Arxiv:1402.4957V3 [Math.HO] 12 Sep 2014 .INTRODUCTION I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuous Nowhere Differentiable Functions

2003:320 CIV MASTER’S THESIS Continuous Nowhere Differentiable Functions JOHAN THIM MASTER OF SCIENCE PROGRAMME Department of Mathematics 2003:320 CIV • ISSN: 1402 - 1617 • ISRN: LTU - EX - - 03/320 - - SE Continuous Nowhere Differentiable Functions Johan Thim December 2003 Master Thesis Supervisor: Lech Maligranda Department of Mathematics Abstract In the early nineteenth century, most mathematicians believed that a contin- uous function has derivative at a significant set of points. A. M. Amp`ereeven tried to give a theoretical justification for this (within the limitations of the definitions of his time) in his paper from 1806. In a presentation before the Berlin Academy on July 18, 1872 Karl Weierstrass shocked the mathematical community by proving this conjecture to be false. He presented a function which was continuous everywhere but differentiable nowhere. The function in question was defined by ∞ X W (x) = ak cos(bkπx), k=0 where a is a real number with 0 < a < 1, b is an odd integer and ab > 1+3π/2. This example was first published by du Bois-Reymond in 1875. Weierstrass also mentioned Riemann, who apparently had used a similar construction (which was unpublished) in his own lectures as early as 1861. However, neither Weierstrass’ nor Riemann’s function was the first such construction. The earliest known example is due to Czech mathematician Bernard Bolzano, who in the years around 1830 (published in 1922 after being discovered a few years earlier) exhibited a continuous function which was nowhere differen- tiable. Around 1860, the Swiss mathematician Charles Cell´erieralso discov- ered (independently) an example which unfortunately wasn’t published until 1890 (posthumously). -

On the Origin and Early History of Functional Analysis

U.U.D.M. Project Report 2008:1 On the origin and early history of functional analysis Jens Lindström Examensarbete i matematik, 30 hp Handledare och examinator: Sten Kaijser Januari 2008 Department of Mathematics Uppsala University Abstract In this report we will study the origins and history of functional analysis up until 1918. We begin by studying ordinary and partial differential equations in the 18th and 19th century to see why there was a need to develop the concepts of functions and limits. We will see how a general theory of infinite systems of equations and determinants by Helge von Koch were used in Ivar Fredholm’s 1900 paper on the integral equation b Z ϕ(s) = f(s) + λ K(s, t)f(t)dt (1) a which resulted in a vast study of integral equations. One of the most enthusiastic followers of Fredholm and integral equation theory was David Hilbert, and we will see how he further developed the theory of integral equations and spectral theory. The concept introduced by Fredholm to study sets of transformations, or operators, made Maurice Fr´echet realize that the focus should be shifted from particular objects to sets of objects and the algebraic properties of these sets. This led him to introduce abstract spaces and we will see how he introduced the axioms that defines them. Finally, we will investigate how the Lebesgue theory of integration were used by Frigyes Riesz who was able to connect all theory of Fredholm, Fr´echet and Lebesgue to form a general theory, and a new discipline of mathematics, now known as functional analysis. -

![Arxiv:2106.01162V1 [Math.HO] 27 May 2021 Shine Conference in Kashiwa” 1 and Contain a Number of New Perspectives and Ob- Servations on Monstrous Moonshine](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0845/arxiv-2106-01162v1-math-ho-27-may-2021-shine-conference-in-kashiwa-1-and-contain-a-number-of-new-perspectives-and-ob-servations-on-monstrous-moonshine-950845.webp)

Arxiv:2106.01162V1 [Math.HO] 27 May 2021 Shine Conference in Kashiwa” 1 and Contain a Number of New Perspectives and Ob- Servations on Monstrous Moonshine

