Mondo Formaggio.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Price List - Cook School

PRICE LIST - COOK SCHOOL TO PLACE AN ORDER: CALL US ON 01563 55008 OPTION 1 BETWEEN 8AM AND 12PM DAILY, COLLECT FROM 1PM TO 8PM THE SAME DAY. COLLECT FROM BRAEHEAD FOODS WAREHOUSE, TO THE REAR OF BRAEHEAD FOODS/COOK SCHOOL. MINIMUM ORDER VALUE £35, MAXIMUM 1 BOX OF CHICKEN PP. Production Kitchen - Buffet Canape & Starters Product No Product Description UOM Sub Category Column1 Price SHOP041 CS SHOP STEAK & SAUSAGE PIE 1.2 KG EACH £11.00 SHOP048 CCS READY MEAL MINCE POTATOES PEAS AND CARROTS 345 G EACH £3.00 SHOP052 CSS READY MEAL LASAGNE 500G EACH £5.00 SHOP054 CSS READY MEALS CHICKEN BROCCOLI & PASTA BAKE 450 G EACH £4.00 SHOP058 CSS READY MEALS MACARONI CHEESE 400G EACH £3.00 Production Kitchen - Burgers Product No Product Description UOM Sub Category Column1 Price PRO01895 BHF VENISON BURGER 5 x 170g (Frozen) EACH PK Burgers £13.20 Production Kitchen - Hot Wets Product No Product Description UOM Sub Category Column1 Price PRO02003 BHF WHL BEEF & SMOKED PAPRIKA MEATBALLS IN TOMATO SAUCE 2.5Kg (Frozen)EACH Pre 10 PK Hot Wets £28.01 PRO02042 BHF BEEF LASAGNE 2.5Kg (FROZEN) EACH PK Hot Wets £27.64 PRO02015 BHF CAULIFLOWER MAC & CHEESE CRUMBLE 2.5Kg (Frozen) (Vegetarian) Pre 10EACH PK Hot Wets £24.07 PRO02019 BHF CHICK PEA, SQUASH & VEGETABLE CURRY 2.5Kg (Frozen) (Vegetarian) PreEACH 10 PK Hot Wets £21.69 PRO02004 BHF CHICKEN CASSEROLE WITH HERB DUMPLINGS 2.5Kg (Frozen) Pre 10 EACH PK Hot Wets £29.44 PRO02005 BHF CHICKEN TIKKA MASALA CURRY 2.5Kg (Frozen) Pre 10 EACH PK Hot Wets £25.36 PRO02006 BHF CHICKEN, CHICK PEA & CORIANDER TAGINE 2.5Kg -

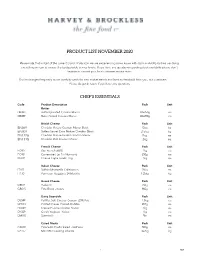

Copy of Product List November 2020

PRODUCT LIST NOVEMBER 2020 Please note that in light of the current Covid-19 situation we are experiencing some issues with stock availability but we are doing everything we can to ensure the best possible service levels. If you have any questions regarding stock availability please don't hesitate to contact your local customer service team. Our list changes frequently as we carefully watch for new market trends and listen to feedback from you, our customers. Please do get in touch if you have any questions. CHEF'S ESSENTIALS Code Product Description Pack Unit Butter DB083 Butter Unsalted Croxton Manor 40x250g ea DB089 Butter Salted Croxton Manor 40x250g ea British Cheese Pack Unit EN069 Cheddar Mature Croxton Manor Block 5kg kg EN003 Butlers Secret Extra Mature Cheddar Block 2.5kg kg EN127G Cheddar Mature Grated Croxton Manor 2kg ea EN131G Cheddar Mild Croxton Manor 2kg ea French Cheese Pack Unit FC417 Brie French (60%) 1kg ea FC431 Camembert Le Fin Normand 250g ea FG021 Chevre Capra Goats' Log 1kg ea Italian Cheese Pack Unit IT042 Buffalo Mozzarella Collebianco 200g ea IT130 Parmesan Reggiano 24 Months 1.25kg kg Greek Cheese Pack Unit GR021 Halloumi 250g ea GR015 Feta Block - Kolios 900g ea Dairy Essentials Pack Unit DS049 Full Fat Soft Cheese Croxton (25% Fat) 1.5kg ea DC033 Clotted Cream Cornish Roddas 907g ea DC049 Crème Fraîche Croxton Manor 2kg ea DY009 Greek Yoghurt - Kolios 1kg ea DM013 Buttermilk 5ltr ea Cured Meats Pack Unit CA049 Prosciutto Crudo Sliced - Dell'ami 500g ea CA177 Mini BBQ Cooking Chorizo 3x2kg kg 1 HBX Chocolate -

