Part II. Writings ABOUT Andersson and His Works: an Eclectic List 1899

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zhou Zuoren's Critique of Violence in Modern China

World Languages and Cultures Publications World Languages and Cultures 2014 The aS cred and the Cannibalistic: Zhou Zuoren’s Critique of Violence in Modern China Tonglu Li Iowa State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/language_pubs Part of the Chinese Studies Commons The ompc lete bibliographic information for this item can be found at http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ language_pubs/102. For information on how to cite this item, please visit http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/ howtocite.html. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Cultures at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in World Languages and Cultures Publications by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS cred and the Cannibalistic: Zhou Zuoren’s Critique of Violence in Modern China Abstract This article explores the ways in which Zhou Zuoren critiqued violence in modern China as a belief-‐‑driven phenomenon. Differing from Lu Xun and other mainstream intellectuals, Zhou consistently denied the legitimacy of violence as a force for modernizing China. Relying on extensive readings in anthropology, intellectual history, and religious studies, he investigated the fundamental “nexus” between violence and the religious, political, and ideological beliefs. In the Enlightenment’s effort to achieve modernity, cannibalistic Confucianism was to be cleansed from the corpus of Chinese culture as the “barbaric” cultural Other, but Zhou was convinced that such barbaric cannibalism was inherited by the Enlightenment thinkers, and thus made the Enlightenment impossible. -

Forgotten Crocodile from the Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, New

posed that the narial cavities of Para- Wima1l- saurolophuswere vocal resonating chambers' Goniopholiskirtlandicus Apparently included with this material shippedto Wiman was a partial skull that lromthe Wiman describedas a new speciesof croc- forgottencrocodile odile, Goniopholis kirtlandicus. Wiman publisheda descriptionof G. kirtlandicusin Basin, 1932in the Bulletin of the GeologicalInstitute KirtlandFormation, San Juan of IJppsala. Notice of this specieshas not appearedin any Americanpublication. Klilin NewMexico (1955)presented a descriptionand illustration of the speciesin French, but essentially repeatedWiman (1932). byDonald L. Wolberg, Vertebrate Paleontologist, NewMexico Bureau of lVlinesand Mineral Resources, Socorro, NIM Localityinformation for Crocodilian bone, armor, and teeth are Goni o p holi s kir t landicus common in Late Cretaceous and Early Ter- The skeletalmaterial referred to Gonio- tiary deposits of the San Juan Basin and pholis kirtlandicus includesmost of the right elsewhere.In the Fruitland and Kirtland For- side of a skull, a squamosalfragment, and a mations of the San Juan Basin, Late Creta- portion of dorsal plate. The referral of the ceous crocodiles were important carnivores of dorsalplate probably represents an interpreta- the reconstructed stream and stream-bank tion of the proximity of the material when community (Wolberg, 1980). In the Kirtland found. Figs. I and 2, taken from Wiman Formation, a mesosuchian crocodile, Gonio- (1932),illustrate this material. pholis kirtlandicus, discovered by Charles H. Wiman(1932, p. 181)recorded the follow- Sternbergin the early 1920'sand not described ing locality data, provided by Sternberg: until 1932 by Carl Wiman, has been all but of Crocodile.Kirtland shalesa 100feet ignored since its description and referral. "Skull below the Ojo Alamo Sandstonein the blue Specimensreferred to other crocodilian genera cley. -

