Large Print Guide General History Ordsall Hall Has Had a Varied and Interesting History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volunteering for Wellbeing Final Report 2013 – 2016 Social Return

Inspiring Futures: Volunteering for Wellbeing Final Report 2013 – 2016 Social Return on Investment A Heritage Lottery Fund Project delivered by IWM North and Manchester Museum 2013 - 2016 In partnership with Museum of Science and Industry, People’s History Museum, National Trust: Dunham Massey, Manchester City Galleries, Ordsall Hall, Manchester Jewish Museum, Whitworth Art Gallery, National Football Museum If | Volunteering for Wellbeing | About IWM North and Manchester Museum IWM North IWM North has established itself as a key cultural player in the North. The museum is a learning experience where imaginative exhibitions, programmes and projects are combined to promote public understanding of the causes, course and consequence of war and conflict involving the UK and Commonwealth since 1900. Manchester Museum Manchester Museum is dedicated to inspiring visitors of all ages to learn about the natural world and human cultures, past and present. Tracing its roots as far back as 1821, the museum has grown to become one of the UK’s great regional museums and its largest university museum. Inspiring Futures: Volunteering for Wellbeing Final Report 2013 – 2016 Social Return on Investment If | Volunteering for Wellbeing | Final Report 2013 – 2016 | Social Return on Investment CONTENTSContents About IWM North and Manchester Museum 03 Introduction by lead partners 05 Executive Summary 06 The Report Section 1 | Evaluation, aims and objectives 11 Section 2 | How if works - process inputs 16 Section 3 | What was achieved - Longitudinal outcomes 23 -

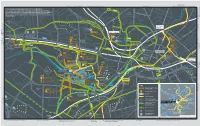

Getting to Salford Quays Map V15 December 2015

Trams to Bury, Ú Ú Ú Ú Ú Ú Bolton Trains to Wigan Trains to Bolton and Preston Prestwich Oldham and Rochdale Rochdale Rochdale to Trains B U R © Crown copyright and database rights 2014 Ordnance Survey 0100022610. B Y R T Use of this data is subject to terms and conditions: You are granted a non-exclusive, royalty O NCN6 E A LL E D E and Leeds free, revocable licence solely to view the Licensed Data for non-commercial purposes for the R W D M T S O D N A period during which Transport for Greater Manchester makes it available; you are not permitted R S T R Lower E O R C BRO to copy, sub-license, distribute, sell or otherwise make available the Licensed Data to third E D UG W R E A HT T O Broughton ON S R LA parties in any form; and third party rights to enforce the terms of this licence shall be reserved NE E L to Ordnance Survey W L L R I O A O H D L N R A D C C D Ú N A A K O O IC M S T R R T A T H E EC G D A H E U E CL ROAD ES LD O R E T R O R F E B R Ellesmere BR E O G A H R D C Park O D G A Pendleton A O R E D R S River A Ú T Ir Oldham Buile Hill Park R wel T E W E l E D L D T Manchester A OL E U NE LES A D LA ECC C H E S I Victoria G T T E C ED Salford O E Peel Park E B S R F L E L L R A T A S A Shopping H T C S T K N F O R G Centre K I T A D W IL R Victoria A NCN55 T Salford Crescent S S O O R J2 Y M R A M602 to M60/M61/M62/M6 bus connections to bus connections to Ú I W L Salford Royal T L L L R E Salford Quays (for MediaCityUK) H Salford Quays (for MediaCityUK) R A A O Hospital T S M Seedley Y A N N T A E D T H E A E E D S L L R -