2022/23 Complete Wedding Service

2022/23 COMPLETE WEDDING SERVICE 01443 665803 | www.valeresort.com YOUR WEDDING ONE PRICE. EVERYTHING INCLUDED Congratulations, you are about to embark on one of the most memorable events in your life - your wedding. Naturally, nothing less than perfection will do and a whole host of exciting decisions lie before you; the dress, the flowers, the honeymoon and of course, the venue. We’ll help you celebrate the most memorable day of your life in one of the most beautiful wedding venues in Wales. The idyllic setting, exquisite landscaped gardens, sweeping staircases and classic terraces inspire beautiful photography and a day that you’ll cherish and remember for years to come. We cater for your reception with versatile rooms that create the right atmosphere - from intimate, romantic gatherings to show-stopping, lavish celebrations. The stunning Morgannwg Suite opens onto a balcony with sweeping staircases to the terrace below, and beautiful landscaped gardens that provide the ideal backdrop for your photographs. By contrast, the impressive Castle Suite offers a lavish celebration in a dramatic setting with high ceilings, wall to floor windows plus an exclusive bar and balcony terrace for you and your guests. For smaller wedding parties, the Pendoylan Suite, Cowbridge Lounge and Hensol Suite offer the right ambience for intimate gatherings while still guaranteeing a day to remember! 01443 665803 | www.valeresort.com WEDDING CEREMONY Exchanging your vows in a beautiful setting makes those precious words even more special. Our superb choice of function suites enables you to select the perfect setting to say “I do”. Whether your ceremony is an intimate gathering or a celebration for 400 guests, our civil ceremony license allows you to enjoy every aspect of your special day here at the Vale Resort. -

F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T

D E L I V E R I N G F I N E C H E E S E C R E S S C O 2018 F I N E C H S & O U T R 1 F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 8 F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 8 U S E F U L I N F O R M A T I O N C O N T E N T S Your area manager : Mobile Telephone : H A R D & S O F T B R I T I S H C H E E S E 04 Minimum Order Your office contact: B R I T I S H for Carriage Paid Office Telephone: 0345 307 3454 B L U E C H E E S E 10 G O A T S & E W E S Pallet Delivery £400£350 Office email: [email protected] M I L K C H E E S E 12 Own Vehicles £125 Office fax number : 08706 221 636 C H E E S E Pallet Delivery £600£500 I N F O R M A T I O N 15 Your order to be in by: Pallet Delivery £1000 C E L E B R A T I O N Pre-orders to be in by: Monday 12 noon C O N T E S & I F R M A C H E E S E 16 Pallet Delivery £450 Minimum order : C O N T I N E N T A L (minimum orders can be made up of a combination of product from chilled C H E E S E 17 retail and ambient) C A T E R I N G C H E E S E & D A I R Y 22 Delivery day: R E T A I L C H E E S E 24 Please note all prices are subject to fluctuation and all products are subject to availability C H A R C U T E R I E & M E A T S 27 C A N‘ T F I N D W H A T Y O U W A N T ? O L I V E S Can’t find the cheese you want? Looking for a different size? & A N T I P A S T I 31 We have put together a great variety of British and Continental Cheeses, however if there is something special you are looking for and can’t find it in the catalogue then give us a call and we will source it for you. -

