Perceived Firm Transparency: Scale and Model Development Jennifer Dapko University of South Florida, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patrol Guide § 212-72

EXHIBIT K AOR307 An Investigation of NYPD’s Compliance with Rules Governing Investigations of Political Activity New York City Department of Investigation Office of the Inspector General for the NYPD (OIG-NYPD) Mark G. Peters Commissioner Philip K. Eure Inspector General for the NYPD August 23, 2016 AOR308 AN INVESTIGATION OF NYPD’S COMPLIANCE WITH RULES GOVERNING AUGUST 2016 INVESTIGATIONS OF POLITICAL ACTIVITY Table of Contents Overview ............................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 11 I. NYPD Investigations of Political Activity: Handschu and Patrol Guide § 212-72 ....... 11 II. OIG-NYPD Investigation .............................................................................................. 12 Methodology and Access ..................................................................................................... 13 I. Treatment of Sensitive Information ............................................................................ 13 II. Compliance Criteria ..................................................................................................... 13 III. Scope and Sampling .................................................................................................... 14 -

Unlearning Liberty

LuKIANOFF “Lukianoff is an engaging exposer of the shocking repression of free speech on campus, EDUCATION / EducationaL POLICY & combining good storytelling with clear principles and a serious purpose with a light touch.” REFORM / GeneraL —STEVEN PINKER, Harvard College Professor of Psychology, Harvard University, US $25.99 / CAN $29.00 author of The Blank Slate and The Better Angels of Our Nature For over a generation, shocking cases of censor- “Unlearning Liberty is a must-read book for anyone concerned about the constitutional ship at America’s colleges and universities have future of our nation.” taught students the wrong lessons about living in a free society. Drawing on a decade of experi- —Nat HentoFF, journalist, author of Free Speech for Me—But Not for Thee ence battling for freedom of speech on campus, First Amendment lawyer Greg Lukianoff reveals “Destined to be a classic work on freedom in America.” how higher education fails to teach students to —DonaLD DOWNS, University of Wisconsin–Madison, author of Restoring Free become critical thinkers: by stifling open debate, Speech and Liberty on Campus our campuses are supercharging ideological divi- GREG LuKIANOFF is an attorney and president UN sions, promoting groupthink, and encouraging of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Edu- “Here’s a book full of sunlight—the best disinfectant for campus censorship.” an unscholarly certainty about complex issues. cation. His writings on campus free speech have —JonaTHAN Rauch, Brookings Institute, author of Kindly Inquisitors: The New appeared in the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Attacks on Free Thought L Lukianoff walks readers through the life of a Times, and the Boston Globe, in addition to dozens EARNING modern-day college student, from orientation to of other publications. -

1 What Can Labor Organizations Do for US

1 What Can Labor Organizations Do for US Workers When They Can't Do What Unions Used to Do? Abstract The traditional union model of organizing workers through representation elections and bargaining with management for higher wages and benefits is in trend decline in the US. Private sector union density has plummeted while public sector collective bargaining faces continual attacks on its legitimacy. In such a setting the only sensible answer to the title question is that unions will not accomplish much unless they find ways to impact economic outcomes outside of collective bargaining. With unions unable to do for workers what they once did, some labor activists, social entrepreneurs, and unions have pioneered strategies and tactics that engage workers and improve labor well-being without collective contracts. Modern information and communication technology offers ways to scale up some of these innovations and help restore a balance between labor and capital in the American economic system. Richard Freeman, Harvard and NBER What Works for Workers? Conference on Public Policies and Community-Based Solutions for Low- Wage Workers, Georgetown University, January 6, 2012 revision 2 The starting point for any realistic assessment of what unions can do for American workers is the recognition that the modus vivendi by which unions organize workers into majority organizations at a workplace and bargain for higher wages and benefits no longer works for most workers. If unions follow their traditional model of organizing a majority of workers at a workplace and bargaining solely for those workers while doing nothing for the predominantly nonunion work force the answer to the title question would be not much. -

