Eastern Core (False Creek Flats) Statement of Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vancouver Early Years Program

Early Years Programs The following is a list of Early Years Programs (EYP) in the City of Vancouver. These programs offer drop-in sessions or registered programs for families to attend with young children. These programs include: A. Community Centres: A variety of programs available for registration for families and children of all ages. B. Family Places: Programs offered include drop-ins for parents, caregivers and children, peer counseling, prenatal programs, clothing exchanges, community kitchens and nutrition education. C. Neighourhood Houses: Various programs offered for all children and families, including newcomers, such as literacy, family resource programs, childcare and much more. D. Strong Start Programs: StrongStart is a free drop-in program in some Vancouver schools that is offered to parents and caregivers with children ages zero to five years old. You must register to attend. Visit Vancouver School Board website for registration information www.vsb.bc.ca/Student_Learning/Early-Learners/StrongStart. E. Vancouver Public Libraries: Public libraries are located around the City. Many programs, such as story times are offered for children, families and caregivers. Visit www.vpl.ca for hours, programs and locations. October 2018 Westcoast Child Care Resource Centre www.wccrc.ca| www.wstcoast.org A. Community Centres Centre Name Address Phone Neighourhood Website Number Britannia 1661 Napier 604-718-5800 Grandview- www.brittnniacentre.org Woodland Champlain Heights 3350 Maquinna 604-718-6575 Killarney www.champlainheightscc.ca -

For Sale Single Tenant Investment Opportunity For5650 Dunbar Sale Street | Vancouver, Bc Single Tenant Investment Opportunity 5650 Dunbar Street | Vancouver, Bc

FOR SALE SINGLE TENANT INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY FOR5650 DUNBAR SALE STREET | VANCOUVER, BC SINGLE TENANT INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY 5650 DUNBAR STREET | VANCOUVER, BC DOWNTOWN VANCOUVER ENGLISH BAY KITSILANO KERRISDALE ARBUTUS RIDGE Kerrisdale Dunbar Community Elementary Centre School West 41st Avenue Dunbar Street Crofton House PROPERTY School DUNBAR- SOUTHLANDS JACK ALLPRESS* DANNY BEN-YOSEF DAVID MORRIS* Dunbar Street 604 638 1975 604 398 5221 604 638 2123 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] *Personal Real Estate Corporation FORM RETAIL ADVISORS INC. FOR SALE SINGLE TENANT INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY 5650 DUNBAR STREET | VANCOUVER, BC PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS LOCATION A rare opportunity to purchase a prime C-2 zoned investment site with future • 10 minute drive to the University of British Columbia • Within close proximity to Dunbar Village, Kerrisdale, development upside in one of Vancouver’s most prestigious neighborhoods numerous schools, parks and golf courses • Situated in an affluent part of Vancouver with the primary trade area averaging a household income of $192,554 The Ivy by TBT Venture • Close proximity to various high profile developments Limited Partnership West Boulevard - 48 units of rental suites 4560 Dunbar by the Prince of Wales including 5555 Dunbar, The Dunbar/Kerrisdale, The - Completion Winter 2017 Harwood Group Secondary School - 59 units condo Stanton, The Kirkland, McKinnon and Sterling projects • Major retailers in the area include: Save-on-Foods, Shoppers Drug Mart and Stong’s Market Point Grey INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS Secondary Dunbar/Kerrisdale The Two Dorthies by Trasolini PROPERTY by Magellen 2020 Construction Corporation - 8 units townhouse • Single tenant property occupied by a neighbourhood 5505 Dunbar by Wesgroup liquor store, with lease running until February 2022. -