F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T

F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 9 F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 9 F I N E C H E E S E & C O U N T E R 2 0 1 9 U S E F U L I N F O R M A T I O N C O N T E N T S Your area manager : S = Stock Items RECOMMENDATIONS 4 Mobile Telephone : Any item that is held in stock can be ordered up until 12 noon and will arrive on your usual delivery day. CELEBRATION CHEESE 6 Your office contact: Office Telephone: 0345 307 3454 PO = Pre-order Items SCOTTISH CHEESE 8 Cheese & Deli Team : 01383 668375 Pre-order items need to be ordered by 12 noon on a Monday and will be ready from Thursday and delivered to ENGLISH CHEESE 12 Office email: [email protected] you on your next scheduled delivery day. Office fax number : 08706 221 636 WELSH & IRISH CHEESE 18 PO **= Pre-order Items Your order to be in by: Pre-order items recommended for deliveries arriving CONTINENTAL CHEESE 20 Pre-orders to be in by: Monday 12 noon Thursday and Friday only CATERING CHEESE, 24 Minimum order : ** = Special Order Items DAIRY & BUTTER (minimum orders can be made up of a combination of Special order items (such as whole cheeses for celebration product from chilled retail and ambient) cakes) need to be ordered on Monday by 12 noon week 1 CHARCUTERIE, MEATS & DELI 26 for delivery week 2. -

Party Catering to Collect Autumn/Winter 2015/2016

PARTYPARTY CATERING CATERING TO COLLECTTO COLLECT AUTUMN/WINTERSPRING/SUMMER 2015/2016 2013 wwwww.athomecatering.co.ukw.athomecatering.co.uk CONTENTS BREAKFAST MENU (Minimum 10 covers) Contents Page PASTRY SELECTION £4.75 per person Miniature Croissant Miniature Pain au Raisin Breakfast menu 1 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Overstuffed sandwiches & sweet treats 2 - 3 CONTINENTAL £7.50 per person Freshly made salads 4 - 7 Miniature Croissant Miniature Pain au Raisin Fresh home made soups 8 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Baguette with Butter & Preserves Luxury soups, stocks & pasta sauces 9 Seasonal Fruits Cocktail/finger food 10 - 11 Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Starters & buffet dishes 12 - 13 EUROPEAN £9.50 per person Miniature Croissant Quiches & savoury tarts 14 Miniature Pain au Raisin Frittatas & savoury items 15 Miniature Pain au Chocolat Baguette & Focaccia with Butter & Preserves Chicken dishes 16 - 17 Serrano Ham with Caperberries & Olives Manchego cheese with Cherry Tomatoes & Cornichons Beef dishes 18 - 19 Muesli with Greek yogurt, Honey & Almonds Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Lamb dishes 20 - 21 Pork 22 AMERICAN £11.50 per person Miniature Croissant Duck & game 23 Miniature Pain au Raisin Miniature Pain au Chocolat Fish & seafood dishes 24 - 25 Lemon, Honey & Poppy seed Muffins Vegetarian dishes 26 Blueberry Muffins Poppy seed Bagels with Smoked Salmon, Cream cheese, Lemon & Chives Vegetable side dishes 27 Maple Cured bacon & Tomato rolls Fruit salad with Fromage Frais Whole puddings 28 - 29 Freshly squeezed Orange Juice Individual -

Hamish Johnston Fine Cheeses Wholesale Catalogue 1St July 2017

Hamish Johnston Fine Cheeses Wholesale Catalogue 1st July 2017 London Suffolk 48 Northcote Road Unit 51 London Martlesham Creek SW11 1PA Sandy Lane Martlesham IP12 4SD Phone: 020 7738 0741 Phone: 01394 388127 Fax: 020 7924 6193 Fax: 01394 446010 email: [email protected] Please note that the following are our current terms and conditions of sale. 1. Products will be invoiced at prices ruling on the day of dispatch. Whilst every effort will be made to give customers advance warning of price changes “Hamish Johnston Ltd” reserves the right to alter prices without prior notice. 2. Pre-Packed and hand wrapped cheese portions are subject to a surcharge of 25% above normal wholesale prices. 3. Any defective or out of condition stock will only be credited or replaced if we are informed within 24 hours of their delivery. All such goods must be returned to us or made available for inspection. 4. Title to the goods shall only pass to the buyer after full payment has been made to, and accepted by “Hamish Johnston Ltd”. 5. The Seller reserves the right to repossess any Goods in respect of which payment is overdue and thereafter to re-sell the same and for this purpose the Buyer hereby grants an irrevocable right and licence to the Sellers servant and agents to enter upon all or any of its premises with or without vehicles during normal business hours. This right shall continue to subsist notwithstanding the termination or cancellation of the order for any reason and is without prejudice to any accrued rights of the Seller thereunder or otherwise. -

