Dohey 1 Shakespeare's Roman Honour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language and the Internet

This page intentionally left blank Language and the Internet David Crystal investigates the nature of the impact which the Internet is making on language. There is already a widespread popular mythology that the Internet is going to be bad for the future of language – that technospeak will rule, standards be lost, and creativity diminished as globalization imposes sameness. The argument of this book is the reverse: that the Internet is in fact enabling a dramatic expansion to take place in the range and variety of language, and is providing unprecedented opportunities for personal creativity. The Internet has now been around long enough for us to ‘take a view’ about the way in which it is being shaped by and is shaping language and languages, and there is no one better placed than David Crystal to take that view. His book is written to be accessible to anyone who has used the Internet and who has an interest in language issues. DAVID CRYSTAL is one of the world’s foremost authorities on language, and as editor of the Cambridge Encyclopedia database he has used the Internet for research purposes from its earliest manifestations. His work for a high technology company involved him in the development of an information classification system with several Internet applications, and he has extensive professional experience of Web issues. Professor Crystal is author of the hugely successful Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (1987; second edition 1997), Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language (1995), English as a Global Language (1997), and Language Death (2000). An internationally renowned writer, journal editor, lecturer and broadcaster, he received an OBE in 1995 for his services to the English language. -

Reimagining a Midsummer Night's Dream

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 1 Art That Lives 2 Bard’s Bio 2 The First Folio 3 Shakespeare’s England 4 The Renaissance Theater 5 Barbara Gaines Criss Henderson Courtyard-style Theater 6 Artistic Director Executive Director On the Road: A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 8 Timeline 10 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater dedi- cated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Shakespeare’s Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style courtyard theater, 500 seats on three A Midsummer Night's Dream levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also features a Dramatis Personae 12 flexible 180-seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Center, and The Story 13 Who's Who: What's in a Name? 13 a Shakespeare specialty bookstall. Act-by-Act Synopsis 14 Now in its twenty-seventh season, the Theater has produced nearly the en- Something Borrowed, Something New… tire Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends Well, Antony and Cleopa- Shakespeare's Sources 15 tra, As You Like It, The Comedy of Errors, Cymbeline, Hamlet, Henry The Nature of Comedy 17 IV Parts 1 and 2, Henry V, Henry VI Parts 1, 2 and 3, Henry VIII, Julius A History of Dreams 18 Caesar, King John, King Lear, Love’s Labor’s Lost, Macbeth, Measure Scholars’ Perspectives for Measure, The Merchant of Venice, The Merry Wives of Windsor, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Othello, Pericles, Spirits of Another Sort 20 Richard II, Richard III, Romeo and Juliet, The Taming of the Shrew, The What the Critics Say 21 Tempest, Timon of Athens, Troilus and Cressida, Twelfth Night, The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and The Winter’s Tale. -

Reading the Theatrical Nebentext in Ben Jonson's Workes As

From directions to descriptions: Reading the theatrical Nebentext in Ben Jonson’s Workes as an authorial outlet David J. Amelang Freie Universität Berlin, Germany ABSTRACT This article explores how certain dramatists in early modern England and in Spain, specifically Ben Jonson and Miguel de Cervantes (with much more emphasis on the former), pursued authority over texts by claiming as their own a new realm which had not been available—or, more accurately, as prominently available—to playwrights before: the stage directions in printed plays. The way both these playwrights and/or their publishers dealt with the transcription of stage directions provides perhaps the clearest example of a theatrical convention translated into the realm of readership. KEYWORDS: William Shakespeare; Ben Jonson; Lope de Vega; Miguel de Cervantes; stage directions. De indicaciones a descripciones: la De indicações a descrições: ler o Neben- lectura del Nebentext teatral en las text teatral em Workes de Ben Jonson Workes de Ben Jonson como expresión como expressão autoral* autorial RESUMEN: Este artículo analiza cómo RESUMO: Este artigo explora de que ciertos dramaturgos en las Inglaterra y forma certos dramaturgos em Inglaterra España del Renacimiento, especialmente e na Espanha do Renascimento, especi- Ben Jonson (y en menor medida tam- ficamente Ben Jonson e Miguel de Cer- bién Miguel de Cervantes), buscaron vantes (com maior ênfase no primeiro), establecer su posición autorial sobre sus procuraram estabelecer uma posição textos de una manera no disponible autoral sobre os seus textos ao reclama- hasta ese momento (o al menos no tan rem para si uma área que anteriormente claramente disponible) para escritores não estava disponível—ou, de forma de teatro: en las acotaciones escénicas de mais correta, não tão claramente dispo- las versiones impresas de sus obras. -