THE TUFTS DAILY Est

Where You Partly Cloudy Read It First 36/21 THE TUFTS DAILY Est. 1980 VOLUME LXV, NUMBER 19 WEDNEsday, FEBRUARY 20, 2013 TUFTSDAILY.COM Friends of Israel raises $1K for children’s charity BY VICTORIA LEISTMAN Daily Editorial Board Tufts Friends of Israel (FOI) last week held its annual Valentine’s Day-themed fund- raiser to raise money for Save a Child’s Heart (SACH), an Israeli nonprofit that supports children with heart disease. FOI members were sta- tioned at tables in the Carmichael and Dewick- MacPhie Dining Centers and the Mayer Campus Center over the course of the week and collected over $1,000, FOI Co-President Aliza Shapiro said. The money raised is an improvement over the $700 to $800 raised during last year’s tabling, she said. FOI’s effort was a part of SACH’s Valentine’s Day cam- COURTESY GLYN LOWE PHOTOWORKS VIA FLICKR CREATIVE COMMONS paign across college cam- Over 35,000 people, including 30 Tufts students, gathered this past weekend in Washington D.C.’s National Mall to protest the installation of the puses nationwide to come up Keystone XL Pipeline. with $100,000 to fund 10 kids’ surgeries. “[SACH is] an Israeli-based organization that does won- Tufts environmental groups participate in derful things in terms of heart surgery and bringing treatment to medical clin- Keystone XL Pipeline protest ics in their home countries,” Shapiro, a sophomore, said. BY DANIEL GOTTFRIE D the White House, according to Tufts fosters a global climate movement, encourage his vote against the pipe- “Hopefully our increased con- Daily Editorial Board Divest for Our Future Co-Founder which led the effort to supply char- line,” Eco-Rep Evan Bell said. -

Occupy Movement”

12/5/13 Preservaon & Access of user-generated Media from Social Movements Preservaon & Access of user-generated Media from Social Movements • Why look at Occupy? • Projects from Ac-vist Archivists Howard Besser, NYU • Projects from NYU’s Tamiment Library/ hp://besser.tsoa.nyu.edu/howard Archive hFp://ac-vist-archivists.org/ Newseum 12/5/2013 1 Newseum 12/5/2013 2 We all remember Occupy Wall Street (10/17/11) the “Occupy Movement” Newseum 12/5/2013 3 Newseum 12/5/2013 4 Occupy Times Square (10/15/11) Occupy Wall Street (10/11/11) Newseum 12/5/2013 5 Newseum 12/5/2013 6 1 12/5/13 Occupy Wall Street (10/11/11) Occupy Wall Street (10/11/11) Newseum 12/5/2013 7 Newseum 12/5/2013 8 Occupy Dallas (1/21/12) Occupy DC (12/12/11) Newseum 12/5/2013 9 Newseum 12/5/2013 10 Occupy Dallas (1/20/12) Occupy Harvard (1/10/12) Newseum 12/5/2013 11 Newseum 12/5/2013 12 2 12/5/13 Occupy Finsbury Square (12/9/11) Occupy St Paul Church (12/9/11) Newseum 12/5/2013 13 Newseum 12/5/2013 14 Occupy Bristol (12/6/11) Occupy Rio (11/14/11) Newseum 12/5/2013 15 Newseum 12/5/2013 16 March 24, 2012 Flickr stats But w/all these photos & videos (just 6 months aer start of movement) floang around the Web: • “#Occupy” 632,089 • How do we know which was taken when? • “Occupy Wall Street” 164,304 • How do we find the media taken before a • “Occupy Protest” 179,454 par-cular crackdown (at that site or another)? • “Occupy Movement” 40,572 • How do we know if it’s okay to re-use one of • “#OWS” 113,904 these posted photos or videos (or even to migrate it for preservaon purposes)? -