Wedding Packages

2022/23 COMPLETE WEDDING SERVICE 01443 665803 | www.hensolcastle.com YOUR CASTLE AWAITS A 17th Century Grade 1 listed castle, exclusively yours‡ for your special day. Situated in a breathtaking estate that contains a stunning 15 acre Serpentine Lake and soaring trees. Hensol Castle is the perfect setting for any bride wanting a fairytale wedding. The lake and gardens, turreted castle, sweeping staircases and castle reception rooms provide the most memorable photogenic opportunities imaginable and that’s not all... WITH OUR COMPLIMENTS ♥ Exclusively yours for the day‡ ♥ Red carpet on arrival ♥ Silver cake stand and knife ♥ Complimentary table menus ♥ Complimentary bedroom at the Vale Resort for the happy couple ♥ One months complimentary use of our Health and Racquets Club ♥ Round of golf for the groom and three friends† ♥ 20% spa discount for the bride, one month prior to your wedding ♥ Complimentary parking ♥ Complimentary dinner on your first anniversary †Handicap certificates required. ‡Only one wedding per day at the venue. 01443 665803 | www.hensolcastle.com WEDDING BREAKFAST SANDRINGHAM £48.95 per person STARTERS Roasted Plum Tomato and Pimento Bisque VG Grilled foccacia, crisp basil Pork Belly and Confit Duck Rillettes Spiced apple chutney, grilled sourdough toast Hot Smoked Salmon Tian Dill crème fraiche and fresh horseradish Feta, Olive and Mediterranean Vegetable Tart V Pickled red onion, tzatziki, shaved cucumber ribbons MAIN COURSE Pan Roasted Chicken Breast G Olive and chorizo sauce, whipped potatoes, braised kale Pave of -

View Our Brochure

www.braeheadfoods.co.uk "Braehead Foods have been huge supporters of the industry for many years; their contribution to many of our events has enabled us to provide multiple scholars for the emerging talent for our Industry. How to The opportunities that Braehead Foods have provided for the industry have allowed great learning experience for place an order individuals to take both locally, nationally & internationally. We are very grateful for their support." Contact us on - David Cochrane t: +44 (0)1563 550 008 HIT Scotland e: [email protected] www.braeheadfoods.co.uk 7 Moorfield Park, Kilmarnock, Ayrshire KA2 OFE @Braehead_Foods @BraeheadFoods BraeheadFoodsLimited BraeheadFoods Our delivery frequency varies between 4 to 6 days a week across the UK. Please speak to our Customer Service Team to check out your own specific distribution service. Why choose Braehead Foods? Quality About us... Braehead Foods is one of Scotland’s largest Service independent food wholesalers who have been Traceability supplying Chefs across the UK and Europe with the finest quality ingredients for over 30 years. Innovation Supplying everything from the finest Scottish game to quality Reliability chilled, ambient and frozen foods, we deliver across the UK daily. Processing game birds in our AA Grade BRC Accredited Site, we can accommodate various finishing styles whether its oven ready, long legged or breast meat. As members of the British Game Alliance, Braehead Foods not only support the wild game industry, but are part of a quality assured programme where all steps from field to plate are being carried out in a safe and legal manner, ensuring compliance throughout. -

Food Safety, Production Modernisation and Origin Link Under EU Quality Schemes

Food Safety, Production Modernisation and Origin Link under EU Quality Schemes. A case study on Food Safety and Production Modernisation role and their interference with the origin link of quality scheme cheese products originating from Greece, Italy and United Kingdom. Papadopoulou Maria September 2015-June 2017 Law and Governance Group (LAW) i | P a g e Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my MSc thesis first supervisor, Dr. Mrs. Hanna Schebesta, for her valuable insights, support and understanding during the whole project, from the very first moment that I shyly delineated the idea for this project in my mind till the completion of the present paper one and a half years later. I would also like to express my grateful regards to my MSc thesis second supervisor, Dr. Mr. Dirk Roep, that it was under his course “Origin Food” in spring of 2015 that I first came up with the idea of writing for the interactions of food safety and origin foods and who corresponded so positively to my call to be my second supervisor and who supported me with his knowledge on origin foods and rural sociology, scientific fields unknown to me till recently. Many thanks to all colleagues of Law & Governance group of Wageningen University in 2015 that where happy and willing to discussed my concerns on the early steps of this project and that where present in both my Research proposal & Thesis presentation with their constructive remarks. Special thanks to MSc and PhD students of Law & Governance group in late 2015 that accompanied my research work in the Law & Governance group corridor in Leeuwenborgh building of Wageningen University. -

