and Infection Biology, University of Greifswald, D-17489 Greifswald, Germany; [email protected] 2 Division of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology, University Hospital Zurich, University of Zurich, CH-8091 Zurich, Switzerland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-3834-420-5711 Received: 20 May 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 11 June 2019 Abstract: Necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTIs) are critical clinical conditions characterized by extensive necrosis of any layer of the soft tissue and systemic toxicity. Group A streptococci (GAS) and Staphylococcus aureus are two major pathogens associated with monomicrobial NSTIs. In the tissue environment, both Gram-positive bacteria secrete a variety of molecules, including pore-forming exotoxins, superantigens, and proteases with cytolytic and immunomodulatory functions. The present review summarizes the current knowledge about streptococcal and staphylococcal toxins in NSTIs with a special focus on their contribution to disease progression, tissue pathology, and immune evasion strategies. Keywords: Streptococcus pyogenes; group A streptococcus; Staphylococcus aureus; skin infections; necrotizing soft tissue infections; pore-forming toxins; superantigens; immunomodulatory proteases; immune responses Key Contribution: Group A streptococcal and Staphylococcus aureus toxins manipulate host physiological and immunological responses to promote disease severity and progression. 1. Introduction Necrotizing soft tissue infections (NSTIs) are rare and represent a more severe rapidly progressing form of soft tissue infections that account for significant morbidity and mortality [1]. -

Naeglaria and Brain Infections

Can bacteria shrink tumors? Cancer Therapy: The Microbial Approach n this age of advanced injected live Streptococcus medical science and into cancer patients but after I technology, we still the recipients unfortunately continue to hunt for died from subsequent innovative cancer therapies infections, Coley decided to that prove effective and safe. use heat killed bacteria. He Treatments that successfully made a mixture of two heat- eradicate tumors while at the killed bacterial species, By Alan Barajas same time cause as little Streptococcus pyogenes and damage as possible to normal Serratia marcescens. This Alani Barajas is a Research and tissue are the ultimate goal, concoction was termed Development Technician at Hardy but are also not easy to find. “Coley’s toxins.” Bacteria Diagnostics. She earned her bachelor's degree in Microbiology at were either injected into Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo. The use of microorganisms in tumors or into the cancer therapy is not a new bloodstream. During her studies at Cal Poly, much idea but it is currently a of her time was spent as part of the undergraduate research team for the buzzing topic in cancer Cal Poly Dairy Products Technology therapy research. Center studying spore-forming bacteria in dairy products. In the late 1800s, German Currently she is working on new physicians W. Busch and F. chromogenic media formulations for Fehleisen both individually Hardy Diagnostics, both in the observed that certain cancers prepared and powdered forms. began to regress when patients acquired accidental erysipelas (cellulitis) caused by Streptococcus pyogenes. William Coley was the first to use New York surgeon William bacterial injections to treat cancer www.HardyDiagnostics.com patients. -

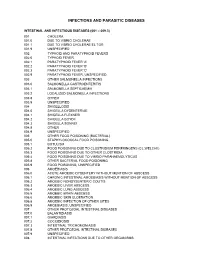

Diagnostic Code Descriptions (ICD9)

INFECTIONS AND PARASITIC DISEASES INTESTINAL AND INFECTIOUS DISEASES (001 – 009.3) 001 CHOLERA 001.0 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE 001.1 DUE TO VIBRIO CHOLERAE EL TOR 001.9 UNSPECIFIED 002 TYPHOID AND PARATYPHOID FEVERS 002.0 TYPHOID FEVER 002.1 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'A' 002.2 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'B' 002.3 PARATYPHOID FEVER 'C' 002.9 PARATYPHOID FEVER, UNSPECIFIED 003 OTHER SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.0 SALMONELLA GASTROENTERITIS 003.1 SALMONELLA SEPTICAEMIA 003.2 LOCALIZED SALMONELLA INFECTIONS 003.8 OTHER 003.9 UNSPECIFIED 004 SHIGELLOSIS 004.0 SHIGELLA DYSENTERIAE 004.1 SHIGELLA FLEXNERI 004.2 SHIGELLA BOYDII 004.3 SHIGELLA SONNEI 004.8 OTHER 004.9 UNSPECIFIED 005 OTHER FOOD POISONING (BACTERIAL) 005.0 STAPHYLOCOCCAL FOOD POISONING 005.1 BOTULISM 005.2 FOOD POISONING DUE TO CLOSTRIDIUM PERFRINGENS (CL.WELCHII) 005.3 FOOD POISONING DUE TO OTHER CLOSTRIDIA 005.4 FOOD POISONING DUE TO VIBRIO PARAHAEMOLYTICUS 005.8 OTHER BACTERIAL FOOD POISONING 005.9 FOOD POISONING, UNSPECIFIED 006 AMOEBIASIS 006.0 ACUTE AMOEBIC DYSENTERY WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.1 CHRONIC INTESTINAL AMOEBIASIS WITHOUT MENTION OF ABSCESS 006.2 AMOEBIC NONDYSENTERIC COLITIS 006.3 AMOEBIC LIVER ABSCESS 006.4 AMOEBIC LUNG ABSCESS 006.5 AMOEBIC BRAIN ABSCESS 006.6 AMOEBIC SKIN ULCERATION 006.8 AMOEBIC INFECTION OF OTHER SITES 006.9 AMOEBIASIS, UNSPECIFIED 007 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.0 BALANTIDIASIS 007.1 GIARDIASIS 007.2 COCCIDIOSIS 007.3 INTESTINAL TRICHOMONIASIS 007.8 OTHER PROTOZOAL INTESTINAL DISEASES 007.9 UNSPECIFIED 008 INTESTINAL INFECTIONS DUE TO OTHER ORGANISMS -

