Johan Gunnar Andersson, Ding Wenjiang, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dates of the Discovery of the First Peking Man Fossil Teeth

The Dates of the Discovery of the First Peking Man Fossil Teeth Qian WANG,LiSUN, and Jan Ove R. EBBESTAD ABSTRACT Four teeth of Peking Man from Zhoukoudian, excavated by Otto Zdansky in 1921 and 1923 and currently housed in the Museum of Evolution at Uppsala University, are among the most treasured finds in palaeoanthropology, not only because of their scientific value but also for their important historical and cultural significance. It is generally acknowledged that the first fossil evidence of Peking Man was two teeth unearthed by Zdansky during his excavations at Zhoukoudian in 1921 and 1923. However, the exact dates and details of their collection and identification have been documented inconsistently in the literature. We reexamine this matter and find that, due to incompleteness and ambiguity of early documentation of the discovery of the first Peking Man teeth, the facts surrounding their collection and identification remain uncertain. Had Zdansky documented and revealed his findings on the earliest occasion, the early history of Zhoukoudian and discoveries of first Peking Man fossils would have been more precisely known and the development of the field of palaeoanthropology in early twentieth century China would have been different. KEYWORDS: Peking Man, Zhoukoudian, tooth, Uppsala University. INTRODUCTION FOUR FOSSIL TEETH IDENTIFIED AS COMING FROM PEKING MAN were excavated by palaeontologist Otto Zdansky in 1921 and 1923 from Zhoukoudian deposits. They have been housed in the Museum of Evolution at Uppsala University in Sweden ever since. These four teeth are among the most treasured finds in palaeoanthropology, not only because of their scientific value but also for their historical and cultural significance. -

Bedrock of China Xu Xing Applauds a Study Tracing the Links Between Chinese Nationalism and Geology

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS GEOLOGY Bedrock of China Xu Xing applauds a study tracing the links between Chinese nationalism and geology. hinese science has long been tightly igneous formations of Unearthing the Chinese geologists persisted in fostering entangled with nationalism. An illu- Belgium for his thesis Nation: Modern an independent discipline, even in 1927–37, minating case study is the develop at the University of Geology and when frequent conflicts flared between the Cment of geology during the Republican era Louvain. These pio- Nationalism in government in Nanjing and local warlords, Republican China (1911–49). This followed an unusual pattern, neers, Shen says, saw GRACE YEN SHEN and within the ruling party. Weng and oth- striking a balance between the interests of sci- fieldwork as helping University of Chicago ers recognized that their field could help to ence, the nationalist movement, the state and China to “understand Press: 2014. satisfy practical needs of the state such as scientists in difficult, unstable circumstances. its own territory”: sci- the search for fossil fuels, and could build Science historian Grace Yen Shen chronicles ence thus became a means of nation-building. national pride. A platform came in 1936 the field’s evolution in Unearthing the Nation. Yet for years, Chinese geology remained with the GSC’s Chinese-language journal Shen begins with an account of foreign internationally collaborative in terms of Dizhi Lunping (Geological Review). And exploration in Chinese territory from the practitioners, fieldwork, institutions and the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937–45 mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth publications. In the 1920s, China was pri- was a watershed: the drive to find natural centuries, such as US geologist Raphael marily agrarian and lacked the financial and resources for the war effort led to achieve- Pumpelly’s investigations of the coalfields intellectual resources to cultivate science. -

