Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catholics and Jews: and for the Sentiments Expressed

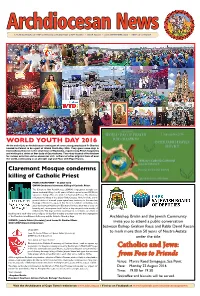

Archdiocesan News A PUBLICATION OF THE CATHOLIC CHURCH OF CAPE TOWN • ISSUE NO 81 • JULY-SEPTEMBER 2016 • FREE OF CHARGE WORLD YOUTH DAY 2016 At the end of July an Archdiocesan contingent of seven young people (and Fr Charles) headed to Poland to be a part of World Youth Day 2016. They spent some days in Czestochowa Diocese in the small town of Radonsko, experiencing Polish hospitality and visiting the shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa. Then they headed off to Krakow for various activities and an encounter with millions of other pilgrims from all over the world, culminating in an all-night vigil and Mass with Pope Francis. Claremont Mosque condemns killing of Catholic Priest PRESS STATEMENT – 26 JULY 2016 CMRM Condemns Inhumane Killing of Catholic Priest The Claremont Main Road Mosque (CMRM) congregation strongly con- demns the brutal killing of an 85 year-old Catholic priest by two ISIS/Da`ish supporters during a Mass at a Church in Normandy, France. The inhumane and gruesome killing of the elderly Father Jacques Hamel and the sacrili- geous violation of a sacred prayer space bears testimony to the merciless ideology of Da`ish. It is apparent that Da`ish is hell-bent on fuelling a reli- gious war between Muslims and Christians. However, their war is a war on humanity and our response should reflect a deep respect for the sanctity of all human life. This tragic incident should spur us to redouble our efforts at reaching out to each other across religious divides. Our thoughts and prayers are with the congregation of the Church in Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray and the Catholic Church at large. -

France 2016 International Religious Freedom Report

FRANCE 2016 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The constitution and the law protect the right of individuals to choose, change, and practice their religion. The government investigated and prosecuted numerous crimes and other actions against religious groups, including anti-Semitic and anti- Muslim violence, hate speech, and vandalism. The government continued to enforce laws prohibiting face coverings in public spaces and government buildings and the wearing of “conspicuous” religious symbols at public schools, which included a ban on headscarves and Sikh turbans. The highest administrative court rejected the city of Villeneuve-Loubet’s ban on “clothes demonstrating an obvious religious affiliation worn by swimmers on public beaches.” The ban was directed at full-body swimming suits worn by some Muslim women. ISIS claimed responsibility for a terrorist attack in Nice during the July 14 French independence day celebration that killed 84 people without regard for their religious belief. President Francois Hollande condemned the attack as an act of radical Islamic terrorism. Prime Minister (PM) Manuel Valls cautioned against scapegoating Muslims or Islam for the attack by a radical extremist group. The government extended a state of emergency until July 2017. The government condemned anti- Semitic, anti-Muslim, and anti-Catholic acts and continued efforts to promote interfaith understanding through public awareness campaigns and by encouraging dialogues in schools, among local officials, police, and citizen groups. Jehovah’s Witnesses reported 19 instances in which authorities interfered with public proselytizing by their community. There were continued reports of attacks against Christians, Jews, and Muslims. The government, as well as Muslim and Jewish groups, reported the number of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim incidents decreased by 59 percent and 58 percent respectively from the previous year to 335 anti-Semitic acts and 189 anti-Muslim acts. -

L'interdisciplinarité Comme Levier De Développement Professionnel

l’Interdisciplinarité comme levier de développement professionnel Pascal Claman To cite this version: Pascal Claman. l’Interdisciplinarité comme levier de développement professionnel. Education. CY Cergy Paris Université, 2020. Français. NNT : 2020CYUN1096. tel-03274900 HAL Id: tel-03274900 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-03274900 Submitted on 30 Jun 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Université de Cergy-Pontoise École doctorale Éducation-Didactiques-Cognition Laboratoire École Mutations Apprentissages – EA4507 THÈSE Pour l'obtention du titre de Docteur en Sciences de l’éducation Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Pascal CLAMAN Le 21 octobre 2020 Sous la direction de Marie-Laure ELALOUF Professeur des universités, CY Cergy Paris Université, Inspé de l’académie de Versailles L’interdisciplinarité comme levier de développement professionnel Cas des professeurs affectés en collège dans l’académie de la Guadeloupe entre 2015 et 2018 Jury : Jean-Pierre Chevalier, Professeur des universités, CY Cergy Paris Université, Inspé de l’académie de Versailles, examinateur Richard Etienne, Professeur des universités, Université de Montpellier, LIRDEF, rapporteur Arnaud Dubois, Professeur des universités, Université de Rouen, Cirnef, rapporteur Stephan Martens, Professeur des universités, CY Cergy Paris Université, Agora, examinateur. -