“Candidatus Deianiraea Vastatrix” with the Ciliate Paramecium Suggests

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/479196; this version posted November 27, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The extracellular association of the bacterium “Candidatus Deianiraea vastatrix” with the ciliate Paramecium suggests an alternative scenario for the evolution of Rickettsiales 5 Castelli M.1, Sabaneyeva E.2, Lanzoni O.3, Lebedeva N.4, Floriano A.M.5, Gaiarsa S.5,6, Benken K.7, Modeo L. 3, Bandi C.1, Potekhin A.8, Sassera D.5*, Petroni G.3* 1. Centro Romeo ed Enrica Invernizzi Ricerca Pediatrica, Dipartimento di Bioscienze, Università 10 degli studi di Milano, Milan, Italy 2. Department of Cytology and Histology, Faculty of Biology, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint-Petersburg, Russia 3. Dipartimento di Biologia, Università di Pisa, Pisa, Italy 4 Centre of Core Facilities “Culture Collections of Microorganisms”, Saint Petersburg State 15 University, Saint Petersburg, Russia 5. Dipartimento di Biologia e Biotecnologie, Università degli studi di Pavia, Pavia, Italy 6. UOC Microbiologia e Virologia, Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy 7. Core Facility Center for Microscopy and Microanalysis, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint- Petersburg, Russia 20 8. Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Biology, Saint Petersburg State University, Saint- Petersburg, Russia * Corresponding authors, contacts: [email protected] ; [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/479196; this version posted November 27, 2018. -

Fleas and Flea-Borne Diseases

International Journal of Infectious Diseases 14 (2010) e667–e676 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Infectious Diseases journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ijid Review Fleas and flea-borne diseases Idir Bitam a, Katharina Dittmar b, Philippe Parola a, Michael F. Whiting c, Didier Raoult a,* a Unite´ de Recherche en Maladies Infectieuses Tropicales Emergentes, CNRS-IRD UMR 6236, Faculte´ de Me´decine, Universite´ de la Me´diterrane´e, 27 Bd Jean Moulin, 13385 Marseille Cedex 5, France b Department of Biological Sciences, SUNY at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA c Department of Biology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA ARTICLE INFO SUMMARY Article history: Flea-borne infections are emerging or re-emerging throughout the world, and their incidence is on the Received 3 February 2009 rise. Furthermore, their distribution and that of their vectors is shifting and expanding. This publication Received in revised form 2 June 2009 reviews general flea biology and the distribution of the flea-borne diseases of public health importance Accepted 4 November 2009 throughout the world, their principal flea vectors, and the extent of their public health burden. Such an Corresponding Editor: William Cameron, overall review is necessary to understand the importance of this group of infections and the resources Ottawa, Canada that must be allocated to their control by public health authorities to ensure their timely diagnosis and treatment. Keywords: ß 2010 International Society for Infectious Diseases. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Flea Siphonaptera Plague Yersinia pestis Rickettsia Bartonella Introduction to 16 families and 238 genera have been described, but only a minority is synanthropic, that is they live in close association with The past decades have seen a dramatic change in the geographic humans (Table 1).4,5 and host ranges of many vector-borne pathogens, and their diseases. -

Rickettsia Felis: Molecular Characterization of a New Member of the Spotted Fever Group