07 Art on the Edge

Creativetourist.com is a monthly online magazine and series of city guides that have been put together 01 INTRODUCTION by Manchester Museums Consortium. This group of nine museums and galleries in Manchester are separate 02 SMALL WONDERS venues that share a dual vision: the desire to stage intelligent, thought- provoking and outward looking 03 ANIMAL MAGIC exhibitions and events; and to celebrate the city in which they live, work and play. Twice a year, Creativetourist. 04 RUN OF THE MILL com publishes insider guides to the city – uncovering not just galleries and museums but shops, bars, leftfield 05 GENE GENIUS events, restaurants and nights out that are distinctly, uniquely Mancunian. This guide has been developed in 06 SUMMER SPECIALS association with World Class Service. ON THE HOOF 07 ART ON THE EDGE 08 RAIN OR SHINE 09 FiELD TRIPS 10 TOP FIVES 11 FOR BABIES (AND THEIR PARENTS) 12 FOR TODDLERS 13 STUFF FOR KIDS 14 UNDER 18s ONLY 15 BOOK YOUR STAY This project would not be possible without the support of: It’S SUMMERTIME IN MANCHESTER, AND there’S LOTS TO DO. FROM AL FRESCO FILM TO MUSICAL SHIPPING CONTAINERS, FROM A NEW LiVING WORLDS GALLERY TO A CELEBRATION OF FROGS, FROM TALES OF INDUSTRIAL LIFE TO BUILDING YOUR OWN STRAND OF DNA: THIS IS YOUR INDISPENSABLE GUIDE TO THE MUSEUMS AND GALLERIES, THE PARKS AND GARDENS, THE KID- FRIENDLY CAFÉS, SHOPS AND 01 HOTELS OF MANCHESTER. You wouldn’t know it from the most innovative and exciting work 9 must be accompanied by an adult, reading the broadsheets, but the most they can do. -

Familiarisation Guide How to Get to the Hall?

Familiarisation Guide How to get to the Hall? If you are walking to the Hall, please see map of the area We are on Ordsall Lane in Salford, which can be accessed either from Trafford Road and the large roundabout by Old Trafford or from Regent Road and Oldfield Road near the Retail Park, Campanile Hotel and McDonalds. Opposite the Hall is The Foundry and The Soapworks office complexes with the River Irwell pathway taking you to the back entrance of the Foundry for access. How to get to the Hall? You can get the Metrolink MediaCityUK Tram to Exchange Nearby buildings on our street Quay ,then turn right to walk to the Hall, along Ordsall Lane. Walk past the Soapworks on your right and past a small park on your left. Opposite The Foundry you will see our fencing and main gates, which are painted black Enter the site by going through our main gate entrance You can also drive to the Museum POSTCODE M5 3AN. The site has a pay and display car park with 48 spaces. What will I see first? If you have walked or driven along Ordsall Lane, you will enter the site using our main front entrance which is a cobbled road leading to our car park. This is the back of the building with the lawn. There are 2 pedestrian gates, if walking on foot and 1 car entrance if you have come by car or coach trip. These are open between 10am-4pm Mon-Thurs and Sunday 1pm-4pm. Your coach, bus or car will park up and then you need to walk calmly towards to entrance of the museum which is on the other side of the building. -

Manchester FREE

Edition 58 • July/Aug 2016 @FamiliesManch The local magazine for families with children 0-12 years facebook.com/familiesmanchester FREE www.familiesonline.co.uk ® MANCHESTER In this issue > School’s out! Local holiday camps and loads of things to do > School’s back! Ease the transfer to secondary school Covering: Altrincham, Trafford, Salford, Manchester, Bolton, Bury, Rochdale, Didsbury, Stockport, Cheadle, Bramhall, and surrounding areas. Welcome News In this issue Chester Zoo’s newest attractions Summer Reading Challenge 2016 02: News Dinosaurs! The Next Adventure is now 04: Education open at Chester Zoo until Friday 2 The Big Friendly Read will feature 07: Holiday Camps September, and is free with normal zoo some of Roald Dahl’s best-loved 10: Parents’ place admission. characters and the amazing artwork of 12: Summer/What’s on Featuring twenty-three life-like robotic his principal illustrator, Sir Quentin dinosaurs including the giganotosaurus, Blake. It will encourage reading on a the utahraptor and the brachiosaurus, the giant scale and will feature themes such exhibition will aim to highlight the threat as invention, mischief and friendship as of extinction faced by species at the zoo explored in Roald Dahl’s books. such as the Eastern black rhino, Sumatran The Big Friendly Read will encourage Hello! orangutan and Sumatran tigers. children to expand their own reading by And make sure you also visit their exploring similar themes across the Happy days! It’s nearly holiday time, we’ve caught sight of the sun once or Islands Zone, -

Manchester City Centre Welcome! Manchester’S Compact City Centre Contains Lots to Do in a Small Space