St. Maria Goretti Catholic Church Twenty-Eighth Sunday in Ordinary Time - October 11, 2020

ST. MARIA GORETTI CATHOLIC CHURCH TWENTY-EIGHTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME - OCTOBER 11, 2020 They Would Not Come to the Feast! (Matthew 22:1-14) My Dear Parishioners, THIS WEEK: OCTOBER 11, 2020 Saints are called even in modern times – young and old, God calls us continuously to live holy lives. I am MASS TIMES - INDOORS pleased to share with you two very recent saints of PUBLIC MASSES have resumed. Online Sign-up the Church, whose path to sainthood was fast registration is required for weekend Masses—posted on our tracked by Pope Francis. Fr. Jacques Hamel, st Website smgcc.net each Wednesday at 1:00 PM. Arrive 20 Europe’s first 21 – century martyr, and Ven. Carlo minutes early to check in. Please keep all conversation to Acutis. They both have fascinating stories - a minimum before and after Mass. Fr. Hamel was martyred at the age of 85, while Carlo succumbed to leukemia at age 15. An octogenarian and a teen, they prove to us Saturday Vigil, 5:00 PM that “age does not matter” when it comes to heeding God’s call. Livestream on Facebook at Fr. Hamel was a French priest who, at age 75, chose not to retire https://www.facebook.com/St.MariaGorettiCatholicChurch2020 but instead resume his work at St. Etienne-du-Rouvray. He was martyred while celebrating Mass on 26 July 2016 under the hands of Sunday, 8:00 AM, 10:00 AM and 12:00 PM two Muslim extremists. He uttered the words “Go, Satan!” seeming to Please remember to register online unmask his assailants. -

ISIS/Daesh and Boko Haram Ewelina Ochab and Kelsey Zorzi REPORT

Effects of Terrorism on Enjoyment of Human Rights: ISIS/Daesh and Boko Haram Ewelina Ochab and Kelsey Zorzi REPORT 23 September 2016 Executive Summary Recent years have witnessed the emergence of powerful terrorist groups, notably, ISIS/Daesh in the Middle East and Boko Haram in West Africa. Despite various steps taken to combat them, the terrorist groups continue unchecked by effective deterrence or punishment. While Boko Haram’s atrocities are being considered by the Office of the Prosecutor to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in a preliminary examination, ISIS/Daesh remains unchallenged by either the UN Security Council or the ICC. The international community’s failure to prosecute ISIS/Daesh may suggest that a new international mechanism is needed. This report focuses on two main terrorist groups, namely, ISIS/Daesh in the Middle East and beyond, and Boko Haram in Nigeria and West Africa. The report presents the scope of the atrocities committed by both terrorist groups and the effect of the atrocities on the enjoyment of human rights in the affected regions, and beyond. The report further outlines the challenges faced by the affected States in responding to the threats posed by terrorism and proposes best practices to go forward. Table of Contents (a) Introduction .............................................................................................................. 3 A. ISIS/Daesh ....................................................................................................................... 3 a) Background ................................................................................................................ -

Florida Catholic

WWW.THEFLORIDACATHOLIC.ORG | July 28- Aug. 10, 2017 | Volume 78, Number 18 ORLANDO DIOCESE PALM BEACH DIOCESE VENICE DIOCESE Diocese Young Catholics Young people welcomes mirror Christ make mission religious orders at retreat in Grenada FRENCH ARCHBISHOP RECALLS: Priest’s martyrdom life-changing event for him JUNNO AROCHO ESTEVES ther Hamel’s death at the hands of Catholic News Service terrorists claiming to be Muslims, his martyrdom instead has drawn The martyrdom of a French the Catholic and Muslim commu- priest killed a year ago while nities in the diocese closer together, Archbishop Lebrun said. celebrating Mass was an event “This tragic event shared by oth- that “has transformed me as a ers has brought me closer to the bishop,” Archbishop Domi- local society in its diverse com- ponents: naturally to the town of nique Lebrun of Rouen said. Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray and Father Jacques Hamel’s life -- then to the other municipalities “simple and exemplary -- questions in the area,” the archbishop said. me as a pastor and shepherd on how “And from now on, I am bound to to consider the life of priests, on the Muslim community and to the what I expect from them in terms of other communities of believers in efficiency. I must tirelessly convert, the territory of my diocese.” to pass from this request for effi- Father Hamel’s martyrdom drew ciency to admiration for their fruit- the attention of Pope Francis who fulness,” the archbishop said in an celebrated a memorial Mass for interview with the Vatican newspa- him Sept. 14, 2016, with Archbishop per, L’Osservatore Romano. -