Occupy Boston! the Guild Has Been Part of in Solidarity with the Movement

Mass Dissent Massachusetts Chapter National Lawyers Guild 14 Beacon St., Boston, MA 02108 February 2012 www.nlgmass.org Vol. 35, No. 1 In This Edition Occupy Boston! The Guild has been part of in solidarity with the movement. Occupy Boston (OB) since its Una Spenser, Occupier and very first planning meeting on active blogger on the Daily Kos, Guild News page 3 Boston Common in September. provides a firsthand account of This month's Mass Dissent the night the Boston Police NLG Holiday & New Year’s showcases a range of perspec- “arrested” the OB kitchen sink. Parties tives on the movement. All of (Read more on www.dailykos. page 4 the stories reflect the common com/user/UnaSpenser) thread of self-determination and Is there some 1% corruption Occupy Boston - from the the Guild’s respect for OB. within the Occupy Movement? Observer’s Standpoint This month's writers are just Gregory Murphy, a member of page 5 a small sample of the many, the Financial Accountability many Guild members who have Working Group, deals with the The OB “Sinkgate” put in long hours training legal betrayal of OB by some of its page 6 observers and participants; legal founding members, and tells about observing at marches, arrests, how the group resolved this issue. When I Joined the Revolution... and rallies; staying overnight at Public defenders and Guild page 7 Dewey Square; occasionally, members Chris and Carl being arrested; visiting jail and Williams answer questions NLG Members’ Work with OB - police stations at all hours to bail about their personal involve- Interview with Carl & Chris protesters out; representing ment with OB, the Guild’s con- Williams Occupiers in criminal court; fil- nection to the movement, and page 8 ing for, and briefly receiving, an discuss how OB has made the injunction; establishing an NLG Guild stronger. -

Al Franken from Saturday Night Live to the U.S

Brain Trauma • Sunset for Lectures • Into India March-april 2012 • $4.95 Al Franken From Saturday Night Live to the U.S. Senate Vice President GAIL ROBERTS 1730 Massachusetts Ave Cambridge, MA 02138 & TEAM 617 245-4044 B ELMONT , MA C AMBRIDGE , MA $3,800,000 $3,750,000 W ATERTOWN , MA C AMBRIDGE , MA $1,190,000 $2,625,000 • Recognized as one of America’s “Top 100 Real Estate Agents” by The Wall Street Journal • Connecting clients to homes & our community • Highly recommended & endorsed by clients and colleagues for exceptional integrity, commitment & performance • The right Team makes all the difference [email protected] gailrobertsrealestate.com 617 245-4044 If your property is currently listed with a real estate broker, please disregard. It is not our intention to solicit offerings of other real estate brokers. We are happy to work with them and cooperate fully. Owned and operated by NRT Incorporated.An equal Opportunity Employer Equal Housing Opportunity 120316_Coldwell_GailRoberts.indd 1 1/25/12 9:13 AM MARCH-APRIL 2012 VOLUME 114, NUMBER 4 FEATURES 23 Twilight of the Lecture Eric Mazur is an evangelist for “active learning” by Craig Lambert PETER PEREIRA page 46 DEPARTMENTS 28 Vita: Fanny Bullock Workman 4 Cambridge 02138 Brief life of a feisty mountaineer: 1859-1925 Communications from our readers by Thomas Pauly 9 Right Now Artful dodging, watching neurons at work, wind-energy entrepreneurship 30 Al Franken: You Can Call Me Senator 12A New England Regional Section From comedy to the Capitol A calendar of spring events, rigorous -

Harvard College Student and Soap and Diversity at the University

The HARVARD FOUNDATION Journal FALL 2011 HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. XXXI, NO. 1 The Sultan of Sokoto Visits Lionel Richie Honored with Harvard the Peter J. Gomes Humanitarian Award Harvard Artist in Residence: Agnes Nixon Portrait Unveiling of The Harvard Foundation Dr. Preston Williams at Harvard Divinity School and the Undergraduate Council Present Diversitas: A Celebration of Culture at Harvard In this issue: The Ivy Class: Socioeconomic Awareness Sustained Dialogue Celebrating 30 years of the Harvard Foundation 2 HARVARD FOUNDATION JOURNAL, FALL 2011 Table of Contents Harvard Foundation Journal Contents and Featured Programs p. 3 Letter from the Director p. 4-5 Lionel Richie Presented with the Peter J. Gomes Humanitarian Award p. 6-7 Portrait Unveiling of Dr. Preston Williams at the Harvard Divinity School p. 8-9 Legendary Soap Opera Creator, Agnes Nixon, Honored as Artist in Residence at Harvard p. 10-11 Diversitas: Celebrating Diversity at Harvard! p. 12-13 The Annual Harvard Foundation Freshmen Reception p. 13 The Ivy Class: Socioeconomic Diversity at Harvard p. 14 The Sultan of Sokoto Visits Harvard p. 17 Spotlight on the Harvard Foundation Interns: Fall Retreat 2011 Student Initiated Programs p. 16 Sustained Dialogue Fall 2011 News & Notes p. 15 Race Relations Advisors Activity Reports p. 15 Monthly Student/Faculty Advisory Committee Meetings p. 18- 21 Harvard Foundation Student Grant Summary Reports p. 22 Journal Articles Continued p. 22 Acknowledgements p. 23 List of Student and Faculty Advisory Committee Members On the cover, clockwise from bottom left: Dr. Preston Williams (with wife, Dr. Connie Williams) honored in portraiture at the Harvard Divinity School. -