Chicago Shakespeare Theater Is Chicago’S Professional Theater Dedicated Timeline 12 to the Works of William Shakespeare

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 1 Art That Lives 2 Bard’s Bio 3 The First Folio 4 Shakespeare’s England 4 The English Renaissance Theater 6 Barbara Gaines Criss Henderson Courtyard-style Theater 8 Artistic Director Executive Director On the Road: A Brief History of Touring Shakespeare 9 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago’s professional theater dedicated Timeline 12 to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” In its Elizabethan-style courtyard theater, 500 seats on three levels wrap around a deep thrust stage—with only nine rows separating the farthest Dramatis Personae 14 seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also features a flexible 180-seat The Story 15 black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Center, and a Shakespeare Act-by-Act Synopsis 15 specialty bookstall. Something Borrowed, Something New: Shakespeare’s Sources 17 Now in its twenty-eighth season, the Theater has produced nearly the entire 1606 and All That 18 Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends Well, Antony and Cleopatra, Shakespeare, Tragedy and Us 20 As You Like It, The Comedy of Errors, Cymbeline, Hamlet, Henry IV A Scholar’s Perspective: Hereafter 21 Parts 1 and 2, Henry V, Henry VI Parts 1, 2 and 3, Henry VIII, Julius What the Critics Say 23 Caesar, King John, King Lear, Love’s Labor’s Lost, Macbeth, Measure Why Teach Macbeth? 34 for Measure, The Merchant of Venice, The Merry Wives of Windsor, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, Othello, Pericles, A Play Comes to Life Richard II, Richard III, Romeo and Juliet, The Taming of the Shrew, A Look Back at Macbeth in Performance 38 The Tempest, Timon of Athens, Troilus and Cressida, Twelfth Night, Dueling Macbeths Erupt in Riots! 42 The Two Gentlemen of Verona, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and The A Conversation with the Director 43 Winter’s Tale. -

Celebrating Shakespeare's Plays

Celebrating Shakespeare’s Plays Over 400 Years of Drama This is an Interactive Book List Click on the cover of each book to read descriptions and reviews on Amazon.com Search for these titles online at the San Diego Public Library, San Diego County Library or on the Libby app to read them for free. The Bard of Avon One of my sixth grade teachers introduced me to Shakespeare’s plays. I can still remember him telling my class that we were going to put on a really fun play called Hamlet. It had ghosts, murder and romance and that we’d get to learn how to sword fight. Putting on Hamlet was every bit as fun as he promised it would be. We all enjoyed it so much that our class put on The Taming of the Shrew during our Summer vacation. I know what you’re thinking. Why on Earth did 12 year old Ms. Furey give up her Summer break to put on a 400 year old play? That’s easy. Ghosts. Murder. Romance. Sword fighting! Shakespeare wrote plays that are amazingly fun to read, watch and perform. I hope this list will inspire you to give the Bard a try. I’m sure you’ll like him as as much as I do. --Ms. Furey Shakespearean Characters Thomas Stothard, painter (1755–1834) Tate Gallery, London, England Shakespeare’s Plays The Oxford The Complete The Complete All's Well That Shakespeare: The Works of Illustrated Ends Well Complete Works, Shakespeare Stratford (Folger 2nd Edition by William Shakespeare Shakespeare by William Shakespeare by William Library) Shakespeare Shakespeare by William Shakespeare Shakespeare’s Plays Antony and As You Like It The Comedy of -

Citing Sources With

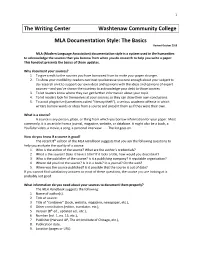

1 The Writing Center Washtenaw Community College MLA Documentation Style: The Basics Revised October 2018 MLA (Modern Language Association) documentation style is a system used in the humanities to acknowledge the sources that you borrow from when you do research to help you write a paper. This handout presents the basics of those updates. Why document your sources? 1. To give credit to the sources you have borrowed from to make your paper stronger. 2. To show your credibility: readers can trust you because you care enough about your subject to do research on it to support our own ideas and opinions with the ideas and opinions of expert sources—and you’ve shown the courtesy to acknowledge your debt to those sources. 3. To let readers know where they can get further information about your topic. 4. To let readers look for themselves at your sources so they can draw their own conclusions. 5. To avoid plagiarism (sometimes called “literary theft”), a serious academic offense in which writers borrow words or ideas from a source and present them as if they were their own. What is a source? A source is any person, place, or thing from which you borrow information for your paper. Most commonly, it is an article from a journal, magazine, website, or database. It might also be a book, a YouTube video, a movie, a song, a personal interview. The list goes on. How do you know if a source is good? The recent 8th edition of the MLA Handbook suggests that you ask the following questions to help you evaluate the quality of a source: 1. -