Manchester City Centre Welcome! Manchester’s compact city centre To help, we’ve colour coded the city. Explore and enjoy! Central Retail District Featuring the biggest names in fashion, including high street favourites. Petersfield Manchester Central Convention Complex, The Bridgewater Hall contains lots to do in a small space. and Great Northern. Northern Quarter Manchester’s creative, urban Chinatown heart with independent fashion Made up of oriental businesses stores, record shops and cafés. including Chinese, Thai, Japanese and Korean restaurants. Piccadilly The main gateway into Manchester, with Piccadilly train station and Piccadilly Gardens. The Gay Village Unique atmosphere with Castlefield restaurants, bars and clubs The place to escape from the around vibrant Canal Street. hustle and bustle of city life with waterside pubs and bars. Spinningfields A newly developed quarter combining retail, leisure, business and public spaces. Oxford Road Home to the city’s two universities and a host of cultural attractions. approx. 20 & 10 minutes by Metrolink from Victoria Mersey Ferry docking point Amazing Graze Lunch 3 courses for Early Evening Dining 6pm – 7pm Monday to Friday inclusive £13.50 2 courses for * 3 courses for * £16.95 Find us on facebook £9.95£ on presentation of this voucher 240 STORES PleaseP 9 fill in your details below: le . 30 EATERIES as 95 £24.00 e OVER 60 FASHION RETAILERS Name:Na fill o m in n 16 HEALTH e: yo p ur r & BEAUTY BOUTIQUES Email:E det e ma a s manchesterarndale.com ils e il: be n ABodeAB Hotels and Michael Caines Restaurants neverlo shareta your data with third parties. -

BE PART of Lt

BE PART OF lT. soapworks.co.uk 2 A PLACE TO MAKE YOUR OWN. soapworks.co.uk JOlN AN EXClTlNG COMMUNlTY WlTHlN AN AWARD WlNNlNG OFFlCE BUlLDlNG, BRlDGlNG MANCHESTER ClTY CENTRE AND MEDlA ClTY. Soapworks is one of the North West’s most iconic commercial regeneration projects. The scheme transformed the former Colgate Palmolive Factory into a modern and dynamic centre for business, creativity and leisure, providing over 400,000 sq ft of stylish Grade A offices with a BREEAM rating of ‘Excellent’ and EPC rating of B within Salford Quays’ new Media City boundary. AN AWARD WlNNlNG SCHEME 3 soapworks.co.uk 4 soapworks.co.uk COMMUNlTY AT THE HEART. BE A PART OF SOAPWORKS AND GAlN ACCESS TO A RANGE OF COMMUNlTY ACTlVlTlES. From fitness classes to street-food, Soapworks activates the 5 communal spaces and generates a sense of community like no other. Join us and take full advantage of our on-site marketing and events team’s efforts. Seemlessley blending your working days with our well being activities which includes yoga and HIIT classes, as well as our placemaking pop-up events & food vendors that change with the seasons. soapworks.co.uk Raising money for local causes On-site cafe 6 Community activities Pop-up florist Local running routes 12 month calendar of events soapworks.co.uk 24 hour manned reception Shower rooms & lockers Amazon lockers 7 ON-SlTE AMENlTlES • 24 hour manned reception • 24 hour security • Secure cycle storage • Cash machine • Showers and lockers • Pocket park • On-site cafe • Car valet service • On site management team • Visitor -

Manchester-Visitor-Info-V.01.19.Pdf

Manchester Visitor Information What to see and do in Manchester Manchester is a city waiting to be discovered There is more to Manchester than meets the eye; it’s a city just waiting to be discovered. From superb shopping areas and exciting nightlife to a vibrant history and contrasting vistas, Manchester really has everything. It is a modern city that is Throw into the mix an dynamic, welcoming and impressive range of galleries energetic with stunning and museums (the majority architecture, fascinating of which offer free entry) and museums, award winning visitors are guaranteed to be attractions and a burgeoning stimulated and invigorated. restaurant and bar scene. Manchester has a compact Manchester is a hot-bed of and accessible city centre. cultural activity. From the All areas are within walking thriving and dominant music distance, but if you want scene which gave birth to to save energy, hop onto sons as diverse as Oasis and the Metrolink tram or jump the Halle Orchestra; to one of aboard the free Mettroshuttle the many world class festivals bus. and the rich sporting heritage. We hope you have a wonderful visit. Manchester History Manchester has a unique history and heritage from its early beginnings as the Roman Fort of ‘Mamucium’ [meaning breast-shape hill], to today’s reinvented vibrant and cosmopolitan city. Known as ‘King Cotton’ or ‘Cottonopolis’ during the 19th century, Manchester played a unique part in changing the world for future generations. The cotton and textile industry turned Manchester into the powerhouse of the Industrial Revolution. Leaders of commerce, science and technology, like John Dalton and Richard Arkwright, helped create a vibrant and thriving economy. -