Kashiwa Lectures on New Approaches to the Monster John McKay1 edited and annotated by Yang-Hui He2;3;4;5 1 CICMA & Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Concordia University, 1455 de Maisonneuve Blvd. West, Montreal, Quebec, H3G 1M8, Canada 2 London Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Royal Institution of Great Britain, 21 Albemarle Street, Mayfair, London W1S 4BS, UK; 3 Merton College, University of Oxford, OX14JD, UK; 4 Department of Mathematics, City, University of London, EC1V 0HB, UK; 5 School of Physics, NanKai University, Tianjin, 300071, P.R. China [email protected] [email protected] Abstract These notes stem from lectures given by the first author (JM) at the 2008 \Moon- arXiv:2106.01162v1 [math.HO] 27 May 2021 shine Conference in Kashiwa" 1 and contain a number of new perspectives and ob- servations on Monstrous Moonshine. Because many new points have not appeared anywhere in print, it is thought expedient to update, annotate and clarify them (as footnotes), an editorial task which the second author (YHH) is more than delighted to undertake. We hope the various puzzles and correspondences, delivered in a personal and casual manner, will serve as diversions intriguing to the community. 1Organized by the Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (IPMU) under the support of the Graduate School of Mathematical Sciences, the University of Tokyo. 1 Contents 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Resources . 3 1.2 Talk Outline . 5 1.3 Where to Start ? . 6 2 Monstrous Moonshine 9 2.1 Primes in the Monster's Order . 10 2.2 Balance . -

Fundamental Theorems in Mathematics

SOME FUNDAMENTAL THEOREMS IN MATHEMATICS OLIVER KNILL Abstract. An expository hitchhikers guide to some theorems in mathematics. Criteria for the current list of 243 theorems are whether the result can be formulated elegantly, whether it is beautiful or useful and whether it could serve as a guide [6] without leading to panic. The order is not a ranking but ordered along a time-line when things were writ- ten down. Since [556] stated “a mathematical theorem only becomes beautiful if presented as a crown jewel within a context" we try sometimes to give some context. Of course, any such list of theorems is a matter of personal preferences, taste and limitations. The num- ber of theorems is arbitrary, the initial obvious goal was 42 but that number got eventually surpassed as it is hard to stop, once started. As a compensation, there are 42 “tweetable" theorems with included proofs. More comments on the choice of the theorems is included in an epilogue. For literature on general mathematics, see [193, 189, 29, 235, 254, 619, 412, 138], for history [217, 625, 376, 73, 46, 208, 379, 365, 690, 113, 618, 79, 259, 341], for popular, beautiful or elegant things [12, 529, 201, 182, 17, 672, 673, 44, 204, 190, 245, 446, 616, 303, 201, 2, 127, 146, 128, 502, 261, 172]. For comprehensive overviews in large parts of math- ematics, [74, 165, 166, 51, 593] or predictions on developments [47]. For reflections about mathematics in general [145, 455, 45, 306, 439, 99, 561]. Encyclopedic source examples are [188, 705, 670, 102, 192, 152, 221, 191, 111, 635]. -

Quaternions: a History of Complex Noncommutative Rotation Groups in Theoretical Physics

QUATERNIONS: A HISTORY OF COMPLEX NONCOMMUTATIVE ROTATION GROUPS IN THEORETICAL PHYSICS by Johannes C. Familton A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D Columbia University 2015 Approved by ______________________________________________________________________ Chairperson of Supervisory Committee _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________ Program Authorized to Offer Degree ___________________________________________________________________ Date _______________________________________________________________________________ COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY QUATERNIONS: A HISTORY OF COMPLEX NONCOMMUTATIVE ROTATION GROUPS IN THEORETICAL PHYSICS By Johannes C. Familton Chairperson of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Bruce Vogeli and Dr Henry O. Pollak Department of Mathematics Education TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures......................................................................................................iv List of Tables .......................................................................................................vi Acknowledgements .......................................................................................... vii Chapter I: Introduction ......................................................................................... 1 A. Need for Study ........................................................................................ -