Brains and Intelligence

BRAINS AND INTELLIGENCE The EQ or Encephalization Quotient is a simple way of measuring an animal's intelligence. EQ is the ratio of the brain weight of the animal to the brain weight of a "typical" animal of the same body weight. Assuming that smarter animals have larger brains to body ratios than less intelligent ones, this helps determine the relative intelligence of extinct animals. In general, warm-blooded animals (like mammals) have a higher EQ than cold-blooded ones (like reptiles and fish). Birds and mammals have brains that are about 10 times bigger than those of bony fish, amphibians, and reptiles of the same body size. The Least Intelligent Dinosaurs: The primitive dinosaurs belonging to the group sauropodomorpha (which included Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, and others) were among the least intelligent of the dinosaurs, with an EQ of about 0.05 (Hopson, 1980). Smartest Dinosaurs: The Troodontids (like Troödon) were probably the smartest dinosaurs, followed by the dromaeosaurid dinosaurs (the "raptors," which included Dromeosaurus, Velociraptor, Deinonychus, and others) had the highest EQ among the dinosaurs, about 5.8 (Hopson, 1980). The Encephalization Quotient was developed by the psychologist Harry J. Jerison in the 1970's. J. A. Hopson (a paleontologist from the University of Chicago) did further development of the EQ concept using brain casts of many dinosaurs. Hopson found that theropods (especially Troodontids) had higher EQ's than plant-eating dinosaurs. The lowest EQ's belonged to sauropods, ankylosaurs, and stegosaurids. A SECOND BRAIN? It used to be thought that the large sauropods (like Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus) and the ornithischian Stegosaurus had a second brain. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Hobsbawm 1990, 66. 2. Diamond 1998, 322–33. 3. Fairbank 1992, 44–45. 4. Fei Xiaotong 1989, 1–2. 5. Diamond 1998, 323, original emphasis. 6. Crossley 1999; Di Cosmo 1998; Purdue 2005a; Lavely and Wong 1998, 717. 7. Richards 2003, 112–47; Lattimore 1937; Pan Chia-lin and Taeuber 1952. 8. My usage of the term “geo-body” follows Thongchai 1994. 9. B. Anderson 1991, 86. 10. Purdue 2001, 304. 11. Dreyer 2006, 279–80; Fei Xiaotong 1981, 23–25. 12. Jiang Ping 1994, 16. 13. Morris-Suzuki 1998, 4; Duara 2003; Handler 1988, 6–9. 14. Duara 1995; Duara 2003. 15. Turner 1962, 3. 16. Adelman and Aron 1999, 816. 17. M. Anderson 1996, 4, Anderson’s italics. 18. Fitzgerald 1996a: 136. 19. Ibid., 107. 20. Tsu Jing 2005. 21. R. Wong 2006, 95. 22. Chatterjee (1986) was the first to theorize colonial nationalism as a “derivative discourse” of Western Orientalism. 23. Gladney 1994, 92–95; Harrell 1995a; Schein 2000. 24. Fei Xiaotong 1989, 1. 25. Cohen 1991, 114–25; Schwarcz 1986; Tu Wei-ming 1994. 26. Harrison 2000, 240–43, 83–85; Harrison 2001. 27. Harrison 2000, 83–85; Cohen 1991, 126. 186 • Notes 28. Duara 2003, 9–40. 29. See, for example, Lattimore 1940 and 1962; Forbes 1986; Goldstein 1989; Benson 1990; Lipman 1998; Millward 1998; Purdue 2005a; Mitter 2000; Atwood 2002; Tighe 2005; Reardon-Anderson 2005; Giersch 2006; Crossley, Siu, and Sutton 2006; Gladney 1991, 1994, and 1996; Harrell 1995a and 2001; Brown 1996 and 2004; Cheung Siu-woo 1995 and 2003; Schein 2000; Kulp 2000; Bulag 2002 and 2006; Rossabi 2004. -

The Dates of the Discovery of the First Peking Man Fossil Teeth

The Dates of the Discovery of the First Peking Man Fossil Teeth Qian WANG,LiSUN, and Jan Ove R. EBBESTAD ABSTRACT Four teeth of Peking Man from Zhoukoudian, excavated by Otto Zdansky in 1921 and 1923 and currently housed in the Museum of Evolution at Uppsala University, are among the most treasured finds in palaeoanthropology, not only because of their scientific value but also for their important historical and cultural significance. It is generally acknowledged that the first fossil evidence of Peking Man was two teeth unearthed by Zdansky during his excavations at Zhoukoudian in 1921 and 1923. However, the exact dates and details of their collection and identification have been documented inconsistently in the literature. We reexamine this matter and find that, due to incompleteness and ambiguity of early documentation of the discovery of the first Peking Man teeth, the facts surrounding their collection and identification remain uncertain. Had Zdansky documented and revealed his findings on the earliest occasion, the early history of Zhoukoudian and discoveries of first Peking Man fossils would have been more precisely known and the development of the field of palaeoanthropology in early twentieth century China would have been different. KEYWORDS: Peking Man, Zhoukoudian, tooth, Uppsala University. INTRODUCTION FOUR FOSSIL TEETH IDENTIFIED AS COMING FROM PEKING MAN were excavated by palaeontologist Otto Zdansky in 1921 and 1923 from Zhoukoudian deposits. They have been housed in the Museum of Evolution at Uppsala University in Sweden ever since. These four teeth are among the most treasured finds in palaeoanthropology, not only because of their scientific value but also for their historical and cultural significance. -