HUPD-Report.Pdf

HARVARD ’S FINEST? THE CASE FOR THE ABOLITION OF THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY POLICE DEPARTMENT November 2020 THE CASE FOR THE ABOLITION OF THE HARVARD UNIVERSITY POLICE DEPARTMENT A report by the Harvard Alliance Against Campus Cops (HAACC) This report is authored by members of the Harvard Alliance Against Campus Cops, including: Ifea, Anand Chukkab, Iman Mohamed, Lynn Hurb, Xitlalli Alvarez Almendariz, Joan Steffen, Kiryung Kimb, Eric Cohnc, Amanda Chan, Joanna Anyanwud, Nnamdi Jogwe, Alexis Smithb, Mimi Yen Lib, Aisha Oshilaja, George Hutchinsb, Marina Multhaupd. We received invaluable assistance transcribing HUPD police logs for analysis from many additional individ- uals, including: Courtney Doughertyd, Ash Inglisa, Massiel Torres Ulloae, Julia Beatinib, and Wesley Choub. Thank you also to Sam Matthew (GSD ’18) for designing the report. This report was made possible in part through funding from the National Lawyers’ Guild. Harvard Collegea, Harvard Medical Schoolb, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Healthc, Harvard Law Schoold, Department of Romance Languages and Literaturee CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 LIST OF DEMANDS 8 WHAT WE BELIEVE & WHAT WE DEMAND 13 ALTERNATIVES TO CALLING THE POLICE 47 HISTORY OF HUPD 50 WHAT DOES HUPD DO? 88 FOLLOW THE MONEY 104 ABOLITION AS HEALTHCARE 110 HARVARD’S BLACK BOX 118 THE MORAL CASE FOR ABOLITION 122 APPENDIX: HUPD STORIES 136 found, the University profits from criminal- This is the first time that such EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ization and mass incarceration through its extensive data analysis and historical minimum $3 million of investments in the research has been conducted on HUPD. prison-industrial complex.3 Our research suggests that HUPD is a Harvard Alliance Against Campus death, HUPD officers were photographed department that operates just like all Cops (HAACC) is a coalition of students patrolling a Black Lives Matter vigil in We begin by presenting our demands, police — it doesn’t prevent harm, but and alumni demanding the abolition of Franklin Park. -

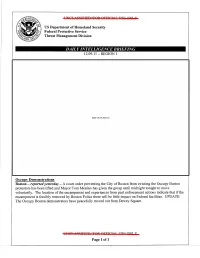

Daily Intelligence Briefing 12.09.11 - Region 1

UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY US Department of Homeland Security Federal Protective Service Threat Management Division DAILY INTELLIGENCE BRIEFING 12.09.11 - REGION 1 NON RESPONSIVE Occupy Demonstrations Boston - reported yesterday - A court order preventing the City of Boston from evicting the Occupy Boston protestors has been lifted and Mayor Tom Menino has given the group until midnight tonight to move voluntarily. The location of the encampment and experiences from past enforcement actions indicate that if the encampment is forcibly removed by Boston Police there will be little impact on Federal facilities. UPDATE: The Occupy Boston demonstrators have peacefully moved out from Dewey Square. UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Page 1 ofl UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY US Department of Homeland Security Federal Protective Service Threat Management Division . DAILY INTELLIGENCE BRIEFING 12.12.11 - REGION 1 NON RESPONSIVE Occupy Demonstrations Boston - The encampment located at Dewey Square in Boston was closed by Boston Police on Saturday morning with 46 arrests. Police stated that those arrested were nonviolent and "very accomidating" to the officers. The organization has stated that it will continue its mission, hosting meetings and demonstrations at various locations. UNCLASSIFIED//FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Page 1 ofl (b)(6), (b)(7)c From: (b)(6), (b)(7)c Sent: Tuesday, November 01, 2011 1 :19 PM To: (b)(6), (b)(7)c Cc: Subject: Occupy Products Importance: High RIAS- (b)(5) At this time, this guidance is only for Intelligence Products and does not apply to any normal operational reporting. (b)(6), (b)(7)c Special Agent Department of Homeland Security Federal Protective Service (b)(6), (b)(7)c 3/9/2012 (b)(6), (b)(7)c From: (b)(6), (b)(7)c Sent: Thursday, December 08,2011 3:06 PM To: (b)(6), (b)(7)c Subject: RE: FPS IB Absolutely. -