9781474435949 Shakespeare I

Shakespeare in the North 66713_Hansen.indd713_Hansen.indd i 118/01/218/01/21 22:46:46 PPMM 66713_Hansen.indd713_Hansen.indd iiii 118/01/218/01/21 22:46:46 PPMM Shakespeare in the North Place, Politics and Performance in England and Scotland Edited by Adam Hansen 66713_Hansen.indd713_Hansen.indd iiiiii 118/01/218/01/21 22:46:46 PPMM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matter and organisation Adam Hansen, 2021 © the chapters their several authors, 2021 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road, 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry, Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Bembo by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3592 5 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3594 9 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3595 6 (epub) The right of Adam Hansen to be identifi ed as the editor of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66713_Hansen.indd713_Hansen.indd iivv 118/01/218/01/21 22:46:46 PPMM Contents Acknowledgements vii Notes on Contributors viii Introduction 1 Adam Hansen I: Shakespeare and the Early Modern North 1. -

Review: Crystal, David. 2016. the Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation

REVIEWS Complutense Journal of English Studies ISSN: 2386-3935 http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/CJES.54906 Review: Crystal, David. 2016. The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 648 pp. ISBN: 978-0-19- 966842-7. This impressive and elaborated dictionary, which is the subject of the present review, has been compiled by David Crystal and is comprised of a total of 648 pages in a single volume. The publication of this dictionary by Oxford University Press (OUP) is the culmination of ten years of ongoing research during which time Crystal has written extensive publications on issues dealing with the language of Shakespeare (e.g. Crystal and Crystal 2002, 2005a,1 and 2005b;2 Crystal 2005a, 2008, and 2013). This compilation of material can be appreciated when reading the explanatory sections at the beginning of the book. Moreover, it is not the first time that Crystal has published a dictionary based on the language of the Bard of Avon, where another clear example is the recently published dictionary with illustrations compiled in collaboration with Ben Crystal (see Crystal and Crystal 2015).3 Hence, the present dictionary is framed within the ever-expanding literature concerning studies on the original pronunciation (OP) of (Shakespearean) English, whose findings have just started to come to light during the last few decades (see also other major works dealing with Elizabethan phonology such as Dobson (1957), Cercignani (1981), Barber (1997), Lass (1999), Crystal (2005b), Lass (2006), Nevalainen (2006), McMahon (2012), Baugh and Cable (2013), among many others). Now, Crystal has joined efforts to provide an Early Modern Shakespearean pronunciation reference tool for (a) professional actors and theatre companies (e.g. -

Memory in Shakespeare's Second Tetralogy

TITLE PAGE Memory in Shakespeare’s Second Tetralogy Rebecca Warren-Heys Royal Holloway, University of London Submission for Doctor of Philosophy DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is clearly stated. Rebecca Warren-Heys, October 2013. 2 THESIS ABSTRACT This thesis undertakes an original analysis of the incidence and influence of memory in Shakespeare’s second tetralogy. It is the first full-length study of memory in Shakespeare to show not only how memories can lock characters into history but also how memories can be released from history in order to engender radically different futures. This thesis offers detailed close readings of key scenes in the second tetralogy to substantiate this argument and to illuminate afresh issues at the heart of the plays, such as identity, time and death. It builds on previous and current research on memory in Shakespeare, as well as considering how he may have engaged with original archival sources such as Petrus’s ‘Art of Memory’ and Gratarolo’s ‘Castle of Memory’. The first chapter of this thesis provides an overview of Shakespeare’s use of and reliance on memory in the canon, supplies a review of previous works on memory, and explains the scope and structure of the thesis. The second chapter defines terms and clarifies the method of the thesis, considers the phenomenology of memory, and elucidates the crucial concept of forward recollection. The third chapter explores how and why Shakespeare’s drama is an especially apt vehicle for memory. -