Yanchang Oilfield

Chapter 3 China’s First On-Land Oilfield: Yanchang Oilfield 1 Yanchang Oilfield Established, 1905 Yanchang Oilfield is situated in the vast area east of Yan’an in northern Shaanxi Province and west of the Yellow River. Geologically, it belongs to the Ordos Basin, which covers the provinces of Shaanxi, Gansu, Ningxia, Shanxi, and Inner Mongolia. Its topography, with abundant gullies and ravines, is typical of the Loess Plateau. The existence of oil in northern Shaanxi has been well- documented in Chinese historical records since early times. In 1905, the Qing dynasty Governor of Shaanxi Province, Cao Hongxun 曹洪勋, wrote a memorial to the throne, requesting permission to establish the Yanchang Oilfield. Although the Qing court granted his request, it did not give him any funding. He boldly used 81,000 taels (= 2,331.25 kg) of the local government’s silver originally intended for wasteland reclamation to build the oilfield. He appointed Expectant District Magistrate Hong Yin 洪寅 to oversee the operation. After two years of preparation, they hired a Japanese technician, Satō Hisarō 佐藤弥朗, who started drilling at Yan-1 Well, in Qili Village 七里村, on June 5, 1907, using a percussion rig brought from Niigata, Japan. Drilling was completed at 81 m on September 10, and the well had an initial daily out- put of 1 to 1.5 tons, which it maintained for ten years. The crude oil from Yan-1 was processed in small copper pots and produced 12.5 kg of lamp oil per day. It was sent for analysis in Xi’an, and it was found that when burnt, it produced a small amount of white smoke. -

Jade Huang and Chinese Culture Identity: Focus on the Myth of “Huang of Xiahoushi”

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, June 2016, Vol. 6, No. 6, 603-618 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2016.06.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Jade Huang and Chinese Culture Identity: Focus on the Myth of “Huang of Xiahoushi” TANG Qi-cui, WU Yu-wei Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China This paper focus on the myth of “Huang of Xiahoushi” (夏后氏之璜), focusing on the distribution of Jade Huang (玉璜) since the early neolithic and its process of pluralistic integration. The paper explores the story of ethnic group, cultural identification and the significance of Jade Huang in the discourse construction of etiquette civilization behind the mythic narrative based on multi-evidence method and the local meaning of literature in ancient Chinese context. Keywords: Jade Huang, Huang of Xiahoushi, unified diversity, Chinese identity, etiquette civilization, multi-evidence method Introduction Modern archeological relics including potteries, jades and bronzes bring back the lost history; the process of how Chinese unified diversity took shape in general and the great tradition of jade culture in eight thousand in particular. The handed-down documents echo each other at a distance provide solid evidences for the origin of civilization of rite and music and the core values based on jade belief. Jade Huang is an important one of it. It is illuminated by numerous records about Jade Huang in ancient literature, as well as a large number of archaeology findings past 7,000 years. The paper seeks to focus on the following questions: what is the function of Jade Huang in historic and prehistoric period? Moreover, what is the function of “Huang of Xiahoushi”, which belonged to emperor and symbolized special power in historic documents and myths and legends in ancient china? Jade Huang: Etiquette and Literature Jade Huang (Yu Huang, Semi-circular/annular Jade Pendant) is a type of jade artifact which is seemed to be remotely related to etiquette and literature. -

The Early Paleolithic of China1) HUANG Weiwen2)