Union Station Conceptual Engineering Study

Portland Union Station Multimodal Conceptual Engineering Study Submitted to Portland Bureau of Transportation by IBI Group with LTK Engineering June 2009 This study is partially funded by the US Department of Transportation, Federal Transit Administration. IBI GROUP PORtlAND UNION STATION MultIMODAL CONceptuAL ENGINeeRING StuDY IBI Group is a multi-disciplinary consulting organization offering services in four areas of practice: Urban Land, Facilities, Transportation and Systems. We provide services from offices located strategically across the United States, Canada, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. JUNE 2009 www.ibigroup.com ii Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................... ES-1 Chapter 1: Introduction .....................................................................................1 Introduction 1 Study Purpose 2 Previous Planning Efforts 2 Study Participants 2 Study Methodology 4 Chapter 2: Existing Conditions .........................................................................6 History and Character 6 Uses and Layout 7 Physical Conditions 9 Neighborhood 10 Transportation Conditions 14 Street Classification 24 Chapter 3: Future Transportation Conditions .................................................25 Introduction 25 Intercity Rail Requirements 26 Freight Railroad Requirements 28 Future Track Utilization at Portland Union Station 29 Terminal Capacity Requirements 31 Penetration of Local Transit into Union Station 37 Transit on Union Station Tracks -

Summary 2019

Our work 2019 www.heritagevancouver.org | December 2019 www.heritagevancouver.org | December 2019 To the members & donors of Heritage Vancouver We are growing, more historic buildings important, but it’s become clear that what makes the retail of Mount focused, and dedicated Pleasant Mount Pleasant is also tied to things like small local businesses, affordable rents, to creating a diverse and the nature of lot ownership, the range of inspiring future for city. demographic mix, and the diversity in the types of shops and services. In our experience, there is a view that heritage In last year’s letter, I discussed some of the has shifted to intangible heritage versus best practice approaches starting to make its tangible heritage. way into local heritage and into the upcoming The dichotomy between intangible heritage planned update to the City of Vancouver’s and tangible heritage certainly does exist. aging heritage conservation program. But it is important to point out that this Meanwhile, the City of Vancouver’s new dichotomy was introduced in the heritage field Culture plan Culture|Shift: Blanketing the as a corrective to include the things that the city in arts and culture includes a large focus protection of great buildings did not protect or on intangible heritage, reconciliation, and recognize. culture. While what all this will look like in What may be more useful for us is that heritage policy still isn’t completely clear, what we begin to care for the interrelationships is clear is that heritage in Vancouver is and will between things that are built, and the human be undergoing great change. -

Vancouver, British Columbia Destination Guide

Vancouver, British Columbia Destination Guide Overview of Vancouver Vancouver is bustling, vibrant and diverse. This gem on Canada's west coast boasts the perfect combination of wild natural beauty and modern conveniences. Its spectacular views and awesome cityscapes are a huge lure not only for visitors but also for big productions, and it's even been nicknamed Hollywood North for its ever-present film crews. Less than a century ago, Vancouver was barely more than a town. Today, it's Canada's third largest city and more than two million people call it home. The shiny futuristic towers of Yaletown and the downtown core contrast dramatically with the snow-capped mountain backdrop, making for postcard-pretty scenes. Approximately the same size as the downtown area, the city's green heart is Canada's largest city park, Stanley Park, covering hundreds of acres filled with lush forest and crystal clear lakes. Visitors can wander the sea wall along its exterior, catch a free trolley bus tour, enjoy a horse-drawn carriage ride or visit the Vancouver Aquarium housed within the park. The city's past is preserved in historic Gastown with its cobblestone streets, famous steam-powered clock and quaint atmosphere. Neighbouring Chinatown, with its weekly market, Dr Sun Yat-Sen classical Chinese gardens and intriguing restaurants add an exotic flair. For some retail therapy or celebrity spotting, there is always the trendy Robson Street. During the winter months, snow sports are the order of the day on nearby Grouse Mountain. It's perfect for skiing and snowboarding, although the city itself gets more rain than snow. -