Food English Revival

INSIDER Stichelton Dairy partners Joe Schneider (left) and Randolph Hodgson at Collingthwaite Farm, in Nottinghamshire, with wheels of their aged cheese. ENGLAND FOOD ENGLISH REVIVAL Ever heard of Stichelton? Follow Paul Levy on his quest to find the artisans who are bringing the classic cheese (formerly known as Stilton) back to life. 66 DECEMBER 2009 | TRAVELANDLEISURE . COM Photographed by ANDREW MONTGOMERY INSIDER | FOOD Stichelton, a British raw cow’s-milk cheese made on Collingthwaite Farm, above left. Right: A herd of Holstein-Friesian cows grazing on the farm. HY AM I HERE IN NOTTINGHAMSHIRE , tastings of “artisanal” renditions such as Colston Bassett and wearing blue plastic overshoes, a Cropwell Bishop confirmed it.T he cheese had become dry matching plastic raincoat, and a and crumbly in the center, not moistly unctuous and buttery, hairnet? I am standing in a near-sterile and the subtle, fruity flavors that marked the aftertaste of old dairy, on a mission to find one of Stilton were gone, replaced by a one-dimensional salty note. Britain’s greatest delicacies, a cheese As if this weren’t bad enough, thanks to lobbying by the Wthat I thought had become extinct. This is a tale of loss and Stilton Cheesemakers’ Association, the genuine article could rebirth involving an expatriate American, a stubborn Brit, never be made and marketed again under the name Stilton and a cheese filled with history. because only pasteurized milk could be used. In Britain, Christmas used to mean turkey, plum Three years ago at a birthday party given by a friend in pudding, and a course of creamy, blue-veined Stilton, a raw London, dinner finished with a cheese that not only looked cow’s-milk cheese with a whispered tang of acidity. -

Eggs Butter Milk Bread from Our Fridge Pots Fermented

FRESH EGGS FROM OUR PINNEYS Free range eggs FRIDGE Smoked salmon 6 pack | £1.25 Local raw cream 114g | £5.50 Blackmore blue eggs 250ml | £1.65 Smoked salmon £2.50 Crème fraiche 227g | £9.95 Blackmore brown eggs 200g | £1.50 Smoked salmon paté £2.50 Ricotta £4.95 Quail eggs 250g | £2.00 Smoked fish paté £2.95 Mascapone £4.50 250g | £2.50 BUTTER Full fat soft cheese PALFREY Salted butter block 200g | £1.50 AND HALL Cottage cheese £2.00 Prices vary dependent 250g | £1.40 Unsalted butter block on weight £2.00 Cottage cheese with chives 250g | £1.40 Bungay raw butter Unsmoked back bacon Collier’s extra mature £4.50 £3 to £4 cheddar block Smoked back bacon 350g | £3.95 MILK £3 to £4 Collier’s extra mature Suffolk black back bacon Local semi skimmed milk cheddar bulk block £3 to £4 1 litre | £1.25 Approx. 1.25kg | £10.00 Smoked streaky bacon Local whole milk Mozzarella ball £3 to £4 1 litre | £1.25 £1.25 Suffolk black streaky bacon Buffalo mozzarella £3 to £4 BREAD £2.50 White farmhouse loaf Halloumi Small | £1.10 £2.95 Granary farmhouse loaf Small | £1.10 POTS Wholemeal farmhouse loaf Houmous Small | £1.10 250g | £2.50 White sliced loaf Taramasalata Large | £1.90 250g | £2.50 Granary sliced loaf Large | £1.90 FERMENTED Olive and oregano bread Kimchi £2.00 £4.95 Seeded cob Kraut £1.70 £4.50 THE ESSENTIALS BLACK DOG BUTTERWORTHS CAWSTON APIARIES TEA PRESS Oat and honey English breakfast -Apple juice Granola | £3.95 Teabags | £3.75 -Apple and elderflower Honey fruit and nut Earl grey -Apple and rhubarb juice Granola | £3.95 Teabags | £4.50 -Apple