第 四 紀 研 究 (The Quaternary Research) 28 (4) p. 237-242 Nov. 1989 The Early Paleolithic of China1) HUANG Weiwen2) spread widely and existed for a long time. The Introduction deposits contained very rich fossils of mammal. 1. Geographic Distribution and the Types of The fauna exisiting in the stage from the early Deposits to the middle Pleistocene can be at least divided Before the 1940's, only one locality of the into three groups, which have their own Early Paleolithic period was discovered in characteristics and sequence: Nihewan fauna of China. That is Zhoukoudian near Beijing early Pleistocene, Gongwangling (Lantian Man) City (the site of Peking Man). Since the 1950's fauna of the latest stage of early Pleistocene many new localities have been found, of which or the earliest stage of middle Pleistocene and no less than fifteen are relatively important. Zhoukoudian (Peking Man) fauna of the middle These localities spread in North, South and Pleistocene. In the recent years, some scholars Northeast China covering a range from 23°35' to have suggested that locations of Dali and 40°15'N and from 101°58' to 124°8'E which Dingcun which originally recognized as be- includes two climate zones, namely, the sub- longing to the early stage of late Pleistocene tropical zone and warm temperate zone in the should place in the middle Pleistocene, as the eastern part of today's Asia (Fig. 1). latest stage of this epoch (LIU and DING,1984). The localities include three types of deposit: There also existed fluviatile and fluviol- 1) Fluviatile deposit: acustrine deposits of Pleistocene in South Xihoudu (Shanxi), Kehe (Shanxi), Lantian China. -

Bedrock of China Xu Xing Applauds a Study Tracing the Links Between Chinese Nationalism and Geology

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS GEOLOGY Bedrock of China Xu Xing applauds a study tracing the links between Chinese nationalism and geology. hinese science has long been tightly igneous formations of Unearthing the Chinese geologists persisted in fostering entangled with nationalism. An illu- Belgium for his thesis Nation: Modern an independent discipline, even in 1927–37, minating case study is the develop at the University of Geology and when frequent conflicts flared between the Cment of geology during the Republican era Louvain. These pio- Nationalism in government in Nanjing and local warlords, Republican China (1911–49). This followed an unusual pattern, neers, Shen says, saw GRACE YEN SHEN and within the ruling party. Weng and oth- striking a balance between the interests of sci- fieldwork as helping University of Chicago ers recognized that their field could help to ence, the nationalist movement, the state and China to “understand Press: 2014. satisfy practical needs of the state such as scientists in difficult, unstable circumstances. its own territory”: sci- the search for fossil fuels, and could build Science historian Grace Yen Shen chronicles ence thus became a means of nation-building. national pride. A platform came in 1936 the field’s evolution in Unearthing the Nation. Yet for years, Chinese geology remained with the GSC’s Chinese-language journal Shen begins with an account of foreign internationally collaborative in terms of Dizhi Lunping (Geological Review). And exploration in Chinese territory from the practitioners, fieldwork, institutions and the Second Sino-Japanese War of 1937–45 mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth publications. In the 1920s, China was pri- was a watershed: the drive to find natural centuries, such as US geologist Raphael marily agrarian and lacked the financial and resources for the war effort led to achieve- Pumpelly’s investigations of the coalfields intellectual resources to cultivate science. -

Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia

World Heritage papers41 HEADWORLD HERITAGES 4 Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia VOLUME I In support of UNESCO’s 70th Anniversary Celebrations United Nations [ Cultural Organization Human Origin Sites and the World Heritage Convention in Eurasia Nuria Sanz, Editor General Coordinator of HEADS Programme on Human Evolution HEADS 4 VOLUME I Published in 2015 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and the UNESCO Office in Mexico, Presidente Masaryk 526, Polanco, Miguel Hidalgo, 11550 Ciudad de Mexico, D.F., Mexico. © UNESCO 2015 ISBN 978-92-3-100107-9 This publication is available in Open Access under the Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repository (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Cover Photos: Top: Hohle Fels excavation. © Harry Vetter bottom (from left to right): Petroglyphs from Sikachi-Alyan rock art site. -