Duncan Kennedy on Constitutional Theory and Palestine

Duncan Kennedy on Constitutional Theory and Palestine Nimer Sultany In this brief contribution I would like to acknowledge Duncan Kennedy's influence on my thinking and work in the past years. My own work has focused on constitutional law and theory—and although this was not a primary concern of Duncan’s scholarship— in this piece I will focus on two aspects of his work and career that influenced me as his student, political ally, and friend: radical left theoretical thought and radical left practice. Indeed, this combination is the reason why many of us admire him. He is one of the few scholars who were able to commit in his long career to both projects: intellectual critique and a left-wing politics. He was able to prevent the stifling of critique by the political, and at the same time to perform critique without undermining the political. He did not fall to the trap of either the free-floating intellectual or that of the simple party member. I. From Private Law to Public Law As noted, constitutional law and theory were not a primary focus for Duncan, given the emphasis in his teaching and writing career on exposing the seemingly neutral, apolitical, and technical language of private law arrangements that structure the background conditions to societal arrangements. Building on and extending the work of the American legal realists who came before him, Duncan sought to expose the ‘unfreedom’ that permeates the supposedly private sphere of autonomous individuals who can form their choices within the shield of individual rights. These arrangements are not merely coercive; they have distributive outcomes—they produce winners and losers—and some of these outcomes may well be politically objectionable.1 This is part of his larger theoretical endeavor of critique of liberal legalism.2 There is no rational defense of the belief in liberal legality as a primary tool of advancing society towards liberal or progressive goals. -

Universidade Do Sul De Santa Catarina Manuela Da Rosa Jorge

UNIVERSIDADE DO SUL DE SANTA CATARINA MANUELA DA ROSA JORGE AS MÍDIAS SOCIAIS E O OCCUPY WALL STREET Florianópolis, 2013 MANUELA DA ROSA JORGE AS MÍDIAS SOCIAIS E O OCCUPY WALL STREET Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso apresentado ao Curso de Graduação em Relações Internacionais da Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Bacharel. Orientador: Prof. José Baltazar Salgueirinho Osório de Andrade Guerra, Dr. Florianópolis, 2013 MANUELA DA ROSA JORGE AS MÍDIAS SOCIAIS E O OCCUPY WALL STREET Este Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso foi julgado adequado à obtenção do título de Bacharel em Relações Internacionais e aprovado em sua forma final pelo Curso de Relações Internacionais da Universidade do Sul do Sul de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis, 24 de Junho de 2013. ________________________________________________________________ Prof. e orientador José Baltazar Salgueirinho Osório de Andrade Guerra, Dr. Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina ________________________________________________________________ Prof. João Batista da Silva, Msc. Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina ________________________________________________________________ Profa. Dâmaris de Oliveira B. da Silva, Msc. Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina Dedico este trabalho de conclusão de curso aos meus pais, Carolina Henriqueta e Carlos Alberto, os quais em todos os anos de minha vida, e principalmente nos anos da graduação, me apoiaram, me incentivaram a perseguir meus sonhos e a acreditar em mim mesma e me encheram de amor todos os dias, incondicionalmente. AGRADECIMENTOS Acredito que agradecer a todas as pessoas que diretamente e indiretamente contribuíram para a concretização desta minha caminhada seria um pouco longo, então serei breve e pontual, mas sem deixar de agradecer a todos aqueles que são especiais para mim, de alguma maneira.