Andersson, Johan Gunnar, 45–67

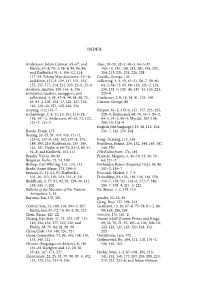

INDEX Andersson, Johan Gunnar, 45–67; and class, 18–20, 32–7, 40–3, 64–5, 87, Hedin, 67–8, 70–4, 78–9, 90, 95, 99; 105–10, 140, 158, 181, 183, 193, 202, and Karlbeck,101–3, 106–12, 114, 204, 213, 221, 224, 226, 228 117–19; Peking Man discovery, 121–8; Coedès, George, 142 and Sirén, 133–6, 139, 141, 151, 153, collecting, 1–4, 43, 45–51, 56–7, 59–60, 155, 157, 177, 214, 221, 223, 22–6, 22–9 64–5, 68–72, 85, 89–119, 121–2, 124, Andreen, Andrea, 158, 163–4, 196 130, 132–6, 138–44, 147–53, 165, 221, antiquities (dealers, smugglers, and 225–8 collectors), 3, 43, 47–9, 59, 64, 69, 72, Confucius, 2, 8, 18, 39, 41, 129, 149 85, 91–2, 101, 104–17, 121, 127, 132, Curzon, George, 88 136, 139–43, 151, 165, 224, 226 Anyang, 112, 115–7 Empire, 63–5, 115–6, 151, 177, 223, 225, archaeology, 2, 4, 11, 15, 101, 115–18, 228–9; Hedin and, 68, 74, 76–7, 80–2, 138, 141–2; Andersson, 47–65, 72, 122, 84–5, 91–2, 98–9; Myrdal, 187, 198, 124–7, 134–5 200–10, 218–9 English (the language), 19, 38, 112, 124, Baude, Frank, 175 136–7, 145, 159, 204 Beijing, 36, 45, 51, 101, 116, 121–2, 125–6, 157–9, 161, 163, 167–8, 175, Feng, Yuxiang, 113, 136 189, 195, 216; Karlbeck in, 135–140, Fenollosa, Ernest, 130, 132, 144, 145, 147, 143, 151; Hedin in 69–76, 81–2, 85, 91, 149, 150 94–8; and Karlbeck, 103, 113 FIB/Kulturfront, 176, 185 Bendix, Victor, 90, 95 Fiskesjö, Magnus, 3, 46–50, 53, 56, 59, Bergman, Folke, 73, 74, 109 64, 121–2 Bishop, Carl Whiting, 115, 134, 142 Forbidden Palace (Imperial City), 36, 96, Brady, Anne-Marie, 173, 194–5 101–2, 136–7 bronzes,11, 15, 61, 95; -

Chapter 1 Chinese Archaeology: Past, Present

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-64310-8 - Cambridge World Archaeology: The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age Li Liu and Xingcan Chen Excerpt More information CHAPTER 1 CHINESE ARCHAEOLOGY: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE The archaeological materials recovered from the Anyang excavations . in the period between 1928 and 1937 ...havelaidanewfoundation for the study of ancient China. (Li, C. 1977:ix) When inscribed oracle bones and enormous material remains were found through scientific excavation in Anyang in 1928, the historicity of the Shang dynasty was confirmed beyond dispute for the first time (Li, C. 1977: ix–xi). This excavation thus marked the beginning of a modern Chinese archaeology endowed with great potential to reveal much of China’s ancient history. Half a century later, Chinese archaeology had made many unprecedented discoveries that surprised the world, leading Glyn Daniel to believe that “a new awareness of the importance of China will be a key development in archaeology in the decades ahead” (Daniel 1981: 211). This enthusiasm was soon shared by the Chinese archaeologists when Su Bingqi announced that “the Golden Age of Chinese archaeology is arriving” (Su, B. 1994: 139–40). In recent decades, archaeology has continuously prospered, becoming one of the most rapidly developing fields of social science in China. As suggested by Bruce Trigger (Trigger 1984), three basic types of archae- ology are practiced worldwide: nationalist, colonialist, and imperialist. China’s archaeology clearly falls into the first category. Archaeology in China is defined as a discipline within the study of history that deals with material remains of the past and aims to reveal the laws of historical evolution, based on histor- ical materialism (Xia and Wang 1986: 1–3). -