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2001), 51, 339–347 Printed in Great Britain Rickettsia felis: molecular characterization of a new member of the spotted fever group Donald H. Bouyer,1 John Stenos,2 Patricia Crocquet-Valdes,1 Cecilia G. Moron,1 Vsevolod L. Popov,1 Jorge E. Zavala-Velazquez,3 Lane D. Foil,4 Diane R. Stothard,5 Abdu F. Azad6 and David H. Walker1 Author for correspondence: David H. Walker. Tel: j1 409 772 2856. Fax: j1 409 772 2500. e-mail: dwalker!utmb.edu 1 Department of Pathology, In this report, placement of Rickettsia felis in the spotted fever group (SFG) WHO Collaborating Center rather than the typhus group (TG) of Rickettsia is proposed. The organism, for Tropical Diseases, University of Texas Medical which was first observed in cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis) by electron Branch, 301 University microscopy, has not yet been reported to have been cultivated reproducibly, Blvd, Galveston, TX thereby limiting the standard rickettsial typing by serological means. To 77555-0609, USA overcome this challenge, several genes were selected as targets to be utilized 2 Australian Rickettsial for the classification of R. felis. DNA from cat fleas naturally infected with R. Reference Laboratory, Douglas Hocking Medical felis was amplified by PCR utilizing primer sets specific for the 190 kDa surface Institute, Geelong antigen (rOmpA) and 17 kDa antigen genes. The entire 5513 bp rompA gene Hospital, Geelong, was sequenced, characterized and found to have several unique features when Australia compared to the rompA genes of other Rickettsia. Phylogenetic analysis of the 3 Department of Tropical partial sequence of the 17 kDa antigen gene indicated that R. -

Scarlet Fever Fact Sheet

Scarlet Fever Fact Sheet Scarlet fever is a rash illness caused by a bacterium called Group A Streptococcus (GAS) The disease most commonly occurs with GAS pharyngitis (“strep throat”) [See also Strep Throat fact sheet]. Scarlet fever can occur at any age, but it is most frequent among school-aged children. Symptoms usually start 1 to 5 days after exposure and include: . Sandpaper-like rash, most often on the neck, chest, elbows, and on inner surfaces of the thighs . High fever . Sore throat . Red tongue . Tender and swollen neck glands . Sometimes nausea and vomiting Scarlet fever is usually spread from person to person by direct contact The strep bacterium is found in the nose and/or throat of persons with strep throat, and can be spread to the next person through the air with sneezing or coughing. People with scarlet fever can spread the disease to others until 24 hours after treatment. Treatment of scarlet fever is important Persons with scarlet fever can be treated with antibiotics. Treatment is important to prevent serious complications such as rheumatic fever and kidney disease. Infected children should be excluded from child care or school until 24 hours after starting treatment. Scarlet fever and strep throat can be prevented . Cover the mouth when coughing or sneezing. Wash hands after wiping or blowing nose, coughing, and sneezing. Wash hands before preparing food. See your doctor if you or your child have symptoms of scarlet fever. Maryland Department of Health Infectious Disease Epidemiology and Outbreak Response Bureau Prevention and Health Promotion Administration Web: http://health.maryland.gov February 2013 . -

Establishment of Listeria Monocytogenes in the Gastrointestinal Tract

microorganisms Review Establishment of Listeria monocytogenes in the Gastrointestinal Tract Morgan L. Davis 1, Steven C. Ricke 1 and Janet R. Donaldson 2,* 1 Center for Food Safety, Department of Food Science, University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR 72704, USA; [email protected] (M.L.D.); [email protected] (S.C.R.) 2 Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, The University of Southern Mississippi, Hattiesburg, MS 39406, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-601-266-6795 Received: 5 February 2019; Accepted: 5 March 2019; Published: 10 March 2019 Abstract: Listeria monocytogenes is a Gram positive foodborne pathogen that can colonize the gastrointestinal tract of a number of hosts, including humans. These environments contain numerous stressors such as bile, low oxygen and acidic pH, which may impact the level of colonization and persistence of this organism within the GI tract. The ability of L. monocytogenes to establish infections and colonize the gastrointestinal tract is directly related to its ability to overcome these stressors, which is mediated by the efficient expression of several stress response mechanisms during its passage. This review will focus upon how and when this occurs and how this impacts the outcome of foodborne disease. Keywords: bile; Listeria; oxygen availability; pathogenic potential; gastrointestinal tract 1. Introduction Foodborne pathogens account for nearly 6.5 to 33 million illnesses and 9000 deaths each year in the United States [1]. There are over 40 pathogens that can cause foodborne disease. The six most common foodborne pathogens are Salmonella, Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Clostridium perfringens. -