ENGLISH LITERATURE Summer Learning SET TEXTS FOR

ENGLISH LITERATURE Summer Learning SET TEXTS FOR AUTUMN TERM These are the books you need to buy and read before the course begins. Check the ISBN number carefully before you order so that you get the right edition! Remember: these are the two most important books on this summer reading list. So not only will you need to make sure that you have actually read them, you will also need to make sure that you have read them well. According to David Lodge, 'narrative, whatever its medium – words, film, strip cartoon – holds the interest of an audience by raising questions in their minds, and delaying the answers.' You need to be very alert to this on your first reading, as you can never have that first reading again. On any subsequent reading, you will already have a knowledge of the story as a whole, which will inform your reading of any of the parts. So, whenever you close the books below, stop, summarise what you've read, and the questions that these pages you’ve read raise – whether that's about what's going on, who that character that's just been introduced is, what they're referring to, or what you think it might mean for us and how we live our lives today. There is no question too big or too small. Record these questions as they occur to you, in a reading journal, and bring this with you on the first day of term. The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood (1996 edition, Vintage, ISBN: 978-0099740919) There's a reason this is now a 'smash hit TV series'; in fact, there are several. -

Teaching Shakespeare 4 Autumn 2013 3 Variation Between Countries Regarding What Language Are Signs of Change

a magazine FOR ALL SHAKESPEARE EDUCATORS Policy • Pedagogy • Practice Issue 4 Autumn 2013 teaching ISSN 2049-3568 (Print) • ISSN 2049-3576 (Online) Shakespeare SPRING INTO SHAKESPEARE WITH EDITOR AND ACTOR BEN CRYSTAL DIG INTO EDWARD’S BOYS’ HENRY V WITH THEIR DIRECTOR, PERRY MILLS SEE SHAKESPEARE’S DOMINANCE AT A-LEVEL FROM A PGCE PERSPECTIVE DO THE MATHS ON TEACHING SHAKESPEARE GLOBALLY Find this magazine and more online at shakespeareineducation.com NOTICEBOARD EDITORIAL Photo © Oliver Jones P P ‘ eritage’ is the focus of this issue which includes articles © hoto on playing Shakespeare in hoto © Sarah the rSc’s Swan theatre and the king edward School, alsoM known as ‘Shakespeare’s ichelle ichelle school’, by Perry mills; on teaching the works of other early modern authors by O live M HBethanie lord; and questioning whether the notion of heritage isorton a burden or a blessing for teachers and students of Shakespeare by Ben crystal. In this way, issue 4 considers heritage in terms of She writes: not only is it committed to in-spiring practices – educational and theatrical; places, including children through interactive sessions at Mary Arden’s Stratford-upon-Avon as Shakespeare’s hometown; and Farm, Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, Hall’s Croft, Nash’s legacies, by considering his dominance in the classroom House and Shakespeare’s Birthplace, but the campaign as the representative of early modern drama. Articles also invites teachers and pupils to explore many of their by Cathleen McKague and Matt O’Connor argue the 70 cultural partners, including the British Museum, importance of acting or playing Shakespeare with Bosworth Heritage Centre and the Royal Shakespeare students as an antidote to off-putting perceptions of Company. -

Sticks, Sonnets & Verse

Sticks, Sonnets & Verse ~ Actors' Workshop by Ben Crystal presented by SGCNZ in association with Circa Theatre, TACT & the British Council Monday 22 May 2017 9.30-11.30am Venue - Circa Theatre, Wellington Cost: $25 Bookings essential via form below - 14 participants max Enquiries: P: 04 384 1300 M: O27 283 6016 E: [email protected] Exploring the physicality, heart and mechanics of Shakespeare, with an introduction to Original Pronunciation, the accent of the time. A morning with Ben Crystal, actor, producer, and artistic director of the internationally renowned original practices Shakespeare Ensemble, Passion in Practice. Wear loose, comfortable clothing, and be prepared to move. No prep required. BEN CRYSTAL - Guest Speaker UK Actor/writer/Producer, Ben Crystal was the co-writer of Shakespeare’s Words (Penguin 2002) and The Shakespeare Miscellany (Penguin 2005) with his father David Crystal. His first solo book, Shakespeare on Toast – Getting a Taste for the Bard (Icon 2008) was shortlisted for the 2010 Educational Writer of the Year Award. Springboard Shakespeare, a quartet series of introductions for Arden Shakespeare / Bloomsbury - was published June 2013 and An Illustrated Dictionary of Shakespeare was published April 2015 with OUP (writing again with his father). In 2011 he performed the title role in the world contemporary premier of Hamlet in Original Pronunciation, and in 2012 he was the curator and creative director on a CD of Shakespeare in Original Pronunciation for the British Library. He is the artistic director of Passion in Practice and its Shakespeare Ensemble. Together they have performed staged readings of Macbeth, Henry V, and Dr Faustus at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, Shakespeare’s Globe, and produced minimal rehearsal, cue-script rehearsed sold-out limited-runs of these plays in full production at a Wanamaker-like Loft in London.