Bfi Film Audience Network Unleashes Gothic: the Dark Heart of Film Across the Uk

BFI FILM AUDIENCE NETWORK UNLEASHES GOTHIC: THE DARK HEART OF FILM ACROSS THE UK London, 9th October 2013. Fear stalks the land. Prepare for an unprecedented GOTHIC assault on the senses across the UK, as the BFI Film Audience Network (BFI FAN) launches with a celebration of GOTHIC the hideous and alluring dark heart of film (October 2013 – February 2014), part of the biggest BFI blockbuster project ever. Witches, vampires, werewolves and spectres will be unleashed upon film audiences across the British Isles as Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and all the English regions work together as part of this new and dynamic film network to capture the imagination of the British public. BFI FAN will enable film fans across the nation - who cannot easily access a broader variety of films - to experience a diverse range of activity, through screenings, education, community projects and archive events. GOTHIC is just the start of a whole range of other extraordinary film experiences BFI FAN will bring to local audiences. Thrilling GOTHIC highlights in every part of the UK include: Wales Goes Dark: Abertoir Horror Film Festival: UK premiere of Welsh film The Darkest Day, Aberystwyth (19 Oct), plus Abertoir partnering on festivals at Theatr Clwyd Cymru, Gwyn Hall, The Torch Milford Haven and more to be added Cardiff: Darkened Rooms: Dracula screens at Cardiff Castle (29 Oct - SOLD OUT), (5 Nov - NOW ON SALE) Newport: Night of the Demon at Tredegar House, Newport (30 Oct) Leeds: Gothic Film Festival classic Gothic screenings and events in the beautiful ruins of Kirkstall Abbey for Hallowe’en weekend (31 Oct – 3 Nov) Belfast: Burn Baby, Burn! Witchcraft on film season at the Queen’s Film Theatre (1 – 5 Nov) London: The Dia de Los Muertos (Day of the Dead) Experience! brings classic Mexican horror films, live music and immersive theatre to the Rich Mix (1 & 2 Nov); Hereford: The Elephant Man: A Freakish History in the Black Lion Pub’s attic with introduction and post-film discussion led by Gothic horror expert, Prof. -

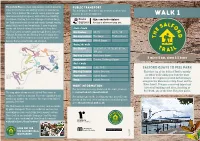

Walk 1 in Between

The Salford Trail is a new, long distance walk of about 50 public transport miles/80 kilometres and entirely within the boundaries The new way to find direct bus services to where you of the City of Salford. The route is varied, going through want to go is Route Explorer. rural areas and green spaces, with a little road walking walk 1 in between. Starting from the cityscape of Salford Quays, tfgm.com/route-explorer the Trail passes beside rivers and canals, through country Access it wherever you are. parks, fields, woods and moss lands. It uses footpaths, tracks and disused railway lines known as ‘loop lines’. Start of walk The Trail circles around to pass through Kersal, Agecroft, Bus Number 53, 79 24, 71, 73 Walkden, Boothstown and Worsley before heading off to Bus stop location The Quays Trafford Road Chat Moss. The Trail returns to Salford Quays from the historic Barton swing bridge and aqueduct. Tram/metro Salford Quays Blackleach During the walk Country Park Bus Number 10, 27, 67, 71, 73, 92, 93, 97, 98, 5 3 Clifton Country Park 100, 101 4 Walkden Roe Green Bus stop location Blackfriars Street Kersal Victoria, Exchange Square 5 miles/8 km, about 2.5 hours 2 Vale Tram/metro 6 Worsley 7 End of walk Eccles Chat 1 Moss 8 Bus Number 8, 26, 34-37 Barton salford quays to peel park Swing Salford 9 Bridge Quays Bus stop location Salford Crescent This first leg of the Salford Trail is mainly Little an urban walk taking you from the most Woolden 10 Tram/metro Salford Quays Moss modern development around Salford Quays Train Salford Crescent Irlam alongside the Manchester Ship Canal and the River Irwell. -