Rudi Mathematici

Rudi Mathematici x4-8188x3+25139294x2-34301407052x+17549638999785=0 Rudi Mathematici January 53 1 S (1803) Guglielmo LIBRI Carucci dalla Sommaja Putnam 1999 - A1 (1878) Agner Krarup ERLANG (1894) Satyendranath BOSE Find polynomials f(x), g(x), and h(x) _, if they exist, (1912) Boris GNEDENKO such that for all x 2 S (1822) Rudolf Julius Emmanuel CLAUSIUS f (x) − g(x) + h(x) = (1905) Lev Genrichovich SHNIRELMAN (1938) Anatoly SAMOILENKO −1 if x < −1 1 3 M (1917) Yuri Alexeievich MITROPOLSHY 4 T (1643) Isaac NEWTON = 3x + 2 if −1 ≤ x ≤ 0 5 W (1838) Marie Ennemond Camille JORDAN − + > (1871) Federigo ENRIQUES 2x 2 if x 0 (1871) Gino FANO (1807) Jozeph Mitza PETZVAL 6 T Publish or Perish (1841) Rudolf STURM "Gustatory responses of pigs to various natural (1871) Felix Edouard Justin Emile BOREL 7 F (1907) Raymond Edward Alan Christopher PALEY and artificial compounds known to be sweet in (1888) Richard COURANT man," D. Glaser, M. Wanner, J.M. Tinti, and 8 S (1924) Paul Moritz COHN C. Nofre, Food Chemistry, vol. 68, no. 4, (1942) Stephen William HAWKING January 10, 2000, pp. 375-85. (1864) Vladimir Adreievich STELKOV 9 S Murphy's Laws of Math 2 10 M (1875) Issai SCHUR (1905) Ruth MOUFANG When you solve a problem, it always helps to (1545) Guidobaldo DEL MONTE 11 T know the answer. (1707) Vincenzo RICCATI (1734) Achille Pierre Dionis DU SEJOUR The latest authors, like the most ancient, strove to subordinate the phenomena of nature to the laws of (1906) Kurt August HIRSCH 12 W mathematics. -

Rudi Mathematici

Rudi Mathematici 4 3 2 x -8176x +25065656x -34150792256x+17446960811280=0 Rudi Mathematici January 1 1 M (1803) Guglielmo LIBRI Carucci dalla Somaja (1878) Agner Krarup ERLANG (1894) Satyendranath BOSE 18º USAMO (1989) - 5 (1912) Boris GNEDENKO 2 M (1822) Rudolf Julius Emmanuel CLAUSIUS Let u and v real numbers such that: (1905) Lev Genrichovich SHNIRELMAN (1938) Anatoly SAMOILENKO 8 i 9 3 G (1917) Yuri Alexeievich MITROPOLSHY u +10 ∗u = (1643) Isaac NEWTON i=1 4 V 5 S (1838) Marie Ennemond Camille JORDAN 10 (1871) Federigo ENRIQUES = vi +10 ∗ v11 = 8 (1871) Gino FANO = 6 D (1807) Jozeph Mitza PETZVAL i 1 (1841) Rudolf STURM Determine -with proof- which of the two numbers 2 7 M (1871) Felix Edouard Justin Emile BOREL (1907) Raymond Edward Alan Christopher PALEY -u or v- is larger (1888) Richard COURANT 8 T There are only two types of people in the world: (1924) Paul Moritz COHN (1942) Stephen William HAWKING those that don't do math and those that take care of them. 9 W (1864) Vladimir Adreievich STELKOV 10 T (1875) Issai SCHUR (1905) Ruth MOUFANG A mathematician confided 11 F (1545) Guidobaldo DEL MONTE That a Moebius strip is one-sided (1707) Vincenzo RICCATI You' get quite a laugh (1734) Achille Pierre Dionis DU SEJOUR If you cut it in half, 12 S (1906) Kurt August HIRSCH For it stay in one piece when divided. 13 S (1864) Wilhelm Karl Werner Otto Fritz Franz WIEN (1876) Luther Pfahler EISENHART (1876) Erhard SCHMIDT A mathematician's reputation rests on the number 3 14 M (1902) Alfred TARSKI of bad proofs he has given. -