Paleoanthropology and Anthropology in the Chinese Frontier, 1920-1950

Constructing the Chinese: Paleoanthropology and Anthropology in the Chinese Frontier, 1920-1950 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Yen, Hsiao-pei. 2012. Constructing the Chinese: Paleoanthropology and Anthropology in the Chinese Frontier, 1920-1950. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10086027 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Copyright ©2012 by Hsiao-pei Yen All rights reserved To My Parents Advisor: Professor Henrietta Harrison Hsiao-pei Yen Constructing the Chinese: Paleoanthropology and Anthropology in the Chinese Frontier, 1920-1950 ABSTRACT Today’s Chinese ethno-nationalism exploits nativist ancestral claims back to antiquity to legitimize its geo-political occupation of the entire territory of modern China, which includes areas where many non-Han people live. It also insists on the inseparability of the non-Han nationalities as an integrated part of Zhonghua minzu. This dissertation traces the origin of this nationalism to the two major waves of scientific investigation in the fields of paleoanthropology and anthropology in the Chinese frontier during the first half of the twentieth century. Prevailing theories and discoveries in the two scientific disciplines inspired the ways in which the Chinese intellectuals constructed their national identity. The first wave concerns the international quest for human ancestors in North China and the northwestern frontier in the 1920s and 1930s. -

From Terra Incognita to MANIAS Firstonline26may2016 GREEN

King’s Research Portal Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Manias, C. P. (2016). From Terra incognita to Garden of Eden: Unveiling the prehistoric life of China and Central Asia, 1890-1930 . In R. Bickers, & I. Jackson (Eds.), Treaty Ports in Modern China : Law, Land and Power (pp. 201-219). Routledge. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Archaeology and Paleontology Kǎogǔxué Hé Gǔshēngwùxué 考古学和古生物学

◀ Aquaculture Comprehensive index starts in volume 5, page 2667. Archaeology and Paleontology Kǎogǔxué hé gǔshēngwùxué 考古学和古生物学 Modern field paleontology and archaeology Dynasty, c. 100 ce) mentions the find of dragon bones ( were introduced to China in the early twen- 龙骨, fossils) in 133 bce during work on a canal. Several tieth century. Fossil remains have provided sources during the next millennium refer to fossils as an- new insights into the evolution of life, pa- cient animals and plants, and some books have passages remarkably similar to those in modern paleontology. The leoanthropological remains on the evolution Yun Lin Shi Pu (云林石谱, Stone Catalogue of Cloudy of mankind, and archaeological excavations Forest, 1033 ce), for instance, contains detailed descrip- on the development of human cultures. The tions of fossil fishes. Fossils have been collected since an- last twenty years have seen a marked improve- cient times and used in traditional Chinese medicine for ment in research quality, an explosion of new their supposed magical powers and ability to cure disease. data, and several scientific breakthroughs. Still, in the 1950s, paleontologists made major discoveries by asking the local population where they collected their dragon bones. The earliest Chinese experiments in what resembles rchaeology (the study of material remains of modern archaeology were made during the Song dynasty past human life), and paleontology (the study (960– 1279) when ancient inscriptions found on stones of life of the geological past and the evolution and bronzes were studied and catalogued. This tradi- of life) in China share a common past. The first generation tion, although interrupted at the beginning of the Yuan of Western-educated Chinese scholars worked together in dynasty (1279– 1368), continued well into the late Qing the field as geologists, paleontologists, and archaeologists dynasty (1644– 1912). -