Media Village on Waterfront Quay Provides Over 120,000 Sq Ft of Commercial Space in the Centre of Salford Quays

FLEXIBLE WATERSIDE OFFICES TO LETWATERFRONT QUAY, SALFORD QUAYS MEDIAVILLAGE WATERFRONT QUAY, SALFORD QUAYS ENTER WWW.MEDIAVILLAGE-SALFORDQUAYS.COMWATERFRONT QUAY, SALFORD QUAYS FLEXIBLE WATERSIDE OFFICES TO LET MEDIAVILLAGE WATERFRONT QUAY, SALFORD QUAYS WWW.MEDIAVILLAGE-SALFORDQUAYS.COM WATERFRONT QUAY, SALFORD QUAYS Surrounded by water on three sides Media Village on Waterfront Quay provides over 120,000 sq ft of commercial space in the centre of Salford Quays. At the forefront of the regeneration of Salford Quays over the last 25 years, Media Village now offers a range of opportunities for occupiers seeking flexible and cost effective solutions to their occupational needs. Existing occupiers include Guardian Media Group, Future Electronics and Computer Centre (UK). AT THE HEART OF THE ACTION, IN AND AROUND MEDIA CITY MEDIA VILLAGE MEDIA VILLAGE THE QUAYS DESCRIPTION MASTERPLAN LASER HOUSE MAGNETIC HOUSE LOCATION AMENITIES CONTACT FLEXIBLE WATERSIDE OFFICES TO LET MEDIAVILLAGE WATERFRONT QUAY, SALFORD QUAYS WWW.MEDIAVILLAGE-SALFORDQUAYS.COM WATERFRONT QUAY, SALFORD QUAYS Salford Quays comprises approximately 280 acres of former docklands which was comprehensively cleared in the early 80’s to make way for one of the UK’s most successful urban regeneration projects – Salford Quays. MediaCity:UK M602 Motorway Following the BBC’s decision to relocate to MediaCityUK the Regent Road Roundabout whole of Salford Quays has been re-designated by Salford City Imperial War Museum Council as ‘Media City’. The Designer Outlet Mall ITV and SIS have followed BBC into MediaCityUK which has The Lowry Quay House created a media power house for the area and is acting as a Premier Inn Holiday Inn catalyst for attracting further high profile occupiers. -

Salford City Archive Service

GB0129 N/CC2 Salford City Archive Service This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 21671 The National Archives 21SEP87 Irlams o' th' Height Congregational Church Salford Archives Centre 658/662 Liverpool Road Irlam Salford M44 5AD Reference no: N/CC2 CITY OF SALFORD CULTURAL SERVICES DEPARTMENT Archives catalogue N/CC2 Records of Irlams-o1 -th1 -Height Congregational Church, Claremont Road, Irlams-oU-thT -Height, 1903.-57* n.d. Deposited; H. Carrington, Esq., 6 Hallwood Avenue, Salford, 116 8W, lay pastor, per the Principal Keeper of Social History and Antiquities, Ordsall Hall Museum, April, 1976. Catalogued; A.H. Cross, June, 1976 (revised May, 1978). Locations Archives Centre, 658/662 Liverpool Road, Irlam, Manchester, MJO 5 AD. A banner (references H118-1976) of this Church has been deposited in Ordsall Hall Museum. The Committee minute book beginning in 1904 (N/CC2/C01/AM1) indicates that the Committee had been, in existence before that date. Early pages in this minute book refer to an application to the Lancashire Congregational Union to be accepted as an aided station and also to a decision to hold the service for ithe opening of the Church on 10 January, I9O6. ADMINISTRATION IT/CC2/AM1 Minutes of church meetings, with register of 1906-14 attendance at end for years 1913-14 (1 vol.) /AI-I2 Minutes of church meetings, 1914-20, with register 1914-22, of attendance at end for years 1914-16 and part 1937? n.d. of 1917 (1 vol. containing loose papers, incl.