Chapter 11 – PROKARYOTES: Survey of the Bacteria & Archaea

Chapter 11 – PROKARYOTES: Survey of the Bacteria & Archaea 1. The Bacteria 2. The Archaea Important Metabolic Terms Oxygen tolerance/usage: aerobic – requires or can use oxygen (O2) anaerobic – does not require or cannot tolerate O2 Energy usage: autotroph – uses CO2 as a carbon source • photoautotroph – uses light as an energy source • chemoautotroph – gets energy from inorganic mol. heterotroph – requires an organic carbon source • chemoheterotroph – gets energy & carbon from organic molecules …more Important Terms Facultative vs Obligate: facultative – “able to, but not requiring” e.g. • facultative anaerobes – can survive w/ or w/o O2 obligate – “absolutely requires” e.g. • obligate anaerobes – cannot tolerate O2 • obligate intracellular parasite – can only survive within a host cell The 2 Prokaryotic Domains Overview of the Bacterial Domain We will look at examples from several bacterial phyla grouped largely based on rRNA (ribotyping): Gram+ bacteria • Firmicutes (low G+C), Actinobacteria (high G+C) Proteobacteria (Gram- heterotrophs mainly) Gram- nonproteobacteria (photoautotrophs) Chlamydiae (no peptidoglycan in cell walls) Spirochaetes (coiled due to axial filaments) Bacteroides (mostly anaerobic) 1. The Gram+ Bacteria Gram+ Bacteria The Gram+ bacteria are found in 2 different phyla: Firmicutes • low G+C content (usually less than 50%) • many common pathogens Actinobacteria • high G+C content (greater than 50%) • characterized by branching filaments Firmicutes Characteristics associated with this phylum: • low G+C Gram+ bacteria -

Streptococcus Pneumoniae Technical Sheet

technical sheet Streptococcus pneumoniae Classification On necropsy, a serosanguineous to purulent exudate Alpha-hemolytic, Gram-positive, encapsulated, aerobic is often found in the nasal cavities and the tympanic diplococcus bullae. The lungs can have areas of firm, dark red consolidation. Fibrinopurulent pleuritis, pericarditis, Family and peritonitis are other changes seen on necropsy of animals affected by S. pneumoniae. Histologic Streptococcaceae lesions are consistent with necropsy findings, Affected species and bronchopneumonia of varying severity and fibrinopurulent serositis are often seen. Primarily described as a pathogen of rats and guinea pigs. Mice are susceptible to infection. Agent of human Diagnosis disease and human carriers are a likely source of An S. pneumoniae infection should be suspected if animal infections. Zoonotic infection is possible. encapsulated Gram-positive diplococci are seen on a smear from a lesion. Confirmation of the diagnosis is Frequency via culture of lesions or affected tissues. S. pneumoniae Rare in modern laboratory animal colonies. Prevalence grows best on 5% blood agar and is alpha-hemolytic. in pet and wild populations unknown. The organism is then presumptively identified with an optochin test. PCR assays are also available for Transmission diagnosis. PCR-based screening for S. pneumoniae Transmission is primarily via aerosol or contact with may be conducted on respiratory samples or feces. nasal or lacrimal secretions of an infected animal. S. PCR may also be useful for confirmation of presumptive pneumoniae may be cultured from the nasopharynx and microbiologic identification or confirming the identity of tympanic bullae. bacteria observed in histologic lesions. Clinical Signs and Lesions Interference with Research Inapparent infections and carrier states are common, Animals carrying S. -

A Case of Severe Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis in an Immunocompromised Pregnant Patient

Elmer ress Case Report J Med Cases. 2015;6(6):282-284 A Case of Severe Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis in an Immunocompromised Pregnant Patient Marijo Aguileraa, c, Anne Marie Furusethb, Lauren Giacobbea, Katherine Jacobsa, Kirk Ramina Abstract festations include respiratory or neurologic involvement, acute renal failure, invasive opportunistic infections and a shock- Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA) is a tick-borne disease that like illness [2-4]. Recent delineation of the various species can often result in persistent fevers and other non-specific symptoms associated with ehrlichia infections and an increased under- including myalgias, headache, and malaise. The incidence among en- standing of the epidemiology has augmented our knowledge of demic areas has been increasing, and clinician recognition of disease these tick-borne diseases. However, a detailed understanding symptoms has aided in the correct diagnosis and treatment of patients of HGA infections in both immunocompromised and pregnant who have been exposed. While there have been few cases reported of patients is limited. We report a case of a severe HGA infection HGA disease during pregnancy, all patients have undergone a rela- presenting as an acute exacerbation of Crohn’s disease in a tively mild disease course without complications. HGA may cause pregnant immunocompromised patient. more severe disease in the elderly and immunocompromised. Herein, we report an unusual presentation and severe disease complications of HGA in a pregnant female who was concomitantly immunocompro- Case Report mised due to azathioprine treatment of her Crohn’s disease. Follow- ing successful treatment with rifampin, she subsequently delivered a A 34-year-old primigravida at 17+2 weeks’ gestation presented healthy female infant without any disease sequelae.