HISTORIA NATURAL Tercera Serie Volumen 11 (1) 2021/47-63

ISSN 0326-1778 (Impresa) ISSN 1853-6581 (En Línea) HISTORIA NATURAL Tercera Serie Volumen 11 (1) 2021/47-63 Número dedicado a la Historia de las Ciencias Naturales Dragon’S eggs from THE “YELLOW Earth”: THE discovery OF THE fossil ostriches OF CHINA Huevos de dragón en la “Tierra amarilla”: El descubrimiento de avestruces fósiles en China. Eric Buffetaut CNRS (UMR 8538), Laboratoire de Géologie de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure, PSL Research University, 24 rue Lhomond, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. [email protected] Palaeontological Research and Education Centre, Maha Sarakham University, Maha Sarakham 44150, Thailand HISTORIA NATURAL Tercera Serie Volumen 11 (1) 2020/37-46 47 BUFFETAUT E. Abstract. Fossil ostrich eggs, mainly from the Pleistocene loess (the “yellow earth”, huáng tǔ in Chinese), have been known to the Chinese for a long time. They were sometimes interpreted as dragon’s eggs and were valued as curios. Palaeontologists first heard about them at the end of the 19th century, when a missionary in northern China obtained such an egg from a local farmer and sold it to Harvard University, where it was described by Charles Eastman in 1898, who referred it to Struthiolithus chersonensis Brandt, 1872, a taxon based on a fossil egg from Ukraine. More eggs obtained by missionaries subsequently found their way to various collections in the United States, Canada, Britain and Italy. The first western scientists to collect fossil ostrich eggs in situ in China, in the second decade of the 20th century, were the French Jesuit and naturalist Emile Licent and the Swedish geologist and archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson. -

Saluting the Yellow Emperor Sinica Leidensia

Saluting the Yellow Emperor Sinica Leidensia Edited by Barend J. ter Haar Maghiel van Crevel In co-operation with P.K. Bol, D.R. Knechtges, E.S. Rawski, W.L. Idema, H.T. Zurndorfer VOLUME 104 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/sinl Saluting the Yellow Emperor A Case of Swedish Sinography By Perry Johansson LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 The lion share of this book originates fromSinofilerna published in Swedish by Carlsson 2008. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Johansson, Perry. Saluting the yellow emperor : a case of Swedish sinography / Perry Johansson. p. cm. — (Sinica leidensia, ISSN 0169-9563 ; v. 104) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-22097-3 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. China—Civilization— To 221 B.C.—Historiography. 2. Sinologists—Sweden—History—20th century. 3. Historiography—Sweden—History—20th century. 4. Excavations (Archaeology)— China. 5. Karlgren, Bernhard, 1889–1978. 6. Andersson, Johan Gunnar, 1874–1960. 7. Hedin, Sven Anders, 1865–1952. 8. Myrdal, Jan. I. Title. DS741.25.J65 2012 932.0072’022485—dc23 2011037324 ISSN 0169-9563 ISBN 978 90 04 22097 3 (hardback) ISBN 978 90 04 22639 5 (e-book) Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

Zhoukoudian, Archaeology Of

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341115053 Archaeology Zhoukoudian Chapter · January 2014 CITATIONS READS 0 76 2 authors: Xiaoling Zhang Chen Shen Chinese Academy of Sciences Royal Ontario Museum 20 PUBLICATIONS 281 CITATIONS 118 PUBLICATIONS 645 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Object of the Past: Art and Archaeology of Early China View project The Shandong Project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Chen Shen on 03 May 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Z 7958 Zhoukoudian, Archaeology of Most recently, Zhan has organized the ICOMOS Asia-Pacific Group meetings in Zhoukoudian, Archaeology of China, worked with the international and national post-disaster heritage rescue and protection mea- Xiaoling Zhang1 and Chen Shen2 sures in the wake of Wenchuan earthquake in 1Department of Palaeoanthropology, Institute of 2008, and presented at various symposia on the Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, protection and management of cultural land- Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China scapes, industrial heritage, and the Grand Canal 2Department of World Cultures, Royal Ontario of China. Museum, Toronto, ON, Canada He is engaged in the conservation and moni- toring of heritage sites in China and serves as chair of the International Symposium on the Introduction Concepts and Practices of Conservation and Restoration of Historic Buildings in East Asia. Zhoukoudian is located in the Fangshan District, He participated in the revision of the Principles 55 km southwest of downtown Beijing. A hill for the Conservation of Heritage Sites in China called Longgushan “Dragon Bone Hill” was and organized the translation into Chinese of known by local farmers in the early twentieth History of Architectural Conservation written century for Ordovician limestone quarrying. -