Cvs Speakers

Marta Machado ACADEMIC BACKGROUND 2004.2005 Master in European Political and Administrative Studies, College of Europe, Bruges, BELGIUM Courses: Justice and Home Affairs, Security and Defence Policy, European Parliament, EU Institutional Law 1998-2003 Five-Year Law degree, Faculty of Law, University of Lisbon, Portugal Courses: Administrative Law, Civil Law, EC Law, Judicial remedies in European Law 2001-2002 Erasmus Programme, “Universität Bayreuth”, Bayreuth, Germany PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Current position Public Affairs Manager at HOTREC, European Association of Hotels, Restaurants and Cafés, Brussels, Belgium (Since October 2011) • Public policy & legal analysis • Campaign deployment • Stakeholder relationship • Coalition-building • EU consultations • Communication strategy • EU funding monitoring • Project management • Event organisation Main policies and sectors of expertise: EU Institutional Law, Social Affairs, Travel & Tourism, Visa Policy, Data Protection, Health, Migration, Asylum. 2008 Project Manager/Generalist Writer at Intrasoft International/ EURESIN, Private Consultancy working for the European Commission (COM), Brussels, Belgium 2008 Assistant to the Programme Manager at ICMC Europe – International Catholic Migration Commission, NGO, Brussels, Belgium. 2007 Assistant at the Permanent Representation of Portugal to the European Union (PT Perm Rep), Justice and Home Affairs department, before and during the Portuguese Presidency at the Council of the European Union, Brussels, Belgium. 2006 Assistant at the European Parliament, -

Bulletin 78-79

bulletin 78-79 International Sociological Association Association Internationale de Sociologie Asociación Internacional de Sociología Faculty of Political Sciences and Sociology University Complutense 28223 Madrid, Spain. Tel: (34)91352 76 50 Fax: (34)913524945. Email: [email protected] http://www.ucm.es/info/isa D "Research Committees and International Sociological Association" by Arnaud Sales, Vice-President for Research, with an introduction by Alberto Martinelli, President 1 D Reports from the Research Committees, Working and Thematic Groups 7 D In Memoriam: Niklas Luhmann (1927-1998) 24 D Publications of the ISA Books Reviews section of International Sociology by Jennifer Platt 26 Announcing New Editor of the Sage Studies in International Sociology 26 D Short Report from XIV World Congress of Sociology by Gilles Pronovost, CLOC 27 D Calendar of Future Events 28 D 1999 Coupon Listing Sprfng 1999 Published by the Intemational Sociological Association ISSN0383-8501 Editor: lzabela Barllnska. Lay-out: José 1. Reguera. Printed by Fotocopias Universidad S.A. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Fa 111998 - Summer 2002 Presldent: Jan Marie FRITZ Publlcatlons Commlttee Alberto MARTINELLI University of Cincinnati Chair: Christine Inglis University of Milano Cincinnati, USA EC representatives: Bernadette Milano, Italy Bawin-Legros, Roberto Briceño- Jorge GONZÁLEZ SÁNCHEZ Leon Universidad de Colima RCC representative: Peter Vlce-Presldent, Research Colima, Mexico Weingart Current Sociology : Susan Arnaud SALES McDaniel (Editor),2 Université de Montréal Bert KLANDERMANS -

Facing the Future 16 Journalism Journalists 18 Joining Cinema Giants in Storytelling 24 Radio La Radio Au Centre Eyecatcher Du Congrès

SIGNIS MEDIA N°3/2017 Publication trimestrielle multilingue / Multilingual quarterly magazine / Revista trimestral multilingüe Facing Samuel Tessier Samuel © ISSN 0771-0461 - Publication trimestrielle - Bureau de Poste Bruxelles X - Octobre 2017 X - Octobre Bruxelles de Poste trimestrielle - Bureau ISSN 0771-0461 - Publication the Future Contents 4 Cover Story Facing the Future 16 Journalism Journalists 18 joining Cinema Giants in Storytelling 24 Radio La radio au centre Eyecatcher du Congrès El centenario del nacimiento de Monseñor Oscar Romero, Patrono de SIGNIS Hace cien años nació Oscar Romero, el 15 de agosto de 1917 en El Salvador. Como Obispo de la Diócesis de Santiago de María (1974-1977) “comenzó a ver de cerca la realidad de pobreza y miseria en que vivían la mayor parte de campesinos”. En 1977 fue nombrado Arzobispo de San Salvador en medio de un ambiente de injusticias, represión e incertidumbre. Creó una oficina de Derechos Humanos y abrió las puertas de la Iglesia para dar refugio a los oprimidos. En esos años Moseñor Romero cuestionaba el por qué los medios de comunicación estaban en manos de los poderosos: era su voz que se oía y, a través de la televisión, eran sus imágenes las que se veían. Y si las imágenes de los oprimidos eran difundidas por estos medios, era para criminalizarlos y deshumanizarlos. Dedicó especial atención a su forma de comunicación más directa: sus homilías dominicales en la Catedral, tomando también en consideración los aportes de las muchas cartas y visitantes que recibía. Las homilías eran transmitidas por la estación de radio de la Arquidiócesis: YSAX, y alcanzaban todos los rincones del país con sus denuncias contra la violencia de las fuerzas militares del gobierno y de los grupos armados de izquierda. -