Viaducts | Information Boards

THE FUTURE OF VANCOUVER’S VIADUCTS Welcome to our information session on the future of Vancouver’s viaducts. Over the past two years City staff have been testing the replacement of the Georgia and Dunsmuir Viaducts. We’d like to share our findings with you and invite you to share your opinion. Why are we here today? Since 2010, City staff have been exploring opportunities to replace the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts with a mostly at-grade street network to allow for a larger Creekside Park, improved walking, cycling, transit, and driving options, a new neighbourhood and housing opportunities on city land. In September 2015, Council will consider whether to move ahead with removing the viaducts. What are we planning? Viaducts Process Timeline After Council consider the future of the viaducts in Technical Phase 1 - Viaducts Phase 2 - Viaducts September work on the future Studies neighbourhood and park will Council to consider future of the viaducts begin. Community Engagement Phase 1 - Viaducts Phase 2 - NEFC + Park It is important that we hear from the community Park+NEFC on what they think are the Planning Phase 2 - NEFC + Park opportunities and challenges posed by the replacement of Jun Jul Aug Sep Fall Spring the viaducts to inform Phase 2 2015 2016 of this work. Start Finish vancouver.ca/viaducts VANCOUVER’S VIADUCTS: THE FINDINGS There are a number of key findings City staff have learnt from studying the opportunities and challenges of replacing the viaducts. Maintaining the network capacity More Resilient Travel Time, Safety and Infrastructure The new proposed network can Comfort accommodate Improved At-grade streets are connections + more seismically resilient. -

Technical Memo 4 Proposed Bicycle Monitoring Program

TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................... ES-1 1.0 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT AND GUIDING PRINCIPLES.................................................................... 3 2.1 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FROM PRECEDING TECHNICAL MEMORANDA ..................................................................... 3 2.2 GUIDING PRINCIPLES .................................................................................................................................. 4 3.0 NEEDS DEFINITION ......................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 APPLICATIONS ........................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 CURRENT SITUATION AND GAP ANALYSIS ......................................................................................................... 8 3.3 NEEDS ANALYSIS ...................................................................................................................................... 10 3.4 SUMMARY OF NEEDS ................................................................................................................................ 13 4.0 ASSESSMENT INDICATORS & EVALUATION FRAMEWORK ........................................................... -

For Lease M Re 425 Carrall Street Mercial Premier Gastown Office Opportunities the Old Bc Electric Building

,VAN WN CO O T U S V A E R G C O E gt T R A B T S E E L CO AL FOR LEASE M RE 425 CARRALL STREET MERCIAL PREMIER GASTOWN OFFICE OPPORTUNITIES THE OLD BC ELECTRIC BUILDING ROBERT THAM MARC SAUL* WILLOW KING [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 604.609.0882 x 223 604.609.0882 x 222 604.609.0882 x 221 *Personal Real Estate Corporation CORBEL COMMERCIAL REAL ESTATE SERVICES 632 Citadel Parade, Vancouver, BC, V6B 1X3 T:604.609.0882 | F:604.609.0886 www.corbelcommercial.com E. & O. E.: All information contained herein is from sources we deem reliable, and we have no reason to doubt its accuracy; however, no guarantee or responsibility is assumed thereof, and it shall not form any part of future contracts. Properties are submitted subject to errors and omissions and all information should be carefully verifi ed. All measurements quoted herein are approximate. 425 CARRALL STREET LOCATION The landmark property is ideally located at the corner of Carrall Street and West Hastings Street at the confluence of the Gastown and Chinatown districts in downtown Vancouver. Gastown is a preserved heritage zone adjacent to Vancouver’s financial core. The area is intersected by many transit routes, and is in close proximity to the SeaBus terminal, Stadium-Chinatown SkyTrain Station and the West Coast Express. The Old BC Electric Building is a strategically located character building which has been recently renovated to add contemporary improvements to its historical charm. Several new and popular restaurants and cafés, including L’Abattoir, Save-On-Meats, Tacofino, and PiDGiN, are located in the immediate area. -