~2 Q ! / Date an EXPOSITION on the KRONECKER-WEBER THEOREM

An exposition on the Kronecker-Weber theorem Item Type Thesis Authors Baggett, Jason A. Download date 24/09/2021 09:05:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/11349 AN EXPOSITION ON THE KRONECKER-WEBER THEOREM By Jason A. Baggett RECOMMENDED: Advisory Committee Chair Chair, Department of Mathematics APPROVED: Dean, College of Natural §sztfmce and Mathematics ; < r Dean of the Graduate School ~2 Q_! / Date AN EXPOSITION ON THE KRONECKER-WEBER THEOREM A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Jason A. Baggett, B.S. Fairbanks, Alaska May 2011 iii Abstract The Kronecker-Weber Theorem is a classification result from Algebraic Number Theory. Theorem (Kronecker-Weber). Every finite, abelian extension Qof is contained in a cyclo- tomic field. This result was originally proven by Leopold Kronecker in 1853. However, his proof had some gaps that were later filled by Heinrich Martin Weber in 1886 and David Hilbert in 1896. Hilbert's strategy for the proof eventually led to the creation of the field of mathematics called Class Field Theory, which is the study of finite, abelian extensions of arbitrary fields and is still an area of active research. Not only is the Kronecker-Weber Theorem surprising, its proof is truly amazing. The idea of the proof is that for a finite, Galois extension K of Q, there is a connection be tween the Galois group Gal(K/Q) and how primes of Z split in a certain subring R of K corresponding to Z in Q. -

Beyond Infinity: Georg Cantor and Leopold Kronecker's Dispute Over

Beyond Infinity: Georg Cantor and Leopold Kronecker's Dispute over Transfinite Numbers Author: Patrick Hatfield Carey Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/481 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2005 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College College of Arts and Sciences (Honors Program) Philosophy Department Advisor: Professor Patrick Byrne BEYOND INFINITY : Georg Cantor and Leopold Kronecker’s Dispute over Transfinite Numbers A Senior Honors Thesis by PATRICK CAREY May, 2005 Carey 2 Preface In the past four years , I have devoted a significant amount of time to the study of mathematics and philosophy. Since I was quite young, toying with mathematical abstractions interested me greatly , and , after I was introduced to the abstract realities of philosophy four years ago, I could not avoid pursuing it as well. As my interest in these abstract fields strengthened, I noticed myself focusing on the ‘big picture. ’ However, it was not until this past year that I discovered the natural apex of my studies. While reading a book on David Hilbert 1, I found myself fascinated with one facet of Hi lbert’s life and works in particular: his interest and admiration for the concept of ‘actual’ infinit y developed by Georg Cantor. After all, what ‘big ger picture’ is there than infinity? From there, and on the strong encouragement of my thesis advisor—Professor Patrick Byrne of the philosophy department at Boston College —the topic of my thesis formed naturally . The combination of my interest in the in finite and desire to write a philosophy thesis with a mathemati cal tilt led me inevitably to the incredibly significant philosophical dispute between two men with distinct views on the role of infinity in mathematics: Georg Cantor and Leopold Kronecker. -

Takagi's Class Field Theory

RIMS Kôkyûroku Bessatsu B25 (2011), 125160 Takagis Class Field Theory ‐ From where? and to where? ‐ By * Katsuya MIYAKE §1. Introduction After the publication of his doctoral thesis [T‐1903] in 1903, Teiji Takagi (1875‐ 1960) had not published any academic papers until1914 when World War I started. In the year he began his own investigation on class field theory. The reason was to stay in the front line of mathematics still after the cessation of scientific exchange between Japan and Europe owing to World War I; see [T‐1942, Appendix I Reminiscences and Perspectives, pp.195196] or the quotation below from the English translation [T‐1973, p.360] by Iyanaga. The last important scientific message he received at the time from Europe should be Fueters paper [Fu‐1914] which contained a remarkable result on Kroneckers Ju‐ gendtraum (Kroneckers dream in his young days): Kroneckers Jugendtraum The roots of an Abelian equation over an imagi‐ nary quadratic field k are contained in an extension field of k generated by the singular moduli of elliptic functions with complex multiplication in k and values of such elliptic functions at division points of their periods. (See Subsections 3.2 and 3.3 in Section 3.) K. Fueter treated Abelian extensions of k of odd degrees. Theorem 1.1 (Fueter). Every abelian extension of an imaginary quadratic num‐ ber field k with an odd degree is contained in an extension of k generated by suitable roots of unity and the singular moduli of elliptic functions with complex multiplication in k. Received March 31, 2010. Revised in final form February 17, 2011. -