Unfashionable Objections to Islamophobic Cartoons

Unfashionable Objections to Islamophobic Cartoons Unfashionable Objections to Islamophobic Cartoons: L’Affaire Charlie Hebdo By Dustin J. Byrd Unfashionable Objections to Islamophobic Cartoons: L’Affaire Charlie Hebdo By Dustin J. Byrd This book first published 2017 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2017 by Dustin J. Byrd All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9124-X ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9124-0 For Jamie, my foundation stone Fluctuat nec Mergitur ~ Motto of Paris Allah will not be merciful to those who are not merciful to people. ~ Prophet Muhammad It's normal – you cannot provoke; you cannot insult the faith of others. ~ Pope Francis I believe in the brotherhood of all men, but I don't believe in wasting brotherhood on anyone who doesn't want to practice it with me. Brotherhood is a two-way street. ~ Malcolm X What is dangerous about the creeping villainy is that is takes considerable imagination and considerable dialectical abilities to be able to detect it at the moment and see what it is. Well, neither of these features are prominent in most people – and so the villainy creeps forward just a little bit each day, unnoticed. ~ Søren Kierkegaard Our responsibility is much greater than we might have supposed, because it involves all mankind. -

Pope: Answering God's Call Demands Courage to Take a Risk

LENT: CARDINAL HOLY FACE: Talk to God and LEVADA: Venerating he will answer, Comment on Pope Jesus’ reputed students told Francis’ summit crucifixion veil PAGE 3 PAGE 18 PAGE 24 CATHOLIC SAN FRANCISCO Newspaper of the Archdiocese of San Francisco www.catholic-sf.org SERVING SAN FRANCISCO, MARIN & SAN MATEO COUNTIES MARCH 14, 2019 $1.00 | VOL. 21 NO. 5 Pope: Answering God’s call demands courage to take a risk CAROL GLATZ CATHOLIC NEWS SERVICE VATICAN CITY – Answering the Lord’s call de- mands the courage to take a risk, but it is an invita- tion to become part of an important mission, Pope Francis said. God “wants us to discover that each of us is called – in a variety of ways – to something grand, and that our lives should not grow entangled in the nets of an ennui that dulls the heart,” the pope said. “Every vocation is a summons not to stand on the shore, nets in hand, but to follow Jesus on the path he has marked out for us, for our own happiness and for the good of those around us,” he said in his mes- sage for the 2019 World Day of Prayer for Vocations. (PHOTO BY NICHOLAS WOLFRAM SMITH/CATHOLIC SAN FRANCISCO) The Vatican released the pope’s message March 9. The day, which was to be celebrated May 12, was dedicated to the theme: “The courage to take a risk Heart to hearts for God’s promise.” Several hundred people gathered at a eucharistic Holy Hour at St. Pius Church in Redwood City Feb. -

Post-Charlie: Community, Representation, and Terrorism’S Foreclosures

1 H-France Salon Volume 9 (2017), Issue 1, #1 Post-Charlie: Community, Representation, and Terrorism’s Foreclosures Michael O’Riley The Colorado College On 14 July 2016 Mohamed Lahouaiej Bouhlel, a thirty-one-year-old delivery-truck driver raised in northeast Tunisia who held a French residence permit, drove a nineteen-ton refrigeration truck into a crowd gathered to watch fireworks on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice. Bouhlel killed eighty-four people and injured over 300 others. According to French Interior Minister, Bernard Cazeneuve, Bouhlel was a recent, but fervent, ISIS disciple. The Islamic State subsequently claimed responsibility for the massacre. Nearly two weeks later, the Nice attack was followed by another in Saint-Etienne-du-Rouvray where a priest, Jacques Hamel, was killed in church while saying mass. Like the Nice attack, the Saint-Etienne-du Rouvray attack was also claimed by the Islamic State; it was carried out by two nineteen-year-old men, Adel Kermiche, a resident of Saint- Etienne-du-Rouvray, and Abdel-Malik Nabil Petitjean from Aix-les-Bains. Immediately following the Bastille Day attack, President Hollande announced he would seek to extend the state of emergency that had been declared following the Paris attacks in November for another three months. Although that declaration was due to be lifted on 26 July, the French government instead extended the state of emergency for another six months while expanding already broadened police powers of search, detention, surveillance, and identity checks. It would seem that