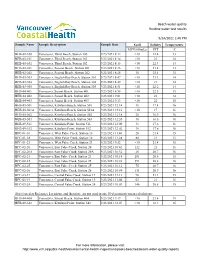

Beach Water Quality Routine Water Test Results 9/3/2021 1:05 PM

Beach water quality Routine water test results 9/24/2021 1:46 PM Sample Name Sample Description Sample Date Ecoli Salinity Temperature MPN/100mLs PPT °C BEB-01-100 Vancouver, Third Beach, Station 100 9/23/2021 8:12 <10 22.4 13 BEB-01-101 Vancouver, Third Beach, Station 101 9/23/2021 8:14 <10 23 14 BEB-01-102 Vancouver, Third Beach, Station 102 9/23/2021 8:16 <10 22.4 14 BEB-02-201 Vancouver, Second Beach, Station 201 9/23/2021 8:26 <10 23.4 13 BEB-02-202 Vancouver, Second Beach, Station 202 9/23/2021 8:28 10 25.3 13 BEB-03-303 Vancouver, English Bay Beach, Station 303 9/23/2021 8:47 <10 21.3 14 BEB-03-304 Vancouver, English Bay Beach, Station 304 9/23/2021 8:49 <10 21 14 BEB-03-305 Vancouver, English Bay Beach, Station 305 9/23/2021 8:51 <10 22.2 14 BEB-04-401 Vancouver, Sunset Beach, Station 401 9/23/2021 8:58 <10 22.5 15 BEB-04-402 Vancouver, Sunset Beach, Station 402 9/23/2021 9:01 <10 22 14 BEB-04-403 Vancouver, Sunset Beach, Station 403 9/23/2021 9:13 <10 22 15 BEB-05-501 Vancouver, Kitsilano Beach, Station 501 9/23/2021 12:14 10 17.4 16 BEB-05-501A Vancouver, Kitsilano Beach, Station 501A 9/23/2021 12:16 <10 17 16 BEB-05-502 Vancouver, Kitsilano Beach, Station 502 9/23/2021 12:18 20 16.9 16 BEB-05-503 Vancouver, Kitsilano Beach, Station 503 9/23/2021 12:20 10 16.6 16 BEB-09-511 Vancouver, Kitsilano Point, Station 511 9/23/2021 12:00 31 17.6 16 BEB-09-512 Vancouver, Kitsilano Point, Station 512 9/23/2021 12:02 10 17.6 16 BFC-01-16 Vancouver, West False Creek, Station 16 9/23/2021 11:46 20 21.4 15 BFC-01-18 Vancouver, West False Creek, -

Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver

Erasing Indigenous Indigeneity in Vancouver J EAN BARMAN1 anada has become increasingly urban. More and more people choose to live in cities and towns. Under a fifth did so in 1871, according to the first census to be held after Canada C 1867 1901 was formed in . The proportion surpassed a third by , was over half by 1951, and reached 80 percent by 2001.2 Urbanization has not benefited Canadians in equal measure. The most adversely affected have been indigenous peoples. Two reasons intersect: first, the reserves confining those deemed to be status Indians are scattered across the country, meaning lives are increasingly isolated from a fairly concentrated urban mainstream; and second, the handful of reserves in more densely populated areas early on became coveted by newcomers, who sought to wrest them away by licit or illicit means. The pressure became so great that in 1911 the federal government passed legislation making it possible to do so. This article focuses on the second of these two reasons. The city we know as Vancouver is a relatively late creation, originating in 1886 as the western terminus of the transcontinental rail line. Until then, Burrard Inlet, on whose south shore Vancouver sits, was home to a handful of newcomers alongside Squamish and Musqueam peoples who used the area’s resources for sustenance. A hundred and twenty years later, apart from the hidden-away Musqueam Reserve, that indigenous presence has disappeared. 1 This article originated as a paper presented to the Canadian Historical Association, May 2007. I am grateful to all those who commented on it and to Robert A.J. -