Oscar Montelius and Chinese Archaeology

Chen, X and Fiskesjö, M 2014 Oscar Montelius and Chinese Archaeology. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 24: 10, pp. 1–10, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/bha.2410 PAPER Oscar Montelius and Chinese Archaeology Chen Xingcan* and Magnus Fiskesjö† This paper demonstrates that Oscar Montelius (1843–1921), the world-famous Swedish archaeol- ogist, had a key role in the development of modern scientific Chinese archaeology and the discov- ery of China’s prehistory. We know that one of his major works, Die Methode, the first volume of his Älteren kulturperioden im Orient und in Europa, translated into Chinese in the 1930s, had con- siderable influence on generations of Chinese archaeologists and art historians. What has previ- ously remained unknown, is that Montelius personally promoted the research undertaken in China by Johan Gunnar Andersson (1874–1960), whose discoveries of Neolithic cultures in the 1920s constituted the breakthrough and starting point for the development of prehistoric archaeology in China. In this paper, we reproduce, translate and discuss a long forgotten memorandum written by Montelius in 1920 in support of Andersson’s research. In this Montelius indicated his belief in the potential of prehistoric Chinese archaeology as well as his predictions regarding the discov- eries about to be made. It is therefore an important document for the study of the history of Chinese archaeology as a whole. Introduction: Montelius in China project of Die Methode’ (Montelius 1937 [‘Translator’s We are all familiar with the work of Oscar Montelius Foreword’]: 1). (1843–1921), which occupies a central position in the Die Methode appears to have first caught the atten- history of world archaeology. -

Otto Zdansky - Mannen Som Gjorde De Första Fynden Av Pekingmänniskan Avclasthor

RÅTTANS ÅR o Arsbok om Kina Redaktion: Anders Lennartsson (redaktör) Erik Berg!öL Harriet Johansson, Per-Olof Lansing, Per-Olow Leijon, Torbjörn Loden, Hans Seyler. j I r .'"1 rna --r- e r r Svensk-kinesiska vänskapsförbundet I denna serie 1979 - Getens år 1985 - Oxens år 1980 - Apans år 1986 - Tigerns år 198 I - Tuppens år 1987 - Kaninens år 1982 - H undens år 1988 - Drakens år 1983 - Grisens år 1989 - Ormens år 1984 - Råttans år 1990 - Hästens år Redaktionell anmärkning Kinesiska namn transkriberas i huvudsak enli gt pinyin systemet, dvs fonetiskt med våra latinska bokstäver. Undantag är t ex "Peking" och " Kanton"', icke han kinesiska namn samt några kinesiska namn där artikelförfattaren förordat annan transkribering. Omslaget: Originalmålning för årsboken av Hu Shuang'an Konstnären Hu Shuang'an är 67 år och kommer från Xiangyang i provinsen Hubei. Han studerade redan på 30-talet djur- och landskapsmåleri . Han är medlem av konstnärsförbundet och sekreterare i Äldre kinesiska kalligrafers forskningssällskap. Bilderna från Svensk-kinesiska vänskapsförbundets bildarkiv om ej annat anges. ISBN 91-85538-11-6 © Svensk-kinesiska vänskapsförbundet Stockholm 1984. Ordfront tryckeri & förlag AB Otto Zdansky - mannen som gjorde de första fynden av pekingmänniskan AvClasThor Det går att föreställa sig ögonblicket: alma presentant i landet, faller in i den svenska nackan i portierlogen på Grand Hötel de Pekin hyllningskören börjar vetenskapsmännen visar den 22 oktober 1926. Strax efter lunchvi skruva på sig. De har inte tänkt sig att sitta en lans slut rör sig ett följe genom hotelJvestibu hel eftermiddag och bara höra svenskar hylla len. Portiern bugar sig, vinkar åt dörrpojkarna svenskar.