The Mamas & the Papas of the Math X-Files & Episodic Epitomizing Epithets & a Bit More #77 of Gottschalk's Gestalt

The Mamas & The Papas of The Math X-Files & Episodic Epitomizing Epithets & A Bit More #77 of Gottschalk’s Gestalts A Series Illustrating Innovative Forms of the Organization & Exposition of Mathematics by Walter Gottschalk Infinite Vistas Press PVD RI 2002 GG77-1 (38) „ 2002 Walter Gottschalk 500 Angell St #414 Providence RI 02906 permission is granted without charge to reproduce & distribute this item at cost for educational purposes; attribution requested; no warranty of infallibility is posited GG77-2 • the mother of abstract algebra Amalie ‘Emmy’ Noether 1882 - 1935 German - American • the father of accounting • the father of double-entry bookkeeping • the first mathematician of whom there exists an authentic portrait Luca Pacioli 1445-1514 Italian • the father of acoustics Marin Mersenne 1588 - 1648 French GG77-3 • the father of algebra Diophantus of Alexandria 200? - 284? CE Greek or Abu Ja’far Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi ca 780 - ca 850 CE Persian, born in Baghdad or François Viète 1540 - 1603 French • the father of algebraic invariant theory • the father of matrix algebra • the father of octonions Arthur Cayley 1821 - 1895 English • the king of algebraic invariant theory Paul Albert Gordan 1837 - 1912 German GG77-4 • the father of algebraic topology • the father of dynamical systems • the father of the theory of analytic functions of several complex variables • the greatest French mathematician in the second half of the nineteenth century Jules Henri Poincaré 1854 - 1912 French • the father of American mathematics Eliakim Hastings -

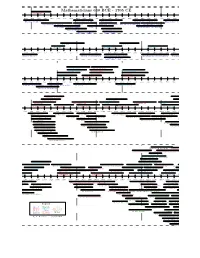

Mathematicians Timeline

Rikitar¯oFujisawa Otto Hesse Kunihiko Kodaira Friedrich Shottky Viktor Bunyakovsky Pavel Aleksandrov Hermann Schwarz Mikhail Ostrogradsky Alexey Krylov Heinrich Martin Weber Nikolai Lobachevsky David Hilbert Paul Bachmann Felix Klein Rudolf Lipschitz Gottlob Frege G Perelman Elwin Bruno Christoffel Max Noether Sergei Novikov Heinrich Eduard Heine Paul Bernays Richard Dedekind Yuri Manin Carl Borchardt Ivan Lappo-Danilevskii Georg F B Riemann Emmy Noether Vladimir Arnold Sergey Bernstein Gotthold Eisenstein Edmund Landau Issai Schur Leoplod Kronecker Paul Halmos Hermann Minkowski Hermann von Helmholtz Paul Erd}os Rikitar¯oFujisawa Otto Hesse Kunihiko Kodaira Vladimir Steklov Karl Weierstrass Kurt G¨odel Friedrich Shottky Viktor Bunyakovsky Pavel Aleksandrov Andrei Markov Ernst Eduard Kummer Alexander Grothendieck Hermann Schwarz Mikhail Ostrogradsky Alexey Krylov Sofia Kovalevskya Andrey Kolmogorov Moritz Stern Friedrich Hirzebruch Heinrich Martin Weber Nikolai Lobachevsky David Hilbert Georg Cantor Carl Goldschmidt Ferdinand von Lindemann Paul Bachmann Felix Klein Pafnuti Chebyshev Oscar Zariski Carl Gustav Jacobi F Georg Frobenius Peter Lax Rudolf Lipschitz Gottlob Frege G Perelman Solomon Lefschetz Julius Pl¨ucker Hermann Weyl Elwin Bruno Christoffel Max Noether Sergei Novikov Karl von Staudt Eugene Wigner Martin Ohm Emil Artin Heinrich Eduard Heine Paul Bernays Richard Dedekind Yuri Manin 1820 1840 1860 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 Carl Borchardt Ivan Lappo-Danilevskii Georg F B Riemann Emmy Noether Vladimir Arnold August Ferdinand