Vancouver British Columbia

ATTRACTIONS | DINING | SHOPPING | EVENTS | MAPS VISITORS’ CHOICE Vancouver British Columbia SUMMER 2017 visitorschoice.com COMPLIMENTARY Top of Vancouver Revolving Restaurant FINE DINING 560 FEET ABOVE SEA LEVEL! Continental Cuisine with fresh seafood Open Daily Lunch, Dinner & Sunday Brunch 555 West Hastings Street • Reservations 604-669-2220 www.topofvancouver.com No elevator charge for restaurant patrons Top of Vancouver VSp16 fp.indd 1 3/13/16 7:00:35 PM 24 LEARN,LEARN, EXPLOREEXPLORE && SAVESAVE UUPP TTOO $1000.00$1000.00 LEARN,History of Vancouver, EXPLORE Explore 60+ Attractions, & SAVE Valid 2 Adults UP & T2 ChildrenO $1000.00 ( 12 & under) TOURISM PRESS RELEASE – FALL 2 016 History of Vancouver, Explore 60+ Attractions, Valid 2 Adults & 2 Children (12 & under) History of Vancouver, Explore 60+ Attractions, Valid 2 Adults & 2 Children ( 12 & under) “CITY PASSPORT CAN SAVE YOUR MARRIAGE” If you are like me when you visit a city with the family, you always look to keep everyone happy by keeping the kids happy, the wife happy, basi- cally everybody happy! The Day starts early: “forget the hair dryer, Purchase Vancouver’s Attraction Passport™ and Save! we’ve got a tour bus to catch”. Or “Let’s go to PurchasePurchase Vancouver’s Vancouver’s AttractionAttraction Passport™Passport™ aandnd SSave!ave! the Aquarium, get there early”, “grab the Trolley BOPurNUS:ch Overase 30 Free VancTickets ( 2ou for 1 veoffersr’s ) at top Attr Attractions,acti Museums,on P Rassestaurants,port™ Vancouve ar Lookout,nd S Drave. Sun Yat! BONUS:BONUS Over: Ove 30r 30 Free Free Tickets Tickets ( (2 2 for fo r1 1 offers offers ) )at at top top Attractions, Attractions, Museums, RRestaurants,estaurants, VVancouverancouver Lookout, Lookout, Dr Dr. -

RAIL SAFETY WEEK April 24 – 30 2017 Calendar of Events for CANADA

RAIL SAFETY WEEK April 24 – 30 2017 Calendar of Events for CANADA Province City/Town Event Date Event Time Event Details Name of Location and Address PACIFIC DIVISION British Columbia Surrey Monday, April 24 11 am to 2 pm Kick-Off BBQ CN Police Office 11717 - 138th St, Surrey (Bldg. E) British Columbia Vanderhoof Monday, April 24 10 am to 12 pm Grade Crossing Enforcement Mile 69.7 Nechako Sub. - Sliversmith Crossing CNPS & 1st Nations By-Law – Chilcotin Rd.are through British Columbia Kamloops Monday April 24 9 am to 11 am Trespass Enforcement reserve. 950 E. Cordova & Raymur Ave., 1043 Union Street & British Columbia Vancouver Tuesday, April 25 10 am to 2:30 pm Grade Crossing Enforcement Glen Drive, 1033 Venables St. & Glen Drive, 1040 Parker Street & Glen Drive, Vancouver, BC (Railway Crossings) British Columbia Prince George Tuesday, April 25 10 am to noon Grade Crossing Enforcement Mile 460 Prince George Sub. - Boundary Road Crossing HRA Mile 2-3 Okanagan Sub including Rail Bridge at Stn British Columbia Kamloops Tuesday, April 25 10 am to 2 pm Trespass Enforcement Plaza Rd in Kamloops Youth safety Summit O.L. Northwest Community College, 5331 McConnell Ave., British Columbia Terrace Tuesday April 25 12:40 to 1:45 pm Presentations 4-5 Terrace No. 5 Rd North to No 5 Rd. South & Nelson & Blundell British Columbia Richmond Tuesday April 25 10 am to 3 pm Crossing Enforcement Rd. area. Officer on the Train & Crossing Several crossings on Shell Road and no 5 Road in British Columbia Richmond Wednesday, April 26 9 am to noon Enforcement Richmond British Columbia Burns Lake Wednesday, April 26 10 am to noon Trespass Enforcement Telkwa Sub.