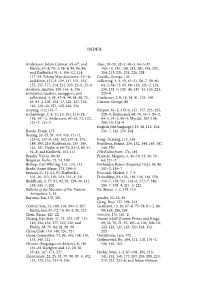

Andersson, Johan Gunnar, 45–67

INDEX Andersson, Johan Gunnar, 45–67; and class, 18–20, 32–7, 40–3, 64–5, 87, Hedin, 67–8, 70–4, 78–9, 90, 95, 99; 105–10, 140, 158, 181, 183, 193, 202, and Karlbeck,101–3, 106–12, 114, 204, 213, 221, 224, 226, 228 117–19; Peking Man discovery, 121–8; Coedès, George, 142 and Sirén, 133–6, 139, 141, 151, 153, collecting, 1–4, 43, 45–51, 56–7, 59–60, 155, 157, 177, 214, 221, 223, 22–6, 22–9 64–5, 68–72, 85, 89–119, 121–2, 124, Andreen, Andrea, 158, 163–4, 196 130, 132–6, 138–44, 147–53, 165, 221, antiquities (dealers, smugglers, and 225–8 collectors), 3, 43, 47–9, 59, 64, 69, 72, Confucius, 2, 8, 18, 39, 41, 129, 149 85, 91–2, 101, 104–17, 121, 127, 132, Curzon, George, 88 136, 139–43, 151, 165, 224, 226 Anyang, 112, 115–7 Empire, 63–5, 115–6, 151, 177, 223, 225, archaeology, 2, 4, 11, 15, 101, 115–18, 228–9; Hedin and, 68, 74, 76–7, 80–2, 138, 141–2; Andersson, 47–65, 72, 122, 84–5, 91–2, 98–9; Myrdal, 187, 198, 124–7, 134–5 200–10, 218–9 English (the language), 19, 38, 112, 124, Baude, Frank, 175 136–7, 145, 159, 204 Beijing, 36, 45, 51, 101, 116, 121–2, 125–6, 157–9, 161, 163, 167–8, 175, Feng, Yuxiang, 113, 136 189, 195, 216; Karlbeck in, 135–140, Fenollosa, Ernest, 130, 132, 144, 145, 147, 143, 151; Hedin in 69–76, 81–2, 85, 91, 149, 150 94–8; and Karlbeck, 103, 113 FIB/Kulturfront, 176, 185 Bendix, Victor, 90, 95 Fiskesjö, Magnus, 3, 46–50, 53, 56, 59, Bergman, Folke, 73, 74, 109 64, 121–2 Bishop, Carl Whiting, 115, 134, 142 Forbidden Palace (Imperial City), 36, 96, Brady, Anne-Marie, 173, 194–5 101–2, 136–7 bronzes,11, 15, 61, 95; -

A Giant Ostrich from the Lower Pleistocene Nihewan Formation of North China, with a Review of the Fossil Ostriches of China

diversity Review A Giant Ostrich from the Lower Pleistocene Nihewan Formation of North China, with a Review of the Fossil Ostriches of China Eric Buffetaut 1,2,* and Delphine Angst 3 1 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique—CNRS (UMR 8538), Laboratoire de Géologie de l’Ecole Normale Supérieure, PSL Research University, 24 rue Lhomond, CEDEX 05, 75231 Paris, France 2 Palaeontological Research and Education Centre, Maha Sarakham University, Maha Sarakham 44150, Thailand 3 School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Life Sciences Building, 24 Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TQ, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: A large incomplete ostrich femur from the Lower Pleistocene of North China, kept at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (Paris), is described. It was found by Father Emile Licent in 1925 in the Nihewan Formation (dated at about 1.8 Ma) of Hebei Province. On the basis of the minimum circumference of the shaft, a mass of 300 kg, twice that of a modern ostrich, was obtained. The bone is remarkably robust, more so than the femur of the more recent, Late Pleistocene, Struthio anderssoni from China, and resembles in that regard Pachystruthio Kretzoi, 1954, a genus known from the Lower Pleistocene of Hungary, Georgia and the Crimea, to which the Nihewan specimen is referred, as Pachystruthio indet. This find testifies to the wide geographical distribution Citation: Buffetaut, E.; Angst, D. A of very massive ostriches in the Early Pleistocene of Eurasia. The giant ostrich from Nihewan was Giant Ostrich from the Lower contemporaneous with the early hominins who inhabited that region in the